Stand Quotes (286 quotes)

...I may perhaps venture a short word on the question much discussed in certain quarters, whether in the work of excavation it is a good thing to have cooperation between men and women ... Of a mixed dig ... I have seen something, and it is an experiment that I would be reluctant to try again. I would grant if need be that women are admirable fitted for the work, yet I would uphold that they should undertake it by themselves ... the work of an excavator on the dig and off it lays on those who share it a bond of closer daily intercourse than is conceivable ... between men and women, except in chance cases, I do not believe that such close and unavoidable companionship can ever be other than a source of irritation; at any rate, I believe that however it may affect women, the ordinary male at least cannot stand it ... A minor ... objection lies in one particular form of contraint ... moments will occur on the best regulated dig when you want to say just what you think without translation, which before the ladies, whatever their feelings about it, cannot be done.

Archaeological Excavation (1915), 63-64. In Getzel M. Cohen and Martha Sharp Joukowsky Breaking Ground (2006), 557-558.

By (), 163-164.

…indeed what reason may not go to Schoole to the wisdome of Bees, Aunts, and Spiders? what wise hand teacheth them to doe what reason cannot teach us? Ruder heads stand amazed at those prodigious pieces of nature, Whales, Elephants, Dromidaries and Camels; these I confesse, are the Colossus and Majestick pieces of her hand; but in these narrow Engines there is more curious Mathematicks, and the civilitie of these little Citizens more neatly sets forth the wisedome of their Maker.

In Religio Medici and Other Writings (1909), 17.

...neither is it possible to discover the more remote and deeper parts of any science, if you stand but upon the level of the same science, and ascend not to a higher science.

Francis Bacon, Basil Montagu (Ed.), The Works of Francis Bacon (1852), Vol. 1, 173.

[1.] And first I suppose that there is diffused through all places an aethereal substance capable of contraction & dilatation, strongly elastick, & in a word, much like air in all respects, but far more subtile.

2. I suppose this aether pervades all gross bodies, but yet so as to stand rarer in their pores then in free spaces, & so much ye rarer as their pores are less ...

3. I suppose ye rarer aether within bodies & ye denser without them, not to be terminated in a mathematical superficies, but to grow gradually into one another.

2. I suppose this aether pervades all gross bodies, but yet so as to stand rarer in their pores then in free spaces, & so much ye rarer as their pores are less ...

3. I suppose ye rarer aether within bodies & ye denser without them, not to be terminated in a mathematical superficies, but to grow gradually into one another.

Letter to Robert Boyle (28 Feb 1678/9). In H. W. Turnbull (ed.), The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, 1676-1687 (1960), Vol. 2, 289.

[1665-06-17] It stroke me very deep this afternoon, going with a hackney-coach from my Lord Treasurer's down Holborne - the coachman I found to drive easily and easily; at last stood still, and came down hardly able to stand; and told me that he was suddenly stroke very sick and almost blind. So I light and went into another coach, with a sad heart for the poor man and trouble for myself, lest he should have been stroke with the plague - being at that end of the town that I took him up. But God have mercy upon us all.

Diary of Samuel Pepys (17 Jun 1665)

[I have seen] workers in whom certain morbid affections gradually arise from some particular posture of the limbs or unnatural movements of the body called for while they work. Such are the workers who all day stand or sit, stoop or are bent double, who run or ride or exercise their bodies in all sorts of [excess] ways. ... the harvest of diseases reaped by certain workers ... [from] irregular motions in unnatural postures of the body.

translation published by the University of Chicago Press, 1940

[Regarding mathematics,] there are now few studies more generally recognized, for good reasons or bad, as profitable and praiseworthy. This may be true; indeed it is probable, since the sensational triumphs of Einstein, that stellar astronomy and atomic physics are the only sciences which stand higher in popular estimation.

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 63-64.

[Society's rights to employ the scopolamine (“truth serum”) drug supersede those of a criminal.] It therefore stands to reason, that where there is a safe and humane method existing to evoke the truth from the consciousness of a suspect society is entitled to have that truth.

Quoted from presentation at the first annual meeting of the Eastern Society of Anesthetists at the Hotel McAlpin, as reported in '“Truth Serum” Test Proves Its Power', New York Times (22 Oct 1924), 14.

[The more science discovers and] the more comprehension it gives us of the mechanisms of existence, the more clearly does the mystery of existence itself stand out.

Julian Huxley and Aldous Huxley, Aldous Huxley, 1894-1963: A Memorial Volume (1965), 21.

[Wolfgang Bolyai] was extremely modest. No monument, said he, should stand over his grave, only an apple-tree, in memory of the three apples: the two of Eve and Paris, which made hell out of earth, and that of Newton, which elevated the earth again into the circle of the heavenly bodies.

In History of Elementary Mathematics (1910), 273.

δος μοι που στω και κινω την γην — Dos moi pou sto kai kino taen gaen (in epigram form, as given by Pappus, classical Greek).

δος μοι πα στω και τα γαν κινάσω — Dos moi pa sto kai tan gan kinaso (Doric Greek).

Give me a place to stand on and I can move the Earth.

About four centuries before Pappas, but about three centuries after Archimedes lived, Plutarch had written of Archimedes' understanding of the lever:

Archimedes, a kinsman and friend of King Hiero, wrote to him that with a given force, it was possible to move any given weight; and emboldened, as it is said, by the strength of the proof, he asserted that, if there were another world and he could go to it, he would move this one.

A commonly-seen expanded variation of the aphorism is:

Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand, and I can move the earth.

δος μοι πα στω και τα γαν κινάσω — Dos moi pa sto kai tan gan kinaso (Doric Greek).

Give me a place to stand on and I can move the Earth.

About four centuries before Pappas, but about three centuries after Archimedes lived, Plutarch had written of Archimedes' understanding of the lever:

Archimedes, a kinsman and friend of King Hiero, wrote to him that with a given force, it was possible to move any given weight; and emboldened, as it is said, by the strength of the proof, he asserted that, if there were another world and he could go to it, he would move this one.

A commonly-seen expanded variation of the aphorism is:

Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand, and I can move the earth.

As attributed to Pappus (4th century A.D.) and Plutarch (c. 46-120 A.D.), in Sherman K. Stein, Archimedes: What Did He Do Besides Cry Eureka? (1999), 5, where it is also stated that Archimedes knew that ropes and pulley exploit “the principle of the lever, where distance is traded for force.” Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis, in his book, Archimedes (1956), Vol. 12., 15. writes that Hiero invited Archimedes to demonstrate his claim on a ship from the royal fleet, drawn up onto land and there loaded with a large crew and freight, and Archimedes easily succeeded. Thomas Little Heath in The Works of Archimedes (1897), xix-xx, states according to Athenaeus, the mechanical contrivance used was not pulleys as given by Plutarch, but a helix., Heath provides cites for Pappus Synagoge, Book VIII, 1060; Plutarch, Marcellus, 14; and Athenaeus v. 207 a-b. What all this boils down to, in the opinion of the Webmaster, is the last-stated aphorism would seem to be not the actual words of Archimedes (c. 287 – 212 B.C.), but restatements of the principle attributed to him, formed by other writers centuries after his lifetime.

The Redwoods

Here, sown by the Creator's hand,

In serried ranks, the Redwoods stand;

No other clime is honored so,

No other lands their glory know.

The greatest of Earth's living forms,

Tall conquerors that laugh at storms;

Their challenge still unanswered rings,

Through fifty centuries of kings.

The nations that with them were young,

Rich empires, with their forts far-flung,

Lie buried now—their splendor gone;

But these proud monarchs still live on.

So shall they live, when ends our day,

When our crude citadels decay;

For brief the years allotted man,

But infinite perennials' span.

This is their temple, vaulted high,

And here we pause with reverent eye,

With silent tongue and awe-struck soul;

For here we sense life's proper goal;

To be like these, straight, true and fine,

To make our world, like theirs, a shrine;

Sink down, oh traveler, on your knees,

God stands before you in these trees.

Here, sown by the Creator's hand,

In serried ranks, the Redwoods stand;

No other clime is honored so,

No other lands their glory know.

The greatest of Earth's living forms,

Tall conquerors that laugh at storms;

Their challenge still unanswered rings,

Through fifty centuries of kings.

The nations that with them were young,

Rich empires, with their forts far-flung,

Lie buried now—their splendor gone;

But these proud monarchs still live on.

So shall they live, when ends our day,

When our crude citadels decay;

For brief the years allotted man,

But infinite perennials' span.

This is their temple, vaulted high,

And here we pause with reverent eye,

With silent tongue and awe-struck soul;

For here we sense life's proper goal;

To be like these, straight, true and fine,

To make our world, like theirs, a shrine;

Sink down, oh traveler, on your knees,

God stands before you in these trees.

In The Record: Volumes 60-61 (1938), 39.

[Students or readers about teachers or authors.] They will listen with both ears to what is said by the men just a step or two ahead of them, who stand nearest to them, and within arm’s reach. A guide ceases to be of any use when he strides so far ahead as to be hidden by the curvature of the earth.

From Lecture (5 Apr 1917) at Hackley School, Tarrytown, N.Y., 'Choosing Books', collected in Canadian Stories (1918), 150.

A stands for atom; it is so small No one has ever seen it at all.

B stands for bomb; the bombs are much bigger,

So, brother, do not be too fast on the trigger.

H has become a most ominous letter.

It means something bigger if not something better.

B stands for bomb; the bombs are much bigger,

So, brother, do not be too fast on the trigger.

H has become a most ominous letter.

It means something bigger if not something better.

As quoted in Robert Coughlan, 'Dr. Edward Teller’s Magnificent Obsession', Life (6 Sep 1954), 74.

I cannot give any scientist of any age better advice than this: the intensity of the conviction that a hypothesis is true has no bearing on whether it is true or not. The importance of the strength of our conviction is only to provide a proportionally strong incentive to find out if the hypothesis will stand up to critical examination.

In Advice to a Young Scientist (1979), 39.

Question: Explain how to determine the time of vibration of a given tuning-fork, and state what apparatus you would require for the purpose.

Answer: For this determination I should require an accurate watch beating seconds, and a sensitive ear. I mount the fork on a suitable stand, and then, as the second hand of my watch passes the figure 60 on the dial, I draw the bow neatly across one of its prongs. I wait. I listen intently. The throbbing air particles are receiving the pulsations; the beating prongs are giving up their original force; and slowly yet surely the sound dies away. Still I can hear it, but faintly and with close attention; and now only by pressing the bones of my head against its prongs. Finally the last trace disappears. I look at the time and leave the room, having determined the time of vibration of the common “pitch” fork. This process deteriorates the fork considerably, hence a different operation must be performed on a fork which is only lent.

Answer: For this determination I should require an accurate watch beating seconds, and a sensitive ear. I mount the fork on a suitable stand, and then, as the second hand of my watch passes the figure 60 on the dial, I draw the bow neatly across one of its prongs. I wait. I listen intently. The throbbing air particles are receiving the pulsations; the beating prongs are giving up their original force; and slowly yet surely the sound dies away. Still I can hear it, but faintly and with close attention; and now only by pressing the bones of my head against its prongs. Finally the last trace disappears. I look at the time and leave the room, having determined the time of vibration of the common “pitch” fork. This process deteriorates the fork considerably, hence a different operation must be performed on a fork which is only lent.

Genuine student answer* to an Acoustics, Light and Heat paper (1880), Science and Art Department, South Kensington, London, collected by Prof. Oliver Lodge. Quoted in Henry B. Wheatley, Literary Blunders (1893), 176-7, Question 4. (*From a collection in which Answers are not given verbatim et literatim, and some instances may combine several students' blunders.)

The Word Reason in the English Language has different Significances: sometimes it is taken for true, and clear Principles: Sometimes for clear, and fair deductions from those Principles: and sometimes for Cause, and particularly the final Cause: but the Consideration I shall have of it here, is in a Signification different from all these; and that is, as it stands for a Faculty of Man, That Faculty, whereby Man is supposed to be distinguished from Beasts; and wherein it is evident he much surpasses them.

In 'Of Reason', Essay Concerning Humane Understanding (1690), Book 4, Ch. 17, Sec. 1, 341.

A fact is like a sack which won’t stand up if it’s empty. In order that it may stand up, one has to put into it the reason and sentiment which caused it to exist.

Character, The Father, in play Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921), Act 1. Collected in John Gassner and Burns Mantle, A Treasury of the Theatre (1935), Vol. 2, 507.

A few of the results of my activities as a scientist have become embedded in the very texture of the science I tried to serve—this is the immortality that every scientist hopes for. I have enjoyed the privilege, as a university teacher, of being in a position to influence the thought of many hundreds of young people and in them and in their lives I shall continue to live vicariously for a while. All the things I care for will continue for they will be served by those who come after me. I find great pleasure in the thought that those who stand on my shoulders will see much farther than I did in my time. What more could any man want?

In 'The Meaning of Death,' in The Humanist Outlook edited by A. J. Ayer (1968) [See Gerald Holton and Sir Isaac Newton].

A frequent misunderstanding of my vision of Gaia is that I champion complacence, that I claim feedback will always protect the environment from any serious harm that humans might do. It is sometimes more crudely put as “Lovelock’s Gaia gives industry the green light to pollute at will.” The truth is almost diametrically opposite. Gaia, as I see her, is no doting mother tolerant of misdemeanors, nor is she some fragile and delicate damsel in danger from brutal mankind. She is stern and tough, always keeping the world warm and comfortable for those who obey the rules, but ruthless in her destruction of those who transgress. Her unconscious goal is a planet fit for life. If humans stand in the way of this, we shall be eliminated with as little pity as would be shown by the micro-brain of an intercontinental ballistic nuclear missile in full flight to its target.

In The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth (1999), 199.

A Lady with a Lamp shall stand

In the great history of the land,

A noble type of good,

Heroic womanhood.

In the great history of the land,

A noble type of good,

Heroic womanhood.

'Santa Filomena' (1857), The Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1867), 333.

A large part of the training of the engineer, civil and military, as far as preparatory studies are concerned; of the builder of every fabric of wood or stone or metal designed to stand upon the earth, or bridge the stream, or resist or float upon the wave; of the surveyor who lays out a building lot in a city, or runs a boundary line between powerful governments across a continent; of the geographer, navigator, hydrographer, and astronomer,—must be derived from the mathematics.

In 'Academical Education', Orations and Speeches on Various Occasions (1870), Vol. 3, 513.

A man cannot well stand by himself, and so he is glad to join a party; because if he does not find rest there, he at any rate finds quiet and safety.

In The Maxims and Reflections of Goethe (1906), 183.

A man’s value to the community depends primarily on how far his feelings, thoughts, and actions are directed towards promoting the good of his fellows. We call him good or bad according to how he stands in this matter. It looks at first sight as if our estimate of a man depended entirely on his social qualities.

…...

A most vile face! and yet she spends me forty pound a year in Mercury and Hogs Bones. All her teeth were made in the Black-Fryars, both her Eyebrows i’ the Strand, and her Hair in Silver-street. Every part of Town owns a Piece of her.

A reference to artificial teeth by character Otter, speaking of his wife, in Epicoene: or, The Silent Woman (1609), Act IV, Sc. 2, 64. Also, True-wit makes a specific reference to “false Teeth” in Act I, Sc. 1, 10.

A noiseless, patient spider,

I mark’d, where on a little promontory, it stood, isolated;

Mark’d how, to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself

Ever unreeling them—ever tirelessly speeding them.

I mark’d, where on a little promontory, it stood, isolated;

Mark’d how, to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself

Ever unreeling them—ever tirelessly speeding them.

