(source)

(source)

|

Michael Faraday

(22 Sep 1791 - 25 Aug 1867)

English physicist and chemist who was a great experimentalist. His major contributions included the early understanding of electromagnetism.

|

Science Quotes by Michael Faraday (59 quotes)

>> Click for Michael Faraday Quotes on | Candle | Discovery | Electrolysis | Knowledge | Nomenclature |

>> Click for Michael Faraday Quotes on | Candle | Discovery | Electrolysis | Knowledge | Nomenclature |

Click here or on image for larger picture (800 x 1000 px)

Adapted from portrait by Thomas Phillips (1842) (source)

[I have a great] distaste for controversy…. I have often seen it do great harm, and yet remember few cases in natural knowledge where it has helped much either to pull down error or advance truth. Criticism, on the other hand, is of much value.

— Michael Faraday

In letter (6 May 1841) to Robert Hare, an American Chemist, collected in Experimental Researches in Electricity (1844), Vol. 2, 275, as a footnote added to a reprint of 'On Dr. Hare’s Second Letter, and on the Chemical and Contact Theories of the Voltaic Battery', London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine (1843), 23.

[I have] a strong conviction that controversial reply and rejoinder is but a vain occupation.

— Michael Faraday

In letter (11 Mar 1843) to R. Taylor, collected in Experimental Researches in Electricity (1844), Vol. 2, 274-2755. Published earlier as 'On Dr. Hare’s Second Letter, and on the Chemical and Contact Theories of the Voltaic Battery', London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine (1843), 23.

[On gold, silver, mercury, platinum, palladium, rhodium, iridium, osmium:] As in their physical properties so in their chemical properties. Their affinities being weaker, (the noble metals) do not present that variety of combinations, belonging to the more common metals, which renders them so extensively useful in the arts; nor are they, in consequence, so necessary and important in the operations of nature. They do not assist in her hands in breaking down rocks and strata into soil, nor do they help man to make that soil productive or to collect for him its products.

— Michael Faraday

From 13th Lecture in 1818, in Bence Jones, The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 254.

[On Oxygen, Chlorine, Iodine, Fluorine:] The most important division of ponderable substances seems to be that which represents their electrical energies or their respective inherent states. When the poles of a voltaic apparatus are introduced into a mixture of the simple substances, it is found that four of them go to the positive, while the rest evince their state by passing to the negative pole. As this division coincides with one resulting from a consideration of their most important properties, it is that which I shall adopt as the first.

— Michael Faraday

From 5th Lecture in 1816, in Bence Jones, The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 217-218.

[The new term] Physicist is both to my mouth and ears so awkward that I think I shall never use it. The equivalent of three separate sounds of i in one word is too much.

— Michael Faraday

Quoted in Sydney Ross, Nineteenth-Century Attitudes: Men of Science (1991), 10.

[The object of education is] to train the mind to ascertain the sequence of a particular conclusion from certain premises, to detect a fallacy, to correct undue generalisation, to prevent the growth of mistakes in reasoning. Everything in these must depend on the spirit and the manner in which the instruction itself is conveyed and honoured. If you teach scientific knowledge without honouring scientific knowledge as it is applied, you do more harm than good. I do think that the study of natural science is so glorious a school for the mind, that with the laws impressed on all these things by the Creator, and the wonderful unity and stability of matter, and the forces of matter, there cannot be a better school for the education of the mind.

— Michael Faraday

Giving Evidence (18 Nov 1862) to the Public Schools Commission. As quoted in John L. Lewis, 125 Years: The Physical Society & The Institute of Physics (1999), 168-169.

Astonishing how great the precautions that are needed in these delicate experiments. Patience. Patience.

— Michael Faraday

In Thomas Martin (ed.) Faraday’s Diary: Sept. 6, 1847 - Oct. 17, 1851 (1934), 228. Concerning his efforts (1849), to duplicate certain of Weber’s experiments. In the quote above, italics are added for words underlined in sentence as given 'The Scientific Grammar of Michael Faraday’s Diaries', Part I, 'The Classic of Science', A Classic and a Founder (1937), collected in Rosenstock-Huessy Papers (1981), Vol. 1, 3.

A lecturer should … give them [the audience] full reason to believe that all his powers have been exerted for their pleasure and instruction.

— Michael Faraday

In Letter to his friend Benjamin Abbott (11 Jun 1813), collected in Bence Jones, Life and Letters of Faraday, Vol. 1, 73. Faraday was age 21, less than a year since completing his bookbinder apprenticeship, and had decided upon “giving up trade and taking to science.” From several letters, various opinions about lecturing were gathered in an article, 'Faraday on Scientific Lecturing', Norman Locker (ed.), Nature (23 Oct 1873), 8, 524.

A man in twenty-four hours converts as much as seven ounces of carbon into carbonic acid; a milch cow will convert seventy ounces, and a horse seventy-nine ounces, solely by the act of respiration. That is, the horse in twenty-four hours burns seventy-nine ounces of charcoal, or carbon, in his organs of respiration to supply his natural warmth in that time ..., not in a free state, but in a state of combination.

— Michael Faraday

From the concluding lecture (8 Jan 1861) given to a juvenile audience at the Royal Institution, as published in A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861), 177.

A natural law regulates the advance of science. Where only observation can be made, the growth of knowledge creeps; where laboratory experiments can be carried on, knowledge leaps forward.

[Attributed, probably incorrectly]

[Attributed, probably incorrectly]

— Michael Faraday

Seen in various places, but Webmaster has found none with a source citation, and doubts the authenticity, because none found with attribution to Faraday prior to 1950. The earliest example Webmaster found is in 1929, by Walter Morley Fletcher in his Norman Lockyer Lecture. He refers to it as a “truism,” without mention of Faraday. He says “law of our state of being” rather than “natural law.” See the Walter Morley Fletcher page for more details.

All your names I and my friend approve of or nearly all as to sense & expression, but I am frightened by their length & sound when compounded. As you will see I have taken deoxide and skaiode because they agree best with my natural standard East and West. I like Anode & Cathode better as to sound, but all to whom I have shewn them have supposed at first that by Anode I meant No way.

— Michael Faraday

Letter (3 May 1834) to William Whewell, who coined the terms. In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1993), Vol. 2, 181. Note: Here “No way” is presumably not an idiomatic exclamation, but a misinterpretation from the Greek prefix, -a “not”or “away from,” and hodos meaning “way.” The Greek ἄνοδος anodos means “way up” or “ascent.”

Although we know nothing of what an atom is, yet we cannot resist forming some idea of a small particle, which represents it to the mind ... there is an immensity of facts which justify us in believing that the atoms of matter are in some way endowed or associated with electrical powers, to which they owe their most striking qualities, and amongst them their mutual chemical affinity.

[Summarizing his investigations in electrolysis.]

[Summarizing his investigations in electrolysis.]

— Michael Faraday

Experimental Researches in Electricity (1839), section 852. Cited in Laurie M. Brown, Abraham Pais, Brian Pippard, Twentieth Century Physics (1995), Vol. 1, 51.

As an answer to those who are in the habit of saying to every new fact, “What is its use?” Dr. Franklin says to such, “What is the use of an infant?” The answer of the experimentalist would be, “Endeavour to make it useful.”

— Michael Faraday

From 5th Lecture in 1816, in Bence Jones, The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 218.

At present we begin to feel impatient, and to wish for a new state of chemical elements. For a time the desire was to add to the metals, now we wish to diminish their number. They increase upon us continually, and threaten to enclose within their ranks the bounds of our fair fields of chemical science. The rocks of the mountain and the soil of the plain, the sands of the sea and the salts that are in it, have given way to the powers we have been able to apply to them, but only to be replaced by metals.

— Michael Faraday

In his 16th Lecture of 1818, in Bence Jones, The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 256-257.

But I must confess I am jealous of the term atom; for though it is very easy to talk of atoms, it is very difficult to form a clear idea of their nature, especially when compounded bodies are under consideration.

— Michael Faraday

'On the Absolute Quantity of Electricity Associated with the Particles or Atoms of Matter,' (31 Dec 1833), published in Philosophical Transactions (Jan 1834) as part of Series VII. Collected in Experimental Researches in Electricity: Reprinted from the Philosophical Transactions of 1831-1838 (1839), 256.

Electricity is often called wonderful, beautiful; but it is so only in common with the other forces of nature. The beauty of electricity or of any other force is not that the power is mysterious, and unexpected, touching every sense at unawares in turn, but that it is under law, and that the taught intellect can even govern it largely. The human mind is placed above, and not beneath it, and it is in such a point of view that the mental education afforded by science is rendered super-eminent in dignity, in practical application and utility; for by enabling the mind to apply the natural power through law, it conveys the gifts of God to man.

— Michael Faraday

Notes for a Friday Discourse at the Royal Institution (1858).

Gravity. Surely this force must be capable of an experimental relation to electricity, magnetism, and the other forces, so as to bind it up with them in reciprocal action and equivalent effect.

— Michael Faraday

Notebook entry (19 Mar 1849). In Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 2, 252.

I ... express a wish that you may, in your generation, be fit to compare to a candle; that you may, like it, shine as lights to those about you; that, in all your actions, you may justify the beauty of the taper by making your deeds honourable and effectual in the discharge of your duty to your fellow-men.

— Michael Faraday

The closing of the concluding lecture (8 Jan 1861) given to a juvenile audience at the Royal Institution, as published in A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861), 183. The tradition of these Christmas lectures continues to the present day.

I am busy just now again on Electro-Magnetism and think I have got hold of a good thing but can't say; it may be a weed instead of a fish that after all my labour I may at last pull up.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to Richard Phillips, 23 Sep 1831. In Michael Faraday, Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 2, 3.

I could trust a fact and always cross-question an assertion.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to De La Rive, 2 Oct 1858. Quoted by Frank A. J. L. James.

I happen to have discovered a direct relation between magnetism and light, also electricity and light, and the field it opens is so large and I think rich.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to Christian Schönbein (13 Nov 1845), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), 148.

I have been arranging certain experiments in reference to the notion that Gravity itself may be practically and directly related by experiment to the other powers of matter and this morning proceeded to make them. It was almost with a feeling of awe that I went to work, for if the hope should prove well founded, how great and mighty and sublime in its hitherto unchangeable character is the force I am trying to deal with, and how large may be the new domain of knowledge that may be opened up to the mind of man.

— Michael Faraday

In Thomas Martin (ed.) Faraday’s Diary: Sept. 6, 1847 - Oct. 17, 1851 (1934), 156.

I have been driven to assume for some time, especially in relation to the gases, a sort of conducting power for magnetism. Mere space is Zero. One substance being made to occupy a given portion of space will cause more lines of force to pass through that space than before, and another substance will cause less to pass. The former I now call Paramagnetic & the latter are the diamagnetic. The former need not of necessity assume a polarity of particles such as iron has with magnetic, and the latter do not assume any such polarity either direct or reverse. I do not say more to you just now because my own thoughts are only in the act of formation, but this I may say: that the atmosphere has an extraordinary magnetic constitution, & I hope & expect to find in it the cause of the annual & diurnal variations, but keep this to yourself until I have time to see what harvest will spring from my growing ideas.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to William Whewell, 22 Aug 1850. In L. Pearce Williams (ed.), The Selected Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1971), Vol. 2, 589.

I have been so electrically occupied of late that I feel as if hungry for a little chemistry: but then the conviction crosses my mind that these things hang together under one law & that the more haste we make onwards each in his own path the sooner we shall arrive, and meet each other, at that state of knowledge of natural causes from which all varieties of effects may be understood & enjoyed.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to Eilhard Mitscherlich, 24 Jan 1838. In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1993), Vol. 2, 488.

I have long held an opinion, almost amounting to conviction, in common I believe with many other lovers of natural knowledge, that the various forms under which the forces of matter are made manifest have one common origin; or, in other words, are so directly related and mutually dependent, that they are convertible, as it were, one into another, and possess equivalents of power in their action.

— Michael Faraday

Paper read to the Royal Institution (20 Nov 1845). 'On the Magnetization of Light and the Illumination of Magnetic Lines of Force', Series 19. In Experimental Researches in Electricity (1855), Vol. 3, 1. Reprinted from Philosophical Transactions (1846), 1.

I have never had any student or pupil under me to aid me with assistance; but have always prepared and made my experiments with my own hands, working & thinking at the same time. I do not think I could work in company, or think aloud, or explain my thoughts at the time. Sometimes I and my assistant have been in the Laboratory for hours & days together, he preparing some lecture apparatus or cleaning up, & scarcely a word has passed between us; — all this being a consequence of the solitary & isolated system of investigation; in contradistinction to that pursued by a Professor with his aids & pupils as in your Universities.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to C. Ransteed, 16 Dec 1857. In L. Pearce Williams (ed.), The Selected Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1971), Vol. 2, 888.

I have rather, however, been desirous of discovering new facts and new relations dependent on magneto-electric induction, than of exalting the force of those already obtained; being assured that the latter would find their full development hereafter.

— Michael Faraday

Read 12 Jan 1832, reprinted from Philosophical Transactions of 1831-1828, in 'Second Series', Experimental Researches in Electricity: Volume 1 (1839), 47.

I have taken your advice, and the names used are anode cathode anions cations and ions; the last I shall have but little occasion for. I had some hot objections made to them here and found myself very much in the condition of the man with his son and ass who tried to please every body; but when I held up the shield of your authority, it was wonderful to observe how the tone of objection melted away.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to William Whewell, 15 May 1834. In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1993), Vol. 2, 186.

I hope that in due time the chemists will justify their proceedings by some large generalisations deduced from the infinity of results which they have collected. For me I am left hopelessly behind and I will acknowledge to you that through my bad memory organic chemistry is to me a sealed book. Some of those here, [August] Hoffman for instance, consider all this however as scaffolding, which will disappear when the structure is built. I hope the structure will be worthy of the labour. I should expect a better and a quicker result from the study of the powers of matter, but then I have a predilection that way and am probably prejudiced in judgment.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to Christian Schönbein (9 Dec 1852), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), 209-210.

I purpose, in return for the honour you do us by coming to see what are our proceedings here, to bring before you, in the course of these lectures, the Chemical History of a Candle. I have taken this subject on a former occasion; and were it left to my own will, I should prefer to repeat it almost every year—so abundant is the interest that attaches itself to the subject, so wonderful are the varieties of outlet which it offers into the various departments of philosophy. There is not a law under which any part of this universe is governed which does not come into play, and is touched upon in these phenomena. There is no better, there is no more open door by which you can enter the study of natural philosophy, than by considering the physical phenomena of a candle.

— Michael Faraday

Opening of the first lecture (27 Dec 1860) delivered to a juvenile audience at the Royal Institution, as published in A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861), 9-10.

I require a term to express those bodies which can pass to the electrodes, or, as they are usually called, the poles. Substances are frequently spoken of as being electro-negative, or electro-positive, according as they go under the supposed influence of a direct attraction to the positive or negative pole. But these terms are much too significant for the use to which I should have to put them; for though the meanings are perhaps right, they are only hypothetical, and may be wrong; and then, through a very imperceptible, but still very dangerous, because continual, influence, they do great injury to science, by contracting and limiting the habitual view of those engaged in pursuing it. I propose to distinguish these bodies by calling those anions which go to the anode of the decomposing body; and those passing to the cathode, cations; and when I have occasion to speak of these together, I shall call them ions.

— Michael Faraday

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1834, 124, 79.

I think chemistry is being frittered away by the hairsplitting of the organic chemists; we have new compounds discovered, which scarcely differ from the known ones and when discovered are valueless—very illustrations perhaps of their refinements in analysis, but very little aiding the progress of true science.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to William Grove (5 Jan 1845), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), Footnote, 209.

I wanted some new names to express my facts in Electrical science without involving more theory than I could help & applied to a friend Dr Nicholl [his doctor], who has given me some that I intend to adopt for instance, a body decomposable by the passage of the Electric current, I call an ‘electrolyte’ and instead of saying that water is electro chemically decomposed I say it is ‘electrolyzed’. The intensity above which a body is decomposed beneath which it conducts without decomposition I call the ‘Electrolyte intensity’ &c &c. What have been called: the poles of the battery I call the electrodes they are not merely surfaces of metal, but even of water & air, to which the term poles could hardly apply without receiving a new sense. Electrolytes must consist of two parts which during the electrolization, are determined the one in the one direction, and the other towards the poles where they are evolved; these evolved substances I call zetodes, which are therefore the direct constituents of electrolites.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to William Whewell (24 Apr 1834). In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday: Volume 2, 1832-1840 (1993), 176.

I will simply express my strong belief, that that point of self-education which consists in teaching the mind to resist its desires and inclinations, until they are proved to be right, is the most important of all, not only in things of natural philosophy, but in every department of dally life.

— Michael Faraday

'Observations On Mental Education', a lecture before the Prince Consort and the Royal Institution, 6 May 1854. Experimental researches in chemistry and physics (1859), 477.

If the term education may be understood in so large a sense as to include all that belongs to the improvement of the mind, either by the acquisition of the knowledge of others or by increase of it through its own exertions, we learn by them what is the kind of education science offers to man. It teaches us to be neglectful of nothing — not to despise the small beginnings, for they precede of necessity all great things in the knowledge of science, either pure or applied.

— Michael Faraday

'Science as a Branch of Education', lecture to the Royal Institution, 11 Jun 1858. Reprinted in The Mechanics Magazine (1858), 49, 11.

In knowledge that man only is to be condemned and despised who is not in a state of transition.

— Michael Faraday

As quoted, without citation in Lecture, 'The Study of History' (11 Jun 1895) delivered at Cambridge, published as Lord Acton, A Lecture on The Study of History (1895), 54.

It is the great beauty of our science that advancement in it, whether in a degree great or small, instead of exhausting the subject of research, opens the doors to further and more abundant knowledge, overflowing with beauty and utility.

— Michael Faraday

From 'Experimental Researches in Electricity: Series VII: § 13. On the absolute quantity of Electricity associated with the particles or atoms of Matter', Philosophic Transactions, (text dated 31 Dec 1833, received 9 Jan 1834, read 13 Feb 1834). Collected in Experimental Researches in Electricity (1839), Vol. 1, 257.

Lectures which really teach will never be popular; lectures which are popular will never really teach.

— Michael Faraday

(1846.) In Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Michael Faraday (1870), Vol. 2, 228. Faraday made this statement to the Secretary of the Royal Institution who consulted him regarding evening lectures. Faraday’s reply began with, “I see no objection to evening lectures if you can find a fit man to give them. As to popular lectures (which at the same time are to be respectable and sound), none are more difficult to find.”

Magnetic lines of force convey a far better and purer idea than the phrase magnetic current or magnetic flood: it avoids the assumption of a current or of two currents and also of fluids or a fluid, yet conveys a full and useful pictorial idea to the mind.

— Michael Faraday

Diary Entry for 10 Sep 1854. In Thomas Martin (ed.), Faraday's Diary: Being the Various Philosophical Notes of Experimental Investigation (1935), Vol. 6, 315.

Men of science, fit to teach, hardly exist. There is no demand for such men. The sciences make up life; they are important to life. The highly educated man fails to understand the simplest things of science, and has no peculiar aptitude for grasping them. I find the grown-up mind coming back to me with the same questions over and over again.

— Michael Faraday

Giving Evidence (18 Nov 1862) to the Public Schools Commission. As quoted in John L. Lewis, 125 Years: The Physical Society & The Institute of Physics (1999), 168.

Nothing is too wonderful to be true if it be consistent with the laws of nature.

— Michael Faraday

Laboratory notebook (19 Mar 1850), while musing on the possible relation of gravity to electricy. In Michael Faraday and Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), 253

Now I must take you to a very interesting part of our subject—to the relation between the combustion of a candle and that living kind of combustion which goes on within us. In every one of us there is a living process of combustion going on very similar to that of a candle, and I must try to make that plain to you. For it is not merely true in a poetical sense—the relation of the life of man to a taper; and if you will follow, I think I can make this clear.

— Michael Faraday

From the concluding lecture (8 Jan 1861) given to a juvenile audience at the Royal Institution, as published in A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861), 167.

Occasionally and frequently the exercise of the judgment ought to end in absolute reservation. It may be very distasteful, and great fatigue, to suspend a conclusion; but as we are not infallible, so we ought to be cautious; we shall eventually find our advantage, for the man who rests in his position is not so far from right as he who, proceeding in a wrong direction, is ever increasing his distance.

— Michael Faraday

Lecture at the Royal Institution, 'Observations on the Education of the Judgment'. Collected in Edward Livingston Youmans (ed)., Modern Culture (1867), 219.

The cases of action at a distance are becoming, in a physical point of view, daily more and more important. Sound, light, electricity, magnetism, gravitation, present them as a series.

The nature of sound and its dependence on a medium we think we understand, pretty well. The nature of light as dependent on a medium is now very largely accepted. The presence of a medium in the phenomena of electricity and magnetism becomes more and more probable daily. We employ ourselves, and I think rightly, in endeavouring to elucidate the physical exercise of these forces, or their sets of antecedents and consequents, and surely no one can find fault with the labours which eminent men have entered upon in respect of light, or into which they may enter as regards electricity and magnetism. Then what is there about gravitation that should exclude it from consideration also? Newton did not shut out the physical view, but had evidently thought deeply of it; and if he thought of it, why should not we, in these advanced days, do so too?

