(source)

(source)

|

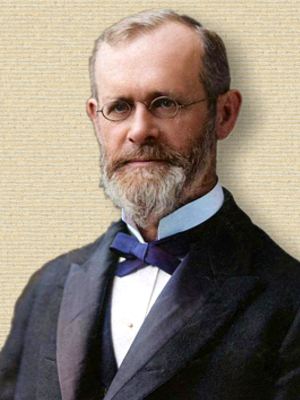

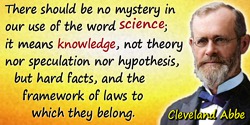

Cleveland Abbe

(3 Dec 1838 - 28 Oct 1916)

American meteorologist, inventor and astronomer , who as America’s first professional meteorologist is regarded as the “father of the U.S. Weather Bureau.”

|

How the United States

Weather Bureau Started

by Cleveland Abbe, its Founder and Organizer

from Scientific American (20 May 1916)

My boyhood life in New York city had impressed me with the popular ignorance and also with the great need of something better than local lore and weather proverbs. The popular articles in the New York daily papers by Merriam, Espy, Joseph Henry and others—notably Redfield and Loomis—had by 1857 convinced me that men could and must overcome our ignorance of the destructive winds and rains. It was in the summer of 1857 (1858?) that I read the beginning of the classic article by William Ferrel in the “Mathematical Monthly.” I realized that he had overcome many of the hidden difficulties of the theories of storms and winds. From that day he was my guide and authority. During 1859-1864, in the practice and study of astronomy with Bruenow at Ann Arbor and Gould at Cambridge, Mass., I was impressed with the unsatisfactory state of our knowledge of atmospheric refraction. Two years later my experience at Poulkova, Russia, and at our Naval Observatory, Washington, seemed to justify my conclusion that astronomers who would improve their meridional measurements must investigate their local atmospheric conditions more thoroughly, and to this end must have numerous surrounding meteorological observations. In my inaugural address at Cincinnati on May 1, 1868, I stated that with a proper system of weather reports much could be done for the welfare of man, and astronomy also could be benefited.

This suggestion was taken up by Mr. John Gano, president of the local Chamber of Commerce; a committee met me, approved my plans and promised the expenses of the first trial. I had the total solar eclipse of August 7, 1869, on my hands, but immediately began to arrange for forty voluntary meteorological correspondents. On my return from the eclipse at Sioux Falls city I stopped at Chicago and formally invited the Chicago Board of Trade to join in extending the Cincinnati system to the Great Lakes, but this invitation was declined by the Chicago Board of Trade. An editorial in a Chicago evening paper of Monday, August 16, 1869, stated the scientific basis of our observatory works.

I returned at once to Cincinnati, issued the first number of the Cincinnati Weather Bulletin promptly, as promised, on September 1, 1869; it contained only a few observations telegraphed from distant observers and announced “probabilities” for the next day. This bulletin, in my own handwriting, was posted prominently in the hall of the Chamber, but unfortunately I had misspelled Tuesday, and I soon found below my Probabilities the following humorous line by Mr. Davis, the well-known packer, “A bad spell of weather for ‘Old Probs.’” This established my future very popular name of “Old Probs.”

My forecasts were treated very kindly by all. I had anticipated a slow increase in accuracy; I ventured to write my father in New York city, “I have started that which the country will not willingly let die.” I wrote a short note to the New York Times (or Tribune), telling them how useful we could be to their shipping. On September 3, 1869, I even ventured to offer a daily telegram by the French cable to Le Verrier as founder of the “Bulletin Hebdomadaire de l’Association Scientifique,” and who could fully sympathize with my hopes and plans. He realized the breakers ahead of me better than I. My daily telegram from Milwaukee came from the well-known Smithsonian observer and author, Prof. Increase Allen Lapham. He had known and appreciated the works of Espy, Redfield, Loomis and others, and although he had become absorbed in other studies, he urged the local Milwaukee society to do something for Lake Michigan. His friends were just about to go to the Richmond meeting of the National Board of Trade; there they met William Hopper and John A. Gano. These merchants of Cincinnati found that they had the same idea as H, E. Paine of Milwaukee, i.e., that the Federal Government should develop the Cincinnati enterprise and make it useful to the whole country. The National Board of Trade indorsed this idea, Prof. Lapham of Milwaukee drew up some statistics of storms and destructions on the Lakes, the Hon. Halbert E. Paine prepared a bill; we each put our shoulders to the wheel, and behold, on February 9, 1870, the Secretary of War was authorized to carry out this new duty. I had spent a year in finding stations, voluntary observers and telegraph facilities; every old classmate or friend of progressive meteorology had helped the new idea.

The work had now, as I supposed, passed out of my hands, but there was in reality much more for me to do. A letter from the Chief Signal Officer, U.S.A., General Albert J. Myer, asked for all possible coöperation. The officials of the Western Union Telegraph Co. offered the Observatory the same free daily weather reports that they had for twenty years been giving to the Smithsonian Institution and the daily press, so I continued temporarily to make and publish the Cincinnati Bulletin, but in a much simpler form and without forecasts. This continued until May 10, 1870, when I was married, and the preparation of the midnight bulletin passed over to the officials of the local telegraph office. It was continued in this shape until November, 1870, when the tri-daily bulletins of the Army Signal Service began. With the help of Mr. Williams, who was in charge of the Western Union office, I printed in October, 1869, a code of cipher, and should have used this code for economy had not the law of February 9, 1870, rendered further reports by our stations unnecessary. This code was subsequently greatly improved by the Weather Bureau men, and particularly by Gen. A. W. Greely, and it is still in use.

The manifold duplicate copies and the printed copies of the daily Cincinnati Observatory Bulletin were distributed until the Chamber of Commerce no longer needed to support it, then Mr. Williams devised a simple form of manifold map that was a great improvement on my original tabular form of daily reports. This map was soon adopted by the Signal Service, but was itself displaced in turn by the present handsome daily lithographed chart. Without the help of Armstrong and Williams and the new manifold method we could not have promptly responded to the needs of our friends. By November, 1870, I had gone to New York and prepared to go as astronomer on one of the Panama Canal surveys, but I gave this up and should have returned soon to Cincinnati had I not, in December, received a letter from General Myer stating that he wished to see me. My work with him in the Weather Bureau of the Army Signal Service began January 3, 1871. After a month’s practice it was decided that my forecast would evidently more than fill the popular expectations, and tri-daily publications began at once. The term “probabilities” then became official, as it had begun in October, 1869, and in those days it was appropriate; but we have long since substituted the word “forecast.”

The subsequent development of the service under Generals Myer, Hazen, Greely, and Professors Harrington, Moore and Marvin, may be gathered from their special or annual reports. The service has been greatly favored by the hearty coöperation of many men of knowledge, skill and enthusiasm.

Franz Brünnow

- Science Quotes by Cleveland Abbe.

- 3 Dec - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Abbe's birth.