In 'A Noiseless Patient Spider', Broadway: A London Magazine (1868), reprinted in Leaves of Grass (5th ed., 1871, 1888), 343.

A schism has taken place among the chemists. A particular set of them in France have undertaken to remodel all the terms of the science, and to give every substance a new name, the composition, and especially the termination of which, shall define the relation in which it stands to other substances of the same family, But the science seems too much in its infancy as yet, for this reformation; because in fact, the reformation of this year must be reformed again the next year, and so on, changing the names of substances as often as new experiments develop properties in them undiscovered before. The new nomenclature has, accordingly, been already proved to need numerous and important reformations. ... It is espoused by the minority here, and by the very few, indeed, of the foreign chemists. It is particularly rejected in England.

Letter to Dr. Willard (Paris, 1788). In Thomas Jefferson and John P. Foley (ed.), The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia (1900), 135. From H.A. Washington, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (1853-54). Vol 3, 15.

A small cabin stands in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, about a hundred yards off a trail that crosses the Cascade Range. In midsummer, the cabin looked strange in the forest. It was only twelve feet square, but it rose fully two stories and then had a high and steeply peaked roof. From the ridge of the roof, moreover, a ten-foot pole stuck straight up. Tied to the top of the pole was a shovel. To hikers shedding their backpacks at the door of the cabin on a cold summer evening—as the five of us did—it was somewhat unnerving to look up and think of people walking around in snow perhaps thirty-five feet above, hunting for that shovel, then digging their way down to the threshold.

In Encounters with the Archdruid (1971), 3.

A vision of the whole of life!. Could any human undertaking be ... more grandiose? This attempt stands without rival as the most audacious enterprise in which the mind of man has ever engaged ... Here is man, surrounded by the vastness of a universe in which he is only a tiny and perhaps insignificant part—and he wants to understand it.

…...

A Vulgar Mechanick can practice what he has been taught or seen done, but if he is in an error he knows not how to find it out and correct it, and if you put him out of his road, he is at a stand; Whereas he that is able to reason nimbly and judiciously about figure, force and motion, is never at rest till he gets over every rub.

Letter (25 May 1694) to Nathaniel Hawes. In J. Edleston (ed.), Correspondence of Sir Isaac Newton and Professor Cotes (1850), 284.

A work of genius is something like the pie in the nursery song, in which the four and twenty blackbirds are baked. When the pie is opened, the birds begin to sing. Hereupon three fourths of the company run away in a fright; and then after a time, feeling ashamed, they would fain excuse themselves by declaring, the pie stank so, they could not sit near it. Those who stay behind, the men of taste and epicures, say one to another, We came here to eat. What business have birds, after they have been baked, to be alive and singing? This will never do. We must put a stop to so dangerous an innovation: for who will send a pie to an oven, if the birds come to life there? We must stand up to defend the rights of all the ovens in England. Let us have dead birds..dead birds for our money. So each sticks his fork into a bird, and hacks and mangles it a while, and then holds it up and cries, Who will dare assert that there is any music in this bird’s song?

Co-author with his brother Augustus William Hare Guesses At Truth, By Two Brothers: Second Edition: With Large Additions (1848), Second Series, 86. (The volume is introduced as “more than three fourths new.” This quote is identified as by Julius; Augustus had died in 1833.)

Aeroplanes are not designed by science, but by art in spite of some pretence and humbug to the contrary. I do not mean to suggest that engineering can do without science, on the contrary, it stands on scientific foundations, but there is a big gap between scientific research and the engineering product which has to be bridged by the art of the engineer.

In John D. North, 'The Case for Metal Construction', The Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society, (Jan 1923), 27, 11.

Among the scenes which are deeply impressed on my mind, none exceed in sublimity the primeval [tropical] forests, ... temples filled with the varied productions of the God of Nature. No one can stand in these solitudes unmoved, and not feel that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.

In What Mr. Darwin Saw in His Voyage Round the World in the Ship “Beagle” 1879, 170.

Among the scenes which are deeply impressed on my mind, none exceed in sublimity the primeval forests undefaced by the hand of man; whether those of Brazil, where the powers of Life are predominant, or those of Tierra del Fuego, where Death and Decay prevail. Both are temples filled with the varied productions of the God of Nature: no one can stand in these solitudes unmoved, and not feel that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.

Journal of Researches: into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World (1839), ch. XXIII, 604-5.

An astronomer is a guy who stands around looking at heavenly bodies.

Quoted in M. Goran, A Treasury of Science Jokes (1986), 29.

An experiment is an observation that can be repeated, isolated and varied. The more frequently you can repeat an observation, the more likely are you to see clearly what is there and to describe accurately what you have seen. The more strictly you can isolate an observation, the easier does your task of observation become, and the less danger is there of your being led astray by irrelevant circumstances, or of placing emphasis on the wrong point. The more widely you can vary an observation, the more clearly will the uniformity of experience stand out, and the better is your chance of discovering laws.

In A Text-Book of Psychology (1909), 20.

Artificial intelligence is based on the assumption that the mind can be described as some kind of formal system manipulating symbols that stand for things in the world. Thus it doesn't matter what the brain is made of, or what it uses for tokens in the great game of thinking. Using an equivalent set of tokens and rules, we can do thinking with a digital computer, just as we can play chess using cups, salt and pepper shakers, knives, forks, and spoons. Using the right software, one system (the mind) can be mapped onto the other (the computer).

Machinery of the Mind: Inside the New Science of Artificial Intelligence (1986), 250.

As a result of the phenomenally rapid change and growth of physics, the men and women who did their great work one or two generations ago may be our distant predecessors in terms of the state of the field, but they are our close neighbors in terms of time and tastes. This may be an unprecedented state of affairs among professionals; one can perhaps be forgiven if one characterizes it epigrammatically with a disastrously mixed metaphor; in the sciences, we are now uniquely privileged to sit side-by-side with the giants on whose shoulders we stand.

In 'On the Recent Past of Physics', American Journal of Physics (1961), 29, 807.

As every circumstance relating to so capital a discovery as this (the greatest, perhaps, that has been made in the whole compass of philosophy, since the time of Sir Isaac Newton) cannot but give pleasure to all my readers, I shall endeavour to gratify them with the communication of a few particulars which I have from the best authority. The Doctor [Benjamin Franklin], after having published his method of verifying his hypothesis concerning the sameness of electricity with the matter lightning, was waiting for the erection of a spire in Philadelphia to carry his views into execution; not imagining that a pointed rod, of a moderate height, could answer the purpose; when it occurred to him, that, by means of a common kite, he could have a readier and better access to the regions of thunder than by any spire whatever. Preparing, therefore, a large silk handkerchief, and two cross sticks, of a proper length, on which to extend it, he took the opportunity of the first approaching thunder storm to take a walk into a field, in which there was a shed convenient for his purpose. But dreading the ridicule which too commonly attends unsuccessful attempts in science, he communicated his intended experiment to no body but his son, who assisted him in raising the kite.

The kite being raised, a considerable time elapsed before there was any appearance of its being electrified. One very promising cloud passed over it without any effect; when, at length, just as he was beginning to despair of his contrivance, he observed some loose threads of the hempen string to stand erect, and to avoid one another, just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor. Struck with this promising appearance, he inmmediately presented his knuckle to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark. Others succeeded, even before the string was wet, so as to put the matter past all dispute, and when the rain had wetted the string, he collected electric fire very copiously. This happened in June 1752, a month after the electricians in France had verified the same theory, but before he had heard of any thing that they had done.

The kite being raised, a considerable time elapsed before there was any appearance of its being electrified. One very promising cloud passed over it without any effect; when, at length, just as he was beginning to despair of his contrivance, he observed some loose threads of the hempen string to stand erect, and to avoid one another, just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor. Struck with this promising appearance, he inmmediately presented his knuckle to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark. Others succeeded, even before the string was wet, so as to put the matter past all dispute, and when the rain had wetted the string, he collected electric fire very copiously. This happened in June 1752, a month after the electricians in France had verified the same theory, but before he had heard of any thing that they had done.

The History and Present State of Electricity, with Original Experiments (1767, 3rd ed. 1775), Vol. 1, 216-7.

As for your doctrines I am prepared to go to the Stake if requisite ... I trust you will not allow yourself to be in any way disgusted or annoyed by the considerable abuse & misrepresentation which unless I greatly mistake is in store for you... And as to the curs which will bark and yelp - you must recollect that some of your friends at any rate are endowed with an amount of combativeness which (though you have often & justly rebuked it) may stand you in good stead - I am sharpening up my claws and beak in readiness.

Letter (23 Nov 1859) to Charles Darwin a few days after the publication of Origin of Species. In Charles Darwin, Frederick Burkhardt, Sydney Smith, The Correspondence of Charles Darwin: 1858-1859 (1992), Vol. 19, 390-391.

As he [Clifford] spoke he appeared not to be working out a question, but simply telling what he saw. Without any diagram or symbolic aid he described the geometrical conditions on which the solution depended, and they seemed to stand out visibly in space. There were no longer consequences to be deduced, but real and evident facts which only required to be seen. … So whole and complete was his vision that for the time the only strange thing was that anybody should fail to see it in the same way. When one endeavored to call it up again, and not till then, it became clear that the magic of genius had been at work, and that the common sight had been raised to that higher perception by the power that makes and transforms ideas, the conquering and masterful quality of the human mind which Goethe called in one word das Dämonische.

In Leslie Stephen and Frederick Pollock (eds.), Lectures and Essays by William Kingdon Clifford(1879), Vol. 1, Introduction, 4-5.

As I am writing, another illustration of ye generation of hills proposed above comes into my mind. Milk is as uniform a liquor as ye chaos was. If beer be poured into it & ye mixture let stand till it be dry, the surface of ye curdled substance will appear as rugged & mountanous as the Earth in any place.

Letter to Thomas Burnet (Jan 1680/1. In H. W. Turnbull (ed.), The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, 1676-1687 (1960), Vol. 2, 334.

Attempt the end and never stand to doubt;

Nothing's so hard, but search will find it out.

Nothing's so hard, but search will find it out.

'Seeke and Finde', Hesperides: Or, the Works Both Humane and Divine of Robert Herrick Esq. (1648). In J. Max Patrick (ed.), The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick (1963), 411.

Behind and permeating all our scientific activity, whether in critical analysis or in discovery, there is an elementary and overwhelming faith in the possibility of grasping the real world with out concepts, and, above all, faith in the truth over which we have no control but in the service of which our rationality stands or falls. Faith and intrinsic rationality are interlocked with one another

Christian Theology of Scientific Culture (1981), 63. In Vinoth Ramachandra, Subverting Global Myths: Theology and the Public Issues Shaping our World (2008), 187.

Between men of different studies and professions, may be observed a constant reciprocation of reproaches. The collector of shells and stones derides the folly of him who pastes leaves and flowers upon paper, pleases himself with colours that are perceptibly fading, and amasses with care what cannot be preserved. The hunter of insects stands amazed that any man can waste his short time upon lifeless matter, while many tribes of animals yet want their history. Every one is inclined not only to promote his own study, but to exclude all others from regard, and having heated his imagination with some favourite pursuit, wonders that the rest of mankind are not seized with the same passion.

From 'Numb. 83, Tuesday, January 1, 1750', The Rambler (1756), Vol. 2, 150.

But … the working scientist … is not consciously following any prescribed course of action, but feels complete freedom to utilize any method or device whatever which in the particular situation before him seems likely to yield the correct answer. … No one standing on the outside can predict what the individual scientist will do or what method he will follow.

In Reflections of a Physicist: A Collection of Essays (1955, 1980), 83.

But now that I was finally here, standing on the summit of Mount Everest, I just couldn’t summon the energy to care.

…...

But when we face the great questions about gravitation Does it require time? Is it polar to the 'outside of the universe' or to anything? Has it any reference to electricity? or does it stand on the very foundation of matter–mass or inertia? then we feel the need of tests, whether they be comets or nebulae or laboratory experiments or bold questions as to the truth of received opinions.

Letter to Michael Faraday, 9 Nov 1857. In P. M. Harman (ed.), The Scientific Letters and Papers of James Clerk Maxwell (1990), Vol. 1, 1846-1862, 551-2.

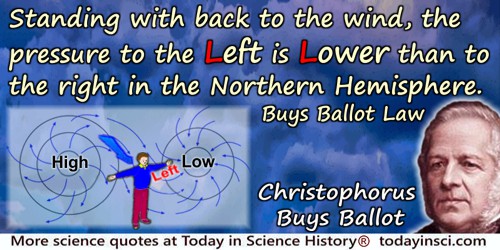

Buys Ballot Law: Standing with back to the wind, the pressure to the left is lower than to the right in the Northern Hemisphere.

Slightly reworded from the Glossary of Meteorology online at the site of the American Meteorological Society. Various statements of this law are found in different sources.

By destroying the biological character of phenomena, the use of averages in physiology and medicine usually gives only apparent accuracy to the results. From our point of view, we may distinguish between several kinds of averages: physical averages, chemical averages and physiological and pathological averages. If, for instance, we observe the number of pulsations and the degree of blood pressure by means of the oscillations of a manometer throughout one day, and if we take the average of all our figures to get the true or average blood pressure and to learn the true or average number of pulsations, we shall simply have wrong numbers. In fact, the pulse decreases in number and intensity when we are fasting and increases during digestion or under different influences of movement and rest; all the biological characteristics of the phenomenon disappear in the average. Chemical averages are also often used. If we collect a man's urine during twenty-four hours and mix all this urine to analyze the average, we get an analysis of a urine which simply does not exist; for urine, when fasting, is different from urine during digestion. A startling instance of this kind was invented by a physiologist who took urine from a railroad station urinal where people of all nations passed, and who believed he could thus present an analysis of average European urine! Aside from physical and chemical, there are physiological averages, or what we might call average descriptions of phenomena, which are even more false. Let me assume that a physician collects a great many individual observations of a disease and that he makes an average description of symptoms observed in the individual cases; he will thus have a description that will never be matched in nature. So in physiology, we must never make average descriptions of experiments, because the true relations of phenomena disappear in the average; when dealing with complex and variable experiments, we must study their various circumstances, and then present our most perfect experiment as a type, which, however, still stands for true facts. In the cases just considered, averages must therefore be rejected, because they confuse, while aiming to unify, and distort while aiming to simplify. Averages are applicable only to reducing very slightly varying numerical data about clearly defined and absolutely simple cases.

From An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine (1865), as translated by Henry Copley Greene (1957), 134-135.

Cayley was singularly learned in the work of other men, and catholic in his range of knowledge. Yet he did not read a memoir completely through: his custom was to read only so much as would enable him to grasp the meaning of the symbols and understand its scope. The main result would then become to him a subject of investigation: he would establish it (or test it) by algebraic analysis and, not infrequently, develop it so to obtain other results. This faculty of grasping and testing rapidly the work of others, together with his great knowledge, made him an invaluable referee; his services in this capacity were used through a long series of years by a number of societies to which he was almost in the position of standing mathematical advisor.

In Proceedings of London Royal Society (1895), 58, 11-12.

Common sense always speaks too late. Common sense is the guy who tells you you ought to have had your brakes relined last week before you smashed a front end this week. Common sense is the Monday morning quarterback who could have won the ball game if he had been on the team. But he never is. He’s high up in the stands with a flask on his hip. Common sense is the little man in a grey suit who never makes a mistake in addition. But it’s always somebody else’s money he’s adding up.

In novel, Playback (1958), Chap. 14, 95.

