Recollections of

M. Boucher de Perthes.

Being Some Account of the History of the Discovery of Flint Implements

By Lady Grace Anne Prestwich

From Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, June 1895

[p.

939] M. BOUCHER DE PERTHES was no geologist. He himself,

in one of his

numerous letters to an English friend, disclaimed any right to the

title in these words, “Je

ne suis pas un savant et en

g�ologie moins qu'en autre chose.” Yet his name

is so

inseparably associated with the discovery of flint implements in beds

of geological age, that a few notes of a day spent with him before

these flints were generally accepted and recognised as the handiwork of

man may be of interest, now that their artificial origin is

established, and their significance in being something more than simple

natural objects is understood. Unfortunately, our antiquarian of

Abbeville had given forth his geological theories before he had found

his flint implements. Hence, when his far-sighted perseverance was

rewarded by the discovery of works of primitive man - which he had over

and over again predicted - geologists gave neither heed nor attention

to his announcements, and he had to endure no littlte ridicule and

neglect.

[p.

939] M. BOUCHER DE PERTHES was no geologist. He himself,

in one of his

numerous letters to an English friend, disclaimed any right to the

title in these words, “Je

ne suis pas un savant et en

g�ologie moins qu'en autre chose.” Yet his name

is so

inseparably associated with the discovery of flint implements in beds

of geological age, that a few notes of a day spent with him before

these flints were generally accepted and recognised as the handiwork of

man may be of interest, now that their artificial origin is

established, and their significance in being something more than simple

natural objects is understood. Unfortunately, our antiquarian of

Abbeville had given forth his geological theories before he had found

his flint implements. Hence, when his far-sighted perseverance was

rewarded by the discovery of works of primitive man - which he had over

and over again predicted - geologists gave neither heed nor attention

to his announcements, and he had to endure no littlte ridicule and

neglect.

Jacques Boucher de Cr�vecœur de Perthes was not always known by the name of De Perthes. He was born at Rethel in 1788, and it was not until the 16th September 1818, during the reign of Louis XVIII, that a royal decree authorised him to assume his mother's name of De Perthes, “she being the last descendant of Pierre de Perthes and Marguerite Rom�e, cousin-german of Joan of Arc.” His father held office in the administration of the customs, and at the age of sixteen the young Jacques was enrolled in the same service, and was sent to Marseilles. After a few months there, he resided successively at Genoa, Leghorn, and in several German towns, returning to France in 1811, after having been engaged in missions connected with his service to different countries. For a short time he was sub-director of the Paris customs, and finally in 1825 succeeded his father as director of the Douane at Abbeville, an office which he filled until his retirement from the service in 1853. This post was then cancelled, having only been held by father and son. During nearly thirty-six years he filled the presidential chair of the Soci�t� d'Emulation at Abbeville, the Memoirs of which testify to his unremitting industry and to the wide range of subjects on which he wrote. He was rarely absent from the meetings of this society, except when he traversed Europe to collect the materials which he gave to the world in his many books of travels. His ‘Hommes et Choses’ appeared in four volumes; the ‘Voyage � Constantinople par l'Italie, la Sicile, et la Gr�ce’ came out in two volumes; ‘Voyage en Danemarck, en Su�de, et en Norv�ge,’ as well as ‘Voyage en Espagne et en Alg�rie en 1855,’ ‘Voyage en Russie en 1856’ and also ‘Yoyage en Angleterre, �cosse, et Irlande en 1860,’ besides others, appeared in single volumes. He also published his presidential addresses to the Soci�t� d'Emulation, likewise several discourses to Abbeville workmen, such as “On Probity,” “On Courage, Bravery, &c.,” “On the Education of the Poor,” “On Poverty,” “On Obedience to the Laws,” “On the [p.940] Influence of Charity,” “On innate Ideas, Memory, and Instinct,” and several on questions of political economy.

In many respects M. Boucher de Perthes was a man in advance of his time. Besides his addresses to workmen he was engaged in numerous philanthropic schemes, and he was a warm advocate for the settlement of international quarrels by arbitration, at a time when few Frenchmen held such opinions. His versatile pen was never idle. We know1ittle more of his several tragedies and comedies than their names. No man was ever more possessed by the cacoethes scribendi. There is, in short, scarcely a subject on which he did not touch—from plays, poems, romances, satires, and ballads, on to “Spontaneous Generation” and to that cause c�l�bre, “The Human Jaw of Moulin Quignon.” But he was essentially an archeologist and antiquarian. Thus at the date of our visit to Abbeville, now [1895] nearly seven-and-thirty years ago, M. Boucher de Perthes was known in France as a voluminous author of light literature, but chiefly as a collector and writer on antiquities.

The first work in which he predicted the certainty of traces of industrial remains of primitive man coming to light, was one in five volumes, entitled ‘De la Cr�ation, Essai sur l'Origine et la Progression des �tres,’ which appeared in 1838.

Yet long before that date he had a preconceived idea of the discovery he was about to make, the origin of which is recorded in the first volume of his ‘Antiquit�s Celtiques et Ant�diluviennes’ in 1847:-

“It was on a summer evening at Abbeville, while examining a sandpit at the end of the Faubourg Saint Gilles, that the idea occurred to me that instruments cut out of flint might be found in Tertiary deposits. However, none of those about me exhibited the slightest trace of workmanship. Some were still encrusted, others rubbed and worn round. Here and there a broken one, yet without the least trace of man's labour. This occurred in 1826. Several years passed by, and though I examined several localities, I discovered nothing. At last one day I thought I recognised the work of man on a flint of about 12 centim�tres in length, from which two pieces had been chipped off. I submitted it to the examination of several archaeologists: not one could see in it anything more than a common flint stone, accidentally broken by the workman's pick. In vain I showed that the fracture was very ancient, and that the bed from which it was taken had never before been disturbed. ...

“My convictions remained unshaken. I continued my search, and soon discovered another, similar to the first, and cut in the same manner: with great joy I tore it from the bed in which it lay half-buried. I thought that the attention of my judges would be awakened by the coincidence,—they were not even willing to look at it.

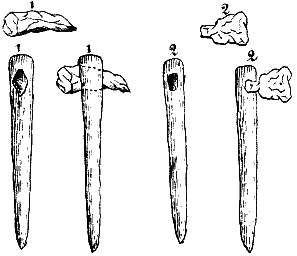

“I discovered a third. In my own opinion this amounted to absolute proof. They did not doubt but that the flint was really taken from an undisturbed bed of diluvium; but as to the workmanship, they discredited it, and concluded that it had been broken like the others by the same cause - that the fractures were all caused in the same manner. I then discovered several implements (haches). Here the evidence of man's workmanship, I thought, should be clear to every one; but still it was only clear to myself. One day a fine axe in flint was brought to me; in this case the workmanship was incontestable, but I had not seen it taken from its bed. The labourers assured me of the fact, and its colour, and the remains of the sand still adhering to it, were sufficient evidence. Yet these incredulous persons insisted that it had not been so taken, and as a reason gave that it could not have come from the diluvium. I then recommended the search for myself” &c.

[p. 941] It will thus be seen that M. de Perthes' anticipations had put him upon the right track, and when in 1832 a trench was being excavated outside the ramparts of Abbeville for the construction of a canal leading from the Hocquet Gate to the Rouen Gate, he was all eagerness to inspect the excavations, and to procure any relics that might be exhumed. Two Celtic haches, with handles of deer-horn were found by the labourers, and though only Neolithic or of comparatively recent date, the discovery of them roused his enthusiasm to the highest pitch.

We

hear of no other extensive excavations until 1837, when works

were resumed for the cutting of trenches for the defence of the place.

