Hope Quotes (327 quotes)

“Hope springs eternal in the human breast,” and is as necessary to life as the act of breathing.

Quoted, without citation, in front matter to T. A. Edison Foundation, Lewis Howard Latimer: A Black Inventor: a Biography and Related Experiments You Can Do (1973). If you know the primary source, please contact Webmaster.

(1) I have told you more than I know about osteoporosis. (2) What I have told you is subject to change without notice. (3) I hope I raised more questions than I have given answers. (4) In any case, as usual, a lot more work is necessary.

Conclusion of one of his papers.

Conclusion of one of his papers.

In Barry G. Firkin, Judith A. Whitworth, Dictionary of Medical Eponyms (1996), 5.

[1665-10-16] But Lord, how empty the streets are, and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets, full of sores, and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this dead, and that man sick, and so many in this place, and so many in that. And they tell me that in Westminster there is never a physitian, and but one apothecary left, all being dead - but that there are great hopes of a great decrease this week. God send it.

Diary of Samuel Pepys (16 Oct 1665)

[1665-11-22] I heard this day that the plague is come very low; that is 600 and odd - and great hopes of a further decrease, because of this day's being a very exceeding hard frost - and continues freezing. ...

Diary of Samuel Pepys (22 Nov 1665)

[Civilization] is a highly complicated invention which has probably been made only once. If it perished it might never be made again. … But it is a poor thing. And if it to be improved there is no hope save in science.

In The Inequality of Man: And Other Essays (1937), 141.

[Euclid's Elements] has been for nearly twenty-two centuries the encouragement and guide of that scientific thought which is one thing with the progress of man from a worse to a better state. The encouragement; for it contained a body of knowledge that was really known and could be relied on, and that moreover was growing in extent and application. For even at the time this book was written—shortly after the foundation of the Alexandrian Museum—Mathematics was no longer the merely ideal science of the Platonic school, but had started on her career of conquest over the whole world of Phenomena. The guide; for the aim of every scientific student of every subject was to bring his knowledge of that subject into a form as perfect as that which geometry had attained. Far up on the great mountain of Truth, which all the sciences hope to scale, the foremost of that sacred sisterhood was seen, beckoning for the rest to follow her. And hence she was called, in the dialect of the Pythagoreans, ‘the purifier of the reasonable soul.’

From a lecture delivered at the Royal Institution (Mar 1873), collected postumously in W.K. Clifford, edited by Leslie Stephen and Frederick Pollock, Lectures and Essays, (1879), Vol. 1, 296.

[First use of the term science fiction:] We hope it will not be long before we may have other works of Science-Fiction [like Richard Henry Horne's The Poor Artist], as we believe such books likely to fulfil a good purpose, and create an interest, where, unhappily, science alone might fail.

[Thomas] Campbell says, that “Fiction in Poetry is not the reverse of truth, but her soft and enchanting resemblance.” Now this applies especially to Science-Fiction, in which the revealed truths of Science may be given interwoven with a pleasing story which may itself be poetical and true—thus circulating a knowledge of Poetry of Science, clothed in a garb of the Poetry of life.

[Thomas] Campbell says, that “Fiction in Poetry is not the reverse of truth, but her soft and enchanting resemblance.” Now this applies especially to Science-Fiction, in which the revealed truths of Science may be given interwoven with a pleasing story which may itself be poetical and true—thus circulating a knowledge of Poetry of Science, clothed in a garb of the Poetry of life.

In A Little Earnest Book Upon a Great Old Subject (1851), 137.

[Luis] Alvarez's whole approach to physics was that of an entrepreneur, taking big risks by building large new projects in the hope of large rewards, although his pay was academic rather than financial. He had drawn around him a group of young physicists anxious to try out the exciting ideas he was proposing.

As quoted in Walter Sullivan, 'Luis W. Alvarez, Nobel Physicist Who Explored Atom, Dies at 77: Obituary', New York Times (2 Sep 1988).

[Magic] enables man to carry out with confidence his important tasks, to maintain his poise and his mental integrity in fits of anger, in the throes of hate, of unrequited love, of despair and anxiety. The function of magic is to ritualize man's optimism, to enhance his faith in the victory of hope over fear. Magic expresses the greater value for man of confidence over doubt, of steadfastness over vacillation, of optimism over pessimism.

Magic, Science and Religion (1925), 90.

[Man] … his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labour of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man's achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins…

From 'A Free Man's Worship', Independent Review (Dec 1903). Collected in Mysticism and Logic: And Other Essays (1918), 47-48.

[The problem I hope scientists will have solved by the end of the 21st century is:] The production of energy without any deleterious effects. The problem is then we’d be so powerful, there’d be no restraint and we’d continue wrecking everything. Solar energy would be preferable to nuclear. If you could harness it to produce desalination, you could make the Sahara bloom.

From 'Interview: Of Mind and Matter: David Attenborough Meets Richard Dawkins', The Guardian (11 Sep 2010).

[The problem I hope scientists will have solved by the end of the 21st century] thinking more academically: the problem of human consciousness.

From 'Interview: Of Mind and Matter: David Attenborough Meets Richard Dawkins', The Guardian (11 Sep 2010).

Strictly Germ-proof

The Antiseptic Baby and the Prophylactic Pup

Were playing in the garden when the Bunny gamboled up;

They looked upon the Creature with a loathing undisguised;—

It wasn't Disinfected and it wasn't Sterilized.

They said it was a Microbe and a Hotbed of Disease;

They steamed it in a vapor of a thousand-odd degrees;

They froze it in a freezer that was cold as Banished Hope

And washed it in permanganate with carbolated soap.

In sulphurated hydrogen they steeped its wiggly ears;

They trimmed its frisky whiskers with a pair of hard-boiled shears;

They donned their rubber mittens and they took it by the hand

And elected it a member of the Fumigated Band.

There's not a Micrococcus in the garden where they play;

They bathe in pure iodoform a dozen times a day;

And each imbibes his rations from a Hygienic Cup—

The Bunny and the Baby and the Prophylactic Pup.

The Antiseptic Baby and the Prophylactic Pup

Were playing in the garden when the Bunny gamboled up;

They looked upon the Creature with a loathing undisguised;—

It wasn't Disinfected and it wasn't Sterilized.

They said it was a Microbe and a Hotbed of Disease;

They steamed it in a vapor of a thousand-odd degrees;

They froze it in a freezer that was cold as Banished Hope

And washed it in permanganate with carbolated soap.

In sulphurated hydrogen they steeped its wiggly ears;

They trimmed its frisky whiskers with a pair of hard-boiled shears;

They donned their rubber mittens and they took it by the hand

And elected it a member of the Fumigated Band.

There's not a Micrococcus in the garden where they play;

They bathe in pure iodoform a dozen times a day;

And each imbibes his rations from a Hygienic Cup—

The Bunny and the Baby and the Prophylactic Pup.

Printed in various magazines and medical journals, for example, The Christian Register (11 Oct 1906), 1148, citing Women's Home Companion. (Making fun of the contemporary national passion for sanitation.)

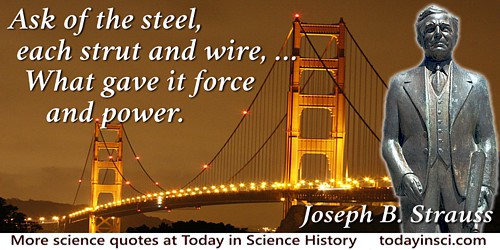

The Mighty Task is Done

At last the mighty task is done;

Resplendent in the western sun

The Bridge looms mountain high;

Its titan piers grip ocean floor,

Its great steel arms link shore with shore,

Its towers pierce the sky.

On its broad decks in rightful pride,

The world in swift parade shall ride,

Throughout all time to be;

Beneath, fleet ships from every port,

Vast landlocked bay, historic fort,

And dwarfing all the sea.

To north, the Redwood Empires gates;

To south, a happy playground waits,

In Rapturous appeal;

Here nature, free since time began,

Yields to the restless moods of man,

Accepts his bonds of steel.

