(source)

(source)

|

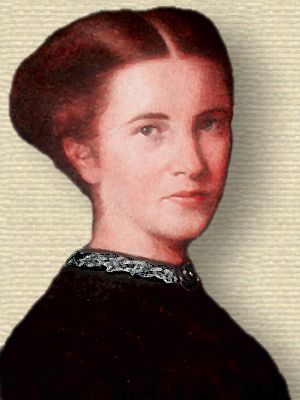

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

(9 Jun 1836 - 17 Dec 1917)

English physician and activist who was the first woman in Britain licensed as a medical practitioner. She founded the St. Mary’s Dispensary for Women in London

|

HOW CAN CHILDREN IN A CITY BE KEPT HEALTHY?

BY ELIZABETH GARRETT ANDERSON, M. D.,

London, England.

from The Sanitary Care and Treatment of Children and Their Diseases (1881)

[p.1] It is plain that this question is a very much more complex one than any which concerns itself only with the study of the conditions which are ideally best for the production of health in children or in adults. Town life is not what suits children, and the problem of how far and by what methods we can get them to submit to unnatural conditions without being seriously injured is a much more intricate one than that which seeks only to determine what it is which would be absolutely best suited to them.

But Arcadia is a long way off, behind, or possibly in front of us. We have to deal with life as it is, and this includes many thousands of children dwelling in a city, with all its dangers and difficulties. It is of no use to lament this; we must accept the fact and see how far the evils of such a life can be corrected or avoided. The first step in the inquiry is taken by asking what it is that children most want in order to be in sound health. We know that the essentials are fresh air, suitable and abundant food, to have come of a healthy stock, to be guarded from accidental contact with sources of contagion, to be protected from all the influences which would interfere with the normal development and stability of the nervous system, — such as undue and too early toil, anxiety, want of adequate rest and recreation, unsuitable or excessive excitement, [p.2] — and in early infancy, at any rate, to be the objects of a minute and all-watchful care. We shall have occasion to study these essentials at length further on; all that is necessary now is to notice them in a passing way, having the conditions of town-bred children in our minds as we do so. It may be well here to suggest the thought that these essentials, though rightly so-called, are not all and everywhere of equal value. Pure air, for instance, is of such paramount importance that where it can be had children live, and thrive upon poor food, in squalor and dirt, and with the minimum of care; whereas without pure air, or in air distinctly impure, very few children can thrive, however well they are supplied with all the other essentials of health; and no doubt the superlative importance of fresh air in children’s hygiene partly works by the influence its presence has in diminishing the importance of food, cleanliness, and care. With it children can bear neglect and the complete absence of minute care in a way which would be impossible to those breathing an air even but moderately impure. They can do without wisdom in their mothers with a comparative immunity from harm which no town-bred child can imitate. If the commonly received essentials of health were classified according to their relative importance, fresh and pure air would, for children at any rate, take the first place, and cleanliness the last. Even in towns, where the skin seems to be more neglected than in the country, or where perhaps the dirt is more enamelling in character, and therefore more injurious, it is surprising how little harm seems to result from dirt, and how little mere skin cleanliness seems to benefit the health. In London we should be disposed to say that as a rule, among the lowest classes, the dirty are more vigorous than the clean, and to explain it by noticing that the dirtiest are those whose trades are carried on out-of-doors. The moral influence of dirt is probably much more serious and damaging than its physical effect.

When we begin to consider in detail those conditions which we have called hygienic essentials, the difficulties which beset town-bred children become very evident. Let us take pure [p.3] air first in the list, as it indeed well deserves to be taken. By the term “pure air” we mean an air containing no appreciable admixture of the exhalations of men or animals, free from malaria and sewer gases, from the products of combustion, especially when this is imperfect; free from the products of decomposition of either animal or vegetable matter, from the organic germs which result from a rank vegetation; an air, finally, which can move, and which is not shut off from the influence of the sun. Such conditions are best fulfilled in sea or mountain air, but by no means invariably even in these.

For children, sea air has qualities which apparently none other can rival; but whether these are the result of the small amount of contained iodine, or of a higher degree of purity than that of ordinarily good mountain air, or of its more powerfully stimulating effect upon the functions of nutrition and assimilation, is still undetermined. It is at once apparent that to children in towns pure air, as now described, is an impossible luxury. Rich and poor alike must do without it, and . the only practical points worth prolonged consideration are, how can the air be made as little impure as is possible under the conditions, and how can the children get as much as possible of this only moderately impure air? In dealing with the first of these two points, let us think of the air first as it is in the town, and then as it is in the children’s homes. Outside the houses the air will of course be greatly influenced by the position of the town, its elevation, its exposure, the presence or absence of marshes or other sources of malaria, the greater or less closeness of the houses, the width and aspect of the streets; whether these are for the most part properly laid out and open to a through current of air or not, the system of drainage adopted, the amount of fall provided in the main drains, the abundance of the water supply for flushing the sewers, the total annual rainfall and its distribution through the various seasons, the state of the streets as to cleanliness, that is, the rate of removal of refuse, of dust, etc.; the presence or absence of noxious trades, more especially manufactories which produce poisonous vapors and dense smoke, the [p.4] sanitary condition of slaughter-houses, mews, stables, and markets, and the presence or absence of grave-yards. All these and similar influences must greatly affect the degree of impurity of town air. Assuming that a town is efficiently drained and cleansed, and free from malarial or miasmatic influences, the point of chief importance of all those just enumerated is the density of the population. Where the streets are narrow, the houses high and crowded, and the open spaces few, there must the air be most laden with impurities, there must it be the farthest removed from that aseptic condition which young life especially needs.

