(source)

(source)

|

Germain Sommeiller

(15 Mar 1815 - 11 Jul 1871)

French-Italian engineer who built the Mount Cenis Fréjus Rail Tunnel (1857-70) through the Alps. To accomplish boring the world's first important mountain tunnel, he introduced the first industrial-scale pneumatics for task.

|

Underground

or Life Below the Surface (1876)

XXXV.

THE MONT CENIS TUNNEL

[p.510] IT has been said with truth that “mountains interposed make enemies of nations.” In various parts of the world we find that mountain chains stand as barriers between different nations, and in many instances the boundaries thus formed by nature have remained unchanged for hundreds of years. On the map of Europe the most prominent mountain chain is that of the Alps, and it has stood as a separating line between nations for a long time. It is true that occasionally wars have been carried beyond these mountain chains, and conquests have been made in spite of them; but for practical purposes the chain of the Alps has been for centuries the separating line between France and Austria on the north, and Italy on the south. Sometimes the French possessions have extended to the south of the Alps, and sometimes Italy has extended her possessions to the north of that chain. Such possessions have never been held for a great length of time, and in one way or another they have fallen to the nation to whom they belonged by natural position.

Carriage roads were long since made across the Alps. In later years the railway has traversed these mountains, but the ascent is tedious and laborious, so that rapid communication was impossible. It remained for the science of the present day to overcome the obstacles which the mountains afforded, not by cutting away the Alps, but by piercing a passage through them.

[p.511] More than twenty years ago the attention of the French and Italian governments was called to the necessity of a tunnel through the Alps by which France and Italy should be connected. The project was discussed for some time, and finally a convention was formed between France and Italy for the purpose of undertaking the work. Four or five years were consumed in surveys and in the contemplation of plans. All sorts of objections were made, and a list of these objections forms a humorous page. One man contended that the heat would be so great in the centre of the mountain that the men would be roasted alive while working in the tunnel. Another was positive that the noxious gases and vapors arising in the tunnel would suffocate everybody. Another contended that rivers of water would be found in the mountain so great that they would overwhelm the workmen, and convert the tunnel into an enormous spring. And so on, one after another, the objections were heaped up, and there was at one time a prospect that the work would not be undertaken.

The actual work on the tunnel was begun on the Italian side in 1857, and a little afterwards work on the French side also commenced. A great deal of labor had been performed in locating the tunnel. A mountain chain is not a single line of mountains, like a row of potato hills; but it consists of a central back-bone of mountains, with other and smaller mountains on either side, so that a chain may often be a hundred or more miles in width. Now, in piercing a chain like the Alps, it is necessary to find a way among the outlying hills on each side through the valleys of the rivers that flow from the central chain. In this way the open-air railway is brought to the foot of one of the mountains forming the great central back-bone.

But a difficulty arises in finding two of these valleys directly opposite each other. You may follow a valley until you get to the very base of one of the highest mountains of the range, but on looking to the other side you may find no corresponding valley.

It was this peculiarity of all mountain chains that greatly [p.512] hindered the location of the Mont Cenis Tunnel. After much search, the best location was found to be by following the valley of the River Arc, on the northern side, and the River Dora, on the southern. A great many surveys were made,and it was finally discovered that the Arc and Dora, in their windings, were, at a certain point, less than eight miles apart. At this point, it was evident, Nature designed — if she had any design about it —that the great work should be constructed.

In 1867, while travelling north from Italy to France, I determined to pay a visit to the Mont Cenis Tunnel. It was said to be quite difficult to obtain a permit to enter the workings; but perseverance and letters of introduction will accomplish a great deal, and after a little delay I obtained what I asked for. I found it more convenient to visit the northern end of the tunnel for the reason that on the Italian side the workings were sixteen miles away from the regular line of travel, while those on the northern side were directly on the route of tourists.

A railway over Mont Cenis was then under construction, and nearly completed; but as it was not open for travelling, I made the transit in a carriage, just as many thousands of people had made it before me. The railway over the Alps is of itself a curiosity. In some places the ascent equals one foot in ten, so that great power was required for the locomotives to enable them to drag their burdens upward. The track was narrow, and it was peculiar in having three rails instead of two. The wheels of the carriages run on two rails only, just like wheels of carriages on other railways. The central rail was intended for the use of the locomotives, to assist their power of traction. The wheels were arranged on these locomotives in such a way as to grip the central rail with tremendous force, and the brakes were also so arranged that by pressing this central rail they could bring the carriages to a sudden stop in case of accident.

The line of the railway over Mont Cenis follows very nearly the carriage road, and occasionally crosses it. In some places [p.513] it passes through short tunnels, and in others it is roofed into avoid injury by snow. In crossing the mountain by this railway very little time is saved over the ordinary carriage route, while the latter is very much to be preferred on account of its comfort and the advantage it gives for observing the scenery. We were a party of four, and after an unhappy night in a dirty hotel at Susa, an old town founded by the Romans, and containing some ruins dating from the time of the Romans, we started on our journey.

Our night had been unhappy. Our breakfast was still more unhappy, and our bill for what the landlord facetiously termed our “entertainment” was the worst feature of all. The discomfiture of his establishment was greater than the comfort of the best hotel in Paris, and he charged us about twice the rate that any Parisian landlord would dare to ask. We consoled ourselves and settled our breakfast by getting up a magnificent row with him, threatening to break his head, and talked at least fifteen minutes in mingled patois of English, French, Italian, Russian, and Chinese. We did not succeed in having our bill reduced, but I am confident if what we said to that landlord remained ringing in his ears for twenty-four hours, it must have driven him to hopeless insanity.

We wound slowly up the mountain, with the top of our carriage thrown back, so that we could enjoy the view.

The Mont Cenis Pass is the least interesting of all the great passes of the Alps. Tourists complain of its tameness, but there are points where it is picturesque.

At places during the ascent we had some fine views of that portion of Italy which stretches away from the base of the mountain, and we tried to imagine that we could now and then catch a glimpse of the Mediterranean Sea. The rough mountains were piled above and around us, frequently in fantastic shapes, and we found the air getting steadily more and more cool as we made the ascent.

Finally on the summit, only a few hours after leaving a tropical temperature in Italy, we were riding amid fields of snow, and shivering in our travelling coats and thick shawls.

[p.514] The ascent was slow, but the descent on the French side was rapid. As we passed the boundary between Prance and Italy, our driver gathered his reins, and the horses went at full speed down the magnificent road. We left a cloud of dust filling the air behind us, and were whirled along so rapidly that I sometimes thought we might be tossed over one of the precipices in some of the short windings of the road. At every half mile there is a small shed, or house, known as the “refuge.” It is intended for travellers who are overtaken on the mountain, during the winter season, by violent snow-storms.

As it was summer we had no occasion to seek these refuges, but it was easy to see that they were of great advantage in protecting and saving life during the severer portion of the year.

At Lans-le-bourg we stopped at the French custom-house to undergo an examination; but our baggage was so small in quantity, and we manifested such a readiness to submit it to inspection, that the officers of customs did not detain us. Behind us was a carriage, in which were two American ladies, and they drove up a few moments before we started. They had that enormous amount of baggage peculiar to their sex and race, and protested that their trunks contained nothing of value. But the custom officers were inexorable, and as we drove away, the trunks of the ladies were being unpacked, and were undergoing a rigid examination. If you wish to avoid trouble at custom-houses when travelling in Europe, never carry a large amount of baggage, and never show the least hesitation to open it for inspection. Many a time have I found my baggage passed without examination, while the next man’s would be overhauled, and, as nearly as I could judge, only for the reason that he urged the officers not to look at it, and assured them that it contained nothing contraband.

At Modane we found the base of operations for the northern part of the tunnel, and here we halted to make our investigations. By the way, I never have been able to make out why the name of Mont Cenis should be attached to the famous tunnel, [p.515] since that mountain is about twenty miles away from it. The tunnel does not pass under Mont Cenis, but under three peaks called Col Frejus, Le Grand Vallon, and Col de la Roue, the first being on the French, the third being on the Italian slope, and the second about half way between the two. I suppose, however, that the tunnel was named after Mont Cenis because it is better known than any other summit or range in this neighborhood, and because it would be better to give it a name which does not belong to it at all, rather than naming it after any one of the three peaks deserving equal distinction.

Modane, or, more properly speaking, Fourneaux, was the base of operations. Fourneaux is a miserable little village in a narrow gorge in the valley of the Arc, and its inhabitants are chiefly remarkable for their deformity and idiocy. The Grand Vallon is eleven thousand feet above the sea level, and crowned with snow. Its sides are steep, and it would be quite impossible to carry a railway over it. The other mountains on the route are equally rugged in character, but their height above makes little difference with the workings carried on in their interior.

The Mont Cenis Tunnel is the largest in the world, extending from Fourneaux, on the French side, to Bardouneche, on the Italian side. When it was begun, with the ordinary system of hand drills, it was found that at the ordinary rate of progress, it would take thirty or forty years to finish the work. With an ordinary tunnel, where the elevation of earth or rock is not very great, shafts are sunk along the line, as before stated; but in this case it was impossible to sink these vertical shafts, on account of the great distance. A necessity arose for penetrating the rock much faster than by ordinary means, and there was also a necessity for supplying the workmen with fresh air.

These necessities led to Sommelier invention of drills worked by compressed air, and of the machinery for compressing the air. The machines have already been described in connection with the Hoosac Tunnel. A great many experiments [p.516] were made before the air could be successfully used; but finally, when they were completed, the work progressed rapidly. By means of the compressors that were worked by a stream of water from the mountain, the air was reduced to one sixth of its natural bulk,and thus, when liberated, it exercised an expansive force equal to six atmospheres. The compressing machines used at most tunnels to-day are simply enormous and very powerful pumps, but the machine of Sommelier used the weight of water. Twenty or more large iron tubes we replaced in an upright position. The “ head “ of the supply was far up the mountain side, and the water was brought to the machine in an iron pipe. A piston perfectly tight was fitted to the tube, the water was turned on, and its weight,added to the head it had received, compressed the air in the tube. As it was compressed, a valve was opened, through which it could escape into a reservoir. From this reservoir the air was conveyed in an iron pipe into the tunnel, where it was used to work the perforators.

We found that the entrance to the tunnel was quite a distance up the side of the mountain, and it was evident that considerable engineering skill would be required to bring the railway track thither when the work was completed. Opposite the mouth of the tunnel, my attention was called to a large target, made of boards painted white, and securely fastened against the rock. The target was used for the proper alignment of the work. At every foot of progress into the mountain, bearings were carefully taken. At night a Drummond light was placed in the centre of the target, so that it could be visible from the middle of the mountain.

It will be seen that it was a work requiring the utmost caution to lay out the route and direction of the tunnel through the mountain. A variation of a hundredth part of an inch at any point in the surveys would have changed the course of the working on one side or the other, so that the two ends would not meet. Bear in mind that these surveys were carried from the valley of the Arc to the valley of the Dora, — the opposite points being eight miles apart, — and the route [p.517] not through level fields and meadows, but over three rough and high mountains, where there was no path beyond that which the surveyors and their assistants laid out. And yet, so carefully was the work performed from the two sides, that the workings were brought together exactly, without a variation of a single foot.

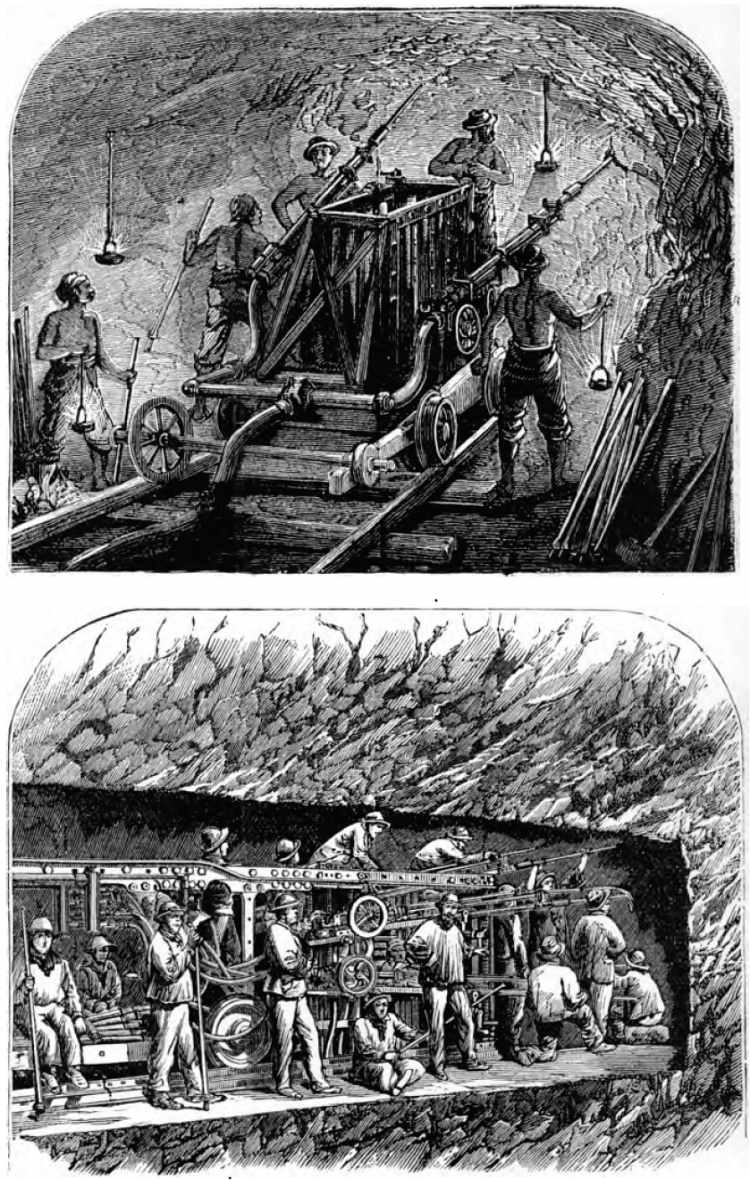

The entrance to the tunnel is about twenty-five feet wide, and the same in height. To go inside the workings, you are clad with a rubber suit, and supplied with a lamp, and accompanied by a guide. For some time after the working began, almost any one could be admitted; but it was found that the workmen were greatly hindered by frequent visits, so that the rules became very strict. No one could enter the tunnel, unless employed there, without a pass from the management, though it was not very difficult for a journalist or a person of influence or prominence to obtain admission. As fast as the work progressed, a double railway was laid down to carry in the materials used in the working, and to bring out the broken rock. There was a narrow sidewalk of flagged stone on each side. The pipes for the air were ranged along the side of the tunnel, and between the lines of the rails, in a deep trench, were the gas and water pipes.

Like all tunnels this one was damp, from the streams of water coming through the roof ; and if you wondered before entering, why you should be asked to wear a rubber coat,your wonder speedily ceased. At the time of my visit the workmen were nearly three miles from the entrance, — that is to say, the tunnel was finished for that distance, — while far about a quarter of a mile the men had cut the heading, but the upper part of the tunnel had not been opened.

The heading is the most difficult part of the work, and in all tunnel operations the workmen at the heading are kept sufficiently in advance of the enlargers, so that one party will not be in the other’s way.

The passage from the entrance through the finished portion was comparatively easy, but after you reached the newly-opened part you found it more difficult. There were wagon [p.518] and men moving to and fro, and fragments of rock were lying everywhere about. The space was narrow, and every little while you found yourself running much nearer a man or a mule than you wished to; unless you moved about very carefully, you were under the risk of being run over by a mule, or crushed by the wheels of a wagon.

The perforators kept up a perpetual din, and you could hardly hear yourself speak; and I have heard persons aver that you could not hear yourself think. The drill of the Mont Cenis machine stands on a carriage, which the Italians call the “Affusto,” and it strikes about two hundred blows a minute. Its force upon the rock is about two hundred pounds.

A stream of water is thrown upon the rock in to the drill-hole, to facilitate the perforating process.

The wear and tear of machinery in the tunnel were very great, owing to the hardness of the rock. Every fifteen minutes it was necessary to change the drills, and a great many affusti were worn out.

It was estimated that by the time the tunnel was completed four thousand machines were utterly worn out. At the entrance of the tunnel we saw a great many of these disabled affusti, reminding us of worn-out carriages around a stable.

With the exception that the workmen were clad in different costumes, and were shouting in French instead of English, the work was very much like that already described in the Hoosac Tunnel. Accidents were much more frequent in the Mont Cenis Tunnel than in the Hoosac Tunnel, for the reason that much less care was taken. It was said that nearly twelve hundred men lost their lives in the tunnel, or in connection with it, during the time of its construction, — at least, some of the workmen said so, — while the guides and directors insisted that the loss of life had not been more than one tenth of the number. Owing to the hardness of the rock the cost of the work was very great. Taking the average of the whole length of the tunnel, it was one thousand dollars a lineal yard, making a total, in round numbers, of fifteen millions of dollars.

[p.521] The expense was shared between the French and Italian governments, and the tunnel will form a bond of union between the two nations greater than could be made by any other use of the same amount of money. By the terms of the convention between the governments, the tunnel is to remain uninjured should France and Italy be engaged in hostilities against each other. The tunnel shortens the route of travel very materially, and where the route of travel is shortened the work of peace and good will among men is greatly facilitated.

A tunnel has been proposed for the Straits of Dover, between England and France, and several plans have been considered. The London Times stated, early in 1872, that a company has been formed and funds subscribed to the amount of some one hundred and fifty thousand pounds, with the immediate object of making a trial shaft, and driving a driftway on the English side about half a mile beyond low-water mark, with the view of proving the practicability of tunnelling under the Channel. The completion of this work will furnish data for calculating the cost of continuing the drift way from each shore to a junction in mid-channel, and capital will then be subscribed for that purpose, or for enlarging it to the size of an ordinary railway tunnel, as the engineers may deem most expedient.

The tunnel will be made through the lower or gray chalk chiefly, if not entirely, and by the adoption of machinery, of which the promoters of this company have recently made practical trials, it is expected the passage from shore to shore can be opened within three years from the time of commencing the work, and at a cost very considerably less than any previous estimates.

The same paper, referring to the proposed enterprise, gives the following details about railway and other tunnels: “The cost of existing tunnels has been governed by such various conditions of locality and soil, that they can have little bearing upon the present question. It may be worth while, nevertheless, to cite a few prominent examples. The Mont Cenis [p.522] Tunnel has cost one hundred and ninety-five pounds per linear yard, which would amount, for a length of twenty-two miles, to seven millions four hundred and fifty thousand four hundred pounds. The three most costly tunnels made in England have been the Kilsby, the Salt wood, and the Bletchingley, each of which was executed in treacherous strata, giving out large quantities of water. In making the Kilsby Tunnel a hidden quicksand was discovered, by which the works were drowned out. For a considerable time all pumping apparatus, appeared insufficient, but by the employment of one thousand two hundred and fifty men, two hundred horses, and thirteen steam engines, working night and day for eight months, one thousand eight hundred gallons per minute were raised from the quicksand alone. The cost of the work was raised from ninety thousand pounds, the original estimate, to three hundred and fifty thousand pounds, or one hundred and forty-five pounds per yard for two thousand four hundred yards. The same rate of expense for twenty-two miles would amount to five millions six hundred and forty-six thousand six hundred and twenty pounds. The Saltwood Tunnel cost one hundred and eighteen pounds per yard, the Bletchingley seventy-two pounds; or for twenty-two miles, four millions five hundred and sixty-eight thousand nine hundred and sixty pounds, and two millions seven hundred and eighty-seven thousand eight hundred and forty pounds, respectively.

“The cost of railway tunnels in France has varied from thirty pounds per yard — being that of Terre Noire, on the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean Railway, to ninety-five pounds per yard, that of Batignolles, near Paris, on the Chemin de Fer de l’Ouest. In Belgium, Braine le Comte Tunnel cost forty-six pounds per metre, and the tunnels on the Liege and Verviers line fifty pounds per metre. In Switzerland the very difficult Hauenstein Tunnel between Basle and Berne cost eighty pounds a yard.

“In America, the Hoosac Tunnel, in Massachusetts, through mica slate, mixed with quartz, has up to this time cost [p.523] one hundred and eighty pounds per yard, and the Moorhouse Tunnel, in New Zealand, through lava streams and beds of tufa, intersected by vertical dikes of phonolite, cost sixty-eight pounds fifteen shillings per yard. It will be a convenient standard of comparison for these amounts if we remember that twenty-five pounds per yard would represent very nearly a million sterling for the twenty-two miles. Any estimate for the Channel Tunnel must at present be purely conjectural, and an estimate professing to embrace contingencies must be more conjectural than any other; but it is reckoned that the work, if practicable at all, could be completed within five years of time, and for five millions of money.”

- 15 Mar - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Sommeiller's birth.

- The Mont Cenis Tunnel - Rock Boring: excerpt from Discoveries and Invention of the Nineteenth Century (1903).

- Surveying the Mont Cenis Tunnel - How can tunnels meet when bored from two sides of a mountain? From Our Iron Roads (1883).

- Today in Science History event description for the opening of the railway through the Mont Cenis tunnel on 19 Sep 1871.