It was then that M. Boucher de Perthes suggested that a Commission

should be appointed to watch the excavations, and to secure any

specimens or relics that the workmen might come upon. Many of the

members of the proposed Commission happened to be busy men, others were

absent; their numbers dwindled away until the Commission became

represented by M. Boucher de Perthes alone. He had, however, every

assistance from the engineer officers directing the works, and he made

a point of purchasing any fragments that the workmen might find,

besides offering an extra reward for each specimen of any interest.

We

hear of no other extensive excavations until 1837, when works

were resumed for the cutting of trenches for the defence of the place.

It was then that M. Boucher de Perthes suggested that a Commission

should be appointed to watch the excavations, and to secure any

specimens or relics that the workmen might come upon. Many of the

members of the proposed Commission happened to be busy men, others were

absent; their numbers dwindled away until the Commission became

represented by M. Boucher de Perthes alone. He had, however, every

assistance from the engineer officers directing the works, and he made

a point of purchasing any fragments that the workmen might find,

besides offering an extra reward for each specimen of any interest.

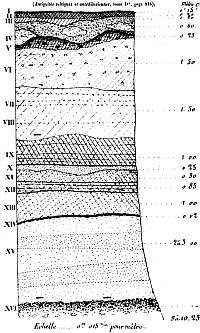

A series of thin beds of shingle or pebbles, alternating with peat, were exposed, and underneath the lowest was one of carbonised wood. Below this last was a sort of open platform made of small joists of oak roughly squared, all unmistakably the work of human hands. There was nothing remarkable in the superposition of these beds, which were distinctly within the human period; but the exposure of them was interesting, and they incited M. de Perthes to undertake all his own account excavations in the older undisturbed gravels of the valley. The cuttings into the shingly beds at the Rouen Gate acted as a spur—if spur were needed; and when the diggings into the older gravels were begun, M. de Perthes was confident that he was on the point of some great discovery. He employed his ample fortune liberally, and when the workmen found the first old flint implement, he promised a reward of double the amount for the next, provided that he could see the specimen in situ.

The first announcement of his discovery of a pal�olithic flint implement in gravels of the age of the Drift was in a work entitled ‘De I'Industrie primitive, ou les Arts et leur origine,’ published in 1846. In a description of the gravels of Menchecourt, he records the occurrence of this worked flint implement, and asserted that it was found among remains or fragments of bones of elephant, rhinoceros, and other extinct animals at the bottom of a bed of gravel underlying many m�tres of modern deposits. The inference was clear. It made it probable that man in this district had been a contemporary of these extinct animals, and M. de Perthes, in recording the fact, announces with enthusiasm that he felt impelled to prosecute his researches with ardour, as he was about to unfold a page of history hitherto unread. In 1842 to 1843, three other flint implements were exhumed from the same locality, thus confirming and corroborating the evidence furnished by the first specimen. As the excavations were carried on further, our antiquarian by degrees amassed more and more of [p. 942] his pi�ces justificatifs, being confident in the hope that some day—maybe some far-off date—in spite of the sneers of an unbelieving public, the facts would ultimately be acknowledged, and would speak for themselves.

In 1849 the first of the three volumes of the 'Antiquit�s Celtiques et Ant�diluviennes' appeared, announcing that numbers of rudely worked flint implements had been met with in the old undisturbed beds of gravel. The two districts which yielded the greatest harvest were were Amiens and Abbeville; the first embraced St Acheul and Moutiers, while the Abbeville district included Menchecourt, St Gilles, and Moulin Quignon. He repeated his assertion that these worked and chipped flints, to which he assigned so high an antiquity, were found at depths varying from 9 to 16 feet, and in association with bones of extinct animals. His announcement was altogether at variance with the preconceived and accepted axioms on the geological age of the human race; he was notorious for having previously propounded theories regarding the antiquity of man without any facts to support them, therefore it was not surprising that when be did hit upon a great discovery, he could not obtain a hearing, and was treated as a wild visionary. One reason of the general unbelief was that the figures in the book are only in outline, and are mostly so badly executed, and include so many that show no sign of work, that they failed to do justice to the specimens. Yet, with a patience which at this far distant date one cannot think of without admiration, he urged his countrymen to put his startling theories to the test, and make excavations for themselves in unbroken ground; but he was only laughed at, and men of science held aloof. Nevertheless, undaunted be worked steadily on, accumulating a large and miscellaneous collection.

In England few men of science had heard mention of his name. Still there was one English geologist who knew of the reported discovery of so-called worked flints, and who had it in view to visit Abbeville at some convenient season, and judge of it for himself. Mr Prestwich was apparently the only one who, from his knowledge of the geology of the Department of the Somme, thought it a fit base for investigation. Other engagements, however, prevented him carrying out this project, and in the meantime his friend, the late Dr Hugh Falconer, who had been engaged with him in the joint investigation of Brixham Cave near Torquay, took the opportunity in passing through Abbevil1e of paying a visit to M. de Perthes, and inspecting his collection, though time did not allow him to visit the localities where the implements had been found. He was so impressed with the statements of M. de Perthes, and with the character of the implements, that he at once wrote to Mr Prestwich and urged him to proceed to Abbeville. With characteristic generosity he invariably assigned the precedence to this friend, saying, “What I did was to stir up the embers of your interest in the matter into a quick flame.”

It is right, however, to mention that in France there was an exception to the general disbelief of the flints having been fashioned by the hands of man—Dr Rigollot of Amiens, who had been very antagonistic to the views of M. de Perthes, but whose opinions underwent a complete change after he had personally examined the ground and the evidence. On his [p.943] return to Amiens he discovered similar flint implements in the great gravel-pits at St Acheul near Amiens, which had been excavated through and below an old Gallo-Romano burying-ground. Dr Rigollot ultimately was so convinced of the facts that be became one of the strongest advocates for their recognition, and his interesting memoir upon 'Instruments en Silex trouv�s � St. Acheul,' published in 1855, was a special pleader on their behalf: but Dr Rigollot was not known as a geologist, and disbelief still prevailed.

Before giving an account of our reception at Abbeville, we

would

fain notice an attractive portrait in our possession. It is the

lithographic likeness of a very handsome man; and as it is dated 1831,

it must have been taken when M. de Perthes was in the prime of life.

There does not seem to be much resemblance between the original as we

knew him and this picture, if we except the large clear straight eyes,

a certain regularity of feature, and an expression of benevolence and

placidity common to both. But we only saw the septuagenarian, whereas

this likeness must have been taken when he was in his forty-third year.

A profusion of curls cluster about the high forehead and temples, and

the drapery, which French artists know so well how to adjust for

pictorial effect, consists of a velvet trimmed cape, thrown back so as

to show the collar of an embroidered uniform, and the orders which are

displayed on his breast. To the end of his days he took pleasure in

presenting this portrait, and this only to his personal friends. He

never would be drawn nor photographed when advanced in years.

Before giving an account of our reception at Abbeville, we

would

fain notice an attractive portrait in our possession. It is the

lithographic likeness of a very handsome man; and as it is dated 1831,

it must have been taken when M. de Perthes was in the prime of life.

There does not seem to be much resemblance between the original as we

knew him and this picture, if we except the large clear straight eyes,

a certain regularity of feature, and an expression of benevolence and

placidity common to both. But we only saw the septuagenarian, whereas

this likeness must have been taken when he was in his forty-third year.

A profusion of curls cluster about the high forehead and temples, and

the drapery, which French artists know so well how to adjust for

pictorial effect, consists of a velvet trimmed cape, thrown back so as

to show the collar of an embroidered uniform, and the orders which are

displayed on his breast. To the end of his days he took pleasure in

presenting this portrait, and this only to his personal friends. He

never would be drawn nor photographed when advanced in years.

It was on a bitterly cold morning on the 1st of November 1858 that

we arrived at Abbeville. We were on our way to Sicily, where Dr

Falconer wished to explore the bone-caves, and other caves on the

shores of the Mediterranean, and the writer had the privilege of

accompanying him as secretary. We were a day behind the date fixed for

an interview with M. de Perthes; therefore, taking the earliest train

from Boulogne, we deposited our luggage at the old “T�te de Bœuf” on

arrival at Abbeville, and hurried on through streets of pointed gables,

where the sun had not had time to melt the crisp frost of the night—on

to the house in the Rue des Minimes. It was a large old building,

which stood back from the street in an iron-railed enclosure; but our

dismay was great to see at a first glance that it was shuttered and

blinded as if untenanted, and only one window by the door was open,

cal�che with luggage standing

as if for a traveller on the point of

departure. Five minutes later, and another hand would have had to

chronicle the first recognition by English men of science of the old

flint implements of the Somme Valley. M. de Perthes had made a point of

coming in from the country for the interview on the previous day, and

thinking that we had passed on our way, he was about to return there.

We were ushered into a small room on the ground-floor, which was crowded with examples of medieval art. There was no flint implement visible: the walls, from ceiling to floor, were covered with old pictures, specimens of bronzes and brasses, beautiful carvings, prominent among them all being a great ebony crucifix. In a few minutes M. de Perthes entered, and gave us an eager welcome. The cal�che had been countermanded, shutters unbarred and [p.344] venetians thrown open,—our arrival, in short, had intercepted the journey. He was just upon seventy, vigorous and active, not at all betraying his years. He looked a men carefully preserved; the thick brown wig was unmistakably a wig, and there was a suspicion—nay, a certainty—of artificial coloring about his complexion. He showed us his private study, which opened off the small outer room, and which was literally crammed with curiosities. The house from garret to ground floor was a great museum, the staircase walls lined with paintings, and room after room devoted to one or other branch of art, principally medieval. His collection of curios was very cosmopolitan, much having been amassed doubtless while on foreign travel. The roomy old house was absolutely filled with relics and treasures of bygone days, with not a single habitable-looking or comfortable room in it, and must have been a dreary abode for any other than its owner.

Finally we were taken to the geological room or gallery, containing the flints which were the object of our journey to Abbeville. The collection was a magnificent one and full of interest, and our host was almost breathless with excitement in detailing the circumstances in which each specimen had been found. The remainder of that memorable day was spent in this gallery, but it nearly finished the unfortunate secretary. The gallery was like an ice-house, there was no fire, and the very handling of the flints was freezing work. So much has been written and published about this collection that I need only allude to it, and will transcribe the letter which Dr Falconer wrote from the “T�te de Bœuf”that same evening.

“My dear Prestwich,—As the weather continued fine, I determined on coming here to see Boucher de Perthes' collection. I advised him of my intention from London, and my note luckily found him in the neighbourhood. He good-naturedly came in to receive me, and I have been richly rewarded. His collection of wrought flint implements, and of the objects of every description associated with them, far exceeds anything I expected to have seen, especially from a single locality. He had made great additions since the publication of his first volume, in the second—which I have now by me. He showed me “flint” hatchets which he had dug up with his own hands mixed indiscriminately with the molars of E. primigenius. I examined and identified plates of the molars—and the flint objects, which were got along with them. Abbeville is an out-of-the-way place, very little visited, and the French savants, who meet him in Paris, laugh at Monsieur de Perthes and his researches. But after devoting the greater part of a day to his vast collection, I am perfectly satisfied that there is a great deal of fair presumptive evidence in favour of many of his speculations regarding the remote antiquity of these industrial objects, and their association with animals now extinct Monsieur Boucher's hotel is from ground-floor to garret a continued museum filled with pictures, medieval art, and Gaulish antiquities, including antediluvian flint knives, fossil bones, &c If during next summer you should happen to be paying a visit to France, let me strongly recommend you to come to Abbeville. You could leave the following morning by an 8 a.m. train to Paris, and I am sure you would be richly rewarded. You are the only English geologist I know of who would go into the subject con amore. I am satisfied that English geologists are much behind the indications of the materials now in existence, relative to this walk of post-glacial geology, and you are the man to bring up the leeway. Boucher de Perthes is a very courteous elderly French gentleman, the head of an old and affluent family,—and if you wrote [p.945] to him beforehand, he would feel your visit a compliment, and treat it as such.

“I saw no flint specimens in his collection so completely whitened through and through as our flint knives—and nothing exactly like the mysterious hatchet which I made up of the two pieces. What I have seen here gives me still greater impulse to persevere in our Brixham exploration. ...” H. Falconer.

The result of this letter was that Mr Prestwich in April 1859 made his first visit to Abbeville, where he was shortly joined by some geological friends whom he had invited to meet him there, and on the 26th of May his paper, entitled ‘On the Occurrence of Flint-implements, associated with Remains of Extinct Mammalia, in Undisturbed Beds of a late Geological Period,’ was read to the Royal Society.1 This paper made a great sensation, demonstrating as it did that a large portion of the flints in M. de Perthes' collection were of human workmanship, and pointing out their undoubted geological position. We shall quote one or two passages from the abstract of this paper:—

2 This only refers to the large worked haches. On his first visit to Menchecourt, the day after his arrival at Abbeville, he was fortunate enough to obtain, in one excavation he had made to a depth of about 20 feet beneath the surface, several fine flint flakes with large bulbs of percussion, in a bed with abundant remains of the mammoth and other extinct mammalia.

3 Subsequently, Mr Prestwich was summoned by a telegram from Paris, to which he responded by going to St Acheul and finding an implement in situ.

“At Abbeville the author was much struck with the extent of M. Boucher de Perthes' collection. There were many forms of flints in which he, however, failed to see traces of design or work, and which he should only consider as accidental; but with regard to those flint-instruments termed 'axes' (haches) by M. de Perthes, he entertains not the slightest doubt of their artificial make. They are of two forms, generally from 4 to 10 inches long, ... and were the work of a people probably unacquainted with the use of metals. ... The author was not fortunate enough to find any specimens himself;2 but from the experience of M. de Perthes, and the evidence of the workmen, as well as from the condition of the specimens themselves, he is fully satisfied of the correctness of that gentleman's opinion, that they there also occur in beds of undisturbed sand and gravel.3

“With regard to the geological age of these beds, the author refers them to those usually designated post-pliocene (Pleistocene), and notices their agreement with many beds of that age in England.”

1. That the flint implements are the work of man

2. That they were found in undisturbed ground.

3. That they are associated with the remains of extinct Mammalia.

4. That the period was a late geological one, and anterior to the

surface assuming its present outline, so far as some of its minor

features are concerned.

“He does not, however, consider that the facts, as they at present stand, of necessity carry back Man in past time more than they bring forward the great extinct Mammals towards our own time, the evidence having reference only to relative and not to absolute time; and he is of opinion that many of the later geological changes may have been sudden, or of shorter duration than generally considered. In fact, from the evidence here exhibited, and from all that he knows regarding drift phenomena [p.946] generally, the author sees no reason against the conclusion that this period of Man and the extinct Mammalia—supposing their cotemporaneity to be proved—was brought to a sudden end by a temporary inundation of the land: on the contrary, he sees much to support such a view on purely geological considerations.”

The effect produced by this paper was very great. Before writing it, Mr Prestwich had been joined by Mr (now Sir John) Evans, and together they had examined the flints and gravels of Amiens and Abbeville. Both being experts in different departments—one from his practical knowledge of geology, especially of the more recent deposits, and the other holding the foremost rank in archaeology—their joint opinion carried great weight. Thus when their belief became public, that M. de Perthes had made an important discovery, and that a large proportion of the flint implements in his collection were what he had claimed them to be, men of science on both sides of the Channel cast away their doubts and unbelief, and the Valley of the Somme became at once the shrine for many a scientific pilgrimage. No longer had M. de Perthes occasion to bewail in bitterness of spirit the roughness of the road of science; his labour of years was recognised, and a sudden revolution effected in his favour. His letters of this date, especially those addressed to Dr Falconer and to Mr Prestwich, are expressive of the most lively satisfaction and gratitude.

