(source)

(source)

|

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel

(25 Apr 1769 - 12 Dec 1849)

French-English engineer and inventor who solved the historic problem of underwater tunneling through water-bearing strata and built the Thames Tunnel, the first tunnel in the world constructed under a navigable waterway.

|

Sir Isambard M. Brunel:

Block Machinery & the Thames Tunnel.

from Stories of Inventors and Discoverers (1860)

[p.285] The name of Brunel has now for two generations, from the commencement of this century to the present time, been identified with the progress and the application of mechanical and engineering science.

The elder Brunel, Isambard Mark, who displayed such diversity of genius for the minute and the vast, was born near Rouen, in 1769; and from his earliest boyhood showed mechanical tastes. When sent to the seminary of St. Nicaise at Rouen, he preferred the study of the exact sciences, mathematics, mechanics, and navigation, to the classics, and loved to pass his holidays in a joiner’s shop. At the age of twelve years he was proficient in turning, and in the construction of models of ships, machines, and musical instruments; he also made an octant, guided by the one belonging to his tutor and by a treatise on navigation; and at the age of fifteen he took such interest in astronomy as to observe the stars, greatly to the astonishment of the villagers. In 1786 he enlisted as a sailor, from which date up to 1793 he made several voyages to the West Indies, in which he used instruments of his own construction: he also made a pianoforte while the ship once lay at Guadaloupe.

Brunel’s first engineering work was a survey for the canal which now connects Lake Champlain with the river Hudson at Albany. He afterwards acted as an architect, and built one of the theatres at New York. He was employed on the forts erected for the defence of that city, and in the establishment of an arsenal and foundry; he also devised ingenious contrivances for boring cannon and moving large masses of metal with facility. He next visited England, where his first work was an autographic machine for copying maps, drawings, and written documents.

Brunel’s next work was his invention and construction of the assemblage of machines in Portsmouth Dockyard for the formation of Blocks employed in raising burdens, and particularly in the important service of moving the rigging of ships. There are sixteen different machines, all driven by the same steam-engine: seven cut or shape logs of elm or ash into [p.286] the shells of blocks, while nine fashion stems of lignum-vitæ into pulleys or sheaves, and form the iron pin, which being inserted, the block is complete. Four men with this machine turn out as many blocks as fourscore did formerly, and at less cost; and the supply has never failed, even though 1500 blocks are required in the rigging of a ship of the line. By adjustments, blocks can be manufactured of one hundred different sizes: thirty men can make one hundred per hour; and the machinery, by Maudslay, in twenty-five years required no repairs. It cost 46,000l.; and the saving per annum, in time of war, has been l. A second set of machinery was executed for the dockyard at Chatham. This assemblage of machines contains so many ingenious processes for gaining the proposed ends with the utmost accuracy and at the same time with the least possible labour, as to justify the opinion that it constitutes one of the noblest triumphs of mechanical skill. There is a set of magnificent models of this invention in the possession of the Navy Board: the machines work in succession, so as to begin and finish off a two-sheaved block, four inches in length, in the most perfect manner. A detailed account of the entire machinery is given in the Penny Cyclopaedia, Supplement 1.

Mr. Brunel next built in Chatham Dockyard the Steam Sawmill, in which he introduced Circular Saws, subsequently improved for cutting veneers. He also invented a machine for making seamless shoes; for nail-making; for twisting, measuring, and forming sewing-cotton into hanks; for ruling paper; a contrivance for cutting and shuffling cards without the aid of fingers, produced in reply to a playful request of Lady Spencer; a hydraulic packing-press; new methods and combinations for suspension-bridges; and a process for building wide and flat arches without centerings. He was employed in the construction of the first Ramsgate steamer; he was the first to suggest the advantage of steam-tugs to the Admiralty; and for ten years he carried on experiments in constructing a machine for using carbonic-acid gas as a motive power.

A popular writer of forty years since has left this graphic picture of his visit to Brunel’s workshops at Battersea: “In a small building on the left, I was attracted by the solemn action of a steam-engine of sixteen-horse or eighty-men power; and was ushered into a room where it turned, by means of bands, four wheels fringed with fine saws, two of eighteen feet in diameter, and two of nine feet. These circular saws were used for the purpose of separating veneers, and a more perfect operation was never performed. I beheld planks of mahogany and rosewood sawed into veneers the sixteenth of an inch thick, with a precision and grandeur of action which really was sublime. The same power at once turned these tremendous saws and drew their work from them. A large sheet of veneer, nine or ten feet long by two feet broad, was thus separated in about ten minutes; so even, and so uniform, that [p.287] it appeared more like a perfect work of Nature than one of human art. The force of those saws may be conceived, when it is known that the large ones revolve sixty-five times in a minute; hence 18x3·14 = 56·5 x 65 gives 3672 feet, or two-thirds of a mile, in a minute; whereas, if a sawyer’s tool gives thirty strokes of three feet in a minute, it is but ninety feet, or only the fortieth part of the steady force of Mr. Brunel’s saws.

“In another building I was shown his manufactory of shoes, which, like the other, is full of ingenuity, and, in regard to subdivision of labour, brings this fabric on a level with the oft-admired manufactory of pins. Every step in it is effected by the most elegant and precise machinery; while, as each operation is performed by one hand, so each shoe passes through twenty-five hands, who complete from the hide, as supplied by the currier, a hundred pairs of strong and well-finished shoes per day. All the details are performed by the ingenious application of the mechanic powers; and all the parts are characterised by precision, uniformity, and accuracy. As each man performs but one step in the process, which implies no knowledge of what is done by those who go before or follow him, so the persons employed are not shoemakers, but wounded soldiers, who are able to learn their respective duties in a few hours. The contract at which these shoes are delivered to Government is 6s. 6d. per pair, being at least 2s. less than what was paid previously for an unequal and cobbled article.”—Sir Richard Phillips’s Morning’s Walk from London to Kew.

Brunel is most popularly known by his great work of engineering construction,—the Thames Tunnel, consisting of a brick-arched double roadway under the river, between Wapping and Rotherhithe.

In 1799, an attempt was made to construct an archway under the Thames, from Gravesend to Tilbury, by Ralph Dodd, engineer; and in 1804 the “Thames Archway Company” commenced a similar work from Rotherhithe to Limehouse, under the direction of Vasey and Trevethick, two Cornish miners: the horizontal excavation had reached 1040 feet, when the ground broke in under the pressure of high tides, and the work was abandoned; fifty-four engineers declaring it to be impracticable to make a tunnel under the Thames of any useful size for commercial progression.

In 1814, when the Allied Sovereigns visited London, Brunel submitted to the Emperor of Russia a plan for a Tunnel under the Neva, by which the terrors of the breaking up of the ice of that river in the spring would have been obviated. The scheme, which he was not permitted to carry out at St. Petersburg, he was destined to execute in London.

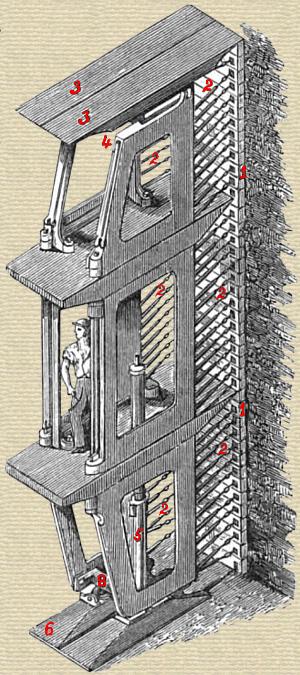

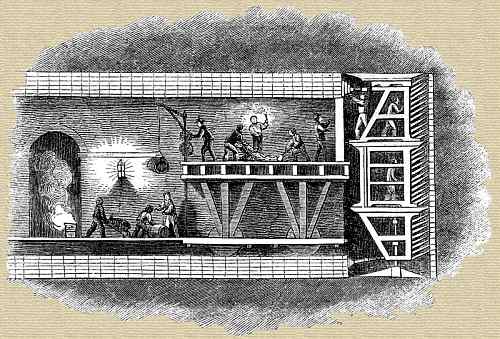

It was planned in 1823. Among the earliest subscribers to the scheme were the late Duke of Wellington and Dr. Wollaston; and in 1824 the “ Thames-Tunnel Company” was formed to execute the work. A brickwork cylinder, fifty feet in diameter, forty-two feet high, and three feet thick, was first commenced by Mr. Brunel, at 150 feet from the Rotherhithe side of [p.288] the river; and on March 2, 1825, a stone with a brass inscription-plate was laid in the brickwork. Upon this cylinder, computed to weigh 1000 tons, was set a powerful steam-engine, by which the earth was raised, and the water was drained from within it; the shaft was then sunk into the ground en masse, and completed to the depth of 65 feet; and at the depth of 63 feet the horizontal roadway was commenced, with an excavation larger than the interior of the old House of Commons. The plan of operation had been suggested to Brunel in 1814, by the bore of the sea-worm Teredo navalis in the keel of a ship; showing how, when the perforation was made by the worm, the sides were secured, and rendered impervious to water, by the insect lining the passage with a calcareous secretion. With the augur-formed head of the worm in view, Brunel employed a cast-iron “Shield,” containing thirty-six frames or cells, in each of which was a miner, who cut down the earth; and a bricklayer simultaneously built up from the back of the cell the brick arch, which was pressed forward by strong screws. Thus were completed, from Jan. 1, 1826, to April 27, 1827, 540 feet of the Tunnel. On May 18th the river burst into the works; but the opening was soon filled up with bags of clay, the water pumped out of the Tunnel, and the work resumed. At the length of 600 feet, the river again broke in, and six men were drowned.

The Tunnel was again emptied; but the work was discontinued for want of funds for seven years. Scores of plans were now proposed for its completion, and above 5000l. were raised by public subscription. By aid of a loan sanctioned by Parliament (mainly through the influence of the Duke of Wellington), the work was resumed, and a new shield constructed, March 1836, in which year were completed 117 feet; in 1837, only 29 feet; in 1838, 80 feet; in 1839, 194 feet; in 1840 (two mouths), 76 feet; and by November 1841 the remaining 60 feet, reaching to the shaft which had been sunk at Wapping. On March 24 Brunel was knighted by the Queen; on August 12 he passed through the Tunuel from shore to shore; and March 25, 1843, it was opened as a public thoroughfare. It is lighted with gas, and is open to passengers day and night, at one penny toll.

The Tunnel has cost about 454,000l.; to complete the carriage-descents would require 180,000l.: total, 634,000l. The dangers of the work were many: sometimes portions of the shield broke with the noise of a cannon-shot ; then alarming cries told of some irruption of earth or water: but the excavators were much more inconvenienced by fire than water; gas explosions frequently wrapping the place in a sheet of flame, strangely mingling with the water, and rendering the workmen [p.289] insensible. Yet, with all these perils, but seven lives were lost in constructing the Thames Tunnel; whereas nearly forty men were killed during the building of new London Bridge. In 1833, Mr. Brunel submitted to William IV., at St. James’s Palace, “An Exposition of the Facts and Circumstances relating to the Tunnel.” Brunel has also left a minute record of his great work: it is well described and illustrated in Weale’s Quarterly Papers on Engineering. A fine medal was struck at the completion of the work: obv. head of Brunel; rev. interior and longitudinal section of the Tunnel.

The width of the Tunnel is 35 feet; height, 20 feet; each archway and footpath, clear width, about 14 feet; thickness of earth between the crown of the arch and the bed of the river, about 15 feet. At full tide the floor of the Tunnel is 75 feet below the surface of the water.

Sir Isambard Brunel died at his house in Duke-street, Westminster, in 1849, aged 81. He left an only son, whose life and labours will be found recorded in a future sketch.

- Science Quotes by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel.

- 25 Apr - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Brunel's birth.

- Mark Isambard Brunel - Great Triumphs of Great Men (1875)

- Marc Isambard Brunel, by Paul Clements. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Marc Brunel.