(source)

(source)

|

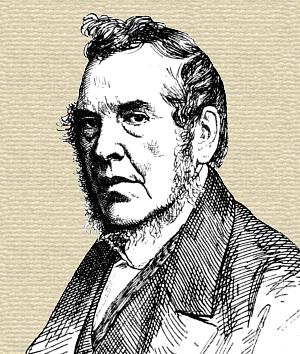

Richard Roberts

(22 Apr 1789 - 16 Mar 1864)

Welsh mechanical engineer and inventor , whose creativity spanned several fields. One of his earliest inventions was the first successful gas meter. He improved looms, invented a self-acting spinning mule for textiles, developed machines to cut screws, gears and slotting and by the 1830s was building locomotives.

|

Richard Roberts, the Inventor.

from Papers of the Manchester Literary Club

by William Henry Bailey (read 20 January 1879)

Drawn by Walter Tomlinson, from a photograph in the possession of W. H. Bailey.

[p.175] THE tapestries of ancient Babylon, the mummy cloths of Egypt, the vestments of the Cavaliers, and the robes of Queen Anne, were all spun and woven by simple tools differing little from each other—the spinning wheel, the distaff, and the rude frames called looms being the only methods known to savage or civilized man in all parts of the world for spinning and weaving until the middle of the last century. Indeed, to describe the instruments in use before this period would be to give an account, with but minute variations, of the rough expedients which are used at the present day by the natives of the Pacific islands, as well as by the more civilized peoples of India, China, and Japan.

Four names of Inventors of spinning and weaving machinery stand prominently to the front in the historical development of these important arts. I purposely omit in the interests of brevity the names of several minor inventors and contrivers. These four are— John Kay and Dr. Cartwright, the two great improvers of the loom for weaving; and Samuel Crompton and Richard Roberts, the two greatest inventors of spinning machinery. For five thousand years the shuttle had been used for weaving before John Kay, of Bury, tied a bit of string to it and thus invented the “fly” shuttle. From that moment one man could weave a wide “piece;” before that time a man had to stand on [p.176] each side of the loom, and hand the shuttle backwards and forwards. For narrow widths a weaver had to use both hands for the shuttle, but now one hand became at liberty for other work. This little but startling and wonderful invention produced one immediate result; for the power of the weaver being trebled caused a yarn famine that sharpened human wit. The yarn was used so fast as to create a dearth of it; the spinning-wheel could not keep up the supply to the great mouth of the new loom, and after a short interval of years, we find Crompton’s hand mules triumphant, producing enough yarn for the newly-fledged “fly” shuttle. But immediately afterwards came Dr. Cartwright to use more yarn and create another famine, for he invented the power-loom that could be driven by the new power—the steam-engine. Crompton’s hand spinning mule could not keep pace with the great swallowing power of the new steam loom, and then came Richard Roberts, who coupled up Crompton’s mule to the steam-engine, and thus invented what is known as the self-acting mule. He did for the mule what Dr. Cartwright did for Kay’s loom, thus enabling the steam-engine of James Watt to be used for spinning and weaving. It is the last of the four great Inventors of textile machinery, Richard Roberts, the outline of whose life and inventions I propose to sketch to night.1

To understand the peculiar genius of Richard Roberts it is necessary to recall the circumstances of the times out of which he came and in which he lived. He was born at the close of the last century, when there was coming over England one of those great waves of progress which have from time to time served to lift this country into the position it now holds before the world. Those who lived and laboured just as the wave began to rise, found themselves in the presence of a power so subtle that none were able to comprehend it in all its possibilities. It was not until some years later—not, indeed, until towards the end of the generation, that the full significance of this new force came to be apprehended, appreciated, and applied. And among the first whose sagacity taught them what steam-power really meant, was [p.177] Richard Roberts. Steam had been applied in various ways before he came actively upon the scene. First, there had been the use of pit-coal for smelting iron, then came the opening of canals, and, in 1769, James Watt took out his first patent for steam-engines, and so along these broad lines our natural progress lay— the improvement of iron manufacture, internal communication, and the application of steam. There was no longer a limited supply, but a superabundance of power, and the great problem was how to utilize it. But English commercial enterprise suffered a serious check in the long and disastrous wars that followed. When this obstacle was removed, however, by the peace of 1815, there was such a revival and expansion of trade as had never been experienced before. All the energy that had been lavished on the war was now turned in another direction. The more active natures among the population made their way to the great industrial centres, of which Manchester was the acknowledged capital. Alongside this rich development of trade, the means of internal transport and foreign communication proved miserably inadequate, and while the Government improved the condition of the roads, many thoughts were directed towards the solution of the problem how to make locomotives travel on them. The necessity of the case brought its own solution; George Stephenson cut the Gordian knot by placing his engine on the railway at Killingworth coal-pit.

In other directions the spirit of invention was abroad and busily at work, and particularly in relation to textile manufactures. It will be interesting to note how inventions in this direction proceed contemporaneously with that in others, and how at length both mingled. In 1733 James Kay invented the fly-shuttle. He had “a great many more inventions,” he says, but he did not bring them forward in consequence of the bad treatment that he had from woollen and cotton factories. In the same year, after three years’ labour, James Wyatt spun “the first thread of cotton ever produced without the intervention of human fingers,” in a small building near Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, he having copied Lewis Paul’s patent. Later on, at Wyatt’s death, Richard Arkwright, then a traveller dealing in false hair and hair dye, got hold of the details of Wyatt’s contrivance, and employed a Warrington watchmaker to construct, under his instruction, a spinning [p.178] machine.2 Arkwright, whatever may be said about his claims to honour as an inventor, certainly possessed that energy in enterprise and those business qualifications in which his predecessors had been lacking. Before his scheme was generally accepted, James Hargreaves invented his spinning-jenny, which found more favour than Arkwright’s more complicated machinery, and the manufacturers of Lancashire purchased permission to use it for £4,000.