In the same year we read of another visit by the latter to this

flint-bearing district, accompanied by Messrs Godwin-Austen, J. W.

Flower, and R. W. Mylne, followed by one from Sir Charles Lyell. Then

again, in 1860, Mr Prestwich led a party of his personal friends there,

including Mr Busk, Captain (Sir Douglas) Galton, and Sir John Lubbock

(Lord Avebury). A host of geologists and others followed on the same

errand, amongst whose names we note those of Sir Roderick Murchison,

Professors Ramsay, Rupert Jones, Henslow, Rogers, and Mr Henry Christy.

That cold November day spent by Hugh Falconer in examining the

collection of flints and stones and bones had had far-reaching results.

Nor did French savants remain longer unconvinced. Mr Prestwich, satisfied by the success of his paper to the Royal Society, addressed a letter to the French Academy of Sciences, urging the significance of M. de Perthes' discoveries. The effect of this communication was that M. Gaudry, a distinguished member of the Institute, visited Abbeville and Amiens to examine the implements and the flint-bearing beds. He found several worked flints in situ, and his researches confirmed M. de Perthes' statements: his report had the effect in Paris that the paper to the Royal Society had in England, and a French pilgrimage to the valley of the Somme began, headed by well-known members of the Institute, among whom were MM. de Quatrefages, Lartet, Hebert, and many others.

Our antiquarian of Abbeville was now a proud and happy man, and if he did see the attacks of one or two adverse critics in England, who stigmatised him as “that amiable fanatic,” he heeded them not: he could afford to smile at such criticisms. One cannot resist giving a quotation from a humorous note of Dr Falconer's. It is dated about a year after that first visit to Abbeville:—

“London, 4th Nov. 1859.

My dear Prestwich,—I have a charming letter from M. Boucher de [p.947] Perthes—full of gratitude to 'Perfide Albion' for helping him to assured immortality, and giving him a lift when his countrymen of the Institute left him in the gutter. He radiates a benignant smile from his lofty pinnacle—on you and me—surprised that the treacherous Leopard should have behaved so well.”

But although M. de Perthes had thus achieved the ambition of his life, and had been spared to see recognised the importance and value of his collection of the works of primitive man, he had again to experience the “stony roughness of the road of science.” In his remarkable collection there was a certain admixture of very carefully worked specimens, in the authenticity of which he himself blindly believed, but which his English friends at once pointed out and unhesitatingly condemned as spurious. There can be little doubt but that certain of the workmen were dishonest; and lured on by the awards held out to them for every implement found, they thought to do business on their own account, and secretly started a manufactory of their own. These modern imitators copied the implements with considerable exactness, declaring to our antiquarian of Abbeville that with their own hands they had dug them out of the gravel. These forgeries were really deceptive in form and make, but experts were not slow to detect the absence of patina or vitreous glaze, that “varnish of antiquity,” and the staining which are characteristic of old palaeolithic implements, and which the workmen had not been able to reproduce.

But the culminating interest in the later years of the life of M. de Perthes was his asserted discovery of a “human jaw” with flint haches in the couche noire of the gravel-pit of Moulin Quignon. The authenticity of this jaw, which he firmly believed to be of the same age as the accepted palaeolithic implements, was generally questioned, in face of his asseveration of having extricated it with his own hands on the 28th of March 1863. During all these years of excavations in the gravels, remains of man himself had been carefully looked for, yet never found, and this was the first occasion on which a human bone had come to light.

