(source)

(source)

|

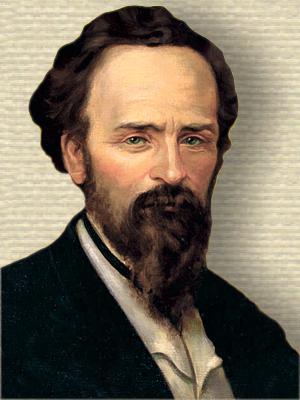

Linus Yale

(4 Apr 1821 - 25 Dec 1868)

American inventor and manufacturer of the cylinder or pin-tumbler lock known by his name, which he patented in 1861. Yale gained an expert reputation as a manufacturer of bank locks.

|

LINUS YALE AND HENRY R. TOWNE

WHO REVOLUTIONIZED LOCK-MAKING

Famous Leaders of Industry (1920)

[p.341] THE now world-famous “Yale” lock had its origin in the village of Newport, Herkimer County, New York, about the year 1840, when Linus Yale, senior, began the manufacture, for the first time, of this new kind of lock. They were described as “pintumbler” locks, and, besides their novelty, were of great mechanical excellence.

Linn Yale, junior, was born in 1821 and became the foremost lock-expert in the country, far surpassing in skill and inventive genius even his well-known father.

The work of the two Yales, father and son, especially that of the latter, has had a profound and lasting influence on the lock industry. Nearly all American lockmakers, and many foreign countries, have adopted the principles of lock construction introduced by them, and have followed their lead in making improvements in design and in methods of production. Linus Yale, senior, resurrected the ancient pin-tumbler of the Egyptians, and adapted it to modern conditions of use, while Linus Yale, junior, by combining it with the small revolving “plug,” made possible the use of a flat key, and by embodying the tumblers and plug in a separate unit, or “cylinder,” reduced the key to a constant length for locks of all kinds, irrespective of the thickness [p.342] of the door on which used. It is difficult to realize today that prior to 1865 practically all keys were round, and had to be long enough to reach through the door into the lock, and that a bunch of keys might weigh pounds where it now weighs only ounces. The work of Linus Yale, junior, included also improvements in the combination, or dial, lock for banks which were fundamentally sound and are now embodied in standard practice, and the metallic front postoffice box, now the accepted standard throughout the world.

Linus, from an early age, gave evidence of mechanical ability. When he was not at the village school or at home poring over his books, he was usually to be found at his father’s small plant, playing with locks and keys, the workmen’s tools, and rummaging in the junk pile.

But the boy, as well as having inventive talent, had artistic tastes and loved to sketch and paint, indoors and out. When he went fishing he would often neglect the fish nibbling at his bait, to make a sketch of a pretty bit of landscape or of a bird or animal.

After he was all through with his schooling, and his father asked him what he was going to be — a painter or a locksmith — he said he thought he’d like to be a painter.

So Linus, junior, began his career as an artist, and for some time diligently worked at his profession, painting portraits and landscapes that bore the impress of true artistic talent.

Before long, however, the young man’s inventive genius began to assert itself, causing him to turn his [p.343] attention more and more to mechanical pursuits. The example of his father, a successful inventor and maker of bank locks, decided him to abandon his art as a means of making a living and devote himself exclusively to lock-making.

He was a young man of high intelligence, and it did not take him long to obtain a mastery of the business. Within a few years after his father’s death, Linus Yale had become the leading bank-lock expert in the United States.

In those days bank-locks were large, very intricate and operated by keys. Mr. Yale, soon after succeeding his father, produced a series of locks of this type that were remarkable for their ingenuity, beautiful workmanship and security. Known as “ Yale Locks,” they were distinguished by such names as “ Infallible,” “Magic,” “Monitor,” etc.

The famous “lock controversy” which arose in England during the World’s Fair of 1851 when the American, Hobbs, succeeded in picking the best English bank locks led to similar contests between American bank-lock makers.

The young locksmith was drawn into the controversy and after first discovering how to pick a famous English bank-lock, discovered also how to pick his own best bank-locks, and ended by demonstrating that any lock having a keyhole could successfully be picked by one having the necessary skill and tools.