Passing from the air of the street to that in the children’s homes, we see that at the best it cannot be better than the outside air, and is almost certain to be very much worse. It must contain all the impurities of the outer air, and it can scarcely avoid having a good many of its own. In the first place, there are but few houses which are not liable to the invasions of sewer gas, either by direct communication with the drains, by the absence of adequate sewer ventilation, by the leakage of pipes, by drains being riddled with rat-holes, or having an insufficient fall, or getting their outlets blocked. Even in good houses, where the occupier would not hesitate a moment to spend any necessary sum to insure the absence of these defects, if suspected, they are frequently present for months before they are discovered, and are as often the source of illness, or of debility and languor. It is easy to understand that they must be still more often present when the house is sub-let to many families of tenants, and when the owner desires to spend as little upon it as is possible. The second great source of the added impurity of house air over and above the impurity outside, is found in the crowding which prevails in the poorer quarters of every large city. Adequate ventilation is simply impossible wherever a whole family occupies one small room. Even in the summer time, with open windows, the air does not move with sufficient rapidity; it becomes gradually saturated with exhalations; and at night and in the winter it is still worse. The immense [p.5] importance of this point, especially to children, is at once seen when we think of the number of hours passed in sleep. Well-cared-for children are glad to sleep eleven or twelve hours out of the twenty-four till they are seven years old, unless they are exceptionally vigorous; and though poor children do not as a rule get a chance of such long nights as this, they are probably in bed nine or ten hours daily. Nothing can make up to them for the evil of breathing fetid and impure air uninterruptedly for so large a part of each day. In the day-time the injurious influence of crowding appears to be most felt by the more respectable sections of the town poor. Especially is this true of the children. It is very striking in London to notice how much more robust the children of the careless class of mothers are when past early infancy than those of the careful. Roaming the streets all day, playing marbles, dancing to the hurdy-gurdies, or watching Punch and Judy, may be bad training for the morals, but it suits the children’s health much better than careful guarding and keeping at home. Imperfect as the air of the streets is, it is better than that of the houses; and where, as in London, there is no malaria to fear and guard against, the best remedy for the indifferent quality of town air is to take a great deal of it in quantity. Nothing can exceed the value of open spaces in cities to all classes, but more particularly to young children, and to the poor generally. In London, though we are better off for parks and large open areas than they are in most of the cities in Europe, we yet sadly need the multiplication of small and handy spaces within two or three minutes’ run of the children’s homes. Probably no single act would confer half so much benefit upon the London poor as buying up the private rights to the squares in the poorer and more crowded quarters, and throwing them open to the public. But even where everything possible is done to improve the purity of city air, and to increase the quantity available for respiration, it cannot either in quality or quantity compare with pure country air, and children cannot be induced to ignore its inferiority. Even to the classes inhabiting [p.6] large and airy houses in the best quarters of a town, it is almost a sine qua non, if the children are to grow up strong and healthy, to take them into the country once a year. How much more necessary must such a change be to children living in narrow, closely-packed streets and courts, in houses where every room is as full as it can be packed with human beings!

It must moreover not be forgotten, that the imperative necessity for occasional escape from city air which exists for all children is indefinitely more urgent wherever the average temperature of the three summer months amounts to 70° F., or above it. In this case it is no longer a question of keeping children healthy, but of keeping them from dying. In London, the moment the average daily temperature exceeds 70° F., children die in numbers every week from diseases which seem to depend intimately upon the combination of a moderately high temperature and city air.

How it is, exactly, that summer diarrhoea so frequently accompanies a temperature not in itself trying to most healthy adults, we do not yet know. Its precise causation is still, no doubt, a matter of dispute; it is impossible to explain it simply by the presence of a certain degree of summer temperature. Leicester, for instance, is not hotter than many other towns in England in July and August, though its diarrhoea mortality is often greatly in excess of theirs. Everything points to the conclusion that the aetiology of infantile diarrhoea is complex, and that high temperature is but one of its important factors, while impurity of air is another. Probably the two combined induce subtle changes in milk and other staples of children’s food. Certainly, no one can observe the swiftness and certainty with which, among hand-fed and ill-tended children, this class of disease follows a rise of temperature, without suspecting it to be due to the direct introduction into their bodies of actively developing germs which the high temperature has supplied with one of their necessary conditions of activity. The fact that children who still depend mainly upon cows’ milk are the chief sufferers seems to [p.7] point to the milk as the probable vehicle by which the infective particles obtain an entry into the child’s digestive tract. Whether this hypothesis be true or not, it is certain that infantile summer diarrhoea, though not unknown in the country, is indefinitely less of a danger there to well-fed and well-cared-for children than it is in cities, and that the principal weapon with which the ravages of the disease can be combated is moving children of the most susceptible age, that is from eight months to two and a half or three years, into the country during the dangerous months of each year. Among the classes where this is as a rule impossible, and where no extraordinary caution as to the quality and storage of the milk supply is likely to be shown, summer diarrhoea will probably continue to be an ever-present danger if not altogether the scourge it is at present, so that to the question,” How could it be prevented?” we are obliged to answer that, so far as we know now, it cannot absolutely be prevented, and that the utmost that sanitary science can do at present is to show communities where the danger lies, and individuals the only known protective agency. A minute and laborious study of the influence of heat on milk and other common articles of nursery food would certainly be worth making. Now that fresh meat can be carried across the tropics and up the Red Sea from Australia to England, absolutely free from putrefactive change, and at a very moderate cost, it ought not to be impossible to supply young children in cities with their necessary food quite unaffected by an outside temperature of 72° F. or upwards. The subject is one which might well engage the attention of men of practical science in those towns where the average summer heat is recognized as one of the most serious enemies to infant life. In this country, though we are almost every year reminded for a very short time of the dangers of heat, a temperature of 72° F. or upwards is seldom maintained for more than a few days at a time, and often for not more than two or three weeks in all throughout the year. Diarrhoea is therefore not the grave and ever-present danger in our minds that it is in those of people living in semi-tropical towns.

[p.8] On the other hand, the damp and cold of England and the choking oppressive fogs of London bring a train of evils of their own in the direction of catarrhs, bronchitis, and asthma, evils which, important in themselves, are aggravated by the length of time to which we are exposed to them. Happily, however, they admit of being considerably diminished by careful management, and, in the comfortable classes at any rale, children in London can be kept well through a winter lasting five or six months very much more easily than they can be through even two months of high summer temperature. The immediate evils resulting from the cold and damp and fog of a London winter, though by no means unfelt by children, press with their greatest heaviness on the old and infirm, a fact which was exemplified during the past winter, when in one week in February, 1880, characterized by severe cold and peculiarly irritating fogs, the death-rate in London amounted at once from twenty-seven to forty-eight per one thousand, mainly from the greatly increased number of deaths among old people. A general diffusion of sanitary knowledge, increased temperance on the part of the parents, and a heightened standard of comfort, may be expected to diminish very appreciably that proportion of the infant mortality which is directly due to the conditions of the London winters. As a rule, indeed, children who are well fed, well clothed, and well housed, keep particularly well in London during the winter. What the poor chiefly want to learn with regard to the winter management of their children is the immense value of warm clothing, and if the mothers had more money to spend they would soon learn this. The children often wear too little flannel because the father drinks too much beer.

Next in importance to fresh air and the influence of temperature comes the question of food. Children urgently need both a suitable and abundant food supply, and we have to ask how their chance of getting this is affected by city life as compared with life in the country. If we are careful to contrast the condition of parallel classes, and to avoid the [p.8] mistake of supposing that every one in the country has a cow and a farm-yard of his own, we shall probably come to the conclusion that only a small part of the extra difficulty of keeping town children in health can fairly be attributed to the inferiority of their food supply. In many cases suitable food for children is even more difficult to get in the country than in large towns. Milk, for instance, is to the poor an impossible luxury in many country districts in England, and eggs and butter are scarcely less so. In London these are all within every one’s reach, and though perhaps of but indifferent quality, they are of great importance in the children’s dietary. Variety of animal food, of vegetables and fruit, is also much more within the reach of the poor in towns than in the country. What the country gives in this direction to the children of the poor which the town does not give them is the appetite to eat abundantly, and vigorous powers of digestion and assimilation. Nutrition advances more rapidly in the country, not because to the poorest classes the food supply is better, but because the power to use it is larger and less fastidious. So that even from the stand-point of nutrition we come back to the far-reaching influence of fresh air. If we inquire how sanitary science in its application to town life could favorably affect the food supplies of children, it is easy to see that, though they do not as a rule die from any impossibility of getting fairly wholesome food, there are many ways in which it could be improved. In London the adulteration of milk, butter, bread, and everything else which can be adulterated, is a grievous injury both to children and to adults. Children, however, suffer more seriously from their parents’ want of knowledge and judgment in the choice of food than from its quality, and more especially from the indolence which leads to feeding infants on food only suited to adults. Much has been done in this country to awaken the attention of mothers to the evils of such indolence, especially by very simple popular lectures at mothers’ meetings, and to the elder children in schools; and it may be anticipated that, in time, agencies of this kind will do a good deal towards diminishing the evil. In [p.10] a large city money could with great advantage be spent in supplying sanitary lecturers specially trained to deal with poor mothers, and to teach them, both by theory and practice, how to adapt the dietary of young children to their special needs, and how to improve the dietary of the adults of their family. The object would probably best be attained by employing people of the class of Bible-women, or district or parish nurses, and giving them a simple and practical training specially addressed to this subject. No machinery is likely to be of much value which cannot be carried into the very homes where the teaching is wanted, and only women can so carry it.

The first eighteen or twenty months of life is the time when suitability of food is of greatest importance, and even of this time the earliest months are of far more moment than the later ones. Nothing can make up to an infant for the want of its natural food during the first year of life, and wherever the mothers are to any considerable extent engaged in manufactories, or in work which separates them from their infants, the effect is sure, in a large majority of the cases, to appear in the debility or death of the children. It is no doubt true that many children of a higher social class are successfully reared upon artificial food, but every mother or nurse who has succeeded in doing this knows the amount of minute and incessant care, it requires — care of a kind, indeed, which it is unreasonable to expect from mothers who have the entire work of a household to perform. Even where this vigilant and skilled care is given, and where in addition the infant is helped by every hygienic resource, the attempt to do without its natural food often results in failure. Some advance, however, has been made in recent years in the study of substitutes for the mother’s milk, and there seems no good reason why a still greater measure of success may not ultimately be reached.

One main element in the difficulty of artificial feeding no doubt lies in the great liability to change, characteristic of human, as well as of other milk. Probably organic fluids exposed to air at ordinary temperatures are always changing [p.11] more or less rapidly, and, apart from its easily recognized chemical difference, much of the peculiar virtue of human milk as food for infants may be in its freshness, in its perfect freedom from infective particles, nay, even in its nascent character. Mothers at any rate agree in thinking that infants neither like nor digest so well milk which has remained an hour or more in the breasts as they do that which is, as it were, manufactured expressly for them the moment it is wanted. It is difficult to anticipate that organic chemistry will ever so completely yield up its secrets as to enable us to understand how this subtle change is effected, or to produce a food at all comparable to that provided by nature. Probably to the end of time the real thing will be much better than any imitation, and some children will always refuse to thrive, or even to live, upon anything but their dietetic birthright. For those, however, who cannot avoid the risk involved in artificial feeding, and also for young infants when partially or wholly weaned, carefully prepared diet rules are, in careful hands, of great practical value. They need to be plain, minute, and dogmatic. Any attempt at physiological or chemical explanation is sure to be misunderstood, and the rule itself is more likely to be remembered if presented in a dogmatic form. The rules should state the degree of dilution cow’s milk requires at each age, how to prevent the formation of heavy curds in the process of its digestion, when to add an alkali, its form and quantity, when to begin the addition of farinaceous and animal food, and which of such kinds of food is best for children of each age. These are points so familiar to medical authorities that it would be superfluous to insert such rules in this paper. They can be found at once in the writings of Dr. Eustace Smith, Dr. J. Lewis Smith, Dr. West, and many others.

A further important part of the question of the food supply is that which relates to the drinking water. Young children should no doubt not be large water drinkers. Milk is their natural and proper drink till they are almost out of childhood. But to poor people milk is, as a rule, too costly to be [p.12] used in this liberal fashion, and the drinking water becomes to them as important for their children as it is or ought to be for themselves. The first thing that strikes one in thinking about the drinking water in connection with the special difficulties of city life is, that here we touch a point upon which town-bred children ought to have an advantage over their country cousins. And even with the many shortcomings (some of them scandalous ones) of our London system, it is probably true that London water is, as a rule, a less dangerous drink than that at the service of the English agricultural population. Whether this is so or not, it cannot be doubted that a community is in a far better position for getting wholesome water than single scattered families of poor and ignorant people ever can be, and that it is a grave blot upon their civic organization if they have not succeeded in getting it. A laborer’s country cottage must have its water supply close at hand, and it must be the cheapest possible; therefore it is a surface spring, and close to all the obvious sources of impurity round the house. As a rule, in England, the well and the cesspool, or the pig-sty, are within a few yards or feet of each other. In large towns there can be no real difficulty in carrying water of almost absolute purity to every house; it is simply a question of expense. In London, the system breaks down mainly on the point of the storage of the water in the houses. In houses for the richer people there are cisterns, often dirty, and often in direct connection with the drains of the house. Many of the houses for the poor have no cisterns, but only water-casks or butts, often not covered, and rarely if ever cleansed. Even if the water so stored is not very poisonous, it is most unattractive. It is scarcely possible under these circumstances to urge water drinking with much zeal. Bearing in mind all the temptations to intemperance which surround the toiling inhabitants of the poorer parts of our crowded cities, the sense of exhaustion which results from indoor labor, from the absence of pure air and bright light, it is impossible to regret too deeply the way in which, even from childhood, the poor are forced into drinking stimulants by the [p.13] want of wholesome and pleasant water. This, however, is a fault not inherent in city life, but one which results only from indolence, ignorance, and supineness, and will, it may be hoped, in time disappear. It is at any rate certain that a town-bred child ought to be better provided with pure water than poor country children are likely to be, and that the absence of wholesome water in a city is a misfortune which need not and ought not to be present, and one to which we should not allow ourselves to become reconciled.

The third essential condition of health in children is that they should have come of a healthy stock. This supplies, no doubt, one important factor in the comparative difficulty of rearing healthy children in cities. In many cases the influences of town-life before the children were born have deteriorated the health of their parents. In every crowded community intemperance, tuberculosis, and syphilis undermine the health of thousands of parents at a comparatively early age, and the children born of such parents cannot be healthy. Not, of course, that either vice or constitutional disease is rare in the country; probably morals are much the same in a given grade of education and intelligence everywhere, but the influences of town life tend to increase the temptations to vice and to aggravate its physical results. In some cases moreover, country life, with its fresh air and the stimulus this affords to all the nutritive functions, may just supply the child of moderately unhealthy parents with what it needs to enable it to revert to a higher standard of health. For it is necessary to bear in mind that powerful as are the laws of heredity, like to their parents as children are and must always be, there is yet in human beings under favorable circumstances an uncontrollable set towards health and against the perpetuation of disease. If it were not so, if the force of heredity were strong enough to be able to brand the children through many generations with the results of the intemperance, the vice, and the recklessness of their forefathers, who among us would be sane, or wholesome, or healthy? Probably no one could show a clean bill of health, with regard [p.14] even to the worst diseases, for even so short a time back as ten or twelve generations, and what are these in the life of the race? There is, for instance, no disease more truly constitutional in character, and therefore more ready to pass from parents to children than gout, and yet we constantly see people who though coming of a gouty stock, by leading strictly temperate and active lives have almost completely freed themselves from their hereditary enemy, and who do not transmit it to their children so long as they also lead healthy lives. So that but a few generations, two, or three, or four, may suffice to do away with this otherwise most powerful hereditary taint. But no doubt it is true that the regenerating process, by which the race casts off gradually its acquired imperfections and tends to revert to the normal condition of health, requires both time and favoring conditions. Children are too close to their parents in point of time not to be very like them, flaws and all, and unless their inherited flaws can be met and counteracted by wholesome influences, the process of regeneration must be delayed, or even in the worse case, as is so often exemplified in the gradual intensification of nervous diseases, a downward course may be taken, and the constitutional type, instead of improving, will progressively degenerate. City life as lived by poor children is certainly not that which would enable them even to begin to throw off inherited imperfection; and practically we find, and probably always shall find, a vast amount of disease or imperfect health due to hereditary influences which no perfection of hygiene, so far as it can be applied to the town life of the poor, can tend greatly to diminish.

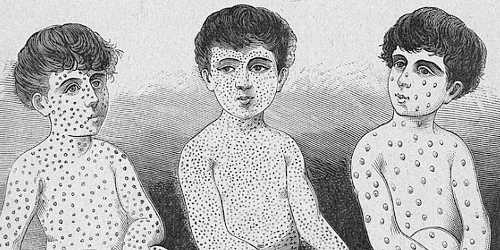

The next important element in the question of how to keep city children healthy is that which relates to the prevention of the spread of infectious or zymotic disease. Diseases of this class are gravely important, not only from the very large number of deaths they directly cause, but also by the chronic debility or disease which too often results from them. This is a part of our subject which would amply repay the careful consideration of all who desire to benefit the children of a [p.15] town, for it is one in which much good may be done, though the parents themselves are not in a position to do it. The chief hindrance, indeed, to the most important measures in this direction will be found in the ignorance and unenlightened affection of the parents. It is of course vain to talk of disinfection or of precautions against the spread of disease while children suffering from measles, scarlet fever, small-pox, or whooping-cough, remain in their crowded homes. The only measure worth discussing is that of removing and isolating them. If the hearty cooperation of the parents could be won, every child taken ill with any of these diseases in a crowded house ought at once to be removed to a special hospital, and adequate precautions there taken against communicating the infection. The art of disinfection is gradually becoming so much better understood by professional advisers than it was even a short time ago, that it is not now Utopian to believe that were the sufferer once in skilled hands and isolated, the spread of these diseases from each separate case might be completely checked, and that by repeatedly stamping out infectious disease in isolated cases epidemics might be prevented. Such a scheme as this supposes a separate hospital, or at least a completely separate block of wards for each of the important zymotic diseases, each having a separate staff of nurses, and, if possible, separate and resident medical attendants and separate administrators. It seems plain, from the history of the epidemics of the Middle Ages, silent traces of which still remain in the vast lazarettos of Milan and other continental towns, that diseases which were then not less serious scourges than scarlet fever is now, have been practically stamped out by a general improvement in the sanitary condition of towns once decimated by them, combined with a rigid process of isolation whenever the diseases in question appeared in the community. We have become alive, within the last few years, to the danger of infection being spread wholesale, as it were, in several ways hitherto unsuspected. Epidemics of scarlet fever have now in several well-investigated cases been proved with almost mathematical precision [p.16] to have been due to the milk supply having been contaminated with the scarlatinal poison. An instance of this, hitherto unrecorded, occurred in Scotland three or four years ago. A large boys’ school at Aberdeen had part of its milk supply from a particular farm near by. A girl old enough to be of use in the dairy fell ill, and was shortly pronounced to be suffering from scarlatina. With commendable honesty the farmer sent down to the school, as soon as the girl’s illness was recognized, to ask if the milk should still be sent. It was stopped, but the supply of the day before and of the -same morning had already been used, and within thirty-six hours eighteen persons in the school-house were ill with scarlet fever, as well as several other persons in neighboring houses who had had milk from the same farm.

A man walks covering his mouth with a handkerchief. In the background are several link-boys paid a farthing to light a path carrying flaming pitch torches. CC BY 4.0 Wellcome Collection. (source)

This case was further remarkable from the fact that, so far as could be ascertained, the girl at the farm was the first person who had been ill there, and if so, the contagion from her must have been very active, even in the earlier and acute stage of the disease. Possibly, as suggested in reference to summer diarrhoea, the germs upon which contagion depend may find a very suitable environment in milk, and therefore may develop in it with unusual rapidity. A curious and unexplained fact about the epidemics caused or conveyed by milk is that the type of scarlet fever so conveyed has hitherto appeared always to be mild in character. Further observation of similar cases may serve to show that this has been merely accidental, but it is a point worth noting for future observation to confirm or disprove. No one knows yet why some epidemics of scarlet fever are so immensely more dangerous than others, and anything which could help to a clearing up of this point might prove to be of enormous practical value. If we knew the conditions, whether individual or general, which lead to the occasional development of malignancy in the scarlatinal poison, those conditions could probably be influenced favorably and the malignancy prevented or diminished.

Whilst waiting for the time when the general good sense [p.17] of the community shall make it possible to isolate rigidly every case of infectious disease, it would be well that the sanitary lecturers employed among the poor in a town should be taught practically a few of the more efficient and available processes for disinfecting clothes and bedding, such as that which depends upon the liberation of a large quantity of chlorine gas. It cannot, however, be too clearly insisted upon that disinfection in any sense which implies safety to the community is an impossibility in crowded houses, and among poor people who cannot afford to destroy their clothes and other property. Only as the handmaid to isolation is disinfection of substantial value. An exception to this assertion might, however, perhaps be made where the disinfection can be applied assiduously and skilfully to the centre of contagion, that is to the sick person himself. Even in a disease so eminently contagious as scarlatina, cases have occurred in which, without attempting any isolation of the patient, no infection has been conveyed, the result having apparently been due to the frequent inunction of the invalid with carbolized oil. Among the poor, however, precautions of this class are sure to be very imperfectly carried out, and the real check to epidemics of zymotic disease must be sought in isolating every case as soon as possible after it has declared itself. Even apart from their crowded homes, the ordinary conditions of life to children of the poor lend themselves with unhappy facility to the spread of infectious disease. From early infancy large numbers of children are grouped together, in day and Sunday schools, in church and chapel, in playgrounds and in the streets. Poor children know, as a rule, no solitude. They are always in society, and usually in a very crowded society. Objections are occasionally urged against infant and other primary schools on the ground of their being centres of infection, and no doubt it is true that every school must occasionally be open to such an accusation. It appears, however, to be useless to grumble at the school before making an attempt to isolate the contagion in the home. So long as cases of scarlatina and other infectious disease are allowed [p.18] to remain in houses of which, perhaps, every room contains a family, it would be beginning at the wrong end to exercise any very zealous supervision over the schools.

In addition to the prevention of epidemic disease, an intelligent guardianship of the health of town-bred children ought to consider to what extent it can aid in the prevention of various other familiar forms of disease, such as tuberculosis, rickets, syphilis, and nervous disease in its many forms. The inevitable conditions of city life — crowding, intemperance, vice, poverty, and struggle — render it all but certain that these diseases will continue common in cities, and that philanthropic efforts will not, except indirectly, greatly diminish the number of children injured or destroyed by them. We know, for instance, that the most potent weapon against the development of tuberculosis is abundance of open-air exercise and of good food. But we know also that to hundreds of the dwellers in cities abundance of either of these is out of the question. They have to struggle on upon the minimum rather than the maximum allowance of fresh air and food, and tuberculosis results.

Rickets ought no doubt to be capable of being materially diminished wherever the general standard of intelligence and comfort is tolerably high among the working people of a city. It is a rare disease when mothers are themselves well fed, when they know the importance of milk in their infant’s diet, and when they can afford to act upon their knowledge.

The important social and political question of how to preserve children as far as possible from the terrible blight of hereditary syphilis is one which, though coming strictly within the limits of our subject, cannot well be satisfactorily dealt with in this place. It is enough to record its grave importance, and the responsibility which attaches itself to any one who does what he can to prevent legislative interference with the diffusion of syphilitic disease among the adult population.

Very little attention has been paid hitherto to the important subject of the prevention of nervous disease in children [p.19] and young adults. Many of the more familiar of the so-called nervous diseases belong mainly to the stage of decline, and as for the most part people wear out at a rate roughly proportioned to their years, they are seen most commonly after the age of fifty. But these “old age” nervous diseases, as they may be called, often only very accidentally belong to the nervous system. The real fault is, as a rule, in the nutrition of the small arteries, in the condition of the valves of the heart, in the undue development of connective tissue everywhere, or in the kidneys and other leading organs. Faults of these various kinds manifest themselves through the nervous system by the injury they inflict upon it; for example, the rupture or the embolic closure of a vessel interferes with the nutrition, or destroys the integrity of certain cells or fibres of nervous tissue, and thus indirectly interferes with nervous function. Similarly, syphilitic nervous disease (so-called) rarely starts from true nerve-tissue, though it makes itself manifest by its influence on this tissue. It is not the fault of the nervous cells and fibres that they cease to work when starved by the blocking of their nutritive blood-vessel, or when ripped up by a clot of blood, or when squeezed out of life by a syphilitic deposit. Nor is it these indirect results of disease elsewhere to which preventive medicine should chiefly turn its attention, but to those conditions of faulty working of the nervous system itself to which the name of nervous disease properly and strictly belongs. Many of these conditions are common in childhood and young adult life, and are capable of being influenced for good, or of being deepened and intensified by external influences.

What is meant, or implied, exactly by the term” functional nervous disease,” can only be fully understood by those who are in possession of a clear and adequate conception of the position and purposes of the nervous system in the human organization. It is necessary to realize that this system controls not only all mental processes and sensation and voluntary motion, but also the functions of organic life, the action of every organ, the formation of every secretion, and the size [p.19] of every blood-vessel. All these purposes are accomplished by the aid of a something which we call” nervous force,” and which we know is developed or made in the nerve ganglia and distributed by the nerve fibres, very much as the force • which we call” electricity” is made in a battery and carried by the conductors. The ideal of nervous health is found in a well sustained and stable equilibrium between the work which the organism, as a whole and in all its several parts, has to perform, and in the equable production and diffusion of the force by which the work is performed. Wherever either the demand for nervous force is in excess of the power of manufacturing it in the nervous ganglia, or where the production of the force is naturally greatly in excess of the outlet provided for it, or where the several nervous centres work irregularly and inharmoniously, or upon too slight a stimulus, there we have departure from the ideal, and we are in the presence of nervous disorder. What we want is, that the work to be done and the force to do it should balance each other, and that the production and distribution of force should go on smoothly and evenly, and in response only to the normal stimuli. A very large part of the total amount of functional nervous disease is due to a fatal want of proportion between the demand for force and the power of producing it. People either want more force than they are able easily to make, and thus are stimulated or urged into efforts beyond their powers, or they have more than they can employ, and they are allowed to fret their hearts out for the want of something upon which to spend it. It is as if a battery of small size and few cells were expected to produce as much electricity as one twice its size, or, on the other hand, as if the current generated were stored under a condition of continually increasing tension.

It is too often overlooked that people differ from each other as much in their physiological as in their material wealth. While one has an income so assured and so large that his only duty in relation to it is to spend wisely and liberally, and to invest usefully, another has to struggle daily and [p.21] weekly to meet the necessities of the moment; his power of earning being small, he has to minimize expenditure and even to descend to the most petty economies to make his scanty pittance of an income supply the barest necessaries of life. In the same way there are people who seem to possess almost unlimited stores of nervous force; let them spend their strength as they will (and some of them spend it with prodigal lavishness in several ways at once), they cannot come to an end of their resources, and even when, for the moment, they are worn out and weary, they can count upon picking up again with extraordinary rapidity. On the other hand, there are people whose life is a long struggle against absolute physiological bankruptcy. They seem never to have quite enough nervous force, even for a routine life, and any unusual demand does for them entirely. Effort is not impossible to them; sometimes, under the stimulus of emulation or anxiety, they can even sustain an effort for some little time, but presently, when the stimulus ceases, they drop exhausted, and then take months or years to recuperate.

Happily, it is exceptional to see this condition in a marked degree persist through mature life, but it is by no means very rare to see it while growth and development are imposing their special taxes on the constitutional powers. Assuredly it is most unsafe to assume that all young people may, without danger, be urged to make the utmost effort in their power, or that stimulants of various kinds, emulation, prizes, even alcohol, may be used in order to elicit all the force they have without hesitation and without risk. The true remedy for insolvency is retrenchment, and what physiological paupers need is not stimulus, but rest and the least possible demand for such strength as they have. It is especially in towns, where children and young people are surrounded by influences at once debilitating and stimulating, that the danger of overtaxing and therefore exhausting the centres which manufacture nervous force needs to be remembered. In the country the opposite risk, that of supplying no adequate outlet for the nervous force when developed, is perhaps more frequently [p.22] present, but even there this is a danger which belongs properly to a later age. In considering how the special drawbacks of city life can best be dealt with, we have to ask, from the point of view of the people badly off for nervous force, how all the recreative and recuperating influences can be increased and the stimulating influences be diminished. The first part of the question is answered by improving the general hygienic condition, providing good air, open spaces, easy access to the country, simple nutritious food, and facilities for plenty of bathing, etc. The second part of the question, however, is a more complex matter. It is not easy to see how the life of a great city can ever be made unstimulating, or how the interests of the weak can, in city life, be specially considered. For it must be borne in mind that the stimulus of competition, of rival effort, and of constant variety, which belongs to town life, just suits the strong, and that it is they and not the weak ones who, in a community, will always rule. Therefore, so far as the adult population goes, there would seem to be but little possibility of materially modifying city life to suit the people of feeble nervous power. It must always be too keen and rapid to be really suitable for them. But for children, the difficulty is not quite equally great. Wise parents can do something, even among the poor, in the direction of promoting rest and long hours of sleep, of discouraging violent and unusual efforts, of avoiding all forms of stimulation, and especially by not placing the child in a position involving anxious effort and strain. The emulation of school life is often blamed for nervous and other weakness in children, and it seems impossible to doubt that to some it must inevitably be injurious. Here again, however, we have to accept the fact that in a community arrangements have to be made mainly to suit the fairly strong and vigorous, and not the exceptionally weak. Emulation and the stimulus it provides are great advantages to vigorous people, and in strict moderation they do no harm, even to the young, when they are strong. Primary education in public schools needs the help of some amount of emulation and competition, but even for the strong the danger of over [p.23] stimulation should be recognized. All that can be done in the way of specially protecting the exceptionally weak is that parents and heads of schools should recognize that there is an important minority of both boys and girls who are not equal to making any severe and continuous effort, to whom the stimulus of competition is positively injurious, and who require all, or almost all, the nervous force they can supply to meet the requirements of growth and development. It is, perhaps, too much the fashion to think of children, boys and girls, as if they were physically almost exactly like adults, only a few sizes smaller and proportionally less strong. From the point of view of the nervous system, at any rate, this view is certainly unsound. It overlooks the fact that during growth and development the nervous centres are themselves in a developing condition, learning to work together in response to certain stimuli, and in a certain subordination one to another. The machine is still in process of construction instead of being ready for use. It is not merely not so strong as a larger machine, it is not yet out of the workshop in which it is being made.

We meet with this fact again under a slightly different aspect when we turn to the consideration of the last of the essentials of health for children already enumerated, namely, a watchful care during their infancy and early childhood. It becomes very plain to any one who is able to consider and duly weigh familiar facts that by the very nature of their organization, children, even when healthy, are indefinitely more delicate, that is, more easily upset, than ordinarily healthy adults. They are more mobile, their physiological equilibrium is more unstable, and they suffer more quickly for any violation of physiological or hygienic laws. The processes of growth and development are making enormous demands upon their nutritive powers; they want for immediate use all the blood and nervous force that their blood-making organs and their nervous ganglia can supply them with, and the least check in either process threatens them with bankruptcy. To live from hand to mouth, as it were, each day by the help of good food, fresh [p.24] air, and good digestion, just contriving to meet the demands made upon their vital powers, is with them the rule, and not, as with adults, the condition of the exceptionally feeble.

It is not surprising, therefore, that slight departures from health, and especially those which interfere with the due performance of the nutritive processes, tell immediately upon a child’s health and vigor. Observant eyes can see at once that the manufacture of good red corpuscles has been checked with every slight disturbance of a child’s digestive or assimilative powers. Moreover, besides resenting hindrances to nutrition more than adults, they are far more prone to the occurrence of such hindrances. For instance, every mucous tract in a child is more liable to catarrh than the corresponding mucous membrane in adults. Notice how children suffer at once, and certainly, in their nasal and respiratory mucous membranes on coming from fresh pure air to the air of towns. It is a matter of common nursery observation that children on returning from a stay in the country always have pretty bad catarrhs within a week or so of their beginning to breathe the less pure air. Mothers are too well alive to this risk to forget it, and it certainly cannot in most cases be explained by “taking cold on the journey” or by want of care in any other direction. It is most unusual to see children take cold when they go from the city to the country, even at a colder season. The “coming home cold” is almost certainly due to the irritation of delicate mucous membranes by an air laden with smoke and other products of imperfect combustion. A corresponding susceptibility exists in the intestinal mucous tract. If, then, children are peculiarly prone both to disturbance of function and to the evil resulting from such disturbance, it is not to be wondered at that minute care is wanted to keep them in health till they acquire greater stability and more vigorous powers of resistance. When in addition to the delicacy common to all children there is superadded the immense drawback involved in trying to rear them from early infancy without their natural food, it becomes impossible to exaggerate the amount of care required if a successful result is desired. [p.25] The only thing which can at all make it possible to minimize the care needed is fresh country air, and with it one does occasionally see thriving vigorous children, to whom almost every other advantage has been wanting. But for town-bred infants care is an indispensable condition of health, and care of a kind far more minute and constant than can be given in any crèche or public nursery, or to any child put out to nurse for a few shillings a week. Where from any cause this minute and personal mother’s care cannot be given, a large proportion of the children are bound to die, in spite of anything which may be done for them by outside agencies.

It is evident, from all that has been said in considering the difficulties town-bred children have to contend with, that the labor involved in any considerable attempt to improve their condition must be great, and also that it is impossible, whatever may be done in this direction, ever to make town children as healthy as country ones. Much that may be attempted to diminish the dangers of city life has already been hinted at; as, for example, the multiplication of open spaces in towns, a proper system of drainage, and an abundant supply of good water. For young children, however, the most important remedy is that of encouraging their parents to get out of the town, or at any rate into the suburbs. Every facility that can be given to the poor to live a little distance from the most densely populated part of a town is of the greatest value to the children. Where land is abundant and cheap, the possession of a small garden even without a house, out of the town, would, by supplying out-door employment, be most valuable to both parents and children, especially to people above the poorest class, as, for instance, artisans and small traders.

Passing to the subject of a summer sanitarium for city children, a great many important practical questions at once arise. Any one familiar with children cannot think with entire satisfaction of any plan which involves separating them from their parents, and massing large numbers of them together. It may be feared that such a plan must be fraught with [p.26] danger to both health and morals: to health, if the children are intended to be very young, that is under four or five; and to morals, if they are intended to range between five and fourteen. The ideal summer outing for children is that each family should move from the city, but should preserve the continuity of its family life. This is impossible of attainment among the poor, but possibly some nearer approach to it might be reached than by massing together several hundred young children in any way which would preclude the possibility of giving them individual care. The boarding-out principle, which, so far at least as the children are concerned, works so well in England for the pauper children, might perhaps be adopted with modifications in the place of having one large building and grouping the children together. If a considerable number of people living in healthy country localities were registered as being each willing to receive during the summer one or two town children as boarders at a fixed rate, and a system of supervision were organized, such a plan would certainly be more natural and home-like, and therefore more acceptable to both parents and children, than a large central sanitarium could ever be. Children thus placed would also be much more easily provided with employment and amusement than they would be in an institution containing a very large number. They would enter into the duties and pleasures of the family with whom they boarded, and would feel themselves to be in surroundings not too unlike those in their own homes.

Where such a plan as this might, from the scanty country population or the bad sanitary condition of the country cottages, be impractible, it might be possible to arrange the sanitarium upon the plan of a number of detached houses, each to contain eight or ten children, and each to be under the direct care of one nurse or matron. By either of these methods the children would be secured an amount of personal and individual care and watching which it is impossible to get from the hard-worked staff of an immense institution. The routine, the formality, and even the noise, which are necessary parts of a large assemblage of children, are in themselves for a time trying to the health of those used to a free home life; and among American children, where by climatic and hereditary influences the tendency is towards undue restlessness and irritability of nerves, they would be more likely to do harm than in a more phlegmatic or stolid community. Town children everywhere, and perhaps American town children more than any others, are as a rule much more precocious than country children; mentally and physically they develop more rapidly, and what they need to make a change from city life of the greatest use to them is not the stimulation that goes with numbers, but the quietness and repose which belongs to country life as seen in a small family. Fresh air, the absence of noise, and comparative solitude, form the basis of such a life; and the combination of the three is probably as wholesome and recuperative to children as it is to adults. By many the stress of town life is felt more in the nervous system than in any other part of the organization; and to them especially one most important part of the value of a change to the country lies in the comparative quietness and solitude which it is possible to have there, but which would be practically destroyed for the inmates of a large sanitarium. If now in conclusion we turn back to the question with which we started, and ask ourselves again how can town children be kept healthy, we are obliged regretfully to admit, that after public and domestic hygiene has done its best, city life will always be full of special risks to the children of the poor, and that philanthropic effort cannot do very much directly towards diminishing those risks. It can do something, but it must be mainly through the parents, by improving their knowledge of what the children need, by raising their standard of comfort, and by deepening their sense of responsibility.

- 9 Jun - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Anderson's birth.

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, by Jo Manton. - book suggestion.

300px.jpg)

300px.jpg)

300px.jpg)