This asserted discovery excited the most lively interest on both sides of the Channel. Dr Falconer at first had been inclined to believe in the remote age of the jaw, but the “deliberate scrutiny” of the materials which he had carried away from Abbeville compelled him to alter his opinion. To quote his words:—

To settle the question definitely, it was agreed that a deputation of English savants should proceed to Paris to confer with representatives of their French brethren. This deputation consisted of Drs Falconer and Carpenter, Messrs Prestwich and Busk, all Fellows of the Royal Society; while the French members, who were largely drawn from the ranks of the Institute, were MM. de Quatrefages the eminent naturalist, Desnoyers the. geologist, Edouard Lartet the palaeontologist, and Delesse, professor of geology, with M. Milne-Edwards the zoologist as their president. Other distinguished naturalists joined in the investigation, as, for example, our [p.948] old friend M. Gaudry, M. A. MilneEdwards, and the Abb� Bourgeois. Sir John Evans was prevented by other engagements from joining in at this stage of the inquiry.

Three meetings of the Commission were held in Paris in May 1863, the proceedings being conducted with as great solemnity as if a human life hung in the balance, and depended on their deliberations. And what a remarkable assemblage!

Unable to agree, they adjourned to Abbeville, when the picturesque aspect of the conference had its crowning touch. Here the members were reinforced by the presence of M. de Perthes, with that also of several distinguished savants, such as MM. H�bert, de Vibraye, &c., and the sitting was held at the quaint old “T�te de Bœuf” far into the night. At 2 a.m. they separated, to meet once more a few hours later for the summing up. The proc�s verbaux of each meeting had been voluminous and minute, but the evidence was so perplexing that in the final verdict there was only unanimity on the first clause—namely, “The jaw in question was not fraudulently introduced into the gravel-pit of Moulin Quignon; it had existed previously in the spot where M. Boucher de Perthes found it on the 28th of March 1863.”

It was a bitter disappointment to M. de Perthes that his English friends, in acknowledging the fact of the human jaw having been truly found as he described, yet refused to admit that it belonged to a remote antiquity. In writing subsequently to Falconer and to Prestwich, he pleaded for his jaw in words that were pathetic. He felt that the halo of his success was dimmed, and never quite recovered from his keen disappointment. Yet he had support among the members of the Commission, who were his distinguished countrymen, and might well have been content to leave the age of this famous human jaw as it rested in the minds of his English friends—in doubt. His early researches had thrown a flood of light upon a subject which had been shunned, so beset was it with difficulties: in obtaining the public recognition of his flint haches as the tools and weapons of primitive man, he had achieved a great work.

Could he have been but spared to witness the hold that his discoveries eventually obtained over the public mind! Could he only have foreseen the growth of the subject in seven-and-thirty years, how great would have been his triumph! His indomitable energy and far-seeing sagacity had given the first impetus to a subject which has grown into a new science, and geologists all over the world have set themselves to seek (and have found) those rudely wrought weapons and tools of flint and stone, fashioned by savage man before the use of metals was known. And the inquiry, once started, has not been limited to the search in the Valley Drifts, of which the flint implements have become historical. The horizon has widened; evidence is forthcoming which shows that flint implements of a still ruder type are found in a Drift on the summit of hills, and to which a much older date has been assigned than to the Valley Drifts.1 This new field of research is now in course of active exploration, and the discoveries in it already shadow forth results that are remarkable, inasmuch as they point to the still greater antiquity of the human race.

1 See papers by Prestwich, Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc., voL xlvii. p. 126, and Journ. Anthropol. Inst., vol. xxi. p. 246.

Lady Prestwich was the wife of Sir Joseph Prestwich, professor of Geology at the University of Oxford, whom she accompanied on his scientific travels. Abbeville is situated in the Somme valley, north-west of Amiens.

10 September Today in Science History

page for births deaths and events on

Boucher's date of birth.

10 September Today in Science History

page for births deaths and events on

Boucher's date of birth. Men

Among the Mammoths: Victorian science and the discovery of human

prehistory, by A. Bowdoin Van Riper - book

recommendation.

Men

Among the Mammoths: Victorian science and the discovery of human

prehistory, by A. Bowdoin Van Riper - book

recommendation.