Do the day’s work. If it be to protect the rights of the weak, whoever objects, do it. If it be to help a powerful corporation better to serve the people, whatever the opposition, do that. Expect to be called a stand-patter, but don’t be a stand-patter. Expect to be called a demagogue, but don’t be a demagogue. Don’t hesitate to be as revolutionary as science. Don’t hesitate to be as reactionary as the multiplication table. Don’t expect to build up the weak by pulling down the strong. Don’t hurry to legislate. Give administration a chance to catch up with legislation.

Speech (7 Jan 1914), to the State Senate of Massachusetts upon election as its president. Collected in Coolidge, Have Faith in Massachusetts (1919, 2004), 7-8.

Doubtless many can recall certain books which have greatly influenced their lives, and in my own case one stands out especially—a translation of Hofmeister's epoch-making treatise on the comparative morphology of plants. This book, studied while an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, was undoubtedly the most important factor in determining the trend of my botanical investigation for many years.

D.H. Campbell, 'The Centenary of Wilhelm Hofmeister', Science (1925), 62, No. 1597, 127-128. Cited in William C. Steere, Obituary, 'Douglas Houghton Campbell', American Bryological and Lichenological Society, The Bryologist (1953), 127. The book to which Cambell refers is W. Hofmeister, On the Germination, Development, and Fructification of the Higher Cryptogamia, and on the Fructification of the Coniferae, trans. by Frederick Currey (1862).

Dream analysis stands or falls with [the hypothesis of the unconscious]. Without it the dream appears to be merely a freak of nature, a meaningless conglomerate of memory-fragments left over from the happenings of the day.

Dream Analysis in its Practical Application (1930), 1-2.

During the school period the student has been mentally bending over his desk; at the University he should stand up and look around. For this reason it is fatal if the first year at the University be frittered away in going over the old work in the old spirit. At school the boy painfully rises from the particular towards glimpses at general ideas; at the University he should start from general ideas and study their applications to concrete cases.

In 'The Rhythm of Education', The Aims of Education and Other Essays (1929), 26.

Educators may bring upon themselves unnecessary travail by taking a tactless and unjustifiable position about the relation between scientific and religious narratives. … The point is that profound but contradictory ideas may exist side by side, if they are constructed from different materials and methods and have different purposes. Each tells us something important about where we stand in the universe, and it is foolish to insist that they must despise each other.

In The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1995), 107.

England and all civilised nations stand in deadly peril of not having enough to eat. As mouths multiply, food resources dwindle. Land is a limited quantity, and the land that will grow wheat is absolutely dependent on difficult and capricious natural phenomena... I hope to point a way out of the colossal dilemma. It is the chemist who must come to the rescue of the threatened communities. It is through the laboratory that starvation may ultimately be turned into plenty... The fixation of atmospheric nitrogen is one of the great discoveries, awaiting the genius of chemists.

Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1898. Published in Chemical News, 1898, 78, 125.

Ethical axioms are found and tested not very differently from the axioms of science. Truth is what stands the test of experience.

…...

Every great scientist becomes a great scientist because of the inner self-abnegation with which he stands before truth, saying: “Not my will, but thine, be done.” What, then, does a man mean by saying, Science displaces religion, when in this deep sense science itself springs from religion?

In 'The Real Point of Conflict between Science and Religion', collected in Living Under Tension: Sermons On Christianity Today (1941), 148.

Every natural scientist who thinks with any degree of consistency at all will, I think, come to the view that all those capacities that we understand by the phrase psychic activities (Seelenthiitigkeiten) are but functions of the brain substance; or, to express myself a bit crudely here, that thoughts stand in the same relation to the brain as gall does to the liver or urine to the kidneys. To assume a soul that makes use of the brain as an instrument with which it can work as it pleases is pure nonsense; we would then be forced to assume a special soul for every function of the body as well.

In Physiologische Briefe für Gelbildete aIle Stünde (1845-1847), 3 parts, 206. as translated in Frederick Gregory, Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany (1977), 64.

Everything is like a purse—there may be money in it, and we can generally say by the feel of it whether there is or is not. Sometimes, however, we must turn it inside out before we can be quite sure whether there is anything in it or no. When I have turned a proposition inside out, put it to stand on its head, and shaken it, I have often been surprised to find how much came out of it.

Samuel Butler, Henry Festing Jones (ed.), The Note-Books of Samuel Butler (1917), 222.

Facts were never pleasing to him. He acquired them with reluctance and got rid of them with relief. He was never on terms with them until he had stood them on their heads.

The Greenwood Hat (1937), 55.

For centuries we have dreamt of flying; recently we made that come true: we have always hankered for speed; now we have speeds greater than we can stand: we wanted to speak to far parts of the Earth; we can: we wanted to explore the sea bottom; we have: and so on, and so on. And, too, we wanted the power to smash our enemies utterly; we have it. If we had truly wanted peace, we should have had that as well. But true peace has never been one of the genuine dreams—we have got little further than preaching against war in order to appease out consciences.

The Outward Urge (1959)

For me too, the periodic table was a passion. ... As a boy, I stood in front of the display for hours, thinking how wonderful it was that each of those metal foils and jars of gas had its own distinct personality.

[Referring to the periodic table display in the Science Museum, London, with element samples in bottles]

[Referring to the periodic table display in the Science Museum, London, with element samples in bottles]

Letter to Oliver Sacks. Quoted in Oliver Sacks, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001), footnote, 203.

For three days now this angel, almost too heavenly for earth has been my fiancée … Life stands before me like an eternal spring with new and brilliant colours. Upon his engagement to Johanne Osthof of Brunswick; they married 9 Oct 1805.

Letter to Farkas Wolfgang Bolyai (1804). Quoted in Stephen Hawking, God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs (2005), 567.

For three million years we were hunter-gatherers, and it was through the evolutionary pressures of that way of life that a brain so adaptable and so creative eventually emerged. Today we stand with the brains of hunter-gatherers in our heads, looking out on a modern world made comfortable for some by the fruits of human inventiveness, and made miserable for others by the scandal of deprivation in the midst of plenty.

Co-author with American science writer Roger Amos Lewin (1946), Origins: What New Discoveries Reveal about the Emergence of our Species and its Possible Future (1977), 249.

Formerly one sought the feeling of the grandeur of man by pointing to his divine origin: this has now become a forbidden way, for at its portal stands the ape, together with other gruesome beasts, grinning knowingly as if to say: no further in this direction! One therefore now tries the opposite direction: the way mankind is going shall serve as proof of his grandeur and kinship with God. Alas this, too, is vain! At the end of this way stands the funeral urn of the last man and gravedigger (with the inscription “nihil humani a me alienum puto”). However high mankind may have evolved—and perhaps at the end it will stand even lower than at the beginning!— it cannot pass over into a higher order, as little as the ant and the earwig can at the end of its “earthly course” rise up to kinship with God and eternal life. The becoming drags the has-been along behind it: why should an exception to this eternal spectacle be made on behalf of some little star or for any little species upon it! Away with such sentimentalities!

Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality (1881), trans. R. J. Hollingdale (1982), 32.

Geometry seems to stand for all that is practical, poetry for all that is visionary, but in the kingdom of the imagination you will find them close akin, and they should go together as a precious heritage to every youth.

From The Proceedings of the Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club, reprinted in School Review (1898), 6 114.

Give me a place to stand, and I will move the earth.

F. Hultsch (ed.) Pappus Alexandrinus: Collectio (1876-8), Vol. 3, book 8, section 10, ix.

Have you ever watched an eagle held captive in a zoo, fat and plump and full of food and safe from danger too?

Then have you seen another wheeling high up in the sky, thin and hard and battle-scarred, but free to soar and fly?

Well, which have you pitied the caged one or his brother? Though safe and warm from foe or storm, the captive, not the other!

There’s something of the eagle in climbers, don’t you see; a secret thing, perhaps the soul, that clamors to be free.

It’s a different sort of freedom from the kind we often mean, not free to work and eat and sleep and live in peace serene.

But freedom like a wild thing to leap and soar and strive, to struggle with the icy blast, to really be alive.