Samuel Crompton came upon the scene in 1753, and sixteen years afterwards, while using the spinning-jenny, he heard of Arkwright’s drawing machine, and set to work to combine the two, and ultimately succeeded so well that in 1811 over forty-two millions of spindles were in operation worked by mules. Dr. Cartwright, the Kentish clergyman, followed with his steam powerlooms, which were subsequently improved by Horrocks, of Stockport, in 1813. In 1785 Watt’s steam-engine was applied to textile manufacture, and the use of this marvellous power was seen at once. Rapidly, more rapidly than they could be executed, orders flowed in upon Boulton and Watt. The impetus thus given to cotton manufacture is seen most distinctly in the number and nature of the patents for improvements in cotton-spinning and allied processes in the first quarter of the present century. In 1800 there was only one patent registered, viz., by J. S. Wood, for doubling. In 1803 there were two for spinning and reeling, and preparing and dressing cotton warps. In the following year there were five improvements patented, and in the next two years only three, while in 1807 there were five, four of which were in spinning. Down to 1815 there were fifteen. In the next five years there were ten, while in 1823 alone there were the same number. In 1824 there were six, and in 1825 there were again fifteen. In these latter years we first come upon Richard Roberts [p.179] as a patentee and as a man of some note, at any rate in Manchester, and we may well take a new departure now and trace his life up to this period.

Richard Roberts was born in the year 1789, at Carreghova, in the parish of Llanymynech, North Wales, situated about six miles from Oswestry and the same distance from Welshpool. His father, old Roberts, was a shoemaker, an intelligent man. Tradition says that he was a severe, not to say tyrannical, father, but there is no reason to believe that he entirely neglected his son’s education; for though it may be true that young Roberts never attended school in his life, there are no grounds for supposing that his father did not teach him what he could. Roberts as a boy was employed in mines and stone quarries in the neighbourhood, and at one time pulled a boat on a canal. At still another period he was engaged to a gentleman who had a pole-lathe. Richard frequently worked at this, and acquired considerable skill as a wood turner. It seems that as a boy his first display of a mechanical bent of mind was indicated by his making for his mother a spinning-wheel. It created such astonishment among the villagers at Llanymynech as to induce some of them to start a subscription, with a view of presenting him with a tool chest. With these tools he made another spinning-wheel, which old folks in the neighbourhood yet talk about as a wonderful work of art. It was inlaid with many woods, and was a beautiful piece of work. This one was raffled at the Cross Guns, and is yet, I am told, in possession of a family in the neighbourhood. At the lead mines near his birthplace there were a number of Boulton and Watt’s engines at work, and it may fairly be supposed that a lad of such a mechanical turn would be familiar with them. Hence it would be here, in this remote village, that the man whose inventive genius was to shed such large benefit upon the world would have his faculties first stirred; just as it happened to George Stephenson in the North

At length the village which had given him birth afforded no longer the requisite scope for his energies, and he proceeded to the famous Bradley Ironworks, near Bilston, and worked for Mr. John Wilkinson. His new master was a man of great mechanical skill. He was the first who could bore an engine cylinder with anything like accuracy, and when he did accomplish [p.180] this, he relieved James Watt of his chief difficulty. Roberts’s occupation with Mr. Wilkinson was that of a patternmaker, at which he was very skilful and precise. Wilkinson was a man of great individuality. He made the first iron boat; in the year 1787 he fixed the first steam-engine in France, had the first steam-bellows for smelting, and was called the Father of the Iron Trade. It cannot be doubted that Roberts would gain much valuable experience here, as well as at the Horsley Ironworks, where he moved to next. From this latter place he removed to his native village, in consequence of having been drawn for the militia. He had to depart thence, however, to avoid arrest as a deserter, and this time he went to Liverpool, where he obtained employment as a cabinetmaker. Very soon afterwards we find him in Manchester. He arrived in the town one miserably wet night, and made his way into the White Lion Inn, then situated in Deansgate.3 He had no more money in his pocket than would suffice to pay for a glass of beer, which would entitle him to a seat. He inquired of the landlord whether he knew of anyone who wanted a man, and that worthy replied that there would be an old gentleman in during the evening who might be able to do something for him. Presently the old gentleman in question appeared, and to him Roberts addressed himself, and the result was that he was engaged. His new master was a turner, and at that time executed the best work for the cabinetmakers of the district. His shop was in Blackfriars-street, Salford. The old turner, when he met Roberts, required a man to turn a fly-wheel, and it says something for the indomitable energy of Roberts that he, without hesitation, undertook to do the work The landlord of the White Lion appeared so satisfied with the bargain, that he offered the new workman lodgings for a few nights “on trust.” On the following Monday morning the workman for whom the lathe had to be turned did not appear, not having recovered from the effects of Saturday’s dissipation. It seems that there was a very pressing order for bed-posts in course of execution, and the old master made an [p.181] attempt to go on with the work himself; but his sight was not good, and he failed. This failure was the young man’s opportunity, and he seized it. He undertook himself to do the work, and acquitted himself with such credit as to obtain the post of chief turner. The dread of being taken and made to serve in the militia once again interrupted his labours, and this time he determined to go to London. He found two companions in the persons of Lewis and Murgatroyd, and the trio walked the whole distance. There was a mutual understanding between them that whoever first obtained employment should divide his earnings with the others. Roberts secured an engagement at Maudsley’s works. Maudsley was the founder of the eminent firm of engineers and shipbuilders, and there can be no doubt that here Roberts’ mechanical skill and genius would have ample opportunity for development. Maudsley was a remarkable man in many respects. At one time he was foreman with Bramah, the inventor of the hydraulic press and certain improvements in locks. Bramah refused to pay his foreman more than thirty shillings per week, and he left and started in business for himself. He subsequently attained celebrity as the manufacturer of blocks invented by Brunel for the Royal Navy. His work was always beautifully executed. Maudsley, moreover, was the inventor of the slide rest for lathes, so that it would have been wonderful indeed if the talent of Roberts had not received a great impetus from his contact with such a man. It is certain that this was the school in which the young man received much of his best instruction, and not Roberts alone; for it is not a little remarkable that many other men who have become famous in the mechanical world emanated from the same works, among whom mention may be made of Whitworth, Nasmyth, Lewis, and Muir. Roberts did not stay very long in London. Manchester seemed to be the centre of attraction for all mechanicians at this time, and Roberts floated with the stream towards Cottonopolis. His companions, Lewis and Murgatroyd, joined him again when he established a business in Manchester, in the year 1816. Lewis, however, started on his own account subsequently, and built the large works in Stanley-street, Salford, where he carried on an extensive business until his death, when the place was sold. Roberts, too, went steadily to work. The field was wide, and the time rich in opportunity.

[p.182] When Roberts started in business in Manchester, Stephenson was busy in the north; Murdoch was introducing coal gas in the south; Sir Humphry Davy was at work in his laboratory; Mr., afterwards Sir Francis Ronalds’s electric telegraph had been rejected by the War Office;4 steamboats were being made; the Comet was plying between Glasgow and Greenock; Lardner was trying to prove that it was foolish to imagine that a steamboat could be made to cross the Atlantic; the Quarterly Review was demonstrating that a man who should travel on a railway faster than nine miles per hour might as well get straddle-legged on a Congreve rocket; and a noble lord laid down the principle that to go at a great speed with our back to the wind would cause the lungs to collapse, and that to face the wind while going at a high speed would occasion such a pressure as to make a man into a wind-bag, and “choke him beyond a doubt.” We know now where the wind-bags were.

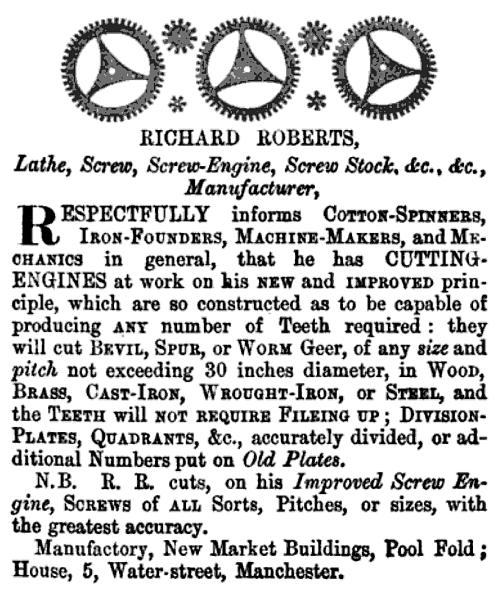

In these stirring times Roberts was busy in Water-street, Manchester, where he did mechanical work and “screw-cutting on reasonable terms.” His fly-wheel was in the cellar, and his lathe upstairs in a bedroom. The strap passed through the living room of the ground floor, and the power that turned the fly-wheel was Roberts’s first wife. His unusual skill soon became known, and his fame increased. Practically, he invented to order, for the spinners and weavers, anxious for mechanical contrivances whereby they might be more independent of manual labour, frequently sought his help. His business so much increased that it was necessary to remove to larger and more convenient premises, and we next find him working over some stables, approached by a Jacob’s ladder, in Newmarket Buildings, opposite the site now occupied by the premises of the Examiner and Times.