This was a somewhat disconcerting discovery for Linus Yale, the bank-lock expert, to make, but it led to revolutionary changes and improvements in [p.344] locks, for from now on he concentrated his attention on the combination, or dial lock, which in crude forms had been known for centuries. To such wonderful perfection did he bring the “combination” lock, that the several types of high-grade bank locks developed by Mr. Yale gave his company world-leadership in the manufacture of bank locks — locks used for bank safes, doors and vaults.

The “ Yale “ lock, now so familiar on the front doors of residences and on office desks, was brought to perfection by Mr. Yale during the period 1860-64, when he brought out an adaptation of the old Egyptian “ tumbler “ lock. Its greater security and conveniently small key gave it great popularity.

The evolution in bank and other locks thus initiated by Linus Yale has been continued and progressively developed to this day, completely revolutionizing the world’s lock industry.

Mr. Yale was of medium height and build, quiet and somewhat reserved in manner with strangers. Those privileged to know him intimately testify to a delightful personality, responsive nature and keen appreciation of the finer aspects of life. His artistic temperament was ever in evidence and his note-books were filled with sketches, alternately of mechanical ideas, of bits of landscapes, and of familiar faces. He loved to fish and knew all the trout streams near his home. Like many inventors or mechanical geniuses, he disliked business and, when he formed his partnership with Mr. Towne, made it plain that he wished to leave the responsibility of business management largely to him.

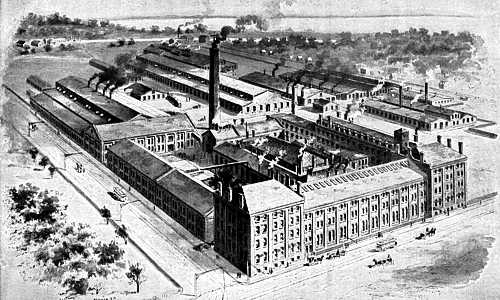

[p.345] This partnership was formed in 1868. In the summer of this year a mutual friend introduced Mr. Towne to the talented and ingenious inventor of locks, Linus Yale, whose business, chiefly in bank locks, then employed only thirty-five men. In October, at Stamford, Conn., was effected the organization, with Mr. Yale as president, now known as The Yale & Towne Manufacturing Co.

Three months later, in December, 1868, Mr. Yale died suddenly and very prematurely, since when the enterprise has been controlled and directed by Mr. Towne. The new firm inherited Linus Yale’s brilliant ideas, ideas which have since revolutionized American practice in lock designing, but which were made commercially practicable only by Mr. Towne’s remarkable business sagacity. Starting with Mr. Yale’s radical departure from the old methods of lock construction, Mr. Towne has greatly amplified these original features and introduced still further radical changes and designs.

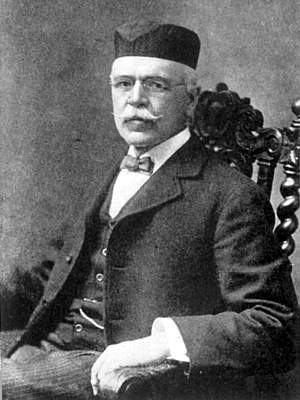

Boys developed rapidly during the great national upheaval of the Civil War, and those equal to great responsibilities found the opportunity to show what kind of stuff they were made of. The rise of Henry R. Towne, Linus Yale’s partner, to high and responsible positions was one of unexampled rapidity.

Henry R. Towne was born in 1844 in Philadelphia, where his father was one of the owners and operators of the Port Richmond Iron Works. Henry was an unusually bright and intelligent boy, and, after his academic studies were completed, he was sent to the [p.346] University of Pennsylvania. The War of Secession, however, interrupted his studies, and, at seventeen, he entered the drafting-room of his father’s iron works. Such rapid progress did he make that in 1863 he was placed in charge of government work in the shops in connection with repairs on the U. S. gunboat Massachusetts.

The Port Richmond Iron Works had meanwhile contracted to furnish the engines for the famous old monitor Monadnock, and in 1864, Henry (not yet twenty) was sent to the Charlestown Navy Yard to assemble and erect them in the ship.

Then he was sent to the Portsmouth Navy Yard in sole charge of erecting and testing the machinery of the monitor Agamenticus (now Terror), and later to the Philadelphia Navy Yard to engine the cruiser Pushmataha.

These were tremendously responsible tasks for a youth, but he did them so extremely well, that, though only twenty-one, he was made acting superintendent in general charge of the shops of the Port Richmond Iron Works, the concern in which his father was a partner.

When peace came young Towne realized the need of further and more exact knowledge in many lines of study which the war had interrupted. So he became a close and industrious student under the guidance and instruction of the late Robert Briggs, C. E., and went with him on an engineering tour of Great Britain, Belgium and France. Before returning he took a special course in physics at the Sorbonne, Paris. In the meantime, [p.346] his father had retired from the manufacturing business.

After returning to the United States, Mr. Towne spent a year in further study and experimental work with Mr. Briggs. During this association he carried on numerous experiments with leather belting, the results of which were accepted as standard for twenty years.

Then, for further education in the designing and use of special machinery, Mr. Towne entered the shop of William Sellers & Co., manufacturers of the Gifford injectors. A year or so later, in 1868, came his meeting with Linus Yale, as related.

Mr. Towne has been the chief factor in the growth and development of the business, and its tremendous expansion in this country and abroad has been due to his unusual combination of mechanical with business ability, his keen foresight and untiring efforts to maintain a product and service of high excellence. He brought to the business the training and practice of a mechanical engineer, together with a natural aptitude for organization and executive management, thus ensuring success.

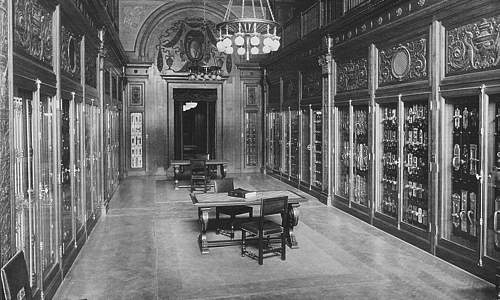

Mr. Towne was one of the pioneers in the improvement of sanitary and other conditions in factories, and to-day the Yale & Towne plant at Stamford, Conn., with its gardens, library, hospital, school, employment bureau, safety devices, etc., is conceded to be one of America’s “model” industrial plants.

During the war the Company, in addition to large quantities of its normal products, such as padlocks, [p.348] chainblocks, etc., also made, for the United States Government, rifle grenades, bomb-dropping devices, fuse-setters, pumps, cavalry bits, buckles, fasteners, etc., and special parts for mines, gas nozzles, etc .

Some interesting statistics, for the year 1916, will give some idea of the bigness of this typical American manufacturing plant. The fifty-eight buildings at that time contained four thousand eight hundred machines and eight thousand three hundred belts; the plant’s consumption in peace time of coal, twenty thousands tons; fuel oil, six hundred thousand gallons; pig iron, two thousand five hundred tons; steel, four thousand three hundred tons; copper, one million six hundred thousand pounds; lumber, one million eight hundred thousand bd. ft., and water one hundred and fifty million gallons.

There are forty-five thousand varieties of products manufactured, and it costs almost $100,000 to print and distribute some fifteen thousand copies of the one thousand-page catalog describing them.

The Works’ hospital treated, during 1916, twenty-nine thousand six hundred and fourteen cases, of which eighteen thousand seven hundred and twenty-seven were surgical.

The plant now covers twenty-five acres and has upwards of five thousand employees. Half a century ago, in 1868, when Linus Yale and Henry R. Towne founded the business, the plant covered a portion of five acres and had thirty-five employees.

The idea of stamping the word Yale in a coined panel on the keys and all other products of this company was [p.349] conceived of by Mr. Towne in 1903, and there are few better-known trademarks.

The company operates another large plant in Canada and has numerous branches abroad.

The guiding principle of the builders of this great business has been honesty of purpose and of endeavor; for, in Mr. Towne’s opinion, “There is no legacy so rich as honesty.”1

- 4 Apr - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Yale's birth.