That’s why we climb the mountain’s peak from which the cloud-veils flow, to stand and watch the eagle fly, and soar, and wheel... below...

Then have you seen another wheeling high up in the sky, thin and hard and battle-scarred, but free to soar and fly?

Well, which have you pitied the caged one or his brother? Though safe and warm from foe or storm, the captive, not the other!

There’s something of the eagle in climbers, don’t you see; a secret thing, perhaps the soul, that clamors to be free.

It’s a different sort of freedom from the kind we often mean, not free to work and eat and sleep and live in peace serene.

But freedom like a wild thing to leap and soar and strive, to struggle with the icy blast, to really be alive.

That’s why we climb the mountain’s peak from which the cloud-veils flow, to stand and watch the eagle fly, and soar, and wheel... below...

…...

He who designs an unsafe structure or an inoperative machine is a bad Engineer; he who designs them so that they are safe and operative, but needlessly expensive, is a poor Engineer, and … he who does the best work at lowest cost sooner or later stands at the top of his profession.

From Address on 'Industrial Engineering' at Purdue University (24 Feb 1905). Reprinted by Yale & Towne Mfg Co of New York and Stamford, Conn. for the use of students in its works.

He who wishes to explain Generation must take for his theme the organic body and its constituent parts, and philosophize about them; he must show how these parts originated, and how they came to be in that relation in which they stand to each other. But he who learns to know a thing not only from its phenomena, but also its reasons and causes; and who, therefore, not by the phenomena merely, but by these also, is compelled to say: “The thing must be so, and it cannot be otherwise; it is necessarily of such a character; it must have such qualities; it is impossible for it to possess others”—understands the thing not only historically but truly philosophically, and he has a philosophic knowledge of it. Our own Theory of Generation is to be such a philosphic comprehension of an organic body, a very different one from one merely historical. (1764)

Quoted as an epigraph to Chap. 2, in Ernst Haeckel, The Evolution of Man, (1886), Vol 1, 25.

Heat may be considered, either in respect of its quantity, or of its intensity. Thus two lbs. of water, equally heated, must contain double the quantity that one of them does, though the thermometer applied to them separately, or together, stands at precisely the same point, because it requires double the time to heat two lbs. as it does to heat one.

In Alexander Law, Notes of Black's Lectures, vol. 1, 5. Cited in Charles Coulston Gillispie, Dictionary of Scientific Biography: Volumes 1-2 (1981), 178.

Hence, wherever we meet with vital phenomena that present the two aspects, physical and psychical there naturally arises a question as to the relations in which these aspects stand to each other.

History warns us … that it is the customary fate of new truths to begin as heresies and to end as superstitions; and, as matters now stand, it is hardly rash to anticipate that, in another twenty years, the new generation, educated under the influences of the present day, will be in danger of accepting the main doctrines of the “Origin of Species,” with as little reflection, and it may be with as little justification, as so many of our contemporaries, twenty years ago, rejected them.

'The Coming of Age of the Origin of Species' (1880). In Collected Essays, Vol. 2: Darwiniana (1893), 229.

How hard to realize that every camp of men or beast has this glorious starry firmament for a roof! … In such places standing alone on the mountain-top it is easy to realize that whatever special nests we make—leaves and moss like the marmots and birds, or tents or piled stone—we all dwell in a house of one room—the world with the firmament for its roof—and are sailing the celestial spaces without leaving any track.

Journal Entry, written while camping on top of Quarry Mountain, seven or eight miles from the front of Muir Glacier, Alaska (18 Jul 1890). In John Muir and Linnie Marsh Wolfe (ed.), John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir (1938, 1979), 321.

How many and how curious problems concern the commonest of the sea-snails creeping over the wet sea-weed! In how many points of view may its history be considered! There are its origin and development, the mystery of its generation, the phenomena of its growth, all concerning each apparently insignificant individual; there is the history of the species, the value of its distinctive marks, the features which link it with the higher and lower creatures, the reason why it takes its stand where we place it in the scale of creation, the course of its distribution, the causes of its diffusion, its antiquity or novelty, the mystery (deepest of mysteries) of its first appearance, the changes of the outline of continents and of oceans which have taken place since its advent, and their influence on its own wanderings.

On the Natural History of European Seas. In George Wilson and Archibald Geikie, Memoir of Edward Forbes F.R.S. (1861), 547-8.

Human consciousness is just about the last surviving mystery. A mystery is a phenomenon that people don’t know how to think about—yet. There have been other great mysteries: the mystery of the origin of the universe, the mystery of life and reproduction, the mystery of the design to be found in nature, the mysteries of time, space, and gravity. These were not just areas of scientific ignorance, but of utter bafflement and wonder. We do not yet have the final answers to any of the questions of cosmology and particle physics, molecular genetics and evolutionary theory, but we do know how to think about them. The mysteries haven't vanished, but they have been tamed. They no longer overwhelm our efforts to think about the phenomena, because now we know how to tell the misbegotten questions from the right questions, and even if we turn out to be dead wrong about some of the currently accepted answers, we know how to go about looking for better answers. With consciousness, however, we are still in a terrible muddle. Consciousness stands alone today as a topic that often leaves even the most sophisticated thinkers tongue-tied and confused. And, as with all the earlier mysteries, there are many who insist—and hope—that there will never be a demystification of consciousness.

Consciousness Explained (1991), 21-22.

Humanity stands ... before a great problem of finding new raw materials and new sources of energy that shall never become exhausted. In the meantime we must not waste what we have, but must leave as much as possible for coming generations.

Chemistry in Modern Life (1925), trans. Clifford Shattuck-Leonard, vii.

I am coming more and more to the conviction that the necessity of our geometry cannot be proved, at least neither by, nor for, the human intelligence … One would have to rank geometry not with arithmetic, which stands a priori, but approximately with mechanics.

From Letter (28 Apr 1817) to Olbers, as quoted in Guy Waldo Dunnington, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Titan of Science: A Study of His Life and Work (1955), 180.

I am more and more convinced that the ant colony is not so much composed of separate individuals as that the colony is a sort of individual, and each ant like a loose cell in it. Our own blood stream, for instance, contains hosts of white corpuscles which differ little from free-swimming amoebae. When bacteria invade the blood stream, the white corpuscles, like the ants defending the nest, are drawn mechanically to the infected spot, and will die defending the human cell colony. I admit that the comparison is imperfect, but the attempt to liken the individual human warrior to the individual ant in battle is even more inaccurate and misleading. The colony of ants with its component numbers stands half way, as a mechanical, intuitive, and psychical phenomenon, between our bodies as a collection of cells with separate functions and our armies made up of obedient privates. Until one learns both to deny real individual initiative to the single ant, and at the same time to divorce one's mind from the persuasion that the colony has a headquarters which directs activity … one can make nothing but pretty fallacies out of the polity of the ant heap.

In An Almanac for Moderns (1935), 121

I am pessimistic about the human race because it is too ingenious for its own good. Our approach to nature is to beat it into submission. We would stand a better chance of survival if we accommodated ourselves to this planet and viewed it appreciatively instead of skeptically and dictatorially.

Epigraph in Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (1962), vii.

I believe television is going to be the test of the modern world, and that in this new opportunity to see beyond the range of our vision we shall discover either a new and unbearable disturbance of the general peace or a saving radiance in the sky. We shall stand or fall by television—of that I am quite sure

In 'Removal' (Jul 1938), collected in One Man's Meat (1942), 3.

I cannot judge my work while I am doing it. I have to do as painters do, stand back and view it from a distance, but not too great a distance. How great? Guess.

Quoted without citation in W.H. Auden and L. Kronenberger (eds.) The Viking Book of Aphorisms (1966), 291. Webmaster has tried without success to locate a primary source. Can you help?

I do not value any view of the universe into which man and the institutions of man enter very largely and absorb much of the attention. Man is but the place where I stand, and the prospect hence is infinite.

Journal, April 2, 1852.

I experimented with all possible maneuvers—loops, somersaults and barrel rolls. I stood upside down on one finger and burst out laughing, a shrill, distorted laugh. Nothing I did altered the automatic rhythm of the air. Delivered from gravity and buoyancy, I flew around in space.

Describing his early test (1943) in the Mediterranean Sea of the Aqua-Lung he co-invented.

Describing his early test (1943) in the Mediterranean Sea of the Aqua-Lung he co-invented.

Quoted in 'Sport: Poet of the Depths', Time (28 Mar 1960)

I had made up my mind to find that for which I was searching even if it required the remainder of my life. After innumerable failures I finally uncovered the principle for which I was searching, and I was astounded at its simplicity. I was still more astounded to discover the principle I had revealed not only beneficial in the construction of a mechanical hearing aid but it served as well as means of sending the sound of the voice over a wire. Another discovery which came out of my investigation was the fact that when a man gives his order to produce a definite result and stands by that order it seems to have the effect of giving him what might be termed a second sight which enables him to see right through ordinary problems. What this power is I cannot say; all I know is that it exists and it becomes available only when a man is in that state of mind in which he knows exactly what he wants and is fully determined not to quit until he finds it.

As quoted, without citation, in Mack R. Douglas, Making a Habit of Success: How to Make a Habit of Succeeding, How to Win With High Self-Esteem (1966, 1994), 38. Note: Webmaster is dubious of a quote which seems to appear in only one source, without a citation, decades after Bell’s death. If you know a primary source, please contact Webmaster.

I have long recognized the theory and aesthetic of such comprehensive display: show everything and incite wonder by sheer variety. But I had never realized how power fully the decor of a cabinet museum can promote this goal until I saw the Dublin [Natural History Museum] fixtures redone right ... The exuberance is all of one piece–organic and architectural. I write this essay to offer my warmest congratulations to the Dublin Museum for choosing preservation–a decision not only scientifically right, but also ethically sound and decidedly courageous. The avant-garde is not an exclusive locus of courage; a principled stand within a reconstituted rear unit may call down just as much ridicule and demand equal fortitude. Crowds do not always rush off in admirable or defendable directions.

…...

I have taken the stand that nobody can be always wrong, but it does seem to me that I have approximated so highly that I am nothing short of a negative genius.

Wild Talents (1932). In The Complete Books of Charles Fort (1975), 1037.

I intend to interpret Tuscarora values, beliefs, and institutions not as relics of the past, not as a step on the acculturation ladder to the successful emulation of White culture … but as a viable way of life that can stand on its own as an alternative among other American life styles.

Expressing his aim as author in Tuscarora: A History (2012), 27-28.

I know that I am mortal by nature, and ephemeral; but when I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies I no longer touch earth with my feet: I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia, food of the gods.

— Ptolemy

Epigram. Almagest. In Owen Gingerich, The Eye of Heaven: Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler (1993), 4.

I read in the proof sheets of Hardy on Ramanujan: “As someone said, each of the positive integers was one of his personal friends.” My reaction was, “I wonder who said that; I wish I had.” In the next proof-sheets I read (what now stands), “It was Littlewood who said…”. What had happened was that Hardy had received the remark in silence and with poker face, and I wrote it off as a dud.

In Béla Bollobás (ed.), Littlewood’s Miscellany, (1986), 61.

I regard sex as the central problem of life. And now that the problem of religion has practically been settled, and that the problem of labor has at least been placed on a practical foundation, the question of sex—with the racial questions that rest on it—stands before the coming generations as the chief problem for solution. Sex lies at the root of life, and we can never learn to reverence life until we know how to understand sex.

Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897), Vol. 1, xxx.

I remember working out a blueprint for my future when I was twelve years old I resolved first to make enough money so I'd never be stopped from finishing anything; second, that to accumulate money in a hurry—and I was in a hurry—I'd have to invent something that people wanted. And third, that if I ever was going to stand on my own feet, I'd have to leave home.

In Sidney Shalett, 'Aviation’s Stormy Genius', Saturday Evening Post (13 Oct 1956), 229, No. 15, 26 & 155

I searched along the changing edge

Where, sky-pierced now the cloud had broken.

I saw no bird, no blade of wing,

No song was spoken.

I stood, my eyes turned upward still

And drank the air and breathed the light.

Then, like a hawk upon the wind,

I climbed the sky, I made the flight.

Where, sky-pierced now the cloud had broken.

I saw no bird, no blade of wing,

No song was spoken.

I stood, my eyes turned upward still

And drank the air and breathed the light.

Then, like a hawk upon the wind,

I climbed the sky, I made the flight.

…...

I stand almost with the others. They believe the world was made for man, I believe it likely that it was made for man; they think there is proof, astronomical mainly, that it was made for man, I think there is evidence only, not proof, that it was made for him. It is too early, yet, to arrange the verdict, the returns are not all in. When they are all in, I think that they will show that the world was made for man; but we must not hurry, we must patiently wait till they are all in.

Attributed.

I stand before you as somebody who is both physicist and a priest, and I want to hold together my scientific and my religious insights and experiences . I want to hold them together, as far as I am able, without dishonesty and without compartmentalism. I don’t want to be a priest on Sunday and a physicist on Monday; I want to be both on both days.

…...

I stand in favor of using seeds and products that have a proven track record. … There is a big gap between what the facts are, and what the perceptions are. … I mean “genetically modified” sounds Frankensteinish. Drought-resistant sounds really like something you’d want.

Speech at Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) convention, San Diego (Jun 2014). Audio on AgWired website.

I started studying law, but this I could stand just for one semester. I couldn’t stand more. Then I studied languages and literature for two years. After two years I passed an examination with the result I have a teaching certificate for Latin and Hungarian for the lower classes of the gymnasium, for kids from 10 to 14. I never made use of this teaching certificate. And then I came to philosophy, physics, and mathematics. In fact, I came to mathematics indirectly. I was really more interested in physics and philosophy and thought about those. It is a little shortened but not quite wrong to say: I thought I am not good enough for physics and I am too good for philosophy. Mathematics is in between.

From interview on his 90th birthday. In D J Albers and G L Alexanderson (eds.), Mathematical People: Profiles and Interviews (1985), 245-254.

I then shouted into M [the mouthpiece] the following sentence: “Mr. Watson—Come here—I want to see you.” To my delight he came and declared that he had heard and understood what I said. I asked him to repeat the words. He answered “You said—‘Mr. Watson—-come here—I want to see you.’” We then changed places and I listened at S [the reed receiver] while Mr. Watson read a few passages from a book into the mouth piece M. It was certainly the case that articulate sounds proceeded from S. The effect was loud but indistinct and muffled. If I had read beforehand the passage given by Mr. Watson I should have recognized every word. As it was I could not make out the sense—but an occasional word here and there was quite distinct. I made out “to” and “out” and “further”; and finally the sentence “Mr. Bell do you understand what I say? Do—you—un—der—stand—what—I—say” came quite clearly and intelligibly. No sound was audible when the armature S was removed.

Notebook, 'Experiments made by A. Graham Bell, vol. I'. Entry for 10 March 1876. Quoted in Robert V. Bruce, Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude (1973), 181.

I think that each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest, of five hundred or a thousand acres, either in one body or several, where a stick should never be cut for fuel, nor for the navy, nor to make wagons, but stand and decay for higher uses—a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation. All Walden Wood might have been reserved, with Walden in the midst of it.

In Wild Fruits: Thoreau’s Rediscovered Last Manuscript (2000), 238. Also appears as an epigraph after the title page.

I think that we shall have to get accustomed to the idea that we must not look upon science as a 'body of knowledge,' but rather as a system of hypotheses; that is to say, as a system of guesses or anticipations which in principle cannot be justified, but with which we work as long as they stand up to tests, and of which we are never justified in saying that we know they are 'true' or 'more or less certain' or even 'probable.'

The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959), 317.

I waited for Rob and, linking arms, we took our final steps together onto the rooftop of the world. It was 8.15 am on 24 May 2004; there was nowhere higher on the planet that we could go, the world lay at our feet. Holding each other tightly, we tried to absorb where we were. To be standing here, together, exactly three years since Rob’s cancer treatment, was nothing short of a miracle. Standing on top of Everest was more than just climbing a mountain - it was a gift of life. With Pemba and Nawang we crowded together, wrapping our arms around each other. They had been more than Sherpas, they had been our guardian angels.

— Jo Gambi

…...

I would not have it inferred ... that I am, as yet, an advocate for the hypothesis of chemical life. The doctrine of the vitality of the blood, stands in no need of aid from that speculative source. If it did, I would certainly abandon it. For, notwithstanding the fashionableness of the hypothesis in Europe, and the ascendancy it has gained over some minds in this country [USA], it will require stubborn facts to convince me that man with all his corporeal and intellectual attributes is nothing but hydro-phosphorated oxyde of azote ... When the chemist declares, that the same laws which direct the crystallization of spars, nitre and Glauber's salts, direct also the crystallization of man, he must pardon me if I neither understand him, nor believe him.

Medical Theses (1805), 391-2, footnote.

I’m very intense in my work. At any given moment, I think I know the answer to some problem, and that I’m right. Since science is the only self-correcting human institution I know of, you should not be frightened to take an extreme stand, if that causes the stand to be examined more thoroughly than it might be if you are circumspect. I’ve always been positive about the value of the Hubble constant, knowing full well that it probably isn’t solved.

As quoted in John Noble Wilford, 'Sizing up the Cosmos: An Astronomers Quest', New York Times (12 Mar 1991), C10.

If I have not seen as far as others, it is because giants were standing on my shoulders.

As quoted, previously on webpage with short bio of Hal Abelson at publicknowledge.org (as archived from Nov 2004).

If it were not for our conception of weights and measures we would stand in awe of the firefly as we do before the sun.

In Kahlil Gibran: The Collected Works (2007), 204.

If somebody’d said before the flight, “Are you going to get carried away looking at the earth from the moon?” I would have say, “No, no way.” But yet when I first looked back at the earth, standing on the moon, I cried.

…...

If this [human kind’s extinction] happens I venture to hope that we shall not have destroyed the rat, an animal of considerable enterprise which stands as good a chance as any … of evolving toward intelligence.

In The Inequality of Man: And Other Essays (1937), 143.

If to-day you ask a physicist what he has finally made out the æther or the electron to be, the answer will not be a description in terms of billiard balls or fly-wheels or anything concrete; he will point instead to a number of symbols and a set of mathematical equations which they satisfy. What do the symbols stand for? The mysterious reply is given that physics is indifferent to that; it has no means of probing beneath the symbolism. To understand the phenomena of the physical world it is necessary to know the equations which the symbols obey but not the nature of that which is being symbolised. …this newer outlook has modified the challenge from the material to the spiritual world.

Swarthmore Lecture (1929) at Friends’ House, London, printed in Science and the Unseen World (1929), 30.

If you disregard the very simplest cases, there is in all of mathematics not a single infinite series whose sum has been rigorously determined. In other words, the most important parts of mathematics stand without a foundation.

In Letter to a friend, as quoted in George Finlay Simmons, Calculus Gems (1992), 188.

If you want to achieve conservation, the first thing you have to do is persuade people that the natural world is precious, beautiful, worth saving and complex. If people don’t understand that and don’t believe that in their hearts, conservation doesn't stand a chance. That’s the first step, and that is what I do.

From interview with Michael Bond, 'It’s a Wonderful Life', New Scientist (14 Dec 2002), 176, No. 2373, 48.

In Euclid each proposition stands by itself; its connection with others is never indicated; the leading ideas contained in its proof are not stated; general principles do not exist. In modern methods, on the other hand, the greatest importance is attached to the leading thoughts which pervade the whole; and general principles, which bring whole groups of theorems under one aspect, are given rather than separate propositions. The whole tendency is toward generalization. A straight line is considered as given in its entirety, extending both ways to infinity, while Euclid is very careful never to admit anything but finite quantities. The treatment of the infinite is in fact another fundamental difference between the two methods. Euclid avoids it, in modern mathematics it is systematically introduced, for only thus is generality obtained.

In 'Geometry', Encyclopedia Britannica (9th edition).

In Japan, an exceptional dexterity that comes from eating with chopsticks … is especially useful in micro-assembly. (This … brings smiles from my colleagues, but I stand by it. Much of modern assembly is fine tweezer work, and nothing prepares for it better than eating with chopsticks from early childhood.)

In The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor (1998, 1999), 475.

In no case may we interpret an action [of an animal] as the outcome of the exercise of a higher psychical faculty, if it can be interpreted as the outcome of the exercise of one which stands lower in the psychological scale.

[Morgan's canon, the principle of parsimony in animal research.]

[Morgan's canon, the principle of parsimony in animal research.]

An Introduction to Comparative Psychology (1894), 53.

In reality, I have sometimes thought that we do not go on sufficiently slowly in the removal of diseases, and that it would he better if we proceeded with less haste, and if more were often left, to Nature than is the practice now-a-days. It is a great mistake to suppose that Nature always stands in need of the assistance of Art. If that were the case, site would have made less provision for the safety of mankind than the preservation of the species demands; seeing that there is not the least proportion between the host of existing diseases and the powers possessed by man for their removal, even in those ages wherein the healing art was at the highest pitch, and most extensively cultivated.

As quoted by Gavin Milroy in 'On the Writings of Sydenham', The Lancet (14 Nov 1846), 524.

In science men have discovered an activity of the very highest value in which they are no longer, as in art, dependent for progress upon the appearance of continually greater genius, for in science the successors stand upon the shoulders of their predecessors; where one man of supreme genius has invented a method, a thousand lesser men can apply it. … In art nothing worth doing can be done without genius; in science even a very moderate capacity can contribute to a supreme achievement.

Essay, 'The Place Of Science In A Liberal Education.' In Mysticism and Logic: and Other Essays (1919), 41.

In the bleak midwinter Frosty wind made moan, Earth stood hard as iron, Water like a stone; Snow had fallen, snow on snow, Snow on snow, In the bleak midwinter, Long ago.

…...

In the history of the discovery of zero will always stand out as one of the greatest single achievements of the human race.

Number: the Language of Science (1930), 35.

In the moment of the vernal equinox, we find ourselves standing at the threshold between winter’s chill and spring’s warmth, a testament to the resilience of life and the promise of new beginnings.

A fictional quote imagined in the style typical of a scientist (19 Mar 2024).

In the republic of scholarship everybody wants to rule, there are no aldermen there, and that is a bad thing: every general must, so to speak, draw up the plan, stand sentry, sweep out the guardroom and fetch the water; no one wants to work for the good of another.

Aphorism 80 in Notebook D (1773-1775), as translated by R.J. Hollingdale in Aphorisms (1990). Reprinted as The Waste Books (2000), 56.

Innovations, free thinking is blowing like a storm; those that stand in front of it, ignorant scholars like you, false scientists, perverse conservatives, obstinate goats, resisting mules are being crushed under the weight of these innovations. You are nothing but ants standing in front of the giants; nothing but chicks trying to challenge roaring volcanoes!

From the play Galileo Galilei (2001) .

Instead of adjusting students to docile membership in whatever group they happen to be placed, we should equip them to cope with their environment, not be adjusted to it, to be willing to stand alone, if necessary, for what is right and true.

In speech, 'Education for Creativity in the Sciences', Conference at New York University, Washington Square. As quoted by Gene Currivan in 'I.Q. Tests Called Harmful to Pupil', New York Times (16 Jun 1963), 66.

Intellect is void of affection and sees an object as it stands in the light of science, cool and disengaged. The intellect goes out of the individual, floats over its own personality, and regards it as a fact, and not as I and mine.

From 'Intellect', collected in The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1903), 326.