We next find Roberts in connection with gas lighting. Murdoch had fitted up Boulton and Watt’s works at Soho, and thence he went direct to Salford to fit up Messrs. Philip and Lee’s mill with the new light. The mill stood where the bonding-houses now [p.183] stand, in Chapel-street . After this he proceeded to erect gasworks for Manchester, and the town commissioners requested Roberts to invent a gas meter, and he did so. Mr. Clegg, of Oldham, is always mentioned as the inventor of the wet gas meter; and all I know of the subject is that it is mentioned in the records of the period that Roberts invented a meter for the town authorities. The invention of the slide lathe at this period was a great service to mechanics and engineers. Some of the first made by Roberts are still at work in Manchester; and I have heard toolmakers say that for some sorts of work they are even superior to modern tools. The carriage of the lathe, instead of being at the top of the bed, was placed on the front, hanging from a V-slide. The centres of the fast-and-loose headstocks were placed forward from the bed, towards the workman, and the consequence was that a lathe having nine-inch centres will take in a roller eighteen inches in diameter, which, of course, is not the case with the ordinary lathe now made, as the thickness of the carriage only permits smaller diameters to be turned.5 The slide lathe was closely followed by a prolific birth of other useful tools, amongst the more important being the slotting machine, which had automatic motion, and could be made to manipulate the article to be stamped or slotted with great rapidity, inasmuch as the bed was so adjusted as to be able to move in any conceivable direction. Another remarkable invention was the planing machine. The title of Roberts to be considered as the inventor of the planing machine has been very warmly contested; but, perhaps, on the whole, it may be said that by a singular coincidence the same happy thought occurred both to Roberts and to Fox of Derby, and that the machine was simultaneously invented by both of them. There was at the time a very urgent necessity for something of the kind to meet the growing demand of the engineers; for the old method of chipping and filing was every day demonstrating its total inefficiency. Roberts was often, however, heard to express his astonishment that, notwithstanding the fact that the planing machine was not patented by him, it was at work in Manchester for fourteen or fifteen years before it became customary for engineers to have them in their own shops. As [p.184] usual, necessity compelled the invention of the planing machine. Roberts made copying presses for the stationers, and one man of great strength who chipped and filed the tops and bottoms of the presses earned a great deal of money, which enabled him to have leisure, which he devoted to beer. As Roberts became disgusted with the man’s irregularities, he endeavoured to make a machine do the chipper’s work; the result was the invention of the planing machine, which, I have been told, was somewhat like an old mangle. One of that sort that required the hand-wheel to be turned in the opposite direction when it had made one stroke. The usual practice was for all but the very largest firms to send their castings to be planed to a shop where “planing and screw-cutting” were done. I recollect well one of these ancient men, known to mechanics by the name of “Old Pedley.” He was at one time in the employ of Sharp and Roberts; but, having accumulated sufficient capital to buy a machine, he began business near Ardwick Green. His machine secured him a comfortable living, though it was driven by a winch-handle, and his charge was but a halfpenny a square inch. The great importance of this invention will be seen the moment the slightest comparison is made between the results of the new and old method. With one of William Muir’s small machines, when I was an apprentice, I found it possible to plane a square foot in about twenty minutes, at a total cost, say, of sixpence; while to chip and file the same surface would occupy two days, and cost something like twelve shillings.

When in but a small way of business Roberts was an active promoter of the first Mechanics’ Institution in Manchester, and he was also one of the first members of the New Corporation of Manchester, and served as Town Councillor for some years. He was, with Dr. Dalton and others, an active member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

The first patent taken out by Roberts was in 1822, and it was for machinery for weaving plain or figured cloths, which might be used in conjunction with looms then in use; and also for certain improvements in the construction of looms for weaving plain or coloured cloths, and in the method of working looms either by hand, by steam, or other power. But here perhaps it may be mentioned there was a good deal of hand and “other power” in use at that time; for in 1790 not a single steam-engine [p.185] existed in Manchester, while in 1824 there were two hundred. Besides this, not a single loom was driven by steam power in 1814; but ten years later, so rapid was its application, more than thirty thousand looms were actively at work, whose motive power was steam.

In the year 1823, the firm of Sharp and Roberts, Atlas Works, was established as locomotive builders, toolmakers, and general machinists, to which was added the manufacture of turret clocks. Mr. Thomas Sharp was boroughreeve of Manchester and evidently a man of wealth and position. Those who are familiar with Manchester records will recollect that as boroughreeve he was compelled, in the year 1819, to caution that political mountebank, Cobbett, who had arrived from America with the bones of that much-traduced thinker, Tom Paine, in a coffin. It was feared that the presence of the bones might have caused tumult, and when Cobbett was coming on the road from Liverpool messengers conveyed the worthy boroughreeve’s advice, which was strengthened by the wise counsels from the good boroughreeve of Salford. It also appears that Cobbett intended to take the bones to Bolton, and the town crier having announced that fact, the poor man was sentenced to ten weeks’ imprisonment. The influence of the caution caused Cobbett to hesitate at Chat Moss, and to leave the main road at Irlam and go thence to London. Mr. Sharp had heard of Roberts, and had requested his assistance in the development of a reed-making machine that had been introduced by an American. Roberts could not make the machine work perfectly, but said he could invent another that would. This so pleased Sharp that he made Roberts an offer of a partnership. The capital introduced by Sharp gave full employment to the inventive faculties of Roberts, and then commenced the production of tools and locomotives, wheel-cutting engines, and turret clocks,6 the mere description of which, with their various improvements, would fill volumes. His partnership with Thomas Sharp was terminated by the death of the senior partner in 1843, and from that date Roberts carried on business at the Globe Works, Faulkner-street, as Richard Roberts and Co., and shortly afterwards [p.186] as Roberts, Fothergill, and Dobinson. This partnership ended in 1849, and he carried on business as Richard Roberts and Co. again until 1852, when he gave up business as machine maker and started as consulting engineer in Brown-street, Manchester, and afterwards at 10, Adams-street, Adelphi, where he got rid of all the money he had saved by experimenting in steamships.