The nature of sound and its dependence on a medium we think we understand, pretty well. The nature of light as dependent on a medium is now very largely accepted. The presence of a medium in the phenomena of electricity and magnetism becomes more and more probable daily. We employ ourselves, and I think rightly, in endeavouring to elucidate the physical exercise of these forces, or their sets of antecedents and consequents, and surely no one can find fault with the labours which eminent men have entered upon in respect of light, or into which they may enter as regards electricity and magnetism. Then what is there about gravitation that should exclude it from consideration also? Newton did not shut out the physical view, but had evidently thought deeply of it; and if he thought of it, why should not we, in these advanced days, do so too?

— Michael Faraday

Letter to E. Jones, 9 Jun 1857. In Michael Faraday, Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 2, 387.

The laws of nature, as we understand them, are the foundation of our knowledge in natural things. So much as we know of them has been developed by the successive energies of the highest intellects, exerted through many ages. After a most rigid and scrutinizing examination upon principle and trial, a definite expression has been given to them; they have become, as it were, our belief or trust. From day to day we still examine and test our expressions of them. We have no interest in their retention if erroneous. On the contrary, the greatest discovery a man could make would be to prove that one of these accepted laws was erroneous, and his greatest honour would be the discovery.

— Michael Faraday

Experimental researches in chemistry and physics (1859), 469.

The secret [of my success] is comprised in three words — Work, Finish, Publish.

— Michael Faraday

Advice to a young chemist, recalled in obituary, 'Faraday', in William Crookes (ed.), The Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science (30 Aug 1867), 16, No. 404, 111. William Crookes was identified as that young chemist (and the obituary writer) in Silvanus Phillips Thompson, Michael Faraday: His Life and Work (1898), 267.

The wise man, however, will avoid partial views of things. He will not, with the miser, look to gold and silver as the only blessings of life; nor will he, with the cynic, snarl at mankind for preferring them to copper and iron. … That which is convenient is that which is useful, and that which is useful is that which is valuable.

— Michael Faraday

From 13th Lecture in 1818, in Bence Jones, The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 255.

The world little knows how many of the thoughts and theories which have passed through the mind of a scientific investigator, have been crushed in silence and secrecy by his own severe criticism and adverse examination; that in the most successful instances not a tenth of the suggestions, the hopes, the wishes, the preliminary conclusions have been realized.

— Michael Faraday

In 'Observations On Mental Education', a lecture before the Prince Consort and the Royal Institution (6 May 1854). Experimental Researches in Chemistry and Physics (1859), 486.

To day we made the grand experiment of burning the diamond and certainly the phenomena presented were extremely beautiful and interesting… The Duke’s burning glass was the instrument used to apply heat to the diamond. It consists of two double convex lenses … The instrument was placed in an upper room of the museum and having arranged it at the window the diamond was placed in the focus and anxiously watched. The heat was thus continued for 3/4 of an hour (it being necessary to cool the globe at times) and during that time it was thought that the diamond was slowly diminishing and becoming opaque … On a sudden Sir H Davy observed the diamond to burn visibly, and when removed from the focus it was found to be in a state of active and rapid combustion. The diamond glowed brilliantly with a scarlet light, inclining to purple and, when placed in the dark, continued to burn for about four minutes. After cooling the glass heat was again applied to the diamond and it burned again though not for nearly so long as before. This was repeated twice more and soon after the diamond became all consumed. This phenomenon of actual and vivid combustion, which has never been observed before, was attributed by Sir H Davy to be the free access of air; it became more dull as carbonic acid gas formed and did not last so long.

— Michael Faraday

Entry (Florence, 27 Mar 1814) in his foreign journal kept whilst on a continental tour with Sir Humphry Davy. In Michael Faraday, Bence Jones (ed.), The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870), Vol. 1, 119. Silvanus Phillips Thompson identifies the Duke as the Grand Duke of Tuscany, in Michael Faraday, His Life and Work (1901), 21.

Tyndall, ... I must remain plain Michael Faraday to the last; and let me now tell you, that if accepted the honour which the Royal Society desires to confer upon me, I would not answer for the integrity of my intellect for a single year.

On being offered the Presidency of the Royal Society.

On being offered the Presidency of the Royal Society.

— Michael Faraday

John Tyndall, Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 157-8.

What a delight it is to think that you are quietly & philosophically at work in the pursuit of science... rather than fighting amongst the crowd of black passions & motives that seem now a days to urge men every where into action. What incredible scenes every where, what unworthy motives ruled for the moment, under high sounding phrases and at the last what disgusting revolutions.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to C. Schrenbein, 15 Dec 1848. In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1996), Vol. 3, 742.

What a weak, credulous, incredulous, unbelieving, superstitious, bold, frightened, what a ridiculous world ours is, as far as concerns the mind of man. How full of inconsistencies, contradictions and absurdities it is. I declare that taking the average of many minds that have recently come before me … I should prefer the obedience, affections and instinct of a dog before it.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to C. Schoenbein (25 Jul 1853). In Georg W.A. Kahlbaum and Francis V. Darbishire (eds.), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), 215.

When I quitted business and took to science as a career, I thought I had left behind me all the petty meannesses and small jealousies which hinder man in his moral progress; but I found myself raised into another sphere, only to find poor human nature just the same everywhere—subject to the same weaknesses and the same self-seeking, however exalted the intellect.

— Michael Faraday

As quoted “as well as I can recollect” by Mrs. Cornelia Crosse, wife of the scientist Andrew Crosse. She was with him during a visit by Andrew to see his friend Faraday at the Royal Institution, and she had some conversation with him. This was Faraday’s reply to her comment that he must be happy to have elevated himself (presumably, from his apprenticeship as a bookbinder) above all the “meaner aspects and lower aims of common life.” As stated in John Hall Gladstone, Michael Faraday (1872), 117.

