(source)

(source)

|

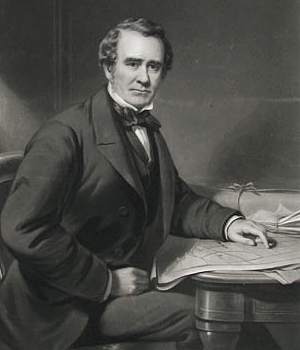

Sir John Hawkshaw

(9 Apr 1811 - 2 Jun 1891)

British civil engineer noted for his work on the Charing Cross and Cannon Street railways among many other projects.

|

Sir John Hawkshaw, F. R. S.

Obituary from Engineering News (1891)

[p.595] The name of Sir John Hawkshaw, the great engineer, who died in London on June 2, is as well known in America as in England, and the following sketch of his life, from a somewhat fuller biography in Engineering, will be interesting to American engineers:

John Hawkshaw was born in 1811, in Leeds, and was educated at the grammar school of that town. At an early age he entered the office of Mr. Charles Fowler, a celebrated road maker; but preferring railways to highways, he was soon removed to the office of Mr. Alexander Nimmo, who was at the time engaged upon a scheme for a railway between Manchester, Leeds and the Humber. Mr. Nimmo died in 1831, and some of his clients sent young Mr. Hawkshaw to manage some Bolivian copper mines, and he remained in South America for three years.

Upon his return to England he published a book entitled “Reminiscences of South America, from Two and a Half Years’ Residence in Venezuela.” He then became an assistant to the late Mr. James Walker, and married, in 1835, the daughter of the Rev. James Jackson, of Green Hammerton, Yorkshire. At the age of 26 he was appointed Engineer to the Manchester & Bolton Canal & Ry., which later was a part of the extensive Lancashire and Yorkshire system, of which he eventually had charge.

About this time he was consulted by the directors of the Great Western Ry. as to the desirability of maintaining and extending the broad-gage system, then only in operation between London and Maidenhead. His report, elaborately defending the narrow gage as the most economical, first made known his great ability and brought him into prominence as an engineer, though Brunel’s genius carried the day with many large shareholders.

In 1840 Mr. Hawkshaw succeeded Mr. George Stephenson, when that gentleman retired from active service, as engineer of the Manchester & Leeds Ry. He eventually developed this system until it covered 428 miles. He worked a steep incline at Halifax, with grades of 1 in 44, with ordinary locomotives ; and by so doing broke down the prevailing prejudice against steep grades, and made railways possible in regions before considered inaccessible by rail.

Work flows in rapidly to the successful engineer, as the following list of a few of the undertakings about which Mr. Hawkshaw was consulted will show: The Riga & Dunaberg and the Dunaberg & Witepsk railways, in Russia; the Penarth Dock and dock in Cardiff Roads; Londonderry Bridge, Ireland; Charing Cross and Cannon St. bridges and stations, with the connecting line; the East London Ry.; the Government railways in Mauritius; the Albert Docks, Hull; the south dock of the East and West India Docks; the foundations of the forts at Spithead; the ship canal from Amsterdam to the North Sea. Mr. Hawkshaw was also for many years consulting engineer to the Madras Ry. and the Eastern Bengal Ry.; he was also referee to the San Paulo Ry., in Brazil.

Among other undertakings not mentioned was the completion of Holyhead Harbor, after the death of Mr. Rendel in 1866. This was a work of national importance, and on its formal opening the honor of knighthood was conferred on the engineer in 1873. Another government enterprise intrusted to Mr. Hawkshaw was the examination of the various schemes for the supply of Dublin with water. This was in 1880; the Vartry scheme which he recommended was carried out. In 1862, very shortly after the bursting of the St. German’s sluice of the Middle Level, Mr. Hawkshaw was called in to advise upon and carry out the best means for excluding the sea from the large tract of low-lying land then inundated. He replaced the sluice by 16 large siphons and thus averted all danger of a repetition of the former catastrophe. In 1863 Mr. Hawkshaw contested Andover, but failing he never again sought Parliamentary honors.

In 1862 Mr. Hawkshaw went to Egypt as consulting engineer to report on the works of the Suez Canal. He had no difficulty in deciding that it did not present any insuperable engineering difficulties, a conclusion that would not be acceptable to Lord Palmerston. On a second visit he surveyed the Nile between the first and second cataract, and proposed works to render it navigable as far as Wady Haifa. From there he advocated a railway to Khartoum. In 1865 he became, in conjunction with Mr. J. Dirks, engineer to the Amsterdam Sea Canal, a direct navigable channel, 15½ miles long, from Amsterdam to the North Sea, intended to supersede the North Holland Canal of 52 miles long. The canal has a depth of 23 ft., with a clear width at the top of 197 ft. But the Severn Tunnel will rank as Sir John Hawkshaw’s greatest engineering feat, in view both of the commercial importance of the work and of the physical obstacles which were overcome. During the thirteen years when the tunnel was under construction, the influx of water was so constant and copious that fears were frequently entertained as to the possibility of completing the work. But Sir J. Hawkshaw’s skill and perseverance placed the issue beyond doubt even before 1885, when the first train passed under the river between England and Wales. Before he commenced this work he had already proposed the boring of a tunnel between England and France, and had made a number of borings and soundings, partly at his own expense. His opinion was entirely favorable to the scheme; there are, however, other considerations than those of an engineering nature to prevent its execution.

Mr. Hawkshaw was elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers on February 16, 1836. On August 7, 1838, he became a member, and in 1862-63 he filled the presidential chair. November 3, 1880, he was made an Honorary Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and of the Royal Society, and a Knight Commander of the Brazilian Order of The Rose. In 1875 he was the President of the British Association, which that year met in Bristol.

Mr. Hawkshaw early established a high reputation as a Parliamentary witness. The care and precision with which his evidence was always given, and the fact that both from high conscientiousness of character and great powers of memory he was never found to contradict himself, no matter after what interval of time, gave to his testimony great weight and value. For some years past he had relaxed his professional exertions, and on December 31, 1888, he definitely retired, leaving his business to the care of his son, Mr. John Clarke Hawkshaw, and to his partner, Mr. Harrison Hayter.

- 9 Apr - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Hawkshaw's birth.