In 1823, Roberts patented some improvements in steam-engines, and also in the mechanism through which the elastic force of steam was made to give impulse to and regulate the speed of locomotive carriages. These improvements were of considerable value, and consisted, in the first place, in a new form and arrangement of the working valves to allow of the entrance and escape of the steam to and from the working cylinder. Roberts saw that, supposing the steam to continue to be generated of nearly uniform density, the quantity of imparted force would be measured by the length of intervals of time during which the steam flowed uninterruptedly from the boiler into the working cylinder. For the perfect regulation of these intervals of steam supply, then, it was necessary to possess the power of cutting off the steam at any moment of the stroke, leaving the subsequent action to the expansive force of the portion of steam already admitted. This required power Roberts supplied by making one arm of the intervening lever in the working gear of the induction valve changeable at any moment. Although, as his old friend the late Mr. Bennett Woodcraft, of the Patent Office, says, Richard Roberts was the very first to take a patent out for a mode of working steam “expansively,” he cannot be considered the inventor of the idea, but only claimed the method of doing it. In the next place, he invented a self-acting regulator, consisting of a hollow metallic float, while he also improved the mechanism through which the elastic force of steam was made to give impulse to and regulate the speed of locomotive carriages, so as to allow a difference of rotatory velocity in the bearing-wheels of a locomotive carriage whilst both such wheels were being driven by a motive power common to them both. The object was to accommodate their relative velocities to the case of the path not being right-lined. The principle of the contrivance was the driving of two bearing-wheels independent of each other’s action on one axle, by a carrier common to both, which could accommodate [p.187] its action on the two wheels to any difference of rotatory velocity which they might be required occasionally to perform.

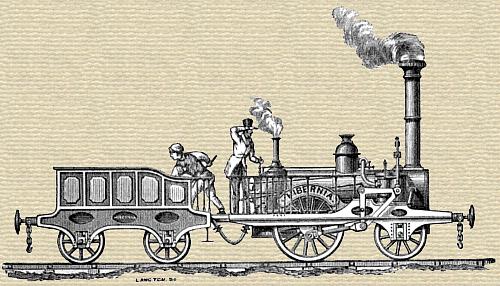

The locomotive received a great amount of attention from Richard Roberts, and many important improvements in it were introduced by him which cannot now be mentioned in detail. The drawing of the first locomotive made in Manchester has been photographed by kind permission of Mr. John Robinson, the present managing director of Sharp, Stewart, and Co.

The first locomotive made in Manchester was made by the firm for the Dublin and Kingston Railway. The locomotives afterwards made by Roberts had a great influence generally in improving their design, stability, and economical working, so much so, that even at the present day, although it has undergone so many changes, the firm but graceful outlines still bear the impress of the genius of the old mechanic.

In connection with these improvements in locomotives Roberts patented a new mode of constructing the bearing-wheels, and also a steam cylinder and piston as applied to produce pressure on the lever of a brake to retard motion. In other words, he invented a steam brake. In 1834 Sharp and Roberts conjointly patented certain improvements in machinery for spinning and doubling cotton, silk, flax, &c, consisting in a peculiar construction of the parts of a throstle-frame for spinning and doubling; [p.188] in the adaptation of upright drums, for driving the warves or whirls of both the spindles and the flyers by distinct bands in a throstle-frame; in the modes of mounting and driving the bobbins and the flyers in a throstle, for the purpose of causing them to revolve with distinct and dissimilar speeds; and in the adaptation of a spiral guide sliding round a circular head, the guide being intended to act as a flyer in a throstle-frame constructed to suit it. In the same year the partners took out a patent for machinery for grinding corn, &c. The next patent of Roberts’s is in 1844, and is for improvements in preparation and spinning machines; while three years later he patented improvements in machinery for punching and perforating metal, and in the same year some improvements in beetling and mangling machinery. The nature of his improvements in this instance consisted in the construction of a beetle or machine with one or more grooved or indented rollers for giving to woven fabrics a glossy finish similar to that then produced by the stamper in the machine known as the beetle; in the application of steam for giving pressure of the rollers; and in an improved arrangement and combination of parts of a roller-mangle, by which the required pressure is given to the fabric. In this year he also patented some improvements in machinery for preparing and spinning cotton and other fibrous substances, which were simply attempts still further to perfect his mule.

I must not omit to mention one of his great inventions which has not been alluded to, and in sufficient manner, by those who have written about the Menai tubular bridge. A tubular bridge, it will be obvious, consists of a number of plates exact duplicates of each other. Now the holes in the iron plates, when punched by an ordinary punching machine, do not always come opposite the holes of the plates to which they have to be riveted, and thus want of accuracy is often resented in a somewhat barbarous manner by a rimer which is inserted to make the way for the rivet, the result being either a hole much too large for the rivet, or a hole of such a shape as to require the insertion of the rivet in a diagonal manner, and very often resulting in great weakness and sometimes fracture of the margins of the plates, and altogether an improper finish. Roberts was requested to design a machine for punching the plates of the Menai bridge, which he [p.189] called the Jacquard punching machine. This machine, it may be said, printed holes to any pattern in the iron. The plates were punched with such perfection as to be exact duplicates of each other. Plates could be placed on each other and stacked, and bars of iron could be threaded through, so equally apart were the holes. The same machine punched the plates for the bridge erected over the St. Lawrence; and also for bridges of the Victor Emmanuel railway in Italy.

In 1848 he patented improvements applicable to clocks and other timekeepers, in the machinery for winding clocks and hoisting weights, and for effecting telegraphic communication between distant clocks and places otherwise than by electromagnetism. This specification is a most elaborate production and is equalled by one in which, in 1850, Roberts specifies and claims to have invented certain improvements in the manufacture of plain and figured fabrics—such as plushes, velvets, carpets, &c.—which are woven on wires to form loops that were subsequently cut to form the pile. In the following year his genius had taken another turn, and we find him inventing and patenting improvements in machinery for regulating and measuring the flow of fluids; for pumping, forcing, agitating, and evaporating fluids, and for obtaining motive power therefrom. From this Roberts proceeds to the perfecting of improvements in twin-screw steamboats, and generally in the constructing and propelling of vessels, which improvements he specified as exactly thirty-three in number. They related, among other things, to the construction of vessels with a passage outside the shrouds, and mode of constructing vessels so as to admit light in almost every part through openings made in the decks; the use of compartments between the chimney and its casing for ventilating purposes; the construction of hollow beams for supporting floors and ventilating apartments; the mode of constructing the bottom of vessels with cells; the improved mode of constructing as well as of casting, heaving, and fishing of anchors; the application of self-acting watertight doors to the bulk-heads; the construction of lifeboats, mechanism for lowering and raising ships’ boats, and to the improved construction and application of shields to ships of war. In 1853 Roberts patented some improvements which he had effected in the construction of [p.189] casks and other vessels. 1854 was a very prolific year, for no less than five of his specifications bear that date. The first consisted of improvements in machinery for cutting paper, pasteboard, leather, cloth, and other materials. The second consisted of improvements in machinery for the preparation of fibrous substances; the third was for improvements in machinery for punching, drilling, and riveting; the fourth was for machinery for preparing and spinning fibrous substances; and the fifth related to the preparation of fibrous materials solely. In 1856 Roberts seems to have turned his attention to omnibuses, for he patented certain improvements in that year which, to detail, would be simply to describe the modern omnibus. But perhaps one of the most remarkable instances of the scope of Roberts’s singular genius may be found in that, in 1858, he patented improvements in mechanism for engraving in line paintings and other designs, on flat and curved surfaces of metal, paper, and other materials. In 1860, about which time he removed to London, he, by himself in the first instance, and conjointly with Captain Symonds in the latter, took out two patents. The first was for improvements in punching machines; the second for improvements in marine steam-engines and in auxiliary machinery.

Richard Roberts’s greatest achievement, however, was the self-acting mule. It may be interesting, after the lapse of half a century, and since so many improvements have been made in the self-acting mule, to place on record in this place the precise character of the improvements which Roberts claimed as his. In 1825, starting with the mule then in common use, Roberts claims as his sole invention such part of his improved mule as put down the faller by the agency of a rim when turning back for the purpose of backing off, and which was effected by communicating to the rim a motion the reverse of which it possessed when giving twist to the yarn. He also claims the mode of putting down the faller by a lever; the mode of regulating the motion of the faller, and the mode of forming the cop by causing an arm or lever connected with the faller to pass longitudinally over, under, or along the surface of the shaper; the mode of changing and reversing, by means of cams, springs (or weights), and contact wheels, and the motions of the wheels, pulleys, and shafts used in twisting and backing off and for driving in and [p.191] out. In 1830 he patented, as before stated, his invention for the making of this machinery self-acting, and in 1847 he specified certain improvements upon those set forth in 1825. The first of them was to remedy the evils experienced in passing the driving-strap from the loose to the fast pulley and vice versa by substituting a “friction cone” for the fast pulley. The second consisted of means for taking out and putting up the carriage, and for working and winding an arm by toothed gear instead of by bands, scrolls, and pulleys; while the third consisted in arranging the parts of the mechanism so as to admit of the quadrant and winding-in arm being worked on a shaft, and so rendered much firmer than when on a stud. The fourth improvement consisted in the means employed to liberate the cam shaft, by which greater precision was ensured than was attained with the “long lever;” while the fifth consisted in unlatching the faller and disengaging the winding-on movements at the end of each stretch by the action of the cam shaft, whilst effecting the necessary changes for recommencing the next stretch, by which means snarls were almost entirely avoided.

It might fairly be said of Richard Roberts that he invented to order. People went to him and asked him for machinery to do work then done by hand, and he seems to have set himself to fulfil the order. This may be seen in the way in which it came to pass that he invented the self-acting mule. The steam looms which were being worked consumed the production of Crompton’s hand mule faster than the workmen could produce it. High wages were paid to spinners, who worked fewer hours for increased pay, as the colliers did during the late coal famine. The workmen feeling their power struck for still higher wages, and stopped the mills, for they commanded the whole trade, and had accumulated a considerable fund in their trade society. Weavers, dyers, finishers, bleachers, and all dependent on “twist,” were thrown out of employment by the autocrats of the trade, who earned as much money in three days as sufficed to keep them in comparative luxury for a whole week. Capitalists suffered by the continual disturbances of the turn-outs, and as famine in Egypt led to the invention of the pump, so had necessity led to the invention of the self-acting mule. Several of the leading spinners appealed to Roberts in their dilemma, but he was busy with the locomotive [p.192] then being made by his firm. Busy as he was, he at first declined to listen to the appeals made to him, but at length directed a Crompton’s hand-mule to be erected in the works that he might familiarize himself with its motions, and study how to construct one that should work automatically. The result we know. The new machine was immediately adopted by the Lancashire spinners; and in 1834 more than sixty mills, employing nearly four hundred thousand spindles, had the invention at work. In 1831, Mr. Knowles, of the Oxford Road Twist Company, Manchester, patented an improvement in mules which embodied the chief features of the Roberts “headstock;” but the Company acknowledged Mr. Roberts’s prior claim, and agreed to pay royalty on all mules made by them.

There are in existence several models of inventions by Richard Roberts presented by him to the Peel Park Museum, Salford. Amongst them are some powerful electro-magnets, which, even at this day, as at a recent meeting of telegraph engineers, have given rise to a very interesting discussion. One of these magnets, a four-inch one, will sustain a load of 1,400 lb. The radiograph was another contrivance, invented by Roberts to illustrate certain discussions at the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. This machine enables the spokes to be counted, although driven at a very high velocity. A polished cast-iron sphere is also exhibited, which was made to illustrate M. Leon Foucault’s remarkable pendulum experiment. The centrifugal railway was constructed by Roberts to illustrate centrifugal force. Mr. Roberts constructed this in order that the pupils of the Manchester Mechanics’ Institution might have the laws of centrifugal force explained to them. This centrifugal railway is a very ingenious contrivance. It is fitted with little carriages, which may be filled with water, and which, going on a railway at high speed, actually go round and round, upside down, of course, as they form the circle, without spilling the water. One of these railways was constructed on a large scale from Roberts’s model, and exhibited at the Hall of Science, Manchester, which building was until recently known as the Campfield Free Library.

At one time Roberts commenced a crusade against the shape of waggon wheels, and a model is exhibited at Peel Park Museum of a road waggon, the axles of which are adjustable to a [p.193] considerable angle from the horizontal. This model is intended to show that increase of draught, wear and tear, and destruction of roads are the consequences of depressing the ends of carriage axles. There is also a model shown of a proto-motive clock, which consists of a dial at the end of a gutta-percha tube, which may be a thousand feet long. The aim is to demonstrate that a number of such dials, in different situations, and so attached, may be made, by means of a column of air at natural pressure, to indicate the same time as a clock with which they may all be connected, the major clock in this case being at one central station, and giving a puff of air, say, every half minute. But, following up this idea, what is to prevent our stationing a huge air-compresser away in the country and forcing the fresh and balmy air into the crowded courts and alleys of great cities? The air-compresser might be placed where “ozone” is in abundance, and there receive its supply. The compression would be such as to put as much into a few inches as would fill a room when it came out of the exhaust pipe. The air, of course, would do work, if required, such as turning sewing machines and similar domestic mechanism.

Roberts, in order that he might have a proper basis for the construction of the pendulums of clocks and the balance wheels of watches, made experiments on the expansion of glass, wood, and other materials. He was led to these on finding the popular tables of the relative expansion of bodies by heat very incorrect. He made a stove, in which he could heat the rods and bars experimented upon to 130° Fahr. These rods he wrapped in listing, to prevent sudden change. They were then laid rapidly upon supports along a handrail laid in a sloping direction, on the outside of the building, one end being on a fixed stay. A screw, adapted to the 0·001 of an inch, was brought to bear on the upper end of the rod; and the time occupied in making this experiment never exceeded forty seconds. After the rods and bars cooled, the contraction was determined by turning the screw. By this means, Roberts exhibited tables that differed exceedingly from those in common use.

The late Emperor Napoleon consulted Roberts about armour clads and turret ships, and I remember seeing drawings of these before they were submitted to the Emperor, who received Roberts in person. He was also consulted by the Russian Government, [p.194] and invited to St. Petersburg by the Emperor Nicholas, to take up his residence there. During the American war of secession he designed the twin screw blockade runner, the Flora, and other vessels, which by means of independent screws could turn in her own length; this vessel was very successful and evaded all attempts at capture.

Roberts died on the 11th of March, 1864, at the age of seventy-five, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. Many of his brother engineers and his old workmen were present at the funeral, and the pall-bearers were Benjamin Fothergill, John Ramsbottom, W. Heywood, Mr. Anderson, my father (John Bailey), and Alderman Fletcher, of Salford. His daughter, married to Mr. Paul Lubbold, of London, died about three years after her father. Mr. Lubbold has placed a marble bust of the great inventor and a medallion portrait of his wife over their graves, which are side by side in the cemetery.

Roberts’s chief power lay, I should say, in his marvellous memory and his large capacity for combining forces. In his way through life, nothing bearing on the application of steam or machinery escaped his attention, and he was thus enabled to bring to bear a wide experience and a vast array of well-digested facts. He was of somewhat eccentric habits. Nevertheless, he had a genial soul, and in his days of prosperity he did not neglect those belonging to him. His integrity was conspicuous. He abhorred a lie. Scientific witnesses often have bad characters, but his was well known for truthfulness. This was publicly acknowledged by both Lord Campbell and Lord Brougham, who, on several occasions, stated they could always believe what he said. Richard Roberts loved his work for its own sake. Pecuniary reward with him was the least and last consideration. He was kind to children—probably too kind, for he spoilt his own. He would spend hours in teaching a lad how to file flat and square. His eye was perfect in its education, for my father tells me that he could file a cube of metal true on all its sides without the aid of a “square” or “ straight edge.” His manners were somewhat rough, especially to armchair engineers. He took no trouble to reduce absurdities to metaphorical language; his energetic words always were bare and undraped. If he thought a man a fool, he would say so. His humour in the shop could [p.195] generally be indicated by sound as well as demeanour, for his great face, which was the face of a starved granite lion, was very expressive, and his tune was always whistled. He would sometimes stand behind a man who was spoiling a good sixteen-inch file by rubbing it bright for two inches in the middle, and doing that like a cockboat in a storm. Roberts, carefully looking at the back of the man who thought he was a fitter, would put his hands in his breeches pockets and whistle the Dead March. This was equal to notice that the man’s “ number was stopped,” in other words, that he was discharged. When he was pleased with a man, he would whistle a lively jig or song tune.

Richard Roberts was poor when he died, and some of the mechanical papers said it was to our shame as a nation that it was so. Let justice be done, however, to those who only too late became aware of his straitened circumstances. I called upon him in London in 1861 and in 1862, and it was with some difficulty that I obtained some idea of his circumstances; but the moment it became known that he was in need a strong committee was formed, which consisted of Lord Brougham, Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth, Sir W. Fairbairn, Sir Joseph Whitworth, John Cheetham, Matthew Curtis, Charles Beyer, Edmund Ashworth, C. P. Stewart, John Ramsbottom, John Platt. Mr. David Chadwick, M.P., was, I believe, honorary secretary, and I remember the subscription list was headed by most of the gentlemen I have named with sums of £50 each. The amount promised was handsome, and in the midst of this handsome recognition, but before he could partake of it, he was taken away from us.

I have endeavoured to give some account of a man who has had an immense influence on our prosperity and comfort; a man who will be classed in future records as one of the most remarkable men of this century, crowded as its history will be with the names of great benefactors. His genius and the supremacy of his intellect caused all those contemporaries who knew him to bow to him as a great master. His old workmen always spoke of his ability with great reverence; for to them even he was a continual and fascinating surprise. He differed from the ordinary inventors whose names figure in the records of human progress, who were triumphant in some special department only after suffering and long-life devotion, for his imagination was so rich [p.196] in constructive skill that he was enabled to perfect inventions in weeks which would probably have occupied other men years of labour. Of such men it may be affirmed that the rich imagination, the facility of using the mind’s eye, the power “to give to airy nothing a local habitation and a name,” produces either a poet, a sculptor, or an inventor. It is said that it took about twelve weeks only for him to produce the first self-acting mule. The contractors for the Britannia Tubular Bridge wanted a machine to punch the plates, and he forthwith invented the Jacquard punching machine. The reed-making machine he invented to order; and probably the most extraordinary exhibition of his wonderful versatility may be seen in the way which, at sixty years of age, he went to London from Manchester, an inland town, and invented successful blockade runners of great speed, and introduced improvements in steamboats and war ships of such a nature as to astonish and delight men who had devoted all their lives to that particular branch of engineering. His designs always gave evidence of his love of the beautiful. He hated a sharp corner and uncouth design with as much cordiality as Dr. Johnson hated punsters and Scotchmen. His locomotives, his turret clocks, his self-acting mule, his steamships, his slide lathe, his carpet loom, his slotting machine, all show his power of design in their graceful proportions. In all this he has taught engineers that metal in the right place always produces the most agreeable contour; that strength and beauty always are in harmony. If Ruskin were sufficient of an economist to understand values, and had sufficient breadth of mind to know that there are other tools in the world than the ploughshare, he would have loved Richard Roberts.

I venture to claim for this great man that, although our records are crowded with the names of eminent engineers, he is the greatest mechanical inventor of the nineteenth century. I cannot but feel that justice has not been done to the memory of one whose whole life was spent in conferring benefits on the race. We have not yet here in Manchester, where he laboured for us all, any outward symbol of our gratitude and admiration. In St. Paul’s Cathedral is this inscription, dedicated to its architect: “If you seek for his monument, look around.” And, following this sentiment, it is by no means a bold statement to [p.197] make when I say that it is impossible to look at a locomotive or to go into any cotton mill or machine works in the world without finding records and evidences of the prodigious and beneficial influence and power of Richard Roberts. This city of Manchester we are proud of our very prosperity and existence is the result of original power and moral bravery; it is not only the metropolis of engineering, but it is also fast becoming the handsomest city in the north of England. The canopy of smoke which our prodigality and ignorance permits to smear and deface our architecture, will vanish at the command of the coming chemist. Shall our city be adorned with a monument to commemorate the genius and record our sense of the benefits received from the works of the old mechanician, whose deeds I have attempted to record?

The following is a fac-simile of Roberts’s advertisement, as it appeared in the first number of the Manchester Guardian, May 5, 1821, which was then printed by his friend, Mr. Jeremiah Garnett:—

1 I have for some few years past been engaged in collecting material for a life of Richard Roberts, which I hope before long to publish, and I take this opportunity of soliciting aid from those members of the Club who may be able to contribute information about the old Inventor.

2 I believe Richard Arkwright is the only man on record whose patent has been annulled by Act of Parliament. In one patent specification he seems to have written a history of the textile inventions of the previous twenty years, and to have patented it, omitting, of course, names and dates and all evidence of sources. He certainly founded the factory system by applying to it the division of labour, and such merit as that deserves should be accredited to him. But it is a different thing to the possession of original inventive and mechanical genius which has been popularly but erroneously ascribed to him.

3 The White Lion has been pulled down. Its site was right opposite the Barton Arcade. Twenty years ago it was the favourite resort of engineers and boilermakers on market days. Many would pay their accounts and give quotations there; indeed, it was a kind of Engineering Exchange.

4 The following is a copy of the official note: “Mr. Barrow presents his compliments to Mr. Ronalds, and acquaints him, with reference to his note of the 3rd inst., that telegraphs of any kind are now wholly unnecessary, and that no other than the one now in use will be adopted. Colonial Office, 5th August, 1816.”

5 One of these lathes is now at work at Messrs. Beyer, Peacock, and Co.’s works at Gorton.

6 The first turret clock designed by Roberts is fixed over the Atlas Works, in Bridgewater Street, Manchester. It was made in 1825. St. Ann’s Church clock, Manchester, and many others in the district, were made by him.

- 22 Apr - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Roberts's birth.