(source)

(source)

|

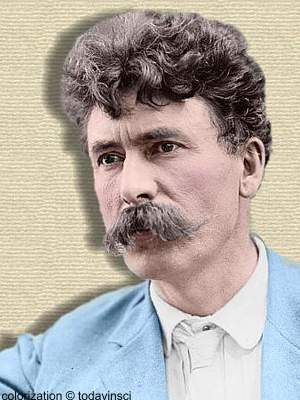

Ernest Thompson Seton

(14 Aug 1860 - 23 Oct 1946)

English-American naturalist, author and illustrator who wrote and illustrated over forty books on wild life, woodcraft, Indian lore and animal-fiction stories, aided by his detailed field observations.

|

Ernest Thompson Seton

14 Aug. 1860 - 23 Oct. 1946

naturalist, artist, writer, and lecturer, was born Ernest Evan Thompson in South Shields, England, the son of Joseph Logan Thompson, a businessman, and Alice Snowden. Joseph Thompson claimed famous Scottish ancestry, including a title, never legally established, deriving from the fifth earl of Winton, Lord Seton. Ernest legally adopted the surname Seton in 1901.

When the family shipping business failed in 1866, Joseph Thompson emigrated with his family to a Canadian farm but, within four years, sold out to a neighbor, William Blackwell. The Thompsons then moved to Toronto, but Ernest's experience with country life had already convinced him to become a naturalist. While in Toronto Collegiate High School, he became ill and was sent to stay with the Blackwells, where he recovered quickly. His famous boy's book Two Little Savages(1903) is a fictional account of his adventures there.

Returning to Toronto in 1876, Seton apprenticed himself to a portraitist, acceding to his father's wish that he become an artist. He attended the Ontario School of Art and in 1879 won a gold medal. That same year he persuaded his father to finance a trip to London, where he studied mammalian anatomy at the London Zoo and British Museum. Although he won a tuition scholarship in 1880 to the Royal Academy School of Painting and Sculpture, ill health, his periodic bane, soon forced him home in poor spirits.

Seton lived briefly on his brother's farm in Manitoba, then took up a claim of his own nearby. Unready to settle down, he spent most of the next five years trapping, drawing, collecting, and hunting on the Manitoba prairie. During these years Seton became a self-trained field researcher and was appointed naturalist to the government of Manitoba. In 1884 he was invited to join the new American Ornithologists Union by its secretary, C. Hart Merriam, and began contributing articles to its journal, the Auk.

Soon Merriam invited Seton to visit him in upstate New York. The American used one of Seton's drawings in his Mammals of the Adirondacks (1884) and later commissioned a number of them for government publications. For three years, Seton lived at intervals in New York City, working briefly for a lithographer and studying at the Art Students League. During this time, his first scientific work, A List of the Mammals of Manitoba (1886) was published, followed by The Birds of Manitoba (1891).

Through a contract to make a thousand nature drawings for the Century Dictionary (1889-1891), Seton met prominent American ornithologist Elliott Coues, the dictionary's zoological editor. Coues introduced him to J.A. Allen, William Brewster, Robert Ridgway, and other ornithologists. Because of his eccentricity and egotism, Seton repelled some colleagues of more conventional temperament. He did, however, befriend Frank M. Chapman, of the American Museum of Natural History, who gave Seton work as an illustrator and textual contributor to his Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America (1895) and Bird Life (1897).

In 1890 Seton went to Paris, where he trained at Julian's Academy. The next year, his oil painting of a sleeping wolf was chosen for display in the Grand Salon. His Paris studies in anatomy led to his later book Studies in the Art Anatomy of Animals (1896), which, according to editor John Samson, “could stand today as a textbook for veterinarian medicine [because the] illustrations are marvels of study and work.”

On his return to the United States in 1892, Seton achieved his first literary success. Hired as a wolf killer in New Mexico, he learned to eliminate these predators, which, at the same time, he grew to admire. These experiences he turned into the first of his famous animal stories, “The King of the Currumpaw,” published in Scribner's Magazine (1894). The plot of this tale served as a pattern for numerous others in which some animal successfully copes with a series of perils, only to die courageously in the end. Seton felt this sequence was typical in nature.

After further travel in the West, Seton undertook more art study in Paris. In 1896 he married Grace Gallatin (Grace Gallatin Thompson Seton), the daughter of California financier Albert Gallatin. His wife, an author and social leader, aided him in editing and designing his books. The couple had one daughter, Ann, who became the novelist Anya Seton. Almost from the beginning, the Setons' lives diverged, though they remained on cordial terms.

Detail from Library of Congress No. LC-USZ62-115320.

The next decade Seton spent exploring wild areas of North America, including the Yellowstone, Wind River, and Jackson Hole. In 1900 he took a trip to Norway, and in 1907, a 2,000-mile Canadian canoe trip that nearly reached the Arctic Circle. During this time, Seton had camped in most U.S. and Canadian wilderness areas and produced and illustrated some twenty books. The Arctic Prairies (1911), a lengthy account of Seton's seven-month north Canadian canoe trip, revealed, in addition to other things, his mixed response to the Indians of his day and their life styles. Early editions antagonized some biologists who resented Seton's failure to acknowledge the contribution of Edward A. Preble, his guide and a U.S. Biological Survey staff member, to the success of the trip.

By 1910, Seton was one of the country's leading nature writers and illustrators; his popularity as a public speaker brought him up to $12,000 annually. Wild Animals I Have Known (1898) was easily his most successful literary effort. A bestseller in its time, it has been continuously in print since its original publication. With this book, Seton invented a tradition of animal stories, which later attracted such writers as Jack London and earned him the friendship of President Theodore Roosevelt.

His literary friends included Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, together with John Burroughs, the outstanding nature essayist of the period.

Seton's reputation, however, was not invulnerable. In an article in the Atlantic (Mar. 1903), Burroughs made him a major target as one of the “Nature Fakirs,” who attributed powers of reason to animals and insisted that such characterizations were factual. Roosevelt and Chapman, realizing the value of Seton's work, advised Burroughs against further attacks. Burroughs; sequel article (July 1904) ranked Seton first among contemporary younger naturalists but warned that his stories required the reader to separate truth from fantasy. Roosevelt was among those who persuaded Seton to back up his stories with the publication of facts.

Seton set to work; Life Histories of Northern Animals (1909) dealt with sixty of the more common North American mammals. Critical response was highly favorable. The work received the Camp Fire Gold Medal. The next fifteen years were chiefly devoted to producing the massive Lives of Game Animals, a four-volume work published between 1925 and 1929, which won him the coveted John Burroughs (1926) and Daniel Giraud Elliott (1928) medals. By ably blending his field experiences with the writings of zoologists and other observers, Seton had created a work that was eminently readable, yet reflected the latest scientific thinking. His landmark insights into animal psychology and emphasis on life histories gave the work its standing as a classic.

As an artist Seton has never been recognized as being of first rank. Most of his mammal paintings were good, if academic, but he is considered to have been best at producing pen and ink field sketches. His forte was depicting quadrupeds, but his quick sketches of birds were also evocative. Although Seton never mastered the look of flight, he devised the field identification system later developed in Roger Tory Peterson's Field Guides. As an illustrator, Seton set the standard for later work done by Louis Agassiz Fuertes and others. His unique combination of writing and illustration made him an exceptionally effective publicist for nature.

In 1910 Seton played an important role in the formation of the Boy Scouts of America, writing the original handbook, The American Boy Scout: The Official Handbook of Woodcraft for the Boy Scouts of America (1910), and serving as chief scout until 1915. Seton, however, wanted scouting to emphasize campcraft and Indian ways instead of uniforms, discipline, and slogans; he later broke with other leaders of the movement, notably William Hornaday, to give greater attention to his own organization, the Woodcraft Indians, which he had founded in 1902 and which idealized Indian life and lore.

In 1930 Seton became a U.S. citizen and left the East to settle in New Mexico. Purchasing 2,500 acres near Santa Fe, he built “Seton Castle,” a structure of stone and adobe whose thirty rooms contained most of his 8,000 paintings and drawings, 13,000 books, and 3,000 mammal and bird skins. Here he established his College of Indian Wisdom. In 1935, four days after divorcing his first wife, Seton married Julia M. Buttree, a student of Indian lore who was almost thirty years his junior. The couple later adopted a daughter. He died at his home near Santa Fe and was cremated in Albuquerque. His home is maintained as a museum and center for the study of Indian life.

Most Seton material, principally illustrations and papers, is in the Ernest Thompson Seton Memorial Museum at the Philmont Boy Scout Reservation, Cimarron, N.M. There and at Seton Castle in Santa Fe, N.M., owned by his adopted daughter, Beulah Seton Barbour, are 2,000 of Seton's best paintings, drawings, and etchings. Thirty-eight volumes of his journals, sold at auction by his wife's direction in 1965, are held in the Rare Book Room of the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. Seton's autobiography, Trail of an Artist-Naturalist: The Autobiography of Ernest Thompson Seton (1940), was reprinted in 1978. Useful compilations of Seton's writings include The Best of Ernest Thompson Seton, ed. W. Kay Robinson (1949); Ernest Thompson Seton's America, ed. Farida A. Wiley (1954); By a Thousand Fires: Nature Notes and Extracts from the Life and Unpublished Journals of Ernest Thompson Seton, ed. Julia M. Seton (1967); and The Worlds of Ernest Thompson Seton, ed. John G. Samson (1976). Of his roughly fifty books, several are anthologies of articles previously published in such periodicals as Scribner's, the Century, Ladies' Home Journal, Country Life in America, St. Nicholas, American Magazine, Forest and Stream, Bird-Lore, Boy's Life, American Boy, and Recreation; these collected tales include Wild Animal Play for Children (1900), Animal Heroes (1905), Natural History of the Ten Commandments (1907), Wild Animals at Home (1913), Wild Animal Ways (1916), Woodland Tales (1921), and Cute Coyote and Other Animal Stories (1930). His outdoor guides included American Woodcraft for Boys (1902), The Birchbark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians (various editions, 1906-1931), The Forester's Manual (1911), The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore (1912), The Woodcraft Manual for Girls (1916), The Woodcraft Manual for Boys (1917), and Sign Talk (1918). A number of scientific articles appeared in the Auk and the Journal of Mammalogy, among others. Biographical studies include John Henry Wadland, Ernest Thompson Seton: Man in Nature and the Progressive Era, 1880-1915 (1976) which provides the most comprehensive listing of Seton's books and articles; Betty Keller, Black Wolf: The Life of Ernest Thompson Seton (1984); and H. Allen Anderson, The Chief: Ernest Thompson Seton and the Changing West (1986). Ralph H. Lutts, The Nature Fakers: Wildlife, Science and Sentiment (1990), places Seton in the context of the Nature Faker controversy of the early twentieth century. An obituary is in the New York Times, 24 Oct. 1946.

Keir B. Sterling

Keir B. Sterling. "Seton, Ernest Thompson";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-01495.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Aug 14 2006 23:07:02 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Reproduced with permission granted for this verbatim copy of an ANB Biography of the Day provided that the copyright statement is preserved on all copies.

- Science Quotes by Ernest Thompson Seton.

- 14 Aug - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Seton's birth.

- Silverspot, The Story of a Crow - from Wild Animals I Have Known (1898) by Ernest Thompson Seton.

- Ernest Thompson Seton: The Life and Legacy of an Artist and Conservationist, by David Witt. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Ernest Thompson Seton.