(source)

(source)

|

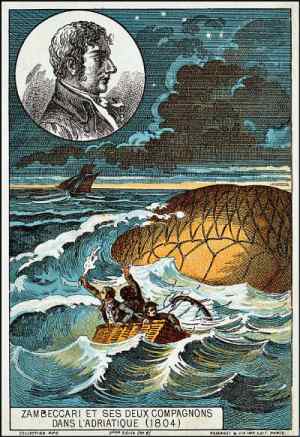

Count Francesco Zambeccari

(1752 - 22 Sep 1812)

Italian balloonist and navy officer who published a five-volume work on ballooning and aeronatics (1803).

|

Von Zeppelin’s Forgotten Predecessor.

Zambeccari’s Wonderful Airship in 1803.

from Scientific American (1908)

[p.215] The name of the man who apparently first succeeded in steering an airship has long been forgotten by the generality of mankind and is preserved only in the French “Biographie Universelle,” in a little-known book of travels by Kotzebue, and perhaps in a few technical works. It is worthy of remark that this pioneer in aviation was neither a physicist nor a mechanician, but a naval officer.

Count Francisco Zambeccari was born in Bologna in 1756. After completing his education, which was a very good one, he entered the Russian navy. In 1787 he was captured by the Turks and held prisoner in Constantinople for three years, but finally obtained his liberty through the intercession of the Spanish ambassador. Thenceforth he devoted his entire attention to the problem of directing the course of a balloon. His predecessors, with the exception of Leonardo da Vinci, had constructed fantastic devices which had no basis in experiment or observation of nature. Zambeccari, on the contrary, investigated the peculiarities of atmospheric currents and was the first to conceive the idea of controlling the course of a balloon by rising or sinking from an unfavorable to a favorable current in which oars could be used to advantage. In order to carry out this idea it was necessary to construct a balloon which could be raised and lowered at will, and this Zambeccari succeeded in accomplishing. The inventor was killed in 1812, by the wreck and explosion of his airship, in which he had ascended during a storm.

Kotzebue had found him in bed, suffering from the effects of an earlier accident. Kotzebue says: “I learned the details of his ever-memorable flight through the air and saw the lamp which enabled him to rise and fall at will. It is undeniable that a balloon in equilibrium with the surrounding air can be moved horizontally by an exceedingly small force. This force in Zambeccari’s balloon is furnished by small attached vanes. I was assured by several eye witnesses that he undertook to “fly to and return from two towers, situated in different directions from the starting point, and accomplished both tasks with a very small expenditure of force.”

One of Zambeccari’s memorable flights was made in 1803. He was enabled to construct his airship by the interest of the celebrated mathematicians, Saladini and Canterzani, who induced the government of Bologna to grant him a subsidy of about $1200. The flight had been announced to take place on September 4, but bad weather and small defects in the balloon had necessitated a postponement until October 5. On that day the weather was again unfavorable, but Zambeccari was driven by the jeers of the spectators, as he said afterward, to attempt the flight. The balloon was carried out to sea, where it and its half-drowned occupants were secured by fishermen and taken to Pola.

Although this attempt had ended in so disastrous a failure, the professors, Saladini, Canterzani, and Avanzini, to whom the matter had been referred by the government, brought in a favorable report, which was printed November 9, 1804. This report is not accessible to the present writer, but Kotzebue, who appears to be well informed, gives substantially the following account of it.

The referees lay down the following law: “If a partly-filled balloon is in equilibrium with the air at any point, for example, near the ground, it will remain in equilibrium when it is transported to any other point of the atmosphere, so long as the gas is allowed to expand or contract.” In other words, the volume of the partly-filled balloon varies inversely as the density of the surrounding air. The referees acknowledge that this law was discovered and demonstrated by Zambeccari. Then they speak of his lamp, of the absence of danger in the use of fire and inflammable gas in the same apparatus, and of the manner in which Zambeccari, with the aid of the lamp, was able to ascend, descend or remain stationary at will without using a single valve, losing any inflammable gas or throwing out any ballast. Then they describe the rudders, by means of which the inventor had previously propelled a light car suspended from the roof of a church, in the presence of many persons. They assert that Zambeccari, in his last flight, hovered a long time over Bologna, ascended and descended at will, and described an arc round the city from south to west, solely by means of his flame and without throwing out ballast, for they had observed him carefully with telescopes. In conclusion they state that Zambeccari has succeeded in proving his theory by actual flight and that the misfortune that has twice overtaken him can detract nothing from his fame or the value of his invention.

The balloon used by Zambeccari was of the type known as a rozière, consisting of a montgolfière, or fire balloon, in combination with a gas bag, the latter giving a constant buoyancy, while ascent and descent could be accomplished by regulating the flame of the hot air balloon, without expending gas or ballast. Just what the “oars” were with which he drove his craft is not clear.—Umschau.

- 22 Sep - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Zambeccari's death.