THE SIEGE OF THE SOUTH POLE.

The Story of Antarctic ExplorationExcerpt from Chapter XX: Early Expeditions of the Twentieth Century

by Hugh Robert Mill (1905)

|

|

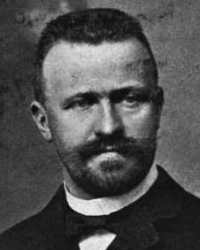

| [cropped from plate facing

p.418] Professor Dr. von Drygalski Photograph by Messrs Thomson, London Click to enlarge |

[p.421] Although there were no naval officers or men in the party the Gauss was privileged to sail under the Imperial ensign. She left Kiel on August 11th, 1901, and made a slow voyage to Cape Town, carrying out much valuable oceanographical work on the way. It was not until December 7th that the expedition left the Cape and, calling at Possession Islands in the Crozets, by the way, anchored in Royal Sound, Kerguelen Land, on the 31st. Rabbits, descended from ancestors which came over with the Challenger, came hopping down to the beach to welcome the strangers of whom they had no fear, and the small party of German scientific men which had been landed some months previously by a steamer chartered in Australia were found completing their observatory. The Gauss remained for a month and then, after calling at Heard Island, she steered south-eastward to investigate the region about 90º E., between Knox Land, the most westerly reported with any confidence by Wilkes, and Kemp Land. The parallel of 60° S. was crossed on February 12th, 1902, in 92° E., and icebergs were met with in considerable numbers. On the 14th a sounding was obtained in 1730 fathoms within 60 miles of the position assigned by Wilkes to Termination Land, but a close pack made it necessary to change the course to southwest, and for two days progress was very slow, and no land was seen. On the 19th soundings were suddenly struck in only 132 fathoms and the sea was clear of ice, except large bergs drifting before a strong southeasterly wind.

|

|

| [reduced from plate facing

p.420] The "Gauss" Under Sail Photograph supplied by Professor E. von Drygalski Click to enlarge |

Before winter set in a band of emperor penguins appeared, floundering clumsily over the ice to examine the strange creatures who had invaded their domain. Other sledging parties went out and crossed the floe in various directions to the land, just entering the Antarctic region proper which the Gauss, sealed in the floe north of the circle, never penetrated. The winter was passed in diligent [p.423]observations of all the phenomena that could be studied. The days were short, but the party were on the sunward side of the circle, and there was no week-long darkness to contend with. The weather however was very bad; tempestuous winds raged for a week at a time, whirling the copious snowfall in fierce blizzards, and often threatening to tear the ship to pieces, though the sea-ice was never cracked or even thrown into dangerous pressure-ridges.

When spring came sledge-journeys were resumed, but they were not for exploration so much as for research, and the results have an importance which cannot be stated at once. No bare land was seen except the solitary nunatak of the Gaussberg, and when summer came all thoughts turned to the freeing of the ship. The ice was from 15 to 20 feet thick, and blasting made no impression on it. A deep trough was melted in the ice to the depth of six feet or more by the heat of the sun beating down upon the black surface of a path of cinders that had been spread from the ship to the edge of the floe for that purpose, and after many days a storm came which first freed the floe and set it adrift, then cracked it along the sun-wrought line of weakness and the Gauss was free.

Burning the oily bodies of penguins as fuel, the ship began to move on February 8th, 1903. For two months she struggled in the ice, trying to work her way to the westward through the drifting bergs and floes, and at length in longitude 80º E. she gave up the attempt and struck northward into the open sea. Oceanographical work was continued and Cape Town was not reached until June 9th. Drygalski was anxious to spend another season in the Antarctic in order to investigate the conditions between the newly discovered Kaiser Wilhelm II. [p.424] Land and Kemp Land; but an appeal to the authorities at home brought in reply definite instructions to return, and the Gauss anchored in the Elbe on November 24th, 1903. The Kerguelen party had suffered severely on account of an outbreak of beri-beri, one of the scientific observers died in the Isle of Desolation, and the life of another was saved with difficulty. But the expeditions had amply fulfilled their primary object of accumulating collections and observations which it will take many years to work out fully.

From: The Siege of the South Pole: the Story of Antarctic Exploration, by Hugh Robert Mill, publ. A. Rivers, Ltd. (1905) (source: Digitized by Google)

See also:

- Today in Science History event description for birth date of Erich von Drygalski on 9 Feb 1865.

- "The South Polar Expeditions," Monthly Weather Review (1901)

- "The German Antarctic Expedition," by Dr. Erich von Drygalski, The Geographical Journal, Royal Geographical Society, Vol XVIII, No. 3, September 1901, pages 279-282.