Launched midst a thousand hopes and fears,

Damned by a thousand hostile sneers,

Yet Neer its course was stayed,

But ask of those who met the foe

Who stood alone when faith was low,

Ask them the price they paid.

Ask of the steel, each strut and wire,

Ask of the searching, purging fire,

That marked their natal hour;

Ask of the mind, the hand, the heart,

Ask of each single, stalwart part,

What gave it force and power.

An Honored cause and nobly fought

And that which they so bravely wrought,

Now glorifies their deed,

No selfish urge shall stain its life,

Nor envy, greed, intrigue, nor strife,

Nor false, ignoble creed.

High overhead its lights shall gleam,

Far, far below lifes restless stream,

Unceasingly shall flow;

For this was spun its lithe fine form,

To fear not war, nor time, nor storm,

For Fate had meant it so.

At last the mighty task is done;

Resplendent in the western sun

The Bridge looms mountain high;

Its titan piers grip ocean floor,

Its great steel arms link shore with shore,

Its towers pierce the sky.

On its broad decks in rightful pride,

The world in swift parade shall ride,

Throughout all time to be;

Beneath, fleet ships from every port,

Vast landlocked bay, historic fort,

And dwarfing all the sea.

To north, the Redwood Empires gates;

To south, a happy playground waits,

In Rapturous appeal;

Here nature, free since time began,

Yields to the restless moods of man,

Accepts his bonds of steel.

Launched midst a thousand hopes and fears,

Damned by a thousand hostile sneers,

Yet Neer its course was stayed,

But ask of those who met the foe

Who stood alone when faith was low,

Ask them the price they paid.

Ask of the steel, each strut and wire,

Ask of the searching, purging fire,

That marked their natal hour;

Ask of the mind, the hand, the heart,

Ask of each single, stalwart part,

What gave it force and power.

An Honored cause and nobly fought

And that which they so bravely wrought,

Now glorifies their deed,

No selfish urge shall stain its life,

Nor envy, greed, intrigue, nor strife,

Nor false, ignoble creed.

High overhead its lights shall gleam,

Far, far below lifes restless stream,

Unceasingly shall flow;

For this was spun its lithe fine form,

To fear not war, nor time, nor storm,

For Fate had meant it so.

Written upon completion of the building of the Golden Gate Bridge, May 1937. In Allen Brown, Golden Gate: biography of a Bridge (1965), 229.

[About Sir Roderick Impey Murchison:] The enjoyments of elegant life you early chose to abandon, preferring to wander for many successive years over the rudest portions of Europe and Asia—regions new to Science—in the hope, happily realized, of winning new truths.

By a rare union of favourable circumstances, and of personal qualifications equally rare, you have thus been enabled to become the recognized Interpreter and Historian (not without illustrious aid) of the Silurian Period.

By a rare union of favourable circumstances, and of personal qualifications equally rare, you have thus been enabled to become the recognized Interpreter and Historian (not without illustrious aid) of the Silurian Period.

Dedication page in Thesaurus Siluricus: The Flora and Fauna of the Silurian Period (1868), iv.

[Describing the effects of over-indulgence in wine:]

But most too passive, when the blood runs low

Too weakly indolent to strive with pain,

And bravely by resisting conquer fate,

Try Circe's arts; and in the tempting bowl

Of poisoned nectar sweet oblivion swill.

Struck by the powerful charm, the gloom dissolves

In empty air; Elysium opens round,

A pleasing frenzy buoys the lightened soul,

And sanguine hopes dispel your fleeting care;

And what was difficult, and what was dire,

Yields to your prowess and superior stars:

The happiest you of all that e'er were mad,

Or are, or shall be, could this folly last.

But soon your heaven is gone: a heavier gloom

Shuts o'er your head; and, as the thundering stream,

Swollen o'er its banks with sudden mountain rain,

Sinks from its tumult to a silent brook,

So, when the frantic raptures in your breast

Subside, you languish into mortal man;

You sleep, and waking find yourself undone,

For, prodigal of life, in one rash night

You lavished more than might support three days.

A heavy morning comes; your cares return

With tenfold rage. An anxious stomach well

May be endured; so may the throbbing head;

But such a dim delirium, such a dream,

Involves you; such a dastardly despair

Unmans your soul, as maddening Pentheus felt,

When, baited round Citheron's cruel sides,

He saw two suns, and double Thebes ascend.

But most too passive, when the blood runs low

Too weakly indolent to strive with pain,

And bravely by resisting conquer fate,

Try Circe's arts; and in the tempting bowl

Of poisoned nectar sweet oblivion swill.

Struck by the powerful charm, the gloom dissolves

In empty air; Elysium opens round,

A pleasing frenzy buoys the lightened soul,

And sanguine hopes dispel your fleeting care;

And what was difficult, and what was dire,

Yields to your prowess and superior stars:

The happiest you of all that e'er were mad,

Or are, or shall be, could this folly last.

But soon your heaven is gone: a heavier gloom

Shuts o'er your head; and, as the thundering stream,

Swollen o'er its banks with sudden mountain rain,

Sinks from its tumult to a silent brook,

So, when the frantic raptures in your breast

Subside, you languish into mortal man;

You sleep, and waking find yourself undone,

For, prodigal of life, in one rash night

You lavished more than might support three days.

A heavy morning comes; your cares return

With tenfold rage. An anxious stomach well

May be endured; so may the throbbing head;

But such a dim delirium, such a dream,

Involves you; such a dastardly despair

Unmans your soul, as maddening Pentheus felt,

When, baited round Citheron's cruel sides,

He saw two suns, and double Thebes ascend.

The Art of Preserving Health: a Poem in Four Books (2nd. ed., 1745), Book IV, 108-110.

Between the frontiers of the three super-states Eurasia, Oceania, and Eastasia, and not permanently in possession of any of them, there lies a rough quadrilateral with its corners at Tangier, Brazzaville, Darwin, and Hongkong. These territories contain a bottomless reserve of cheap labour. Whichever power controls equatorial Africa, or the Middle East or Southern India or the Indonesian Archipelago, disposes also of the bodies of hundreds of millions of ill-paid and hardworking coolies, expended by their conquerors like so much coal or oil in the race to turn out more armaments, to capture more territory, to control more labour, to turn out more armaments, to capture more territory, to control…

Thus George Orwell—in his only reference to the less-developed world.

I wish I could disagree with him. Orwell may have erred in not anticipating the withering of direct colonial controls within the “quadrilateral” he speaks about; he may not quite have gauged the vehemence of urges to political self-assertion. Nor, dare I hope, was he right in the sombre picture of conscious and heartless exploitation he has painted. But he did not err in predicting persisting poverty and hunger and overcrowding in 1984 among the less privileged nations.

I would like to live to regret my words but twenty years from now, I am positive, the less-developed world will be as hungry, as relatively undeveloped, and as desperately poor, as today.

Thus George Orwell—in his only reference to the less-developed world.

I wish I could disagree with him. Orwell may have erred in not anticipating the withering of direct colonial controls within the “quadrilateral” he speaks about; he may not quite have gauged the vehemence of urges to political self-assertion. Nor, dare I hope, was he right in the sombre picture of conscious and heartless exploitation he has painted. But he did not err in predicting persisting poverty and hunger and overcrowding in 1984 among the less privileged nations.

I would like to live to regret my words but twenty years from now, I am positive, the less-developed world will be as hungry, as relatively undeveloped, and as desperately poor, as today.

'The Less-Developed World: How Can We be Optimists?' (1964). Reprinted in Ideals and Realities (1984), xv-xvi. Referencing a misquote from George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty Four (1949), Ch. 9.

Boss: Dilbert, You have been chosen to design the world’s safest nuclear power plant.

Dilbert: This is the great assignment that any engineer could hope for. I'm flattered by the trust you have in me.

Boss: By “safe” I mean “not near my house.”

Dilbert: This is the great assignment that any engineer could hope for. I'm flattered by the trust you have in me.

Boss: By “safe” I mean “not near my house.”

Dilbert comic strip (18 Feb 2002).