Who would not have been laughed at if he had said in 1800 that metals could be extracted from their ores by electricity or that portraits could be drawn by chemistry.

[Commenting on Becquerel’s process for extracting metals by voltaic means.]

[Commenting on Becquerel’s process for extracting metals by voltaic means.]

— Michael Faraday

Letter (20 Aug 1847), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), footnote, 209.

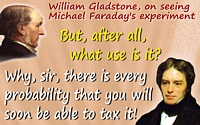

Why, sir, there is every probability that you will soon be able to tax it!

Said to William Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, when he asked about the practical worth of electricity.

Said to William Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, when he asked about the practical worth of electricity.

— Michael Faraday

Quoted in R. A. Gregory, Discovery, Or The Spirit and Service of Science (1916), 3.

With respect to Committees as you would perceive I am very jealous of their formation. I mean working committees. I think business is always better done by few than by many. I think also the working few ought not to be embarrassed by the idle many and further I think the idle many ought not to be honoured by association with the working few.—I do not think that my patience has ever come nearer to an end than when compelled to hear … long rambling malapropros enquiries of members who still have nothing in consequence to propose that shall advance the business.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to John William Lubbock (6 Dec 1833). In Frank A.J.L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday: Volume 2, 1832-1840 (1993), 160. The original text spelling of “embarrased” has been edited for ease of reading in the above quote.

You can hardly imagine how I am struggling to exert my poetical ideas just now for the discovery of analogies & remote figures respecting the earth, Sun & all sorts of things—for I think it is the true way (corrected by judgement) to work out a discovery.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to C. Schrenbein, 13th Nov, 1845. In Frank A. J. L. James (ed.), The Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1996), Vol. 3, 428.

You will be astonished when I tell you what this curious play of carbon amounts to. A candle will burn some four, five, six, or seven hours. What, then, must be the daily amount of carbon going up into the air in the way of carbonic acid! ... Then what becomes of it? Wonderful is it to find that the change produced by respiration ... is the very life and support of plants and vegetables that grow upon the surface of the earth.

— Michael Faraday

From the concluding lecture (8 Jan 1861) given to a juvenile audience at the Royal Institution, as published in A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861), 177.

Your remarks upon chemical notation with the variety of systems which have arisen, &c., &c., had almost stirred me up to regret publicly that such hindrances to the progress of science should exist. I cannot help thinking it a most unfortunate thing that men who as experimentalists & philosophers are the most fitted to advance the general cause of science & knowledge should by promulgation of their own theoretical views under the form of nomenclature, notation, or scale, actually retard its progress.

— Michael Faraday

Letter to William Whewell (21 Feb 1831). In Isaac Todhunter, William Whewell, An Account of his Writings (1876), Vol. 1., 307. Faraday may have been referring to a paper by Whewell published in the Journal of the Royal Institution of England (1831), 437-453.

Quotes by others about Michael Faraday (32)

Sir H. Davy's greatest discovery was Michael Faraday.

'Michael Faraday', in Paul Harvey (ed.), The Oxford Companion to English Literature (1932), 279.

To him [Faraday], as to all true philosophers, the main value of a fact was its position and suggestiveness in the general sequence of scientific truth.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 84.

His [Faraday’s] soul was above all littleness and proof to all egotism.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 104.

His [Faraday’s] third great discovery is the Magnetization of Light, which I should liken to the Weisshorn among mountains—high, beautiful, and alone.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 146.

Taking him for all and all, I think it will be conceded that Michael Faraday was the greatest experimental philosopher the world has ever seen; and I will add the opinion, that the progress of future research will tend, not to dim or to diminish, but to enhance and glorify the labours of this mighty investigator.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 147.

The contemplation of Nature, and his own relation to her, produced in Faraday, a kind of spiritual exaltation which makes itself manifest here. His religious feeling and his philosophy could not be kept apart; there was an habitual overflow of the one into the other.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 152.

Er riecht die Wahrheit,

He [Faraday] smells the truth.

He [Faraday] smells the truth.

Quoted in John Tyndall, Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 45.

You must not say that this cannot be, or that that is contrary to nature. You do not know what Nature is, or what she can do; and nobody knows; not even Sir Roderick Murchison, or Professor Huxley, or Mr. Darwin, or Professor Faraday, or Mr. Grove, or any other of the great men whom good boys are taught to respect. They are very wise men; and you must listen respectfully to all they say: but even if they should say, which I am sure they never would, “That cannot exist. That is contrary to nature,” you must wait a little, and see; for perhaps even they may be wrong.

The Water-babies (1886), 81.

Ohm found that the results could be summed up in such a simple law that he who runs may read it, and a schoolboy now can predict what a Faraday then could only guess at roughly. By Ohm's discovery a large part of the domain of electricity became annexed by Coulomb's discovery of the law of inverse squares, and completely annexed by Green's investigations. Poisson attacked the difficult problem of induced magnetisation, and his results, though differently expressed, are still the theory, as a most important first approximation. Ampere brought a multitude of phenomena into theory by his investigations of the mechanical forces between conductors supporting currents and magnets. Then there were the remarkable researches of Faraday, the prince of experimentalists, on electrostatics and electrodynamics and the induction of currents. These were rather long in being brought from the crude experimental state to a compact system, expressing the real essence. Unfortunately, in my opinion, Faraday was not a mathematician. It can scarely be doubted that had he been one, he would have anticipated much later work. He would, for instance, knowing Ampere's theory, by his own results have readily been led to Neumann’s theory, and the connected work of Helmholtz and Thomson. But it is perhaps too much to expect a man to be both the prince of experimentalists and a competent mathematician.

From article 'Electro-magnetic Theory II', in The Electrician (16 Jan 1891), 26, No. 661, 331.

Even if I could be Shakespeare I think that I should still choose to be Faraday.

In 1925, attributed. Walter M. Elsasser, Memoirs of a Physicist in the Atomic Age (1978), epigraph.

There is in the chemist a form of thought by which all ideas become visible in the mind as strains of an imagined piece of music. This form of thought is developed in Faraday in the highest degree, whence it arises that to one who is not acquainted with this method of thinking, his scientific works seem barren and dry, and merely a series of researches strung together, while his oral discourse when he teaches or explains is intellectual, elegant, and of wonderful clearness.

Autobiography, 257-358. Quoted in William H. Brock, Justus Von Liebig (2002), 9.

At no period of [Michael Faraday’s] unmatched career was he interested in utility. He was absorbed in disentangling the riddles of the universe, at first chemical riddles, in later periods, physical riddles. As far as he cared, the question of utility was never raised. Any suspicion of utility would have restricted his restless curiosity. In the end, utility resulted, but it was never a criterion to which his ceaseless experimentation could be subjected.

'The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge', Harper's Magazine (Jun/Nov 1939), No. 179, 546. In Hispania (Feb 1944), 27, No. 1, 77.

The most startling result of Faraday’s Law is perhaps this. If we accept the hypothesis that the elementary substances are composed of atoms, we cannot avoid concluding that electricity also, positive as well as negative, is divided into definite elementary portions, which behave like atoms of electricity.

Faraday Lecture (1881). In 'On the Modern Development of Faraday's Conception of Electricity', Journal of the Chemical Society 1881, 39, 290. It is also stated in the book by Laurie M. Brown, Abraham Pais and Brian Pippard, Twentieth Century P, Vol. 1, 52, that this is 'a statement which explains why in subsequent years the quantity e was occasionally referred to in German literature as das Helmholtzsche Elementarquantum'.

[The new term] Physicist is both to my mouth and ears so awkward that I think I shall never use it. The equivalent of three separate sounds of i in one word is too much.

Quoted in Sydney Ross, Nineteenth-Century Attitudes: Men of Science (1991), 10.

As for hailing [the new term] scientist as 'good', that was mere politeness: Faraday never used the word, describing himself as a natural philosopher to the end of his career.

Nineteenth-Century Attitudes: Men of Science (1991), 10.

It is told of Faraday that he refused to be called a physicist; he very much disliked the new name as being too special and particular and insisted on the old one, philosopher, in all its spacious generality: we may suppose that this was his way of saying that he had not over-ridden the limiting conditions of class only to submit to the limitation of a profession.

Commentary (Jun 1962), 33, 461-77. Cited by Sydney Ross in Nineteenth-Century Attitudes: Men of Science (1991), 11.

To what part of electrical science are we not indebted to Faraday? He has increased our knowledge of the hidden and unknown to such an extent, that all subsequent writers are compelled so frequently to mention his name and quote his papers, that the very repetition becomes monotonous. [How] humiliating it may be to acknowledge so great a share of successful investigation to one man...

In the Second Edition ofElements of Electro-Metallurgy: or The Art of Working in Metals by the Galvanic Fluid (143), 128.

How fortunate for civilization, that Beethoven, Michelangelo, Galileo and Faraday were not required by law to attend schools where their total personalities would have been operated upon to make them learn acceptable ways of participating as members of “the group.”

In speech, 'Education for Creativity in the Sciences', Conference at New York University, Washington Square. As quoted by Gene Currivan in 'I.Q. Tests Called Harmful to Pupil', New York Times (16 Jun 1963), 66.

Faraday, who had no narrow views in regard to education, deplored the future of our youth in the competition of the world, because, as he said with sadness, “our school-boys, when they come out of school, are ignorant of their ignorance at the end of all that education.”

In Inaugural Presidential Address (9 Sep 1885) to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Aberdeen, Scotland, 'Relations of Science to the Public Weal', Report to the Fifty-Fifth Meeting of the British Association (1886), 11.

We then got to Westminster Abbey and, moving about unguided, we found the graves of Newton, Rutherford, Darwin, Faraday, and Maxwell in a cluster.

(1980). In Isaac Asimov’s Book of Science and Nature Quotations (1988), 294.

What agencies of electricity, gravity, light, affinity combine to make every plant what it is, and in a manner so quiet that the presence of these tremendous powers is not ordinarily suspected. Faraday said, “A grain of water is known to have electric relations equivalent to a very powerful flash of lightning.”

In 'Perpetual Forces', North American Review (1877), No. 125. Collected in Ralph Waldo Emerson and James Elliot Cabot (ed.), Lectures and Biographical Sketches (1883), 60.

The momentous laws of induction between currents and between currents and magnets were discovered by Michael Faraday in 1831-32. Faraday was asked: “What is the use of this discovery?” He answered: “What is the use of a child—it grows to be a man.” Faraday’s child has grown to be a man and is now the basis of all the modern applications of electricity.

In An Introduction to Mathematics (1911), 34-35.

We sometimes are inclined to look into a science not our own as into a catalogue of results. In Faraday’s Diary, it becomes again what it really is, a campaign of mankind, balancing in any given moment, past experience, present speculation, and future experimentation, in a unique concoction of scepticism, faith, doubt, and expectation.

In 'The Scientific Grammar of Michael Faraday’s Diaries', Part I, 'The Classic of Science', A Classic and a Founder (1937), collected in Rosenstock-Huessy Papers (1981), Vol. 1, 1. The context is that Faraday, for “more than four decades. He was in the habit of describing each experiment and every observation inside and outside his laboratory, in full and accurate detail, on the very day they were made. Many of the entries discuss the consequences which he drew

from what he observed. In other cases they outline the proposed course of research for the future.”

Faraday thinks from day to day, against a background of older thinking, and anticipating new facts of tomorrow. In other words, he thinks in three dimensions of time; past, present, and future.

In 'The Scientific Grammar of Michael Faraday’s Diaries', Part I, 'The Classic of Science', A Classic and a Founder (1937), collected in Rosenstock-Huessy Papers (1981), Vol. 1, 1.

Faraday, … by his untiring faithfulness in keeping his diary, contributes to our understanding the objects of his scientific research in magnetism, electricity and light, but he also makes us understand the scientist himself, as a living subject, the mind in action.

In 'The Scientific Grammar of Michael Faraday’s Diaries', Part I, 'The Classic of Science', A Classic and a Founder (1937), collected in Rosenstock-Huessy Papers (1981), Vol. 1, 2.

William Blake called division the sin of man; Faraday was a great man because he was utterly undivided. His whole, very harmonious, very well balanced, … and used the brain in the limited

way in which it is useful…. [H]e built up his few but precious speculations. Their simplicity rivals with their forcefulness.

In 'The Scientific Grammar of Michael Faraday’s Diaries', Part I, 'The Classic of Science', A Classic and a Founder (1937), collected in Rosenstock-Huessy Papers (1981), Vol. 1, 7.

When Faraday filled space with quivering lines of force, he was bringing mathematics into electricity. When Maxwell stated his famous laws about the electromagnetic field it was mathematics. The relativity theory of Einstein which makes gravity a fiction, and reduces the mechanics of the universe to geometry, is mathematical research.

In 'The Spirit of Research', III, 'Mathematical Research', in The Monist (Oct 1922), 32, No. 4, 542-543.

It has been said that no science is established on a firm basis unless its generalisations can be expressed in terms of number, and it is the special province of mathematics to assist the investigator in finding numerical relations between phenomena. After experiment, then mathematics. While a science is in the experimental or observational stage, there is little scope for discerning numerical relations. It is only after the different workers have “collected data” that the mathematician is able to deduce the required generalisation. Thus a Maxwell followed Faraday and a Newton completed Kepler.

In Higher Mathematics for Students of Chemistry and Physics (1902), 3.

Newton’s passage from a falling apple to a falling moon was an act of the prepared imagination. Out of the facts of chemistry the constructive imagination of Dalton formed the atomic theory. Davy was richly endowed with the imaginative faculty, while with Faraday its exercise was incessant, preceding, accompanying and guiding all his experiments. His strength and fertility as a discoverer are to be referred in great part to the stimulus of the imagination.

In 'The Scientific Use of the Imagination', Fragments of Science: A Series of Detached Essays, Addresses, and Reviews (1892), Vol. 2, 104.

If he [Faraday] had allowed his vision to be disturbed by considerations regarding the practical use of his discoveries, those discoveries would never have been made by him.

In Faraday as a Discoverer (1868), 43. Introducing a quote by Faraday explaining his preference to focus on research, and letting others find applications: “I have rather rather been desirous of discovering new facts and new relations dependent on magneto-electric induction, than of exalting the force of those already obtained; being assured that the latter would find their full development hereafter.” (1831). For that source, see Michael Faraday Quotations.

Almost all great advances have sprung originally from disinterested motives. Scientific discoveries have been made for their own sake and not for their utilization, and a race of men without a disinterested love of knowledge would never have achieved our present scientific technique. … Faraday, Maxwell, and Hertz, so far as can be discovered, never for a moment considered the possibility of any practical application of their investigations.

In The Scientific Outlook (1931), 152-153.

Scientists today are hampered by their low social and economic status. Long gone is the respect and independence given to Lavoisier, Darwin, Faraday, Maxwell, Perkin, Curie and Einstein. Hardly any laboratory scientist anywhere is as free as a good writer can be. Indeed I suspect that the only scientists we know well are those who can write entertaining books; the real contributors to knowledge are mostly unknown.

In The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate Crisis & The Fate of Humanity (2006, 2007), 93.

See also:

- 22 Sep - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Faraday's birth.

- Michael Faraday on Pollution of the River Thames - Letter to the Editor, The Times (7 July 1885).

- Michael Faraday - Light-House Illumination - The Electric Light

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “You will soon be able to tax it!” - Medium image (500 x 350 px)

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “You will soon be able to tax it!” - Large image (800 x 600 px)

- Large color picture of Michael Faraday (800 x 1000 px)

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “Always cross-question an assertion” - Medium image (500 x 350 px)

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “Always cross-question an assertion” - Large image (800 x 600 px)

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “I am jealous of the term atom” - Medium image (500 x 350 px)

- Michael Faraday - context of quote “I am jealous of the term atom” - Large image (800 x 600 px)

- Michael Faraday - Scientific Worthy - article from Nature (1873)

- Michael Faraday, Christmas Lecturer - transcript of a 1940s radio talk by Charles F. Kettering.

- The Intangible in Human Progress - Michael Faraday mentioned in transcript of a 1940s radio talk by Charles F. Kettering.

- The Electric Life Of Michael Faraday, by Alan W. Hirshfeld. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Michael Faraday.

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --