(source)

(source)

|

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

(9 Apr 1806 - 15 Sep 1859)

English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who was one of the great Victorian engineers. His works includes tunnels, steam ships, railways and bridges.

|

From the National Gazette [of Philadelphia]

in the The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette (9-10 May 1838)

A Journal

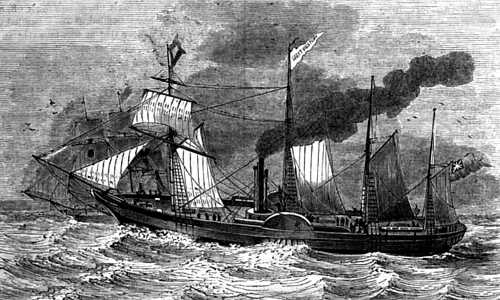

Of the First Voyage of the Steam-ship Great Western, Lieut. James Hosken, R.N., Commander, from Bristol to New York, April, 1838— By a Passenger.

Saturday, April 7.

Our departure from Bristol was at the appointed time of sailing. Having got on board a small steamer, a twaddling little thing, we left the foot of the Cumberland, or outer basin, at a few minutes past 2 p.m., to join the Great Western, at the mouth of the river, the Avon—not Shakespeare’s—a tributary to the Severn, and upon which, at some ten or twelve miles from its confluence with the parent stream, Bristol is situated.

The day was an unpropitious one. A strong breeze, almost a gale, blew dead against us; the clouds lowered, and a cutting rain alternated with a fitful sunshine. Had our lot been cut in those good old times, when Nature, in her freaks, revealed to grandames the mysteries of butter-milk and unhatched eggs, we had surely deemed it ominous, for the elements seemed to fret and fume over the commencement of the voyage. Thanks to the darkness of the latter days, however, the wind to us was but wind, and the rain but rain; so wrapping our cloaks still closer about us to exclude both, our duckling of a steamer was permitted to paddle on.

The scenery in the vicinity of Bristol is, perhaps, the finest of its character in England, and passing down the Avon it is seen in some of its most enchanting features. For some miles below the city the shore, on either side, is a continuity of stupendous granite rock, sometimes attaining the height of three hundred feet above the water mark. Starting from the stream, with but a narrow road or towpath at the base, occasionally to relieve the abruptness, they rise, piling mass on mass and vein on vein, frowning in naked crags, the impracticable precipice—or yielding their severity, gently recede, grudging their rude cliffs to the mountain larch.

At one point on the river, the heights of Clifton were visible, with their graceful crescents peering above like the creations of a fairy land. Near to these we passed the site of the contemplated suspension bridge over the Avon. The workmen are as yet engaged only on the abutments,—enormous structures, wrought upon the hill side, resembling rather the gigantic efforts of a giant race (the engrafting of rock on rock) than the work of common men. An iron bar, seven hundred and eighty-five feet in length, stretched from summit to summit on either side, at an elevation of one hundred and seventy-two feet from low-water mark, shews the precise spot, height, and length, of the intended bridge.

At another point our attention was attracted by men procuring a particular sort of stone. It was at a little distance from the river, but at one of the most precipitous and highest points of rock. They seemed to use nothing but crowbars in the work, the part to which their attention was given being soft. They stood upon small cliffs almost at the top of the precipice, with ropes around their waists and passed over the summit, to assist them in ascending and descending, as well as to guard against any unhappy slips, and prying the stone from its bed, it came down in huge masses, rattling and rebounding as it struck with the noise almost of distant thunder.

Beyond this rocky section the shore breaks into finely sloped hills, abounding in wood, hedge, and lawn. Foliage had not yet burst; still had the plough and harrow been busy, contrasting delightfully the warm and mellow earth with the verdure of the award, already in the rich hue of spring.

The rise and fal1 of the tide in the Severn is thirty feet, and having the flood against us, our passage was prolonged.

We reached the Great Western at about 5 p.m., and strange it seemed. So strongly had curiosity been excited by this vessel, that we, who had now come to take our departure by her, were obliged to wait whilst a small steamer, thronged with eager visitants, left her side to make room for us.

We joined her; and as is ever the case on ship-board, at the appointed moment of sailing, everything was pell mell. It seems little short of professional, or in conformity with some quirk in a sailor’s creed, that it should be so; and had not experience given me a hint of this fact, I would really have been dismayed; spars, boards, boxes, barrels, sails, cordage, seemingly without number, stirred well together; coals for the groundwork, baggage to infinity, captain scolding, mate bawling, men growling, and passengers in the midst of all, in the way of everything and everybody, is a pretty good description of the state of a ship’s deck generally, when about to get under weigh.

It happens mostly that a very little time is sufficient to put matters in tolerable order, and off they go, relying upon the sea to do the rest, in shaking persons as well as things into their proper places. With us, however, the derangement was a little beyond this, and the breeze being now increased to a gale, it was determined by Capt. Hosken to lie by until the morning; so each installing himself in his little castle, found enough to do in the arrangement of it to amuse him for the evening, and all, I believe, found an early bed made welcome by a day of fatigue.

Sunday, 8th.

At 8 a.m., this morning, our ears were saluted by the low roar of the furnaces, which announced the kindling of the fires, the note of preparation for departure.

At 9, the steam was up; our colours were hoisted, the British ensign at our gaff, while that of our sister country, the land of our present hope, was assigned an honourable place at the fore. The call for all hands was immediately made, with the order to man the windlass. It was over two hours before the anchor was to the bow, a delay at which all grew impatient, but unavoidable, by reason of the great scope of chain out, and everything being new, the windlass worked stiffly.

At 12 we were fairly off, and whatever misgivings might previously have assailed us in the contemplation of our voyage, I believe that at this moment there was not a faltering heart amongst us. Such stability, such power, such provision against every probable or barely possible contingency, and such order presented itself everywhere on board, as was sufficient to allay all fear. That there should latterly have been a doubt as to the practicability and safety of a passage by steam across the Atlantic, seems indeed strange, when, with any effort of reason, we look at the question. The North Sea and the Mediterranean, by the way of Gibraltar from England, have been long navigated by steam; and it is now nearly two years since the passage to India, by way of the Cape of Good Hope, has been successfully made by four or five different vessels; and in all this there has surely been as much encountered as is ever likely to assail a navigation by the same means between Europe and America. Yet, that doubts have existed on the score of this new attempt, extensively, and in the minds of many who ought to be able to form a correct judgment upon the subject, there can be no question. It is a weakness of our nature that sometimes so strangely permits our imaginations to beset us with difficulties, which exist only in the fact that an effort to confront them has not been made. Thus it was in a former age that regions unexplored were invested with fancied terrors, and more than half the globe lay for centuries unknown.

The evening found us at the mouth of the Bristol Channel, Lundy bearing N., making our way against a head wind, and upon an ugly hard sea.

Monday, 9th.

The morning opened upon us delightfully, and with such a face as made our steamer glorious—sunny and quiet, the sea heaved in glassy volumes, disturbed only immediately around us by the plunge of our paddle wheels, and the rapid progress of the vessel. To one accustomed to the associations of the sea, as they are usually presented to the voyager a sailing vessel, the effect was very striking. In his feelings, the waves and the expanse of water have, in some measure, taken the places of friends and a stirring world; and their ripplings and splashings are to him like the voices and glee of boon companions, or their tossings and foamings, as the angry discord of other elements; and the absence of these, the quietude of a calm—the glare of the unruffled ocean, conveys to his feelings a sense of solitude and silence not less powerful, perhaps, than would the wilderness itself to one accustomed only to the jarrings and jostlings of the every day world. This, indeed, is the only solitude the sailor knows; the only silence he truly feels; and to see the repose of the deep thus invaded, our vessel coursing on, I can scarce call it aught else, for her swiftness appeared the eagerness of hot pursuit, seemed strange as the sight of some startling apparition of active life in the midst of the unbroken desert.

At 10 a.m. a light breeze from the Northward; made sail; several vessels in sight.

At 12, noon, we came up with and spoke American ship Neponset, of Boston, 4 days out of Liverpool, for Charleston.

At 5 p.m. wind ahead; in all sail; thick fog and a heavy head swell; weather looking dirty.

Longitude, 7° 32’ W.

Barometer, 30 10

Thermometer, 55

Course by Compass, W. by N.

Wind, W. S. W.

Tuesday, 10th.

Fairly shaking hands with old Neptune, through a head wind, and over a head sea. The incipient symptoms of yesterday have become confirmed cases this morning. Sea sickness stalks in stifling horror among us, and the dreadful cry of “steward”—“steward”—the last ejaculation of despair, comes from a dozen nooks, hurried in a piercing treble, or growled forth with muttered maledictions on the dilatory bucket bearer, in the deep tones of thorough bass.

At 9 a.m., two sail in sight—a large ship abeam, to windward, standing E., a ship on the weather-bow, close hauled on the larboard tack; wind W.S.W. Soon discovered a black ball painted in the fore-topsail of the latter, by which we knew her for a packet-ship; hoisted our colours, the American at the fore; kept the steamer up a point, and at 11 passed and spoke her—the South America, 7 days out of Liverpool, for New York.

Whatever might have been the kindness and good will with which we graced our greeting of this fellow wayfarer of the deep, and however warmly and sincerely we would have yielded to any claim upon our charities in his behalf, yet I much fear that, with it all, we entertained at heart a feeling that partook of unbecoming exultation. It was impossible almost that it could be otherwise, and the frailty can hardly be called unpardonable.

The meeting of the packet ship, a creature I may call it of proud pre-eminence, was a sort of contest, and triumph was at that moment in our hands. The feelings of the sailor are ever enlisted for his own ship, whatever she may be; yet sailing, quick sailing, being the beauty—the point of pride—the one thing needful to constitute her perfect, whenever that is found, especially if combined with other merits, she is supremely the object of his regard above all else that he may meet. Her conquests are his, and he would be little less affected by anything impairing her high claims, than if he himself had become the victim of disaster and defeat.

Our salutations were in the courtesy of the seas; our colours were answered by his numbers, to which we again responded by hoisting ours. Thus decked with flags we bore up to speak him. As we approached, the steamer stretched to windward, though not near enough to hail; our engines were stopped, the ship shot ahead, and gathering our way again we passed under his stern and up to leeward. It was a noble sight; and she was under top-gallant sails, making the best of a fair wind, dead ahead, jammed upon a wind, a sailor would term it, and I really know no phrase of more polished form by which to convey the idea better, even to a landsman.

Fancy her careering to the breeze, plunging at one moment, the foam rolling in volumes from beneath her bows—rising at the next—up—up—her polished copper bare, her keel almost out, seeming the very exertion of instinctive effort, then down with a plunge, dashing off the foam again, every inch of canvas stretched to its uttermost, and the wind seeming in her very teeth—fancy this, and you have some notion of a ship at sea “close hauled.” Her sides were crowded with passengers; there were but two ladies. We too bore “a cottage,” with its flaunting veil, and our pride dilated in the display of such a sharer in the venture of our voyage.

Our captains exchanged a mystic tone; the indefinable bellow of a “hail!” “where from?” and “how long out?” were soon asked; adieus were made; and exchanging three hearty cheers, first given by our friends, the steamer urged her way ahead, the helm was ordered hard a-starboard, our colours were hauled down, and we were again upon our course.

At 3 P. M. a ship to leeward, by the wind, on the larboard tack. At 4 P. M. wind hauled to S. W.; made sail. Day ends with fine breeze and smooth sea.

Longitude 12° 17' W.

Distance by log 213 miles.

Barometer 30 20

Thermometer 58

Course by Compass W. by N.

Wind S. W.

Wednesday, 11th.

This morning we were surprised by the appearance of a bouquet on one of our cabin tables; hyacinths, daffodils, violets, and primroses at sea! It were vain to inquire whence they came, so we scout the question, and, like good heathens, receive them, rendering thanks to the Nereides.

It would be difficult for the uninitiated to conceive how ardently every circumstance on shipboard is taken hold of, however trifling it may be in itself, that can in any way be made to contribute to agreeable occupation, or even to a momentary pastime.—The mind seems unwillingly to partake of the restraint upon our corporeal freedom, and to shrink instinctively from its accustomed flights to others of a narrower range: a sail in the distance, a wearied land bird flitting by, an excursion in the boat, a gun let off, a burning barrel turned adrift, the veriest jest that can be named, trifles that at another time and in another mood, would scarce cast the shadow of a gnat upon one’s brain, are there made the objects of delighted interest. They are sought with the zeal of hungry childhood, and if by chance the incident, as in the present instance, assume a familiar feature of domestic life, a household seeming, it is seized with the quick avidity and enjoyed with the zest of a stolen pleasure.

At 6, a.m., passed a large ship showing French colors, standing to the Eastward.

At 8, a.m., a brig standing to the Westward; wind hauling to the Northward, jibed and set square foresail and foretopsail.

At 11, a.m., an American ship to leeward, standing E.

The days ends with a free breeze from N. E.; all sail set, a large swell out of W.S. W.

Longitude, 17° 10' W.

Distance by log, 206 miles.

Barometer, 30 80.

Thermometer, 62.

Course by Compass, W. N. W.

Wind W. S. W. to N.E.

Thursday, 12th.

The repose of last night might be compared to a tossing in a blanket, and a dance of pothooks and frying-pans were nothing in din to the glorious clatter among the moveables that accompanied it; to a sailor it would be quite enough to say, the wind was “ right aft,” the text to a whole chapter of horrors. The motion of a ship under sail has sometimes been compared to the noble bearing of a stately horse; it is a pretty simile, and a vastly exciting one, when upon a smooth sea we can fancy our nag ambles well; or even in a breeze, when mounting the waves with a “side wind,” the exhilaration of the moment may persuade us that we prance upon the deep; but with the wind abaft, the roll, the interminable, ceaseless roll, is beyond the power of imagination to liken to anything to which Providence ever gave a gait. The congregated infirmities of all the halt in Christendom could scarce be worse.

The difference of motion by a “side wind” and the wind abaft is, that with the former, however the ship may pitch, she is still so much inclined always—pressed over by the wind, that whatever moves is sure to go to the lower side, or “down to leeward,” and will there lie quietly. But when before the wind the ship rolls, descending to equal points on either side, and the consequence is, that everything not absolutely spiked or lashed down hard and fast, plays at every oscillation to the utmost of its tether, accompanying the movement with its own peculiar music of creak, clatter, or squeak, as the case may be. Sometimes, as if by way of climax, the water tumbles in over one gunwale, swashing over the deck, and dribbling by every aperture into the cabin below—then rolling again, as if to court the embraces of a sister wave, the ship descends, and again it pours a briny sweep one over the other. Sitting or standing at such a time is equally an exertion of our best powers of tenacity, and to take to one’s berth may be likened to seeking refuge within the arms of a “ demented sentry box.” And with all this, the confusion, the row among chairs, trunks, and all the locomotive paraphernalia of the cabins, the never-dying conflict of platters, spoons, and dishes in the steward’s room, the creaking of bulkheads, and the occasional thump and rumble of a “fetch away” on deck, form an aggregate of ludicrous discomfiture, unequalled by the most refined misery which any derangement or disorder on shore could possibly inflict. I speak now of what sometimes occurs at sea. We have not had anything quite of this order.

At noon thick weather and a moderate breeze at E.

At 8 p.m. wind hauled to N. N. E.; set fore and aft foresail, mainsail and mizzen, sea smooth and the ship was literally flying through the water.

Longitude 22° 51' W.

Distance by log 231 miles.

Barometer 30 80.

Thermometer 63.

Course by compass W. N. W.

Wind E. S. E. to N. N. E.

Friday, 13th.

A fine morning; the sea in its richest livery, a brilliant blue, studded with flowing “white caps,” and looking gay and merry. The day has been interesting by experiments upon our engines; the object was, to ascertain the speed of the vessel relatively with the degree of power applied and the required consumption of coal.

The result is reducible to figures in a very small compass.

| Power of Steam to the square inch. |

Revolutions per minute. |

Miles per Hour. |

Cwt of Coals per Hour. |

| 3½ lbs. or full steam | 15½ | 12¾ | 28 |

| 8-10ths of 3½ lbs. | 15 | 12½ | 27 |

| 7-10ths ditto | 14 | 12¼ | 26 |

| 5-10ths ditto | 13 | 11 | 23 |

The power of the engines being 225 horses each.*

The gradations were arrived at by the “Cramm,” a part of the engine adapted to “cut off the stroke,” as it is technically termed, to any desired proportion, which is done by its action on one of the principal valves in such a manner as partially to close it. The proof of the amount of pressure was shown by an instrument called the “Indicator,” which was screwed upon the cylinder—communicating with it from within for the purpose, and which, by the action of the engine, most ingeniously given to it, described with a lead pencil upon paper, a parallelogram, cutting off one corner, showing the precise vacuum in the cylinder, and by this the proportion of power applied.

To a novice, the whole process seemed a mystic operation, and reminded one of the story of an Indian, who seeing a steam engine, fancied that a spirit lay imprisoned within the boilers, and that by building a fire beneath them, it was excited to fury, and thus put the whole in motion.

The paper and lead pencil in such hands, and the close observation of the besmutted engineers, might verily be said in our case to bear some resemblance to the intercourse of imps with an incarcerated devil.

The experiments strikingly illustrate the mechanical principle of the differences between the ratio of power applied, and that of its results. Our sails were set during the day, with the wind from the southward, but so light as could have had no appreciable influence on our experiments.

The morning was thus well nigh consumed, and a day thus began at sea, to and fro on deck—upon the wing as it might be—is seldom given in the end to sedentary occupations, or to any pursuit more profitable than a prolonged lounge. Our strolls for the afternoon lay between the jib-boom end and the poop, watching the heaving of the sea and the motion of the vessel; and we were at least exhilarated, if made none the wiser by our perigrinations.

The day ends with fine weather; the wind at E. in all fore and-aft sail.

Longitude, 28° 27' W.

Distance by log, 218 miles.

Thermometer, 64.

Course by compass, W. N. W.

Wind, S. E. to N. E.

Saturday, 14th.

The bouquet has our care. It is now among the first duties of the morning to look to it—to cull its withered leaves and replenish the water. It has become a matter of ambition with us to carry into New York a flower still fresh, though plucked in England.—How incongruous it seems that a simple violet should become the testimony to a great achievement!—even to beard the philosopher himself.†

Saturday afternoon on board ship is made to bear some likeness to a termination of the same day on shore by a likeness in its duties—a general clearing up and marked preparation for Sunday. We have had enough of it. Forgetting all else in the bustle, I will merely mention that our decks were “holy stoned!” Hast ever seen or heard of holy stones? They are of the good old family of grindstones, bearing a relationship to it, kindred to that of squeaking pigs to their grandmother. To describe them:—they are blocks of stone, something larger, and nearly as heavy, as a square of 56 pounds weight. They have brush handles attached, and are used with as much sand as may be needful to aid the operation and bring the music to a certain pitch, to scour the decks. Now imagine a dozen or more of these put in motion over head, some two or three feet above you, for the purpose and in the manner I have named—that is, “holy stoning simply,”—infliction in the first degree, and suited to an age ere the inquisition became an exquisite. But the moment chosen invariably happens to be that at which you have just fallen into an afternoon nap, or are enjoying the raptures of delicious morning dreams! and this—but I cannot find a name for the foul torture.

The day being smooth, the engines were stopped at noon, for the first time on the passage, to examine the paddle-wheels, and to “ screw up.” Lay by two hours.

At 2 p.m. proceeded. At 3 came up with and passed a small brig steering W. The day throughout his been fine, with a light breeze from the southward, and smooth sea. All sail set.

Longitude, 34° 9' W.

Distance by log, 218 miles.

Barometer, 30 60.

Thermometer, 62.

Course by compass, W.N.W.

Wind, S. E.

Sunday, 15th.

Commenced with a fine breeze from he southward and a smooth sea—a brilliant morning. All sail set, our ship going nobly on. Nowhere is the influence of fine weather upon the spirits more strongly felt than at sea—a bright day, a fair wind, and the sea glittering in the sun, seem spells which charm every element of happiness within us into activity and life. This seems strange in the absence of so much generally associated with our pleasures, yet it is so; and the reason, I take to lie is this,—that though deprived of much that under other circumstances might minister to feelings of a grosser birth, yet the freedom from care, and the abstraction from the world which every one feels [at sea], leaves us the more susceptible to a subtle influence and a high enjoyment.

Sunday on board ship is mostly as marked and as perceptible by every external characteristic as it is on shore. Swept decks, clean clothes, smooth chins and no work among the crew, are as distinct from the everyday complexion of a sea life, as are closed shops, smart dresses, and a quiet air, from the week day bustle of a crowded city:—and with these, even the sun at sea has the same Sunday look he seems to wear when smiling upon the Sabbath of one’s home. At 11, a.m., we had service in the upper cabin.—Prayers read by the Captain. At 1, p.m., exchanged signals with a large American ship standing E. Day ends with a fine breeze from S. W. and an increasing sea.

Longitude, 39° 40' W.

Distance by log, 241 miles.

Barometer, 30 40.

Thermometer, 65.

Course by compass, W. by N.

Wind. S. E. to S. W.

Monday, 16th

Morning comes and evening goes at sea, as elsewhere, and every day has its chronicle. A ship is a little empire; it has its monarch and its chief counsellors, its patricians and plebeians, its codes and customs, its laws and their vindication, its fashions and its follies; and the history of a voyage might be compared to the annals of an era in the existence of one of those greater members of the world’s community. There is this difference, that while men remain sufficiently unchanged at sea, to carry still the seeds of discord and disunion within, it is left to a nobler influence from without, than that of a fear of our fellow men—a dread of the elements themselves, to overcome them; an influence, that in its character of an appellant to our fears, one is almost ready to believe involves the only principles of combination—the only impulse to a common purpose, to which our imperfect natures are susceptible. A member of our State, of the plebeian order, was this morning given over to the chief judge, and by the chief judge to the king! In plain truth, Jack had been refractory, and refusing his work he was brought to judgment. The hearing was a short one; a negotiation was entered upon with the belligerent, and terms offered for his ratification, either to do duty and share the privileges and protection extended to faithful subjects, or to do nothing and share nothing appertaining to those things which men are pleased to deem wholesome and comfortable—meat and drink. Jack was too much a man of the world to desire to place himself in a position so peculiar as the latter would have entailed, so accepting the former, the affair was ended.

At 6 a.m. the wind chopped into N. W., with a strong breeze, handed a sails; a heavy swell out of S. W.

At noon wind more moderate and hauling to the northward, set reefed fore-and-aft foresail and mainsail.

At 9 p.m. wind hauled to S. W. blowing hard; made the ship snug under reefed fore and aft fore-sail on the larboard tack.

At 11 p.m. wind backed to N. W. in a hard squall and increasing, with a high cross sea running, in all sail, a foul night.

Longitude, 45° 34' W.

Distance by log, 243 miles.

Barometer, 30 30.

Thermometer, 52.

Course by Compass, W. N. W.

Wind, S. W. to N. W.

Tuesday, 17th.

An appropriate figure-head for our ship would be, Vulcan with Neptune by the beard, and old Æolus fairly under foot. Such had been the picture had Ovid told the story of our voyage, for it seems little short of a conquest of the elements.

The past night and day have afforded us, in some measure, an opportunity of testing the powers of steam against the adverse influences of weather, a gale in our teeth, and a sea ahead, which in volume is seldom found in any part of the Atlantic beyond the limits of the banks of Newfoundland. Our ship behaved nobly. She plunged and rolled, as every vessel in similar circumstances must have done—often burying her paddlewheels to the shaft, and was as uncomfortable as any huge cradle well tossed and tumbled could be; yet her motions were easy, and her progress without intermission.

In consequence of the heavy sea, the working of the engines was reduced to ten revolutions per minute, during which time it is shown, by the result of the observations of the morning, that we made an average of five and a half knots per hour.

The morning found our cabin in some confusion, as is usual on ship-board after a rough night. Among other mishaps, the little pitcher holding our bouquet had “fetched way,” and the flowers lay bruised and strewed about the carpet. Our drowsy senses, after a wakeful night, seemed little affected by the event—an undisturbed nap, and an absence of care for our own proper equilibrium on a smoother sea, will doubtless leave us more alive to our loss.

At 5, a.m., passed a brig lying to under close reefed main top sail and balance reefed try-sail.

At 11. a.m., on the eastern edge of the banks of Newfoundland. Exchanged signals with a large barque showing English colors, steering to the southward.

At noon, wind more moderate.

At 6, p.m., stopped the engines, and hove to for a cast of the lead—had bottom at twenty five fathoms.

Longitude, 49° 21' W.

Distance by log, 185 miles.

Barometer, 30 30.

Thermometer, 42.

Course by compass, W. N. W.

Wind, N.W.

[Concluded in next day’s newspaper, dated May 10, 1838]

Wednesday, 18th.

It is quite clear we have no fraternity with the fishes. The porpoise, the most frequent of our ocean visitors usually, whose gambols around the bows are often the subject of a moment’s interest to the voyager, comes now, dashing forward with its merry troop in all their accustomed glee, until near our paddle-wheels they turn—startled by the splashing—and dash off, tumbling and rolling, it would seem, upon each other in their haste, like a bevy of frighted children who had become suddenly assured of having mistaken a hobgoblin for a well-known friend. In making a voyage in the Great Western, every day affords occasion for the expression of astonishment at the progress of science and the attainment of human power; and as vain or as common-place as the question may appear, it seems to present itself there, invested with something like solemnity—when and at what point shall the pile be shaken which constitutes the sublime fabric of human knowledge? But a few generations since, and the ocean upon which we sail, the continent to which our course is directed—aye, more than half the world, were beyond the ken of men! and now—what are they?—what is man himself, and what are human means, wrought out by the divinity within us, compared with the creature and his aids of those days? The question, where will these things find an end? is irresistible.

At 5, p.m., smooth sea and moderate breeze from S. W.

At 6, p.m., a large ship to leeward, steering E.

Longitude, 52° 30' W.

Distance by log, 169 miles.

Barometer, 30 20.

Thermometer, 42.

Course, W.

Wind, W.

Thursday, 19th.

To an accustomed sailor—a minion of the winds—it is long before the novelty of a steamer at sea, with all the attendant circumstances of its internal economy, can wear itself into familiarity. Chiefly he feels a strange relief in the absence of care about the weather or the winds—sources to which he has habitually looked for a large proportion of his contentment. The never ceasing question of the morning to which he is used—“how is the wind?” or, “ how does she head?” presents itself at his waking like the remembrance of some nauseous morning dose now discontinued; and in place of the excitement among his fellow voyagers by a fair wind and the prospect of a fine run, or the despondency by a foul one, and all sorts of evil forebodings, he hears the common parlance of everyday life, or, issuing from his room, finds them distributed in groups awaiting breakfast, in the discussion of the merits of their favourite picture! The space, too, and, as far as regards the Great Western, the splendor around, continually surprise him. The light spars, light sails, and light rigging on deck, look like light walls and great windows to an accustomed prison—robbing it of half its terrors. A sailor, to whom a dark cloud has ever been a thing of watchful apprehension,—like a stealing, crafty enemy—cannot cast his eyes aloft but, feeling a new sense of safety, he will turn to the squall with a grin. and looking it in the face, bid it “ blow his heart out.”

The richness below the cabin seems the expression of individual taste, and the elegance of a bountiful hospitality, rather than a provision for the common participation of the wayfarer; and this at sea, too! The change is a pleasant one, and to the old voyager, unfamiliar as it may be, it is perhaps the more delightful, as he alone can truly estimate the change—a transition from the endurances to what may be called the luxuries of the enjoyments of a sea life.

At 4 p.m., came up with and spoke to the American ship, Jefferson, of Baltimore, 35 days out of London for New York.

At 10, P M, fresh breeze from S. W., and much sea.

Longitude, 56° 48' W.

Distance by log, 206 miles.

Barometer, 30 10.

Thermometer, 63.

Course by Compass, W.

Wind, S. W.

Friday, 20th.

A thoroughly uncomfortable day, and decidedly a bad road; with such tracks left us to crawl over as the wind god makes when there has been heavy work. Our coach rolling and pitching abominably, to the very hubbs. A more than usually heavy sea has left us little with which to occupy ourselves today, beyond the care needful to maintain that position that is the pride of our nature, well-poised equilibrium on both legs. The motion of the ship was greater this morning than we had before had. Nearly calm, or the little [wind] then was nearly ahead, our sails were of no service, and a heavy sea, such as usually follows a violent gale, tossed us like a floating bird upon the waves. It was satisfactory, however, as affording further illustrations of the capabilities of the vessel.—Her engines were eased, yet she continued at a speed of not less than six or seven knots per hour. And those features in her model which before sailing, were the only grounds of doubt, as far is mere model was concerned—her length and sharpness—seemed now the characteristics best adapted to her purpose. She cleaves the sea upon her water-line, while her bearings below are quite sufficient to give her buoyancy almost without a plunge; and a remarkable consequence of this, aided by her length, is, that her way, though abated, as must ever occur to any vessel upon a head sea, is yet never wholly lost; hence have we been during her whole voyage without that jar and check, by the stroke of the sea, to which vessels are usually subject under similar circumstances. The nature of the propelling power has, also, an important agency m this distinction:— the action of the paddle-wheel being from the centre of the vessel horizontally, has no effect upon her perpendicular motions, while that of the mast under a heavy press of sail, being from above, acts partially as a lever upon the hull, to make every plunge the more severe.

There is another remarkable distinction in the Great Western—an absence, in a great measure, of sensible motion or jar, from her engines. This arises as well from the strength of the vessel as from the character of the engines themselves,—a verv low pressure, a short-stroke and a slow movement.

Towards the evening the sea became more smooth, the wind hauling to the northward. Sudden transitions of this kind, more than once upon our voyage, have led us to the idea that the power of locomotion gives us an advantage never before dreamt of; that we are enabled in some measure to verify the Munchausen story of keeping the rain at our horse’s tail—that, in short, we may very much decrease the endurance of foul weather by running out of it. It would, at all events, be an interesting subject of inquiry, by a comparison of log, from time to time, with the account of other vessels, to ascertain how far the changes arising from this circumstance really do occur.

Longitude, 50° 34' W

Distance by log, 183 miles.

Barometer, 30 deg.

Thermometer, 55.

Course by Compass, W. by N.

Wind, S. W. by S.

Saturday, 21st.

We have to congratulate ourselves upon another fine morning and another smooth sea. With a fine breeze from the northward, we are staggering under all our canvas, and the engines in full play, it is impossible to conceive any anything of human sway or human power upon the deep more exhilarating or delightful. Few positions in life carry with them a greater spell upon the feelings, or excite us to a nobler sense of our own nature, than that of the voyager upon the ocean, when his ship, bending under a press of canvas, and mounting majestically at every succeeding wave, she urges her rapid way. Such magnitude, such power, and yet so child-like! A word—the slightest movement of the helm—and she is governed; the winds and the very sea seems to be at her commander’s control.

With us, too, there is much to aid the excitement; we are of the first(‡) to make the great adventure, to establish that success which may, and probably will, mark an era in the intercourse—in the fraternity of a wide world.

The afternoon was diversified by a sharp [snow] squall. It continued until our masts, sails, and rigging were completely hung in its fleecy drapery, and until the snow lay nearly two inches deep upon our decks; the result of which was, a thorough set-to at snowballs by all the idlers of the cabin.

The declining sun seemed to announce our approach to the shores of America. Without that diversified richness of the sky which sometimes awaits upon the day’s departure there, it yet had enough of characteristic to proclaim it as its own.

A mass, of heavy clouds had gathered above and around, darkening the day. It broke in the west, and rose in a broad, low, and strongly-defined arch, like the lifting of a curtain, displaying the setting sun through an atmosphere so rich and so pure that the fancy might almost deem it such as angels dwell in. The ocean lay tinted in its hues, blending the gold and purple with its own deep blue; and as the sun sank still lower, streams of light shot upward, bathing the heavens and the whole canopy of clouds in floods of richest crimson.—It was a sunset and twilight of the new world.

Saturday evening on board ship is mostly a time of some distinction, and this being the last we looked for on our voyage, both dinner-time and evening were made merry; at the former the health of our captain was drunk for the tenth time on the passage, I believe, and responded to with that enthusiasm which warm hearts own, when feeling points to an object worthy their high regard.

The evening had its own sweet toast of sweethearts and wives—and more than this: but this, to all the rest was as the key note to the overture.

Day ends with a fine breeze from the northward, all sail set, close hauled.

Longitude, 64° 24' W.

Distance by log, 192 miles.

Barometer, 30 30.

Thermometer, 42.

Course by compass, W.

Wind, N. W.

Sunday, 22nd.—The day has partaken something of the excitement of anticipated arrival.—The anchors were got over the bows, the cables were got up and bent, and all those arrangements made which mark the approach to land; and, as is ever the case among the idlers, the disposition to do little else than lounge and talk and dream of the things of the morrow, prevailed over every other incentive to occupation.

At 5 a.m., spoke packet ship Westminster, forty eight hours out of New York, for London.

At 8 a.m. a sail to windward, close hauled, on the starboard tack.

At 10 a.m., a sail to leward. Day ends with a moderate breeze from N. W. and a smooth sea. All sail set, close hauled.

Longitude, 69° 3' W.

Distance by log, 198 miles.

Barometer, 29.90.

Thermometer, 34.

Course by compass, W. by N.

Wind, N. W. by N.

Monday, 23rd.

The morning of arrival to the journalist is one of brief periods. Objects multiply upon his attention too fast;—the occasion itself distracts him. The number of vessels within the horizon, the bustle of active preparation, the momentary expectation of making the land, and the dimly-descried pilot-boat in the distance, are excitements too great to admit of that equanimity which is needful to prolonged remark. One almost breathes hurriedly at the thought of all that flits before him in the delightful picture of gratified curiosity, or of home, and friends, and fire-side enjoyments which his imagination paints as so nearly within his reach.

To pursue our narrative—we have a morning such as in every way we could have desireded, bright and tranquil;—the enjoyment of it is in happy keeping with our recollections of the whole voyage.

At 10, a.m., we were joined by the pilot. His boat—a graceful little schooner, came down before a fine breeze, and hauling up to windward, salutations were exchanged, his skiff was launched, and a few moments brought him to our deck. It was amusing to observe the wonderment of the tenants of the little craft at our vessel. If eyes and mouths be any indices to feeling, there must have been something not often of this earth in theirs.

At 12, noon, the cry of land ran through the ship; and in an instant there was a rush to the poop, the rigging, the forecastle, the highest point of the vessel—it was there—[ahead,] and “land, O!” was reechoed loudly and merrily upon every tongue. It is difficult—impossible, justly to describe the expressions which pervade a ship at the moment of first discovering land. It is a look of joy—not the expression of a common passion, but a highly-wrought sense,—an eruption of the feelings which displays itself in all that tongue can utter, all that smiles can say, all that eye can speak. It is a tune as well of grave ejaculation as of merry jest. “My country!” cried one, extending his arms half solemnly, and with a look of thought. “And there,” cried another, peeping through his nether eye, and pointing to the broad sheet of foam which marked our way upon the water, as far as eye could reach—“there is the road to mine.”

There is something, too, of the ludicrous with all at such a time. The resurrection of “other” clothes, and the exchange of hats for caps, make such changes as seem almost to claim the necessity of other introductions. The rusty jacket has suddenly become the superfine black long-tailed, and the out-at-elbows of yesterday, sports now perhaps the finest fleece in the flock.

Our progress was rapid, and the land which at first was but a dark line on the horizon’s verge—a cloud seemingly at its early birth—soon became distinctly visible—the heights of Neversink.

Before crossing the bar, our “poles,” which had been some time “housed,” were all aloft, and flags streaming at each; the British ensign at the gaff. That at the fore was one adopted at the launching of the ship—a combination of the British and American ensigns, the stars quartered on the British union, the stripes on the field— an emblem one might fancy of that regard for each other, if one may so speak of States, of that alliance in a noble fellowship of parent with its daughter empire which it is quite certain the intelligence of both countries ratifies, and would desire should ever be.

At one moment it seemed probable we should be afforded the opportunity of adding an act of kindness to the events of the day. The wind light and baffling. A little schooner at some distance, in attempting to pass too near the edge of a shoal, was so drifted by a strong tide, that her grounding amidst the breakers seemed to us inevitable; and it was only after the most positive assurances of the pilot that she would work clear, that our captain would allow the steamer to proceed further, without first sending her a hawser, and relieving her from the difficulty.

At 3, p.m., we passed the Narrows, opening the bay and harbor of New York, our sails all furled, and the engines at their topmast speed. The city was scarcely discernible—reposing, it seemed, in the distance in the quietude of majesty, while little islands on either hand, cannon crested, stood like nature’s ushers to this Queen of the Western World. The country around looked arid and unsightly, the vegetation of spring having not yet put forward.

As we proceeded, an exciting scene awaited us. Coming abreast of Bradlow’s Island, we were saluted by the fort with twenty-six guns, and the coincidence of this with our own movements on board, heightened our enjoyment of it immeasurably. The sky-lights to our cabin abaft are made to form two tables on deck, mahogany topped, and with a most bewitching look of invitation to a repast upon them, whenever a smooth sea and sunny day make it pleasant to dine or lunch beneath the awning.

It had been agreed amongst us some days previously, that before we left the ship, one of these tables should be christened the Victoria, the other President. Wine and fruit had been set upon them for this purpose—we were standing round the former of them—the health of Briton’s Queen had been proposed—the toast was drunk,—and amidst the cheers that followed, the arm was just raised to consummate the naming, when the fort opened its fire.

The effect was electric. Our colors were lowered in acknowledgment of the compliment, and the burst which accompanied it from our decks—drinking to the President and the country, and breaking wine again, was more loud and more joyous, than if at that moment we had unitedly overcome a common enemy. Proceeding still, the city became more distinct—vessels, masts, buildings, spires seeming taller as we approached—trees, streets—the people:—the announcement of the arrival of the ship by telegraph had brought thousands to every point of view upon the water side,—boats, too, in shoals were out to welcome her, and every object seemed a superadded impulse to our feelings. The first to which our attention was now given was the Sirius, lying at anchor in the North River, gay with flowing streamers, and literally crammed with spectators—her decks, her paddle boxes, her rigging, mast-head high! We passed around her, receiving and giving three hearty cheers, then toned towards the Battery. Here myriads seemed collected; boats had gathered around us in countless confusion, flags were flying, guns were firing, and cheering again—the shore, the boats, on all hands around, loudly and gloriously, seemed as though they would never hare done.

It was an exciting moment—a moment which in the tame events of life find few parallels; it seemed the outpouring congratulations of a whole people, when swelling hearts were open to receive and to return them. It was a moment, that if both nations could have witnessed, would have assured them, though babblers may rail, and fools may affect contempt, that at heart there is still a feeling and an affinity between them. It was a moment of achievement!—we had been sharers in the chances of a noble effort, and each one of us felt the pride of participation in the success of it, and this was the crowning instant; [experiment then ceased—] certainty was attained; our voyage was accomplished.

† Dr. Lardner in his work on the steam engine, 1836, declares the project—the enterprise, one of the boldest in the application of steam power—the then contemplated intercourse between London and New York by steam, to be impracticable.

‡ Note by the Editor. This is an error; and our author's remarks and congratulations on the priority of the Great Western in navigating the Atlantic by steam, are without foundation. To Americans belong the honor of being the first to show the safety of Steam Navigation across the Atlantic.The following notice of the voyage is from the “New York Courier and Enquirer” of the 26th ultimo.

“THE FIRST STEAM-SHIP ACROSS THE ATLANTIC.—Without wishing in any manner to derogate from the honour that belongs to Lieut. Roberts of the ‘Sirius’ steam-ship, just arrived from Cork, it is due to our country to state, that to America belongs the credit of having first accomplished a steam voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. This took place in the year 1819, which is therefore 18 years since. The ‘Savannah’ built here in New York by Francis Fickett; owned by Daniel Dodd; Stephen Vail, of Speedwell, near Morristown, built the engine of the ship: Captain Rogers was her commander, and she sailed to Europe twice. She visited Liverpool and Stockholm; the King of Sweden, Berniadotte, was on board of her, and presented Captain Rogers, with a stone and muller (now in the possession of Mr. George Vail), as a token of his gratification at the success of the enterprise. The ship also visited Petersburgh, and Capt. Rogers received from the Emperor a present of a silver tea-kettle, as a token of his gratification at the first attempt to cross the Atlantic by steam. The ‘Savannah’ afterwards went to Constantinople, and the captain received presents from the Grand Seignor.”

[Note by Webmaster—The writer is identified as “Mr. Foster, a highly talented Gentleman, of Philadelphia.” when reprinted in The Logs of the First Voyage, Made With the Unceasing Aid of Steam, Between England and America, by the Great Western of Bristol (1838), Appendix IV, 63-72. The Editor’s footnote above is the longer version appearing in this book, on pages 69-70. The newspaper report also was reprinted in the British periodical, Chronicles of the Sea (16 Jun 1838), 217-224 with a few paragraphs omitted, and slight differences (mostly punctuation) from the newspaper article. Where the Chronicle had occasional additional words making the sense clearer, those were added into the text above within brackets. The Chronicle also gave “six or eight miles” in place of the “ten or twelve miles” in the opening paragraph. Footnotes from different columns of the original two newspaper articles have been gathered at the end of the text as shown above.

Having read the above historic event, to put it on a timeline in your mind, consider that the American Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. An 18-year-old in that year, might have lived to age 80, and could have possibly travelled on that transatlantic steam-ship in 1838. From the narrative above, it is clear that the British and American nations were on good terms. Another significant date is the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, still 23 years ahead in time from the year the Great Western sailed. Slavery was still accepted practice in the Southern States. Below is a news items item totally unrelated to science. It was the article in the newspaper column adjacent to the featured story above. It is a shocking contrast to the social harmony on the Great Western. It is not at all about science, but it is an important reality check to put on the timeline. Which is why Webmaster includes it below.]

From the Saint Louis Republican, of April 30.

(As reprinted in The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette (9 May 1838)

A HORRIBLE ENFORCEMENT OF

THE LYNCH LAW.

The particulars of the drowning of a free negro man, named Tom Culvert, second cook of the steam boat Pawnee, on her passage up from New Orleans to this place, are as near the facts as we have been able to gather them. On Friday night, about 10 o’clock, a deaf and dumb German girl was found in the store room with Tom. The door was locked, and at first Tom denied she was there: the girl’s father came, Tom unlocked the door, and the girl was found secreted behind a barrel. Tom was accused of having used violence to the girl, but how she came there did not clearly appear. The captain was not informed of this during the night. The next morning some four or five of the deck passengers spoke to tho captain about it; this was about breakfast time. He heard their statements and informed them that the negro should be safely kept until they reached St. Louis—when the matter should be examined and if guilty, should be punished by law.

Here the matter seemed to end, the captain after breakfast returned on deck, passed the cook’s room and returned to his own room; immediately after he left the deck, a number of the deck passengers rushed upon the negro, bound his arms behind bis back and carried him forward to the bow of the boat. A voice cried out “throw him overboard,” and was responded to from every quarter of the deck—and in an instant he was plunged into the river. The captain hearing the noise, rushed out in time to see the negro float by. The engine was stopped immediately. This occurred opposite the town of Liberty. Several men on shore seeing the negro thrown overboard, pushed from shore in a yawl and arrived nearly in reaching distance of the negro as he sunk for the last time. The whole scene of tying and throwing him overboard scarcely occupied ten minutes, and was so precipitate that the officers were unable to interfere in time to save him.

Several of those engaged were identified, the captain placed a strict watch over the boat and determined to have them arrested on his arrival here.—Some of them, however, succeeded in effecting their escape. One who is accused was arrested here, and is lodged in jail for further examination. Since the death of the negro it has been ascertained by his confession to another on the boat that he was guilty. There were between two hundred and fifty and three hundred deck passengers on board.

- Science Quotes by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

- 9 Apr - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Brunel's birth.

- The Great Eastern Steamship - from Scientific American (28 Jun 1856).

- Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, by Angus Buchanan. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Isambard Brunel.