Dogbert (advice to Boss): Every credible scientist on earth says your products harm the environment. I recommend paying weasels to write articles casting doubt on the data. Then eat the wrong kind of foods and hope you die before the earth does.

Dilbert cartoon strip (30 Oct 2007).

Et j’espère que nos neveux me sauront gré, non seulement des choses que j'ai ici expliquées, mais aussi de celles que j'ai omises volontairement, afin de leur laisser le plaisir de les inventer.

I hope that posterity will judge me kindly, not only as to the things which I have explained, but also as to those which I have intentionally omitted so as to leave to others the pleasure of discovery.

I hope that posterity will judge me kindly, not only as to the things which I have explained, but also as to those which I have intentionally omitted so as to leave to others the pleasure of discovery.

Concluding remark in Géométrie (1637), as translated by David Eugene Smith and Marcia L. Latham, in The Geometry of René Descartes (1925, 1954), 240.

Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch'entrate.

Abandon all hope ye who enter here.

Abandon all hope ye who enter here.

From La Divina Commedia, in 'The Gate of Hell', Inferno (1308-1321), Canto III.

~~[Misattributed; NOT by Collins]~~ Hypochondriacs squander large sums of time in search of nostrums by which they vainly hope they may get more time to squander.

This appears in Charles Caleb Colton, Lacon: Or Many Things in Few Words, Addressed to Those who Think (1823), Vol. 1, 99. Since Mortimer Collins was born in 1827, four years after the Colton publication, Collins cannot be the author. Nevertheless, it is widely seen misattributed to Collins, for example in Peter McDonald (ed.), Oxford Dictionary of Medical Quotations (2004), 27. Even seen attributed to Peter Ouspensky (born 1878), in Encarta Book of Quotations (2000). See the Charles Caleb Colton Quotes page on this website. The quote appears on this page to include it with this caution of misattribution.

A common fallacy in much of the adverse criticism to which science is subjected today is that it claims certainty, infallibility and complete emotional objectivity. It would be more nearly true to say that it is based upon wonder, adventure and hope.

Quoted in E. J. Bowen's obituary of Hinshelwood, Chemistry in Britain (1967), Vol. 3, 536.

A few of the results of my activities as a scientist have become embedded in the very texture of the science I tried to serve—this is the immortality that every scientist hopes for. I have enjoyed the privilege, as a university teacher, of being in a position to influence the thought of many hundreds of young people and in them and in their lives I shall continue to live vicariously for a while. All the things I care for will continue for they will be served by those who come after me. I find great pleasure in the thought that those who stand on my shoulders will see much farther than I did in my time. What more could any man want?

In 'The Meaning of Death,' in The Humanist Outlook edited by A. J. Ayer (1968) [See Gerald Holton and Sir Isaac Newton].

A great man, [who] was convinced that the truths of political and moral science are capable of the same certainty as those that form the system of physical science, even in those branches like astronomy that seem to approximate mathematical certainty.

He cherished this belief, for it led to the consoling hope that humanity would inevitably make progress toward a state of happiness and improved character even as it has already done in its knowledge of the truth.

He cherished this belief, for it led to the consoling hope that humanity would inevitably make progress toward a state of happiness and improved character even as it has already done in its knowledge of the truth.

Describing administrator and economist Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot in Essai sur l’application de l’analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix (1785), i. Cited epigraph in Charles Coulston Gillispie, Science and Polity in France: The End of the Old Regime (2004), 3

A hundred years ago, the electric telegraph made possible—indeed, inevitable—the United States of America. The communications satellite will make equally inevitable a United Nations of Earth; let us hope that the transition period will not be equally bloody.

Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, Edwin E. Aldrin et al., First on the Moon (1970), 389.

A large proportion of mankind, like pigeons and partridges, on reaching maturity, having passed through a period of playfulness or promiscuity, establish what they hope and expect will be a permanent and fertile mating relationship. This we call marriage.

Genetics And Man (1964), 298.

A million million spermatozoa,

All of them alive:

Out of their cataclysm but one poor Noah

Dare hope to survive.

And among that billion minus one

Might have chanced to be Shakespeare, another Newton, a new Donne—

But the One was Me.

All of them alive:

Out of their cataclysm but one poor Noah

Dare hope to survive.

And among that billion minus one

Might have chanced to be Shakespeare, another Newton, a new Donne—

But the One was Me.

'Fifth Philosopher's Song', Leda (1920),33.

A modern branch of mathematics, having achieved the art of dealing with the infinitely small, can now yield solutions in other more complex problems of motion, which used to appear insoluble. This modern branch of mathematics, unknown to the ancients, when dealing with problems of motion, admits the conception of the infinitely small, and so conforms to the chief condition of motion (absolute continuity) and thereby corrects the inevitable error which the human mind cannot avoid when dealing with separate elements of motion instead of examining continuous motion. In seeking the laws of historical movement just the same thing happens. The movement of humanity, arising as it does from innumerable human wills, is continuous. To understand the laws of this continuous movement is the aim of history. … Only by taking an infinitesimally small unit for observation (the differential of history, that is, the individual tendencies of man) and attaining to the art of integrating them (that is, finding the sum of these infinitesimals) can we hope to arrive at the laws of history.

War and Peace (1869), Book 11, Chap. 1.

A theory is a supposition which we hope to be true, a hypothesis is a supposition which we expect to be useful; fictions belong to the realm of art; if made to intrude elsewhere, they become either make-believes or mistakes.

As quoted by William Ramsay, in 'Radium and Its Products', Harper’s Magazine (Dec 1904), 52. The first part, about suppositions, appears in a paper read by G. Johnson Stoney to the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (3 Apr 1903), printed in 'On the Dependence of What Apparently Takes Place in Nature Upon What Actually Occurs in the Universe of Real Existences', Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge (Apr-May 1903) 42, No. 173, 107. If you know a primary source for the part on fictions and mistakes, please contact Webmaster.

After five years' work I allowed myself to speculate on the subject, and drew up some short notes; these I enlarged in 1844 into a sketch of the conclusions, which then seemed to me probable: from that period to the present day I have steadily pursued the same object. I hope that I may be excused for entering on these personal details, as I give them to show that I have not been hasty in coming to a decision.

From On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection; or, The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1861), 9.

All talk about science purely for its practical and wealth-producing results is … idle. … Practical results will follow right enough. No real knowledge is sterile. … With this faith in the ultimate usefulness of all real knowledge a man may proceed to devote himself to a study of first causes without apology, and without hope of immediate return.

Quoted in Larry R. Squire (ed.), The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography (1996), Vol. 1, 350-351. The above is a highlight excerpted from a longer quote beginning “To prove to an indignant questioner ….” in this same collection for A. V. Hill.

All that Anatomie can doe is only to shew us the gross and sensible parts of the body, or the vapid and dead juices all which, after the most diligent search, will be noe more able to direct a physician how to cure a disease than how to make a man; for to remedy the defects of a part whose organicall constitution and that texture whereby it operates, he cannot possibly know, is alike hard, as to make a part which he knows not how is made. Now it is certaine and beyond controversy that nature performs all her operations on the body by parts so minute and insensible that I thinke noe body will ever hope or pretend, even by the assistance of glasses or any other intervention, to come to a sight of them, and to tell us what organicall texture or what kinde offerment (for whether it be done by one or both of these ways is yet a question and like to be soe always notwithstanding all the endeavours of the most accurate dissections) separate any part of the juices in any of the viscera, or tell us of what liquors the particles of these juices are, or if this could be donne (which it is never like to be) would it at all contribute to the cure of the diseases of those very parts which we so perfectly knew.

'Anatomie' (1668). Quoted in Kenneth Dewhurst (ed.), Dr. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689): His Life and Original Writings (1966), 85-6.

All that we can hope from these inspirations, which are the fruits of unconscious work, is to obtain points of departure for such calculations. As for the calculations themselves, they must be made in the second period of conscious work which follows the inspiration, and in which the results of the inspiration are verified and the consequences deduced.

Science and Method (1914, 2003), 62.

Always be suspicious of conclusions that reinforce uncritical hope and follow comforting traditions of Western thought.

From The Flamingo's Smile (1987), 401.

And so, after many years, victory has come, and the romance of exploration, of high hopes and bitter disappointment, will in a few years simply be recorded in the text-books of organic chemistry in a few terse sentences.

Recent Developments in the Vitamin A Field', The Pedlar Lecture, 4 Dec 1947, Journal of the Chemical Society, Part I (1948), 393.

Another argument of hope may be drawn from this–that some of the inventions already known are such as before they were discovered it could hardly have entered any man's head to think of; they would have been simply set aside as impossible. For in conjecturing what may be men set before them the example of what has been, and divine of the new with an imagination preoccupied and colored by the old; which way of forming opinions is very fallacious, for streams that are drawn from the springheads of nature do not always run in the old channels.

Translation of Novum Organum, XCII. In Francis Bacon, James Spedding, The Works of Francis Bacon (1864), Vol. 8, 128.

Anthropology has reached that point of development where the careful investigation of facts shakes our firm belief in the far-reaching theories that have been built up. The complexity of each phenomenon dawns on our minds, and makes us desirous of proceeding more cautiously. Heretofore we have seen the features common to all human thought. Now we begin to see their differences. We recognize that these are no less important than their similarities, and the value of detailed studies becomes apparent. Our aim has not changed, but our method must change. We are still searching for the laws that govern the growth of human culture, of human thought; but we recognize the fact that before we seek for what is common to all culture, we must analyze each culture by careful and exact methods, as the geologist analyzes the succession and order of deposits, as the biologist examines the forms of living matter. We see that the growth of human culture manifests itself in the growth of each special culture. Thus we have come to understand that before we can build up the theory of the growth of all human culture, we must know the growth of cultures that we find here and there among the most primitive tribes of the Arctic, of the deserts of Australia, and of the impenetrable forests of South America; and the progress of the civilization of antiquity and of our own times. We must, so far as we can, reconstruct the actual history of mankind, before we can hope to discover the laws underlying that history.

The Jesup North Pacific Expedition: Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History (1898), Vol. 1, 4.

Arithmetic is where you have to multiply—and you carry the multiplication table in your head and hope you won’t lose it.

From 'Arithmetic', Harvest Poems, 1910-1960 (1960), 116.

As each bit of information is added to the sum of human knowledge it is evident that it is the little things that count; that give all the fertility and character; that give all the hope and happiness to human affairs. The concept of bigness is apt to be a delusion, and standardizing processes must not supplant creative impulses.

In Nobel Banquet speech (10 Dec 1934). Collected in Gustaf Santesson (ed.) Les Prix Nobel en 1934 (1935).

As evolutionary time is measured, we have only just turned up and have hardly had time to catch breath, still marveling at our thumbs, still learning to use the brand-new gift of language. Being so young, we can be excused all sorts of folly and can permit ourselves the hope that someday, as a species, we will begin to grow up.

From 'Introduction' written by Lewis Thomas for Horace Freeland Judson, The Search for Solutions (1980, 1987), xvii.

As I had occasion to pass daily to and from the building-yard, while my boat was in progress, I have often loitered unknown near the idle groups of strangers, gathering in little circles, and heard various inquiries as to the object of this new vehicle. The language was uniformly that of scorn, or sneer, or ridicule. The loud laugh often rose at my expense; the dry jest; the wise calculation of losses and expenditures; the dull, but endless, repetition of “the Fulton folly”. Never did a single encouraging remark, a bright hope, or a warm wish, cross my path.

As quoted in Kirkpatrick Sale, The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream (2001), 10. Citing in end notes as from Story, Life and Letters, 24.

As the vernal equinox heralds the arrival of spring, it symbolizes not only the rebirth of nature but also the renewal of hope and possibility in our lives.

A fictional quote imagined in the style typical of a scientist (19 Mar 2024).

As we discern a fine line between crank and genius, so also (and unfortunately) we must acknowledge an equally graded trajectory from crank to demagogue. When people learn no tools of judgment and merely follow their hopes, the seeds of political manipulation are sown.

…...

As we look ahead through the vista of science with its tremendous possibilities for progress in peacetime, let us not feel that we are looking beyond the horizon of hope. The outlook is not discouraging, for there is no limit to man’s ingenuity and no end to the opportunities for progress.

In address (Fall 1946) at a dinner in New York to commemorate the 40 years of Sarnoff’s service in the radio field, 'Institute News and Radio Notes: The Past and Future of Radio', Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers (I.R.E.), (May 1947), 35, No. 5, 498.

At terrestrial temperatures matter has complex properties which are likely to prove most difficult to unravel; but it is reasonable to hope that in the not too distant future we shall be competent to understand so simple a thing as a star.

The Internal Constitution of Stars, Cambridge. (1926, 1988), 393.

Basic research is not the same as development. A crash program for the latter may be successful; but for the former it is like trying to make nine women pregnant at once in the hope of getting a baby in a month’s time.

In New Scientist, November 18, 1976.

Beasts have not the high advantages which we possess; but they have some which we have not. They have not our hopes, but then they have not our fears; they are subject like us to death, but it is without being aware of it; most of them are better able to preserve themselves than we are, and make a less bad use of their passions.

In Edwin Davies, Other Men's Minds, Or, Seven Thousand Choice Extracts (1800), 55.

Before his [Sir Astley Cooper’s] time, operations were too often frightful alternatives or hazardous compromises; and they were not seldom considered rather as the resource of despair than as a means of remedy; he always made them follow, as it were, in the natural course of treatment; he gave them a scientific character; and he moreover, succeeded, in a great degree, in divesting them of their terrors, by performing them unostentatiously, simply, confidently, and cheerfully, and thereby inspiring the patient with hope of relief, where previously resignation under misfortune had too often been all that could be expected from the sufferer.

In John Forbes (ed.), British and Foreign Medical Review (Jul 1840), 10, No. 19, 104. In Bransby Blake Cooper, The Life of Sir Astley Cooper (1843), Vol. 2, 37.

Before Kuhn, most scientists followed the place-a-stone-in-the-bright-temple-of-knowledge tradition, and would have told you that they hoped, above all, to lay many of the bricks, perhaps even the keystone, of truth’s temple. Now most scientists of vision hope to foment revolution. We are, therefore, awash in revolutions, most self-proclaimed.

…...

Beware how you take away hope from any human being. Nothing is clearer than that the merciful Creator intends to blind most people as they pass down into the dark valley. Without very good reasons, temporal or spiritual, we should not interfere with his kind arrangements. It is the height of cruelty and the extreme of impertinence to tell your patient he must die, except you are sure that he wishes to know it, or that there is some particular cause for his knowing it. I should be especially unwilling to tell a child that it could not recover; if the theologians think it necessary, let them take the responsibility. God leads it by the hand to the edge of the precipice in happy unconsciousness, and I would not open its eyes to what he wisely conceals.

In Valedictory Address Delivered to the Medical Graduates at Harvard University, at the Annual Commencement, Wednesday, March 10, 1858) (1858), 14. Reprinted, as published in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (25 Mar 1858), 58, No. 8, 158.

By a recent estimate, nearly half the bills before the U.S. Congress have a substantial science-technology component and some two-thirds of the District of Columbia Circuit Court’s case load now involves review of action by federal administrative agencies; and more and more of such cases relate to matters on the frontiers of technology.

If the layman cannot participate in decision making, he will have to turn himself over, essentially blind, to a hermetic elite. … [The fundamental question becomes] are we still capable of self-government and therefore freedom?

Margaret Mead wrote in a 1959 issue of Daedalus about scientists elevated to the status of priests. Now there is a name for this elevation, when you are in the hands of—one hopes—a benevolent elite, when you have no control over your political decisions. From the point of view of John Locke, the name for this is slavery.

If the layman cannot participate in decision making, he will have to turn himself over, essentially blind, to a hermetic elite. … [The fundamental question becomes] are we still capable of self-government and therefore freedom?

Margaret Mead wrote in a 1959 issue of Daedalus about scientists elevated to the status of priests. Now there is a name for this elevation, when you are in the hands of—one hopes—a benevolent elite, when you have no control over your political decisions. From the point of view of John Locke, the name for this is slavery.

Quoted in 'Where is Science Taking Us? Gerald Holton Maps the Possible Routes', The Chronicle of Higher Education (18 May 1981). In Francis A. Schaeffer, A Christian Manifesto (1982), 80.

Charlie Holloway (human): “What we hoped to achieve was to meet our makers. To get answers. Why they even made us in the first place.”

David (AI robot): “Why do you think your people made me?”

Charlie Holloway (human): “We made you because we could.”

David (AI robot): “Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?”

Charlie Holloway (human): “I guess it’s good you can’t be disappointed.”

David (AI robot): “Why do you think your people made me?”

Charlie Holloway (human): “We made you because we could.”

David (AI robot): “Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?”

Charlie Holloway (human): “I guess it’s good you can’t be disappointed.”

Prometheus (2012)

Considerable obstacles generally present themselves to the beginner, in studying the elements of Solid Geometry, from the practice which has hitherto uniformly prevailed in this country, of never submitting to the eye of the student, the figures on whose properties he is reasoning, but of drawing perspective representations of them upon a plane. ...I hope that I shall never be obliged to have recourse to a perspective drawing of any figure whose parts are not in the same plane.

Quoted in Adrian Rice, 'What Makes a Great Mathematics Teacher?' The American Mathematical Monthly, (June-July 1999), 540.

Courage is like love; it must have hope to nourish it.

…...

Creativity comes from trust. Trust your instincts. And never hope more than you work.

In Starting From Scratch: A Different Kind of Writers’ Manual (1988), xi.

Darwin grasped the philosophical bleakness with his characteristic courage. He argued that hope and morality cannot, and should not, be passively read in the construction of nature. Aesthetic and moral truths, as human concepts, must be shaped in human terms, not ‘discovered’ in nature. We must formulate these answers for ourselves and then approach nature as a partner who can answer other kinds of questions for us–questions about the factual state of the universe, not about the meaning of human life. If we grant nature the independence of her own domain–her answers unframed in human terms–then we can grasp her exquisite beauty in a free and humble way. For then we become liberated to approach nature without the burden of an inappropriate and impossible quest for moral messages to assuage our hopes and fears. We can pay our proper respect to nature’s independence and read her own ways as beauty or inspiration in our different terms.

…...

Descended from the apes? My dear, we will hope it is not true. But if it is, let us pray that it may not become generally known.

Remark by the wife of a canon of Worcester Cathedral. Quoted in Ashley Montagu, Manʹs Most Dangerous Myth: the Fallacy of Race (1945), 27.

Despair is better treated with hope, not dope.

Lancet (1958), 1, 954.

Education has, thus, become the chief problem of the world, its one holy cause. The nations that see this will survive, and those that fail to do so will slowly perish. There must be re-education of the will and of the heart as well as of the intellect, and the ideals of service must supplant those of selfishness and greed. ... Never so much as now is education the one and chief hope of the world.

Confessions of a Psychologist (1923). Quoted in Bruce A. Kimball, The True Professional Ideal in America: A History (1996), 198.

Education is the most sacred concern, indeed the only hope, of a nation.

In paper 'On Social Unrest', The Daily Mail (1912). Collected and cited in A Sheaf (1916), 198.

England and all civilised nations stand in deadly peril of not having enough to eat. As mouths multiply, food resources dwindle. Land is a limited quantity, and the land that will grow wheat is absolutely dependent on difficult and capricious natural phenomena... I hope to point a way out of the colossal dilemma. It is the chemist who must come to the rescue of the threatened communities. It is through the laboratory that starvation may ultimately be turned into plenty... The fixation of atmospheric nitrogen is one of the great discoveries, awaiting the genius of chemists.

Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1898. Published in Chemical News, 1898, 78, 125.

Every appearance in nature corresponds to some state of the mind, and that state of the mind can only be described by presenting that natural appearance as its picture. An enraged man is a lion, a cunning man is a fox, a firm man is a rock, a learned man is a torch. A lamb is innocence; a snake is subtle spite; flowers express to us the delicate affections. Light and darkness are our familiar expressions for knowledge and ignorance ; and heat for love. Visible distance behind and before us, is respectively our image of memory and hope.

In essay, 'Language', collected in Nature: An Essay ; And, Lectures on the Times (1844), 23-24.

Every generation has the right to build its own world out of the materials of the past, cemented by the hopes of the future.

Speech, Republican National Convention, Chicago (27 Jun 1944), 'Freedom in America and the World', collected in Addresses Upon the American Road: 1941-1945 (1946), 254.

Every thoughtful man who hopes for the creation of a contemporary culture knows that this hinges on one central problem: to find a coherent relation between science and the humanities.

With co-author Bruce Mazlish, in The Western Intellectual Tradition (1960).

Everything material which is the subject of knowledge has number, order, or position; and these are her first outlines for a sketch of the universe. If our feeble hands cannot follow out the details, still her part has been drawn with an unerring pen, and her work cannot be gainsaid. So wide is the range of mathematical sciences, so indefinitely may it extend beyond our actual powers of manipulation that at some moments we are inclined to fall down with even more than reverence before her majestic presence. But so strictly limited are her promises and powers, about so much that we might wish to know does she offer no information whatever, that at other moments we are fain to call her results but a vain thing, and to reject them as a stone where we had asked for bread. If one aspect of the subject encourages our hopes, so does the other tend to chasten our desires, and he is perhaps the wisest, and in the long run the happiest, among his fellows, who has learned not only this science, but also the larger lesson which it directly teaches, namely, to temper our aspirations to that which is possible, to moderate our desires to that which is attainable, to restrict our hopes to that of which accomplishment, if not immediately practicable, is at least distinctly within the range of conception.

From Presidential Address (Aug 1878) to the British Association, Dublin, published in the Report of the 48th Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1878), 31.

Evil communication corrupts good manners. I hope to live to hear that good communication corrects bad manners.

On a leaf of one of Banneker’s almanacs, in his own handwriting. As quoted in George Washington Williams, History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880 (1882), Vol. 1, 390.

Finally one should add that in spite of the great complexity of protein synthesis and in spite of the considerable technical difficulties in synthesizing polynucleotides with defined sequences it is not unreasonable to hope that all these points will be clarified in the near future, and that the genetic code will be completely established on a sound experimental basis within a few years.

From Nobel Lecture (11 Dec 1962), 'On the Genetic Code'. Collected in Nobel Lectures: Physiology or Medicine 1942-1962 (1964), 808.

Firm support has been found for the assertion that electricity occurs at thousands of points where we at most conjectured that it was present. Innumerable electrical particles oscillate in every flame and light source. We can in fact assume that every heat source is filled with electrons which will continue to oscillate ceaselessly and indefinitely. All these electrons leave their impression on the emitted rays. We can hope that experimental study of the radiation phenomena, which are exposed to various influences, but in particular to the effect of magnetism, will provide us with useful data concerning a new field, that of atomistic astronomy, as Lodge called it, populated with atoms and electrons instead of planets and worlds.

'Light Radiation in a Magnetic Field', Nobel Lecture, 2 May 1903. In Nobel Lectures: Physics 1901-1921 (1967), 40.

Five centuries ago the printing press sparked a radical reshaping of the nature of education. By bringing a master’s words to those who could not hear a master’s voice, the technology of printing dissolved the notion that education must be reserved for those with the means to hire personal tutors. Today we are approaching a new technological revolution, one whose impact on education may be as far-reaching as that of the printing press: the emergence of powerful computers that are sufficiently inexpensive to be used by students for learning, play and exploration. It is our hope that these powerful but simple tools for creating and exploring richly interactive environments will dissolve the barriers to the production of knowledge as the printing press dissolved the barriers to its transmission.

As co-author with A.A. diSessa, from 'Preface', Turtle Geometry: The Computer as a Medium for Exploring Mathematics (1986), xiii.

Following the example of Archimedes who wished his tomb decorated with his most beautiful discovery in geometry and ordered it inscribed with a cylinder circumscribed by a sphere, James Bernoulli requested that his tomb be inscribed with his logarithmic spiral together with the words, “Eadem mutata resurgo,” a happy allusion to the hope of the Christians, which is in a way symbolized by the properties of that curve.

From 'Eloge de M. Bernoulli', Oeuvres de Fontenelle, t. 5 (1768), 112. As translated in Robert Édouard Moritz, Memorabilia Mathematica; Or, The Philomath’s Quotation-Book (1914), 143-144. [The Latin phrase, Eadem numero mutata resurgo means as “Though changed, I arise again exactly the same”. —Webmaster]

For any one who is pervaded with the sense of causal law in all that happens, who accepts in real earnest the assumption of causality, the idea of a Being who interferes with the sequence of events in the world is absolutely impossible! Neither the religion of fear nor the social-moral religion can have, any hold on him. A God who rewards and punishes is for him unthinkable, because man acts in accordance with an inner and outer necessity, and would, in the eyes of God, be as little responsible as an inanimate object is for the movements which it makes. Science, in consequence, has been accused of undermining morals—but wrongly. The ethical behavior of man is better based on sympathy, education and social relationships, and requires no support from religion. Man’s plight would, indeed, be sad if he had to be kept in order through fear of punishment and hope of rewards after death.

From 'Religion and Science', The New York Times Magazine, (9 Nov 1930), 1. Article in full, reprinted in Edward H. Cotton (ed.), Has Science Discovered God? A Symposium of Modern Scientific Opinion (1931), 101. The wording differs significantly from the version collected in 'Religion And Science', Ideas And Opinions (1954), 39, giving its source as: “Written expressly for the New York Times Magazine. Appeared there November 9, 1930 (pp. 1-4). The German text was published in the Berliner Tageblatt, November 11, 1930.” This variant form of the quote from the book begins, “The man who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation….” and is also on the Albert Einstein Quotes page on this website. As for why the difference, Webmaster speculates the book form editor perhaps used a revised translation from Einstein’s German article.

For forty-nine months between 1968 and 1972, two dozen Americans had the great good fortune to briefly visit the Moon. Half of us became the first emissaries from Earth to tread its dusty surface. We who did so were privileged to represent the hopes and dreams of all humanity. For mankind it was a giant leap for a species that evolved from the Stone Age to create sophisticated rockets and spacecraft that made a Moon landing possible. For one crowning moment, we were creatures of the cosmic ocean, an epoch that a thousand years hence may be seen as the signature of our century.

…...

For if as scientists we seek simplicity, then obviously we try the simplest surviving theory first, and retreat from it only when it proves false. Not this course, but any other, requires explanation. If you want to go somewhere quickly, and several alternate routes are equally likely to be open, no one asks why you take the shortest. The simplest theory is to be chosen not because it is the most likely to be true but because it is scientifically the most rewarding among equally likely alternatives. We aim at simplicity and hope for truth.

Problems and Projects (1972), 352.

For the environmentalists, The Space Option is the ultimate environmental solution. For the Cornucopians, it is the technological fix that they are relying on. For the hard core space community, the obvious by-product would be the eventual exploration and settlement of the solar system. For most of humanity however, the ultimate benefit is having a realistic hope in a future with possibilities.... If our species does not soon embrace this unique opportunity with sufficient commitment, it may miss its one and only chance to do so. Humanity could soon be overwhelmed by one or more of the many challenges it now faces. The window of opportunity is closing as fast as the population is increasing. Our future will be either a Space Age or a Stone Age.

Arthur Woods and Marco Bernasconi

For the essence of science, I would suggest, is simply the refusal to believe on the basis of hope.

In Robert Paul Wolff, Barrington Moore, Herbert Marcuse, A Critique of Pure Tolerance (1965), 55. Worded as 'Science is the refusal to believe on the basis of hope,' the quote is often seen attributed to C. P. Snow as in, for example, Richard Alan Krieger, Civilization's Quotations: Life's Ideal (2002), 314. If you know the time period or primary print source for the C.P. Snow quote, please contact Webmaster.

For the most part, statistics is a method of investigation that is used when other methods are of no avail; it is often a last resort and a forlorn hope.

In Facts from Figures (1951), 3.

FORTRAN —’the infantile disorder’—, by now nearly 20 years old, is hopelessly inadequate for whatever computer application you have in mind today: it is now too clumsy, too risky, and too expensive to use. PL/I —’the fatal disease’— belongs more to the problem set than to the solution set. It is practically impossible to teach good programming to students that have had a prior exposure to BASIC: as potential programmers they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration. The use of COBOL cripples the mind; its teaching should, therefore, be regarded as a criminal offence. APL is a mistake, carried through to perfection. It is the language of the future for the programming techniques of the past: it creates a new generation of coding bums.

…...

Gödel proved that the world of pure mathematics is inexhaustible; no finite set of axioms and rules of inference can ever encompass the whole of mathematics; given any finite set of axioms, we can find meaningful mathematical questions which the axioms leave unanswered. I hope that an analogous Situation exists in the physical world. If my view of the future is correct, it means that the world of physics and astronomy is also inexhaustible; no matter how far we go into the future, there will always be new things happening, new information coming in, new worlds to explore, a constantly expanding domain of life, consciousness, and memory.

From Lecture 1, 'Philosophy', in a series of four James Arthur Lectures, 'Lectures on Time and its Mysteries' at New York University (Autumn 1978). Printed in 'Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe', Reviews of Modern Physics (Jul 1979), 51, 449.

Grand telegraphic discovery today … Transmitted vocal sounds for the first time ... With some further modification I hope we may be enabled to distinguish … the “timbre” of the sound. Should this be so, conversation viva voce by telegraph will be a fait accompli.

Postscript (P.S.) on page 3 of letter to Sarah Fuller (1 Jul 1875). Bell Papers, Library of Congress.

He thought he saw an Argument

That proved he was the Pope:

He looked again and found it was

A Bar of Mottled Soap.

“A fact so dread.” he faintly said,

“Extinguishes all hope!”

That proved he was the Pope:

He looked again and found it was

A Bar of Mottled Soap.

“A fact so dread.” he faintly said,

“Extinguishes all hope!”

In Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893), 319.

He who has health has hope; and he who has hope has everything.

Arabic proverb.

Here is no final grieving,

but an abiding hope

The moving waters renew the earth.

It is spring.

but an abiding hope

The moving waters renew the earth.

It is spring.

Two verses from 'Sketch For a Modern Oratorio', collected in Michael Tippett and Meirion Bowen (ed.), Tippett on Music (1995), 175.

Hope being the greatest of all blessings, it is necessary, in order to be happy, to sacrifice the present to the future.

From Appendix A, 'Extracts From the Unpublished Writings of Carnot', Reflections on the Motive Power of Heat (1890, 2nd ed. 1897), 209.

Hope has as many lives as a cat or a king.

From Book III, 'A Talk on the Stairs', Hyperion: A Romance (1853), 213.

Hope is a good breakfast, but it is a bad supper.

'Apophthegms From the Resuscitatio' (1661). In Francis Bacon, James Spedding, The Works of Francis Bacon (1860), Vol. 13, 391.

Hope is a pathological belief in the occurrence of the impossible.

In A Mencken Chrestomathy (1949, 1956), 617.

Hope is a waking dream.

In Benjamin F. Powell (ed.), 'Selections Fron the Moral Remarks of Aristotle', Bible of Reason; or, Scriptures of Ancient Moralists (1837), Vol. 1, 9.

Hope is faith holding out its hands in the dark.

From chapter 'Jottings from a Note-book', in Canadian Stories (1918), 167.

Hope is the bedrock of this nation. The belief that our destiny will not be written for us, but by us, by all those men and women who are not content to settle for the world as it is, who have the courage to remake the world as it should be.

From address to supporters after the Iowa Caucuses, as provided by Congressional Quarterly via The Associated Press, published in New York Times (3 Jan 2008).

Hope is the companion of power and the mother of success, for those of us who hope strongest have within us the gift of miracles.

…...

Hopes are always accompanied by fears, and, in scientific research, the fears are liable to become dominant.

At age 67.

At age 67.

Eureka (Oct 1969), No.32, 2-4.

Hospitals are only an intermediate stage of civilization, never intended ... to take in the whole sick population. May we hope that the day will come ... when every poor sick person will have the opportunity of a share in a district sick-nurse at home.

In 'Nursing of the Sick' paper, collected in Hospitals, Dispensaries and Nursing: Papers and Discussions in the International Congress of Charities, Correction and Philanthropy, Section III, Chicago, June 12th to 17th, 1893 (1894), 457.

How can a modern anthropologist embark upon a generalization with any hope of arriving at a satisfactory conclusion? By thinking of the organizational ideas that are present in any society as a mathematical pattern.

In Rethinking Anthropology (1961), 2.

How often things occur by mere chance which we dared not even hope for.

— Terence

In Phormio, v.1, 31, as quoted and cited in (1908), 109.

How wonderful that we have met this paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.

Comment to observers when an experiment took an unexpected turn. In Bill Becker, 'Pioneer of the Atom', New York Times Sunday Magazine (20 Oct 1957), 52. Also in quoted in Ruth Moore Niels Bohr: the Man, His Science, & The World They Changed (1966), 140.

Human consciousness is just about the last surviving mystery. A mystery is a phenomenon that people don’t know how to think about—yet. There have been other great mysteries: the mystery of the origin of the universe, the mystery of life and reproduction, the mystery of the design to be found in nature, the mysteries of time, space, and gravity. These were not just areas of scientific ignorance, but of utter bafflement and wonder. We do not yet have the final answers to any of the questions of cosmology and particle physics, molecular genetics and evolutionary theory, but we do know how to think about them. The mysteries haven't vanished, but they have been tamed. They no longer overwhelm our efforts to think about the phenomena, because now we know how to tell the misbegotten questions from the right questions, and even if we turn out to be dead wrong about some of the currently accepted answers, we know how to go about looking for better answers. With consciousness, however, we are still in a terrible muddle. Consciousness stands alone today as a topic that often leaves even the most sophisticated thinkers tongue-tied and confused. And, as with all the earlier mysteries, there are many who insist—and hope—that there will never be a demystification of consciousness.

Consciousness Explained (1991), 21-22.

Hypochondriacs squander large sums of time in search of nostrums by which they vainly hope they may get more time to squander.

In Lacon: Or Many Things in Few Words, Addressed to Those who Think (1823), 99. Misattributions to authors born later than this publication include to Mortimer Collins and to Peter Ouspensky.

I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven, there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment. One is quantum electrodynamics and the other is the turbulent motion of fluids. About the former, I am really rather optimistic.

In Address to the British Society for the Advancement of Science (1932). As cited by Tom Mullin in 'Turbulent Times For FLuids', New Science (11 Nov 1989), 52. Werner Heisenberg is also reported, sometimes called apocryphal, to have expressed a similar sentiment, but Webmaster has found no specific citation.

I am certain that none of the world’s problems … have any hope of solution except through total democratic society’s becoming thoroughly … self-educated.

In Critical Path (1982), 266.

I am delighted that I have found a new reaction to demonstrate even to the blind the structure of the interstitial stroma of the cerebral cortex. I let the silver nitrate react with pieces of brain hardened in potassium dichromate. I have already obtained magnificent results and hope to do even better in the future.

Letter to Nicolo Manfredi, 16 Feb 1873. Archive source. Quoted in Paolo Mazzarello, The Hidden Structure: A Scientific Biography of Camillo Golgi, trans. and ed. Henry A. Buchtel and Aldo Badiani (1999), 63.

I believe … that we can still have a genre of scientific books suitable for and accessible alike to professionals and interested laypeople. The concepts of science, in all their richness and ambiguity, can be presented without any compromise, without any simplification counting as distortion, in language accessible to all intelligent people … I hope that this book can be read with profit both in seminars for graduate students and–if the movie stinks and you forgot your sleeping pills–on the businessman’s special to Tokyo.

In Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (1990), Preface, 16.

I believe that the laws of physics such as they are, such as they have been taught to us, are not the inevitable truth. We believe in the laws, or we experiment* with them each day, yet I believe it is possible to consider the existence of a universe in which these laws would be extended, changed a very tiny bit, in a precisely demarcated way. Consequently we immediately achieve extraordinary results, different yet certainly not far from the truth. After all, every century or two a new scientist comes along who changes the laws of physics, isn’t that so? After Newton there were many who did, and there were even more after Einstein, right? We have to wait to see how the laws in question will change over time, then… In any case, without being a scientist myself I can still hope to reach parallel results, if you will, in art.

Epigraph, in James Housefield, Playing with Earth and Sky: Astronomy, Geography, and the Art of Marcel Duchamp (2016), ix. As modified by James Housefield, from Guy Viau interview of Marcel Duchamp on Canadian Radio Television (17 July 1960), 'Simply Change Your Name', translated by Sarah Skinner Kilborne in Tout-Fait: the Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 2, no. 4 (2002). [*Note: Where the Housefield in the Epigraph uses the word “experiment”, the original French gives “expérimentons”, which in the unmodified translation by Sarah Skinner Kilborne is written more correctly as “experience.” —Webmaster]

I can certainly wish for new, large, and properly constructed instruments, and enough of them, but to state where and by what means they are to be procured, this I cannot do. Tycho Brahe has given Mastlin an instrument of metal as a present, which would be very useful if Mastlin could afford the cost of transporting it from the Baltic, and if he could hope that it would travel such a long way undamaged… . One can really ask for nothing better for the observation of the sun than an opening in a tower and a protected place underneath.

As quoted in James Bruce Ross and Mary Martin McLaughlin, The Portable Renaissance Reader (1968), 605.

I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe, and especially the nature of man, and to conclude that everything is the result of brute force. I am inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we call chance. Not that this notion at all satisfies me. I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton. Let each man hope and believe what he can.

Letter to Asa Gray (22 May 1860). In Charles Darwin and Francis Darwin (ed.), Charles Darwin: His Life Told in an Autobiographical Chapter, and in a Selected Series of His Published Letters (1892), 236.

I confess that Fermat’s Theorem as an isolated proposition has very little interest for me, for a multitude of such theorems can easily be set up, which one could neither prove nor disprove. But I have been stimulated by it to bring our again several old ideas for a great extension of the theory of numbers. Of course, this theory belongs to the things where one cannot predict to what extent one will succeed in reaching obscurely hovering distant goals. A happy star must also rule, and my situation and so manifold distracting affairs of course do not permit me to pursue such meditations as in the happy years 1796-1798 when I created the principal topics of my Disquisitiones arithmeticae. But I am convinced that if good fortune should do more than I expect, and make me successful in some advances in that theory, even the Fermat theorem will appear in it only as one of the least interesting corollaries.

In reply to Olbers' attempt in 1816 to entice him to work on Fermat's Theorem. The hope Gauss expressed for his success was never realised.

In reply to Olbers' attempt in 1816 to entice him to work on Fermat's Theorem. The hope Gauss expressed for his success was never realised.

Letter to Heinrich Olbers (21 Mar 1816). Quoted in G. Waldo Dunnington, Carl Friedrich Gauss: Titan of Science (2004), 413.

I do not hope for any relief, and that is because I have committed no crime. I might hope for and obtain pardon, if I had erred, for it is to faults that the prince can bring indulgence, whereas against one wrongfully sentenced while he was innocent, it is expedient, in order to put up a show of strict lawfulness, to uphold rigor… . But my most holy intention, how clearly would it appear if some power would bring to light the slanders, frauds, and stratagems, and trickeries that were used eighteen years ago in Rome in order to deceive the authorities!

In Letter to Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (22 Feb 1635). As quoted in translation in Giorgio de Santillana, The Crime of Galileo (1976), 324.

I do not personally want to believe that we already know the equations that determine the evolution and fate of the universe; it would make life too dull for me as a scientist. … I hope, and believe, that the Space Telescope might make the Big Bang cosmology appear incorrect to future generations, perhaps somewhat analogous to the way that Galileo’s telescope showed that the earth-centered, Ptolemaic system was inadequate.

From 'The Space Telescope (the Hubble Space Telescope): Out Where the Stars Do Not Twinkle', in NASA Authorization for Fiscal Year 1978: Hearings before the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, United States Senate, 95th Congress, first session on S.365 (1977), 124. This was testimony to support of authorization for NASA beginning the construction of the Space Telescope, which later became known as the Hubble Space Telescope.

I do not see any reason to assume that the heuristic significance of the principle of general relativity is restricted to gravitation and that the rest of physics can be dealt with separately on the basis of special relativity, with the hope that later on the whole may be fitted consistently into a general relativistic scheme. I do not think that such an attitude, although historically understandable, can be objectively justified. The comparative smallness of what we know today as gravitational effects is not a conclusive reason for ignoring the principle of general relativity in theoretical investigations of a fundamental character. In other words, I do not believe that it is justifiable to ask: What would physics look like without gravitation?

…...

I find hope in the darkest of days, and focus in the brightest. I do not judge the universe.

Quoted in Kim Lim (ed.), 1,001 Pearls of Spiritual Wisdom: Words to Enrich, Inspire, and Guide Your Life (2014), 23

I have always liked horticulturists, people who make their living from orchards and gardens, whose hands are familiar with the feel of the bark, whose eyes are trained to distinguish the different varieties, who have a form memory. Their brains are not forever dealing with vague abstractions; they are satisfied with the romance which the seasons bring with them, and have the patience and fortitude to gamble their lives and fortunes in an industry which requires infinite patience, which raise hopes each spring and too often dashes them to pieces in fall. They are always conscious of sun and wind and rain; must always be alert lest they lose the chance of ploughing at the right moment, pruning at the right time, circumventing the attacks of insects and fungus diseases by quick decision and prompt action. They are manufacturers of a high order, whose business requires not only intelligence of a practical character, but necessitates an instinct for industry which is different from that required by the city dweller always within sight of other people and the sound of their voices. The successful horticulturist spends much time alone among his trees, away from the constant chatter of human beings.

I have been arranging certain experiments in reference to the notion that Gravity itself may be practically and directly related by experiment to the other powers of matter and this morning proceeded to make them. It was almost with a feeling of awe that I went to work, for if the hope should prove well founded, how great and mighty and sublime in its hitherto unchangeable character is the force I am trying to deal with, and how large may be the new domain of knowledge that may be opened up to the mind of man.

In Thomas Martin (ed.) Faraday’s Diary: Sept. 6, 1847 - Oct. 17, 1851 (1934), 156.

I have been driven to assume for some time, especially in relation to the gases, a sort of conducting power for magnetism. Mere space is Zero. One substance being made to occupy a given portion of space will cause more lines of force to pass through that space than before, and another substance will cause less to pass. The former I now call Paramagnetic & the latter are the diamagnetic. The former need not of necessity assume a polarity of particles such as iron has with magnetic, and the latter do not assume any such polarity either direct or reverse. I do not say more to you just now because my own thoughts are only in the act of formation, but this I may say: that the atmosphere has an extraordinary magnetic constitution, & I hope & expect to find in it the cause of the annual & diurnal variations, but keep this to yourself until I have time to see what harvest will spring from my growing ideas.

Letter to William Whewell, 22 Aug 1850. In L. Pearce Williams (ed.), The Selected Correspondence of Michael Faraday (1971), Vol. 2, 589.

I hope my studies may be an encouragement to other women, especially to young women, to devote their lives to the larger interests of the mind. It matters little whether men or women have the more brains; all we women need to do to exert our proper influence is just to use all the brains we have.

In Elinor Bluemel, Florence Sabin: Colorado Woman of the Century (1959), 124. Cited elsewhere as from speech accepting the Pictorial Review achievement award (1929).

I hope my studies may be an encouragement to other women, especially to young women, to devote their lives to the larger interests of the mind. It matters little whether men or women have the more brains; all we women need to do to exert our proper influence is just to use all the brains we have."

As quoted in part, in Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948), 8. Cited more completely elsewhere as from speech accepting the Pictorial Review achievement award (1929).

I hope that in 50 years we will know the answer to this challenging question: are the laws of physics unique and was our big bang the only one? … According to some speculations the number of distinct varieties of space—each the arena for a universe with its own laws—could exceed the total number of atoms in all the galaxies we see. … So do we live in the aftermath of one big bang among many, just as our solar system is merely one of many planetary systems in our galaxy? (2006)

In 'Martin Rees Forecasts the Future', New Scientist (18 Nov 2006), No. 2578.

I hope that in due time the chemists will justify their proceedings by some large generalisations deduced from the infinity of results which they have collected. For me I am left hopelessly behind and I will acknowledge to you that through my bad memory organic chemistry is to me a sealed book. Some of those here, [August] Hoffman for instance, consider all this however as scaffolding, which will disappear when the structure is built. I hope the structure will be worthy of the labour. I should expect a better and a quicker result from the study of the powers of matter, but then I have a predilection that way and am probably prejudiced in judgment.

Letter to Christian Schönbein (9 Dec 1852), The Letters of Faraday and Schoenbein, 1836-1862 (1899), 209-210.

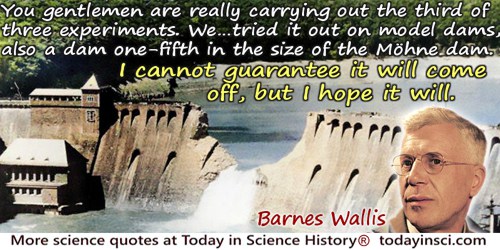

I hope they all come back.

About the crews dropping his “dambuster” bombs during World War II. As quoted in W. B. Bartlett, Dam Busters: In the Words of the Bomber Crews (2011, 2013), 103. Wallis said this to Wing Cdr G. P. Gibson, leader of the force of Lancasters of Bomber Command on the raid. As described by historian Richard Morris, “At the final briefing late on the Sunday afternoon, Wallis had addressed 19 crews. The next day, only 11 of them came back. Fifty-six of the faces into which he had looked just a few hours before were gone, and all but three of them were dead.”

I hope when I get to Heaven I shall not find the women playing second fiddle.

(Shortly before her death)

(Shortly before her death)

I hope you enjoy the absence of pupils … the total oblivion of them for definite intervals is a necessary condition for doing them justice at the proper time.

Letter to Lewis Campbell (21 Apr 1862). In P.M. Harman (ed.), The Scientific Letters and Papers of James Clerk Maxwell (1990), Vol. 1, 712.

I hope you have not murdered too completely your own and my child.

Referring to their independently conceived ideas on the origin of species.

Referring to their independently conceived ideas on the origin of species.

Letter to A. R. Wallace, March 1869. In J. Marchant, Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences (1916), Vol. 1, 240.

I love to read the dedications of old books written in monarchies—for they invariably honor some (usually insignificant) knight or duke with fulsome words of sycophantic insincerity, praising him as the light of the universe (in hopes, no doubt, for a few ducats to support future work); this old practice makes me feel like such an honest and upright man, by comparison, when I put a positive spin, perhaps ever so slightly exaggerated, on a grant proposal.

From essay 'The Razumovsky Duet', collected in The Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History (1995, 1997), 263.

I tell my students, with a feeling of pride that I hope they will share, that the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen that make up ninety-nine per cent of our living substance were cooked in the deep interiors of earlier generations of dying stars. Gathered up from the ends of the universe, over billions of years, eventually they came to form, in part, the substance of our sun, its planets, and ourselves. Three billion years ago, life arose upon the earth. It is the only life in the solar system.

From speech given at an anti-war teach-in at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, (4 Mar 1969) 'A Generation in Search of a Future', as edited by Ron Dorfman for Chicago Journalism Review, (May 1969).

I think it’s a mistake to ever look for hope outside of one’s self.

After the Fall. Quoted in Kim Lim (ed.), 1,001 Pearls of Spiritual Wisdom: Words to Enrich, Inspire, and Guide Your Life (2014), 250

I think that support of this [stem cell] research is a pro-life pro-family position. This research holds out hope for more than 100 million Americans.

In Eve Herold, George Daley, Stem Cell Wars (2007), 39.