Routine Quotes (27 quotes)

[My favourite fellow of the Royal Society is the Reverend Thomas Bayes, an obscure 18th-century Kent clergyman and a brilliant mathematician who] devised a complex equation known as the Bayes theorem, which can be used to work out probability distributions. It had no practical application in his lifetime, but today, thanks to computers, is routinely used in the modelling of climate change, astrophysics and stock-market analysis.

Quoted in Max Davidson, 'Bill Bryson: Have faith, science can solve our problems', Daily Telegraph (26 Sep 2010)

A life spent in the routine of science need not destroy the attractive human element of a woman's nature.

Said of Williamina Paton Fleming 1857- 1911, American Astronomer.

Said of Williamina Paton Fleming 1857- 1911, American Astronomer.

Obituary of Williamina Paton Fleming, Science, 1911, 33, 988.

A mathematician who can only generalise is like a monkey who can only climb UP a tree. ... And a mathematician who can only specialise is like a monkey who can only climb DOWN a tree. In fact neither the up monkey nor the down monkey is a viable creature. A real monkey must find food and escape his enemies and so must be able to incessantly climb up and down. A real mathematician must be able to generalise and specialise. ... There is, I think, a moral for the teacher. A teacher of traditional mathematics is in danger of becoming a down monkey, and a teacher of modern mathematics an up monkey. The down teacher dishing out one routine problem after another may never get off the ground, never attain any general idea. and the up teacher dishing out one definition after the other may never climb down from his verbiage, may never get down to solid ground, to something of tangible interest for his pupils.

From 'A Story With A Moral', Mathematical Gazette (Jun 1973), 57, No. 400, 86-87

A teacher of mathematics has a great opportunity. If he fills his allotted time with drilling his students in routine operations he kills their interest, hampers their intellectual development, and misuses his opportunity. But if he challenges the curiosity of his students by setting them problems proportionate to their knowledge, and helps them to solve their problems with stimulating questions, he may give them a taste for, and some means of, independent thinking.

In How to Solve It (1948), Preface.

Apart from its healthful mental training as a branch of ordinary education, geology as an open-air pursuit affords an admirable training in habits of observation, furnishes a delightful relief from the cares and routine of everyday life, takes us into the open fields and the free fresh face of nature, leads us into all manner of sequestered nooks, whither hardly any other occupation or interest would be likely to send us, sets before us problems of the highest interest regarding the history of the ground beneath our feet, and thus gives a new charm to scenery which may be already replete with attractions.

Outlines of Field-Geology (1900), 251-2.

Bradley is one of the few basketball players who have ever been appreciatively cheered by a disinterested away-from-home crowd while warming up. This curious event occurred last March, just before Princeton eliminated the Virginia Military Institute, the year’s Southern Conference champion, from the NCAA championships. The game was played in Philadelphia and was the last of a tripleheader. The people there were worn out, because most of them were emotionally committed to either Villanova or Temple-two local teams that had just been involved in enervating battles with Providence and Connecticut, respectively, scrambling for a chance at the rest of the country. A group of Princeton players shooting basketballs miscellaneously in preparation for still another game hardly promised to be a high point of the evening, but Bradley, whose routine in the warmup time is a gradual crescendo of activity, is more interesting to watch before a game than most players are in play. In Philadelphia that night, what he did was, for him, anything but unusual. As he does before all games, he began by shooting set shots close to the basket, gradually moving back until he was shooting long sets from 20 feet out, and nearly all of them dropped into the net with an almost mechanical rhythm of accuracy. Then he began a series of expandingly difficult jump shots, and one jumper after another went cleanly through the basket with so few exceptions that the crowd began to murmur. Then he started to perform whirling reverse moves before another cadence of almost steadily accurate jump shots, and the murmur increased. Then he began to sweep hook shots into the air. He moved in a semicircle around the court. First with his right hand, then with his left, he tried seven of these long, graceful shots-the most difficult ones in the orthodoxy of basketball-and ambidextrously made them all. The game had not even begun, but the presumably unimpressible Philadelphians were applauding like an audience at an opera.

A Sense of Where You Are: Bill Bradley at Princeton

Commitment to the Space Shuttle program is the right step for America to take, in moving out from our present beach-head in the sky to achieve a real working presence in space—because the Space Shuttle will give us routine access to space by sharply reducing costs in dollars and preparation time.

Statement by President Nixon (5 Jan 1972).

Current manned space flights are complex missions that involve thousands of people. Someday, however, space vehicles will fly in and out of earth orbit in a more routine manner, and the usefulness of space to science and, in fact, to all persons will have reached a highly desirable plateau.

In 'After Apollo, What?', Science Teacher (Sep 1969), 36, No. 6. 22.

I have decided today that the United States should proceed at once with the development of an entirely new type of space transportation system designed to help transform the space frontier of the 1970s into familiar territory, easily accessible for human endeavor in the 1980s and ’90s.

This system will center on a space vehicle that can shuttle repeatedly from Earth to orbit and back. It will revolutionize transportation into near space, by routinizing it. It will take the astronomical costs out of astronautics. In short, it will go a long way toward delivering the rich benefits of practical space utilization and the valuable spin-offs from space efforts into the daily lives of Americans and all people.

Statement by President Nixon (5 Jan 1972).

I think it perfectly just, that he who, from the love of experiment, quits an approved for an uncertain practice, should suffer the full penalty of Egyptian law against medical innovation; as I would consign to the pillory, the wretch, who out of regard to his character, that is, to his fees, should follow the routine, when, from constant experience he is sure that his patient will die under it, provided any, not inhuman, deviation would give his patient a chance.

From his researches in Fever, 196. In John Edmonds Stock, Memoirs of the life of Thomas Beddoes (1810), 400.

I travel a lot; I hate having my life disrupted by routine.

…...

In departing from any settled opinion or belief, the variation, the change, the break with custom may come gradually; and the way is usually prepared; but the final break is made, as a rule, by some one individual, … who sees with his own eyes, and with an instinct or genius for truth, escapes from the routine in which his fellows live. But he often pays dearly for his boldness.

In The Harveian Oration, delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London (18 Oct 1906). Printed in 'The Growth of Truth, as Illustrated in the Discovery of the Circulation of Blood', The Lancet (27 Oct 1906), Vol. 2, Pt. 2, 1114.

It is exceptional that one should be able to acquire the understanding of a process without having previously acquired a deep familiarity with running it, with using it, before one has assimilated it in an instinctive and empirical way. Thus any discussion of the nature of intellectual effort in any field is difficult, unless it presupposes an easy, routine familiarity with that field. In mathematics this limitation becomes very severe.

In 'The Mathematician', Works of the Mind (1947), 1, No. 1. Collected in James Roy Newman (ed.), The World of Mathematics (1956), Vol. 4, 2053.

It is not error which opposes the progress of truth; it is indolence, obstinacy, the spirit of routine, every thing which favors inaction.

In Fielding Hudson Garrison, An Introduction to the History of Medicine (1929), 33.

Kidney transplants seem so routine now. But the first one was like Lindbergh’s flight across the ocean.

In interview with reporter Gina Kolata, '2 American Transplant Pioneers Win Nobel Prize in Medicine', New York Times (9 Oct 1990).

Nothing will sustain you more potently than the power to recognize in your humdrum routine, as perhaps it may be thought, the true poetry of life—the poetry of the commonplace, of the ordinary man, of the plain, toil-worn woman, with their loves and their joys, their sorrows and their griefs.

From address 'The Student Life', No. 20 in Aequanimitas and other Addresses (1904, 1906), 423. This was a farewell address to American and Canadian medical students.

One of the gladdest moments of human life, methinks, is the departure upon a distant journey into unknown lands. Shaking off with one mighty effort the fetters of habit, the leaden weight of routine, the cloak of many cares and the slavery of home, man feel once more happy.

In Zanzibar: City, Island, and Coast (1872), Vol. 1, 16.

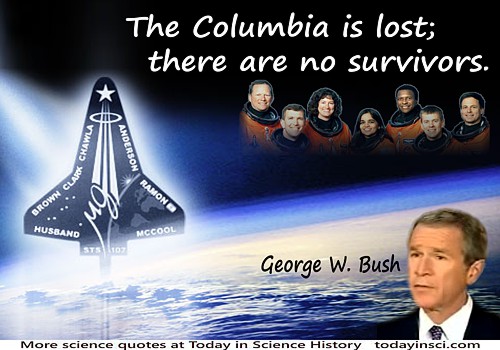

The Columbia is lost; there are no survivors. … In an age when space flight has come to seem almost routine, it is easy to overlook the dangers of travel by rocket, and the difficulties of navigating the fierce outer atmosphere of the Earth. These astronauts knew the dangers, and they faced them willingly, knowing they had a high and noble purpose in life. Because of their courage and daring idealism, we will miss them all the more. … The cause in which they died will continue. Mankind is led into the darkness beyond our world by the inspiration of discovery and the longing to understand. Our journey into space will go on.

Address to the Nation on the Space Shuttle Columbia tragedy, from the Cabinet Room (1 Feb 2003). In William J. Federer, A Treasury of Presidential Quotations (2004), 437.

The discovery in 1846 of the planet Neptune was a dramatic and spectacular achievement of mathematical astronomy. The very existence of this new member of the solar system, and its exact location, were demonstrated with pencil and paper; there was left to observers only the routine task of pointing their telescopes at the spot the mathematicians had marked.

In J.R. Newman (ed.), 'Commentary on John Couch Adams', The World of Mathematics (1956), 820.

The end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century were remarkable for the small amount of scientific movement going on in this country, especially in its more exact departments. ... Mathematics were at the last gasp, and Astronomy nearly so—I mean in those members of its frame which depend upon precise measurement and systematic calculation. The chilling torpor of routine had begun to spread itself over all those branches of Science which wanted the excitement of experimental research.

Quoted in Sophia Elizabeth De Morgan, Memoir of Augustus De Morgan (1882), 41

The highest reach of science is, one may say, an inventive power, a faculty of divination, akin to the highest power exercised in poetry; therefore, a nation whose spirit is characterised by energy may well be eminent in science; and we have Newton. Shakspeare [sic] and Newton: in the intellectual sphere there can be no higher names. And what that energy, which is the life of genius, above everything demands and insists upon, is freedom; entire independence of all authority, prescription and routine, the fullest room to expand as it will.

'The Literary Influence of Acadennes' Essays in Criticism (1865), in R.H. Super (ed.) The Complete Prose Works of Matthew Arnold: Lectures and Essays in Criticism (1962), Vol. 3, 238.

The laboratory routine, which involves a great deal of measurement, filing, and tabulation, is either my lifeline or my chief handicap, I hardly know which.

(1949). Epigraph in Susan Elizabeth Hough, Richter's Scale: Measure of an Earthquake, Measure of a Man (2007), 62.

The routine produces. But each day, nevertheless, when you try to get started you have to transmogrify, transpose yourself; you have to go through some kind of change from being a normal human being, into becoming some kind of slave.

I simply don’t want to break through that membrane. I’d do anything to avoid it. You have to get there and you don’t want to go there because there’s so much pressure and so much strain and you just want to stay on the outside and be yourself. And so the day is a constant struggle to get going.

And if somebody says to me, You’re a prolific writer—it seems so odd. It’s like the difference between geological time and human time. On a certain scale, it does look like I do a lot. But that’s my day, all day long, sitting there wondering when I’m going to be able to get started. And the routine of doing this six days a week puts a little drop in a bucket each day, and that’s the key. Because if you put a drop in a bucket every day, after three hundred and sixty-five days, the bucket’s going to have some water in it.

I simply don’t want to break through that membrane. I’d do anything to avoid it. You have to get there and you don’t want to go there because there’s so much pressure and so much strain and you just want to stay on the outside and be yourself. And so the day is a constant struggle to get going.

And if somebody says to me, You’re a prolific writer—it seems so odd. It’s like the difference between geological time and human time. On a certain scale, it does look like I do a lot. But that’s my day, all day long, sitting there wondering when I’m going to be able to get started. And the routine of doing this six days a week puts a little drop in a bucket each day, and that’s the key. Because if you put a drop in a bucket every day, after three hundred and sixty-five days, the bucket’s going to have some water in it.

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/5997/john-mcphee-the-art-of-nonfiction-no-3-john-mcphee

To ask what qualities distinguish good from routine scientific research is to address a question that should be of central concern to every scientist. We can make the question more tractable by rephrasing it, “What attributes are shared by the scientific works which have contributed importantly to our understanding of the physical world—in this case the world of living things?” Two of the most widely accepted characteristics of good scientific work are generality of application and originality of conception. . These qualities are easy to point out in the works of others and, of course extremely difficult to achieve in one’s own research. At first hearing novelty and generality appear to be mutually exclusive, but they really are not. They just have different frames of reference. Novelty has a human frame of reference; generality has a biological frame of reference. Consider, for example, Darwinian Natural Selection. It offers a mechanism so widely applicable as to be almost coexistent with reproduction, so universal as to be almost axiomatic, and so innovative that it shook, and continues to shake, man’s perception of causality.

In 'Scientific innovation and creativity: a zoologist’s point of view', American Zoologist (1982), 22, 230.

Try to find pleasure in the speed that you’re not used to. Changing the way you do routine things allows a new person to grow inside of you.

Quoted in Kim Lim (ed.), 1,001 Pearls of Spiritual Wisdom: Words to Enrich, Inspire, and Guide Your Life (2014), 236

We are the children of a technological age. We have found streamlined ways of doing much of our routine work. Printing is no longer the only way of reproducing books. Reading them, however, has not changed...

…...

Without theory, practice is but routine born of habit. Theory alone can bring forth and develop the spirit of invention. ... [Do not] share the opinion of those narrow minds who disdain everything in science which has not an immediate application. ... A theoretical discovery has but the merit of its existence: it awakens hope, and that is all. But let it be cultivated, let it grow, and you will see what it will become.

Inaugural Address as newly appointed Professor and Dean (Sep 1854) at the opening of the new Faculté des Sciences at Lille (7 Dec 1854). In René Vallery-Radot, The Life of Pasteur, translated by Mrs. R. L. Devonshire (1919), 76.

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --