(source)

(source)

|

G. H. Hardy

(7 Feb 1877 - 1 Dec 1947)

English pure mathematician who made leading contributions in analysis and number theory.

|

Science Quotes by G. H. Hardy (64 quotes)

>> Click for G. H. Hardy Quotes on | Mathematician | Mathematics | Ramanujan_Srinivasa | Theorem | Work |

>> Click for G. H. Hardy Quotes on | Mathematician | Mathematics | Ramanujan_Srinivasa | Theorem | Work |

[I was advised] to read Jordan's 'Cours d'analyse'; and I shall never forget the astonishment with which I read that remarkable work, the first inspiration for so many mathematicians of my generation, and learnt for the first time as I read it what mathematics really meant.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 23.

[P]ure mathematics is on the whole distinctly more useful than applied. For what is useful above all is technique, and mathematical technique is taught mainly through pure mathematics.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 134.

[Regarding mathematics,] there are now few studies more generally recognized, for good reasons or bad, as profitable and praiseworthy. This may be true; indeed it is probable, since the sensational triumphs of Einstein, that stellar astronomy and atomic physics are the only sciences which stand higher in popular estimation.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 63-64.

A chess problem is genuine mathematics, but it is in some way “trivial” mathematics. However, ingenious and intricate, however original and surprising the moves, there is something essential lacking. Chess problems are unimportant. The best mathematics is serious as well as beautiful—“important” if you like, but the word is very ambiguous, and “serious” expresses what I mean much better.

— G. H. Hardy

'A Mathematician's Apology', in James Roy Newman, The World of Mathematics (2000), 2029.

A man who sets out to justify his existence and his activities has to distinguish two different questions. The first is whether the work which he does is worth doing; and the second is why he does it (whatever its value may be).

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 66.

A man’s first duty, a young man’s at any rate, is to be ambitious … the noblest ambition is that of leaving behind one something of permanent value.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 77.

A mathematical proof should resemble a simple and clear-cut constellation, not a scattered cluster in the Milky Way.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 2012), 113.

A mathematician … has no material to work with but ideas, and so his patterns are likely to last longer, since ideas wear less with time than words.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 84.

A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 84.

A painter makes patterns with shapes and colours, a poet with words. A painting may embody an “idea,” but the idea is usually commonplace and unimportant. In poetry, ideas count for a good deal more; but, as Housman insisted, the importance of ideas in poetry is habitually exaggerated. … The poverty of ideas seems hardly to affect the beauty of the verbal pattern. A mathematician, on the other hand, has no material to work with but ideas, and so his patterns are likely to last longer, since ideas wear less with time than words.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 2012), 84-85.

A science is said to be useful if its development tends to accentuate the existing inequalities in the distribution of wealth, or more directly promotes the destruction of human life.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 113. Note that Hardy wrote these words while World War II was raging.

A science or an art may be said to be “useful” if its development increases, even indirectly, the material well-being and comfort of men, it promotes happiness, using that word in a crude and commonplace way.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 115.

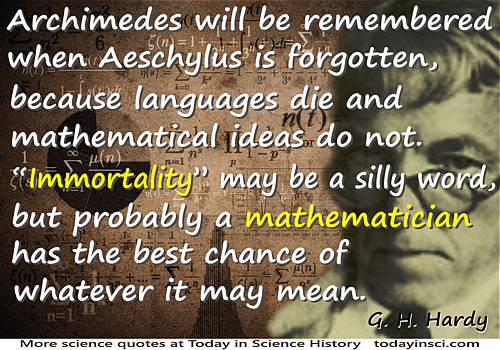

Archimedes will be remembered when Aeschylus is forgotten, because languages die and mathematical ideas do not. “Immortality” may be a silly word, but probably a mathematician has the best chance of whatever it may mean.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 81.

As history proves abundantly, mathematical achievement, whatever its intrinsic worth, is the most enduring of all.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 80.

As Littlewood said to me once [of the ancient Greeks], they are not clever school boys or “scholarship candidates,” but “Fellows of another college.”

— G. H. Hardy

Quoted in G. H. Hardy, A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 1992), 81.

Beauty is the first test: there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 85.

Chess problems are the hymn-tunes of mathematics.

— G. H. Hardy

'A Mathematician's Apology', in James Roy Newman, The World of Mathematics (2000), 2028.

Everything is what it is, and not another thing.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 109.

For any serious purpose, intelligence is a very minor gift.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 47.

Good work is no done by “humble” men. It is one of the first duties of a professor, for example, in any subject, to exaggerate a little both the importance of his subject and his own importance in it. A man who is always asking “Is what I do worth while?” and “Am I the right person to do it?” will always be ineffective himself and a discouragement to others. He must shut his eyes a little and think a little more of his subject and himself than they deserve. This is not too difficult: it is harder not to make his subject and himself ridiculous by shutting his eyes too tightly.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 66.

Greek mathematics is the real thing. The Greeks first spoke a language which modern mathematicians can understand… So Greek mathematics is ‘permanent’, more permanent even than Greek literature.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 81.

He adhered, with a severity most unusual in Indians resident in England, to the religious observances of his caste; but his religion was a matter of observance and not of intellectual conviction, and I remember well his telling me (much to my surprise) that all religions seemed to him more or less equally true.

— G. H. Hardy

In obituary notice by G.H. Hardy in the Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (2) (1921), 19, xl—lviii. Reprinted in G.H. Hardy, P.V. Seshu Aiyar and B.M. Wilson (eds.) Collected Papers of Srinivasa Ramanujan (1927), xxxi.

I am interested in mathematics only as a creative art.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 115.

I believe that mathematical reality lies outside us, that our function is to discover or observe it, and that the theorems which we prove, and which we describe grandiloquently as our “creations,” are simply the notes of our observations.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 113.

I count Maxwell and Einstein, Eddington and Dirac, among “real” mathematicians. The great modern achievements of applied mathematics have been in relativity and quantum mechanics, and these subjects are at present at any rate, almost as “useless” as the theory of numbers.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 131.

I do not remember having felt, as a boy, any passion for mathematics, and such notions as I may have had of the career of a mathematician were far from noble. I thought of mathematics in terms of examinations and scholarships: I wanted to beat other boys, and this seemed to be the way in which I could do so most decisively.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 144.

I have never done anything 'useful'. No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world... Judged by all practical standards, the value of my mathematical life is nil; and outside mathematics it is trivial anyhow. I have just one chance of escaping a verdict of complete triviality, that I may be judged to have created something worth creating. And that I have created something is undeniable: the question is about its value.

— G. H. Hardy

A Mathematician's Apology (1940), 90-1.

I have never done anything “useful.” No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world... Judged by all practical standards, the value of my mathematical life is nil; and outside mathematics it is trivial anyhow. I have just one chance of escaping a verdict of complete triviality, that I may be judged to have created something worth creating. And that I have created something is undeniable: the question is about its value. [The things I have added to knowledge do not differ from] the creations of the other artists, great or small, who have left some kind of memorial beind them.

— G. H. Hardy

Concluding remarks in A Mathmatician's Apology (1940, 2012), 150-151.

I propose to put forward an apology for mathematics; and I may be told that it needs none, since there are now few studies more generally recognized, for good reasons or bad, as profitable and praiseworthy.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 63-64.

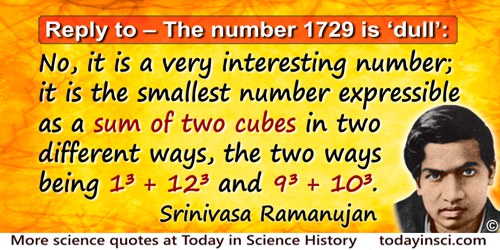

I remember once going to see him when he was lying ill at Putney. I had ridden in taxi cab number 1729 and remarked that the number seemed to me rather a dull one, and that I hoped it was not an unfavorable omen. “No,” he replied, “it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways.”

— G. H. Hardy

Quoted in G.H. Hardy, Ramanujan; Twelve Lectures on Subjects Suggested by his Life and Work (1940, reprint 1999), 12.

I was at my best at a little past forty, when I was a professor at Oxford.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 148.

I wrote a great deal during the next ten [early] years,but very little of any importance; there are not more than four or five papers which I can still remember with some satisfaction.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 147.

If a man is in any sense a real mathematician, then it is a hundred to one that his mathematics will be far better than anything else he can do, and that it would be silly if he surrendered any decent opportunity of exercising his one talent in order to do undistinguished work in other fields. Such a sacrifice could be justified only by economic necessity of age.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 70.

If intellectual curiosity, professional pride, and ambition are the dominant incentives to research, then assuredly no one has a fairer chance of gratifying them than a mathematician.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 80.

In [great mathematics] there is a very high degree of unexpectedness, combined with inevitability and economy.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 113.

In these days of conflict between ancient and modern studies, there must surely be something to be said for a study which did not begin with Pythagoras, and will not end with Einstein, but is the oldest and the youngest of all.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 76.

It is a melancholy experience for a professional mathematician to find him writing about mathematics. The function of a mathematician is to do something, to prove new theorems, to add to mathematics, and not to talk about what he or other mathematicians have done. Statesmen despise publicists, painters despise art-critics, and physiologists, physicists, or mathematicians have usually similar feelings; there is no scorn more profound, or on the whole more justifiable, than that of men who make for the men who explain. Exposition, criticism, appreciation, is work for second-rate minds.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 61 (Hardy's opening lines after Snow's foreward).

It is hardly possible to maintain seriously that the evil done by science is not altogether outweighed by the good. For example, if ten million lives were lost in every war, the net effect of science would still have been to increase the average length of life.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 65.

It is not worth a first class man’s time to express a majority opinion. By definition, there are already enough people to do that.

— G. H. Hardy

Quoted in the foreward to A Mathematician's Apology (1941, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 46.

It is rather astonishing how little practical value scientific knowledge has for ordinary men, how dull and commonplace such of it as has value is, and how its value seems almost to vary inversely to its reputed utility.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 117-118.

Mathematics is not a contemplative but a creative subject.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 43.

Mathematics may, like poetry or music, “promote and sustain a lofty habit of mind.”

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 116.

No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician’s Apology (1941, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 150.

No mathematician should ever allow him to forget that mathematics, more than any other art or science, is a young man's game. … Galois died at twenty-one, Abel at twenty-seven, Ramanujan at thirty-three, Riemann at forty. There have been men who have done great work later; … [but] I do not know of a single instance of a major mathematical advance initiated by a man past fifty. … A mathematician may still be competent enough at sixty, but it is useless to expect him to have original ideas.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1941, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 70-71.

No mathematician should ever allow himself to forget that mathematics, more than any other art or science, is a young man's game.

— G. H. Hardy

A Mathematician's Apology (1940), 10.

No one should ever be bored. … One can be horrified, or disgusted, but one can’t be bored.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 51-52.

No other subject has such clear-cut or unanimously accepted standards, and the men who are remembered are almost always the men who merit it. Mathematical fame, if you have the cash to pay for it, is one of the soundest and steadiest of investments.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 82.

Perhaps five or even ten per cent of men can do something rather well. It is a tiny minority who can do anything really well, and the number of men who can do two things well is negligible. If a man has any genuine talent, he should be ready to make almost any sacrifice in order to cultivate it to the full.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 53.

Reductio ad absurdum, which Euclid loved so much, is one of a mathematician's finest weapons. It is a far finer gambit than any chess play: a chess player may offer the sacrifice of a pawn or even a piece, but a mathematician offers the game.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 94.

Sometimes one has got to say difficult things, but one ought to say them as simply as one knows how.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 47.

The “seriousness” of a mathematical theorem lies, not in its practical consequences, which are usually negligible, but in the significance of the mathematical ideas which it connects.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 89.

The Babylonian and Assyrian civilizations have perished; Hammurabi, Sargon and Nebuchadnezzar are empty names; yet Babylonian mathematics is still interesting, and the Babylonian scale of 60 is still used in Astronomy.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 80.

The creative life [is] the only one for a serious man.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 53.

The fact is that there are few more “popular” subjects than mathematics. Most people have some appreciation of mathematics, just as most people can enjoy a pleasant tune; and there are probably more people really interested in mathematics than in music. Appearances may suggest the contrary, but there are easy explanations. Music can be used to stimulate mass emotion, while mathematics cannot; and musical incapacity is recognized (no doubt rightly) as mildly discreditable, whereas most people are so frightened of the name of mathematics that they are ready, quite unaffectedly, to exaggerate their own mathematical stupidity.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 86.

The mathematician is in much more direct contact with reality. … [Whereas] the physicist’s reality, whatever it may be, has few or none of the attributes which common sense ascribes instinctively to reality. A chair may be a collection of whirling electrons.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 128.

The mathematician's patterns … must be beautiful … Beauty is the first test; there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 85.

The mathematician's patterns, like the painter's or the poet's must be beautiful; the ideas, like the colours or the words must fit together in a harmonious way.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, reprint with Foreward by C.P. Snow 1992), 85.

The primes are the raw material out of which we have to build arithmetic, and Euclid’s theorem assures us that we have plenty of material for the task.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 99.

The public does not need to be convinced that there is something in mathematics.

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 63-65.

The study of mathematics is, if an unprofitable, a perfectly harmless and innocent occupation.

— G. H. Hardy

From Inaugural Lecture, Oxford (1920). Recalled in A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 74.

There is always more in one of Ramanujan’s formulae than meets the eye, as anyone who sets to work to verify those which look the easiest will soon discover. In some the interest lies very deep, in others comparatively near the surface; but there is not one which is not curious and entertaining.

— G. H. Hardy

Commenting on the formulae in the letters sent by Ramanujan from India, prior to going to England. Footnote in obituary notice by G.H. Hardy in the Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (2) (1921), 19, xl—lviii. The same notice was printed, with slight changes, in the Proceedings of the Royal Society (A) (1921), 94, xiii—xxix. Reprinted in G.H. Hardy, P.V. Seshu Aiyar and B.M. Wilson (eds.) Collected Papers of Srinivasa Ramanujan (1927), xxi.

What we do may be small, but it has a certain character of permanence and to have produced anything of the slightest permanent interest, whether it be a copy of verses or a geometrical theorem, is to have done something utterly beyond the powers of the vast majority of men.

— G. H. Hardy

From Inaugural Lecture, Oxford (1920). Recalled in A Mathematician’s Apology (1940, 1967), 76.

When the world is mad, a mathematician may find in mathematics an incomparable anodyne. For mathematics is, of all the arts and sciences, the most austere and the most remote, and a mathematician should be of all men the one who can most easily take refuge where, as Bertrand Russell says, “one at least of our nobler impulses can best escape from the dreary exile of

the actual world.”

— G. H. Hardy

In A Mathematician's Apology (1940, 2012), 43.

Young men should prove theorems, old men should write books.

— G. H. Hardy

Quoted by Freeman Dyson as the answer from G.H. Hardy about the book An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. Dyson, while at Cambridge, had asked him why “he spent so much time and effort writing that marvellous book when he might be doing serious mathematics.” In Freeman Dyson 'A Walk Through Ramanujan's Garden', Lecture by Dyson at Ramanujan Centenary Conference (2 Jun 1987). Collected in Selected Papers of Freeman Dyson with Commentary (1996), 189. Also as quoted in 'Mathematician, Physicist, and Writer.' Interview (Jun 1990) with Donald J. Albers, The College Mathematics Journal (Jan 1994), 25, No. 1, 4.

Quotes by others about G. H. Hardy (7)

[Godfrey H. Hardy] personified the popular idea of the absent-minded professor. But those who formed the idea that he was merely an absent-minded professor would receive a shock in conversation, where he displayed amazing vitality on every subject under the sun. ... He was interested in the game of chess, but was frankly puzzled by something in its nature which seemed to come into conflict with his mathematical principles.

In 'Prof. G. H. Hardy: A Mathematician of Genius,' Obituary The Times.

Littlewood, on Hardy’s own estimate, is the finest mathematician he has ever known. He was the man most likely to storm and smash a really deep and formidable problem; there was no one else who could command such a combination of insight, technique and power.

(1943). In Béla Bollobás, Littlewood's Miscellany (1986), Foreward, 22.

I do not think that G. H. Hardy was talking nonsense when he insisted that the mathematician was discovering rather than creating, nor was it wholly nonsense for Kepler to exult that he was thinking God's thoughts after him. The world for me is a necessary system, and in the degree to which the thinker can surrender his thought to that system and follow it, he is in a sense participating in that which is timeless or eternal.

'Reply to Lewis Edwin Hahn', The Philosophy of Brand Blanshard (1980), 901.

Replying to G. H. Hardy’s suggestion that the number of a taxi (1729) was “dull”: No, it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as a sum of two cubes in two different ways, the two ways being 1³ + 12³ and 9³ + 10³.

Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (26 May 1921).

Plenty of mathematicians, Hardy knew, could follow a step-by-step discursus unflaggingly—yet counted for nothing beside Ramanujan. Years later, he would contrive an informal scale of natural mathematical ability on which he assigned himself a 25 and Littlewood a 30. To David Hilbert, the most eminent mathematician of the day, he assigned an 80. To Ramanujan he gave 100.

In The Man who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan (1975), 226.

One day at Fenner's (the university cricket ground at Cambridge), just before the last war, G. H. Hardy and I were talking about Einstein. Hardy had met him several times, and I had recently returned from visiting him. Hardy was saying that in his lifetime there had only been two men in the world, in all the fields of human achievement, science, literature, politics, anything you like, who qualified for the Bradman class. For those not familiar with cricket, or with Hardy's personal idiom, I ought to mention that “the Bradman class” denoted the highest kind of excellence: it would include Shakespeare, Tolstoi, Newton, Archimedes, and maybe a dozen others. Well, said Hardy, there had only been two additions in his lifetime. One was Lenin and the other Einstein.

Variety of Men (1966), 87. First published in Commentary magazine.

I read in the proof sheets of Hardy on Ramanujan: “As someone said, each of the positive integers was one of his personal friends.” My reaction was, “I wonder who said that; I wish I had.” In the next proof-sheets I read (what now stands), “It was Littlewood who said…”. What had happened was that Hardy had received the remark in silence and with poker face, and I wrote it off as a dud.

In Béla Bollobás (ed.), Littlewood’s Miscellany, (1986), 61.

See also:

- 7 Feb - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Hardy's birth.

- Godfrey Harold Hardy - context of quote Languages die and mathematical ideas do not - Medium image (500 x 350 px)

- Godfrey Harold Hardy - context of quote Languages die and mathematical ideas do not - Large image (800 x 600 px)

- Godfrey Harold Hardy - context of quote Young men should prove theorems, old men should write books. - Medium image (500 x 350 px)

- Godfrey Harold Hardy - context of quote Young men should prove theorems, old men should write books. - Large image (800 x 600 px)

- A Mathematician's Apology, by G. H. Hardy. - book suggestion.

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --