(source)

(source)

|

David Douglas

(25 Jun 1799 - 12 Jul 1834)

Scottish botanist who was one of the founding fathers of British forestry. He scoured North America for plants, and introduced many to Britain.

|

Life of David Douglas

Extracts from A Brief Memoir, by Sir William Jackson Hooker

from David Douglas, Botanist at Hawaii (1919)

[p.7] “It is not willingly that the following record of the successful labors of Mr. David Douglas in the field of natural history, and of his lamented death, has been so long withheld from the public: a circumstance the more to be regretted, because his melancholy and untimely fate excited a degree of interest in the scientific world, which has been rarely equaled, especially towards one who had hitherto been almost unknown to fame as to fortune. But the writer of this article was anxious to satisfy public curiosity by the mention of some further particulars than what related merely to Mr. Douglas’s botanical discoveries; and this could scarcely be done but through the medium of those friends whose personal acquaintance was of long standing, and especially such as knew something of his early life. This has at length been accomplished, through the kindness of Mr. Douglas’s elder brother, Mr. John Douglas, and of Mr. Booth, the very skilful and scientific gardener at Carchew, the seat of Sir Charles Lemon, Bart. It is to Mr. Booth, indeed, that I am indebted for almost all that relates to the subject of this memoir, previous to his entering the service of the Horticultural Society, and for copies of some letters, as well as several particulars relative to his future career.

[p.8] David Douglas was born at Scone*, near Perth, in 1799, being the son of John Douglas and Jean Drummond, his wife. His father was a stone mason, possessed of good abilities and a store of general information, rarely surpassed by persons in his sphere of life. His family consisted of three daughters and as many sons, of whom, the subject of this notice was the second. At about three years of age he was sent to a school in the village, where the good old dame.

‘Gentle of heart, not knowing well to rule,’ soon found herself mastered by her high-spirited little scholar, who

‘Much had grieved on that ill-fated morn, ‘When he was first to school reluctant borne,’ and took every opportunity of showing his dislike to the restraint, by playing truant or defying the worthy lady’s authority.

At the parish school of Kinnoul, kept by Mr. Wilson, whither he was soon sent, David Douglas evinced a similar preference to fishing and bird-nesting over book learning; he was often punished for coming late, not knowing his lessons, and playing the truant; but no chastisement affected him so much as being kept in school after the usual hour of dismissal. His boyish days were not remarkable for any particular incidents. Like others at his time of life he was lively and active, and never failed of playing his part in the usual sports of the village. A taste for rambling, and much fondness for objects of natural history being, however, very strongly evinced. He collected all sorts of birds, though he often found it difficult to maintain some of these [p.9] favorites, especially the hawks and owls. For the sake of feeding a nest of the latter, the poor boy, after exhausting all his skill in catching mice and small birds, used frequently to spend the daily penny with which he should have procured bread for his own lunch, in buying bullock’s liver for his owlets, though a walk of six miles to and from school might well have sharpened his youthful appetite. He was also much attached to fishing and very expert at it, and when he could not obtain proper tackle, had recourse to the simple means of a willow wand, string, and crooked pin, with which he was often successful.

From his earliest years nothing, it is said, gave Douglas so much delight as conversing about travelers and foreign countries, and the books which pleased him best were Sinbad the Sailor and Robinson Crusoe. The decided taste which he showed for gardening and collecting plants caused him to be employed at the age of ten or eleven years, in the common operations of the nursery ground, at Scone, under the superintendence of his kind friend and master, Mr. Beattie, with the ultimate view of his becoming a gardener. Here his independent, active and mischievous disposition sometimes led him into quarrels with the other boys, who on complaining of David to their master, only received the reply, “I like a deevil better than a dult,” an answer which showed he was a favorite, and put a stop to further accusations. In the gardens of the Earl of Mansfield, he served a seven years’ apprenticeship, during which time it is admitted by all who knew him, that no one could be more industrious and anxious to excell than he was, his whole heart and mind being devoted to the attainment of a thorough knowledge of his business. The first department in which he was placed was a flower garden, at that time under the superintendence of Mr. McGillivray, a young man who had received a tolerable education, and was pretty well acquainted with the names of plants and the rudiments of botany. From him Douglas gathered a great deal of [p.10] information, and being gifted with an excellent memory, he soon became as familiar with the collection of plants at Scone as his instructor.

Here the subject of this notice found himself in a situation altogether to his mind, and here, it may be said, he acquired the taste for botanical pursuits which he so ardently followed in after life. He had always a fondness for books, and when the labor of the day was over, the evenings, in winter, invariably found him engaged in the perusal of such works as he had obtained from his friends and acquaintances, or in making extracts from them of portions which took his fancy, and which he would afterwards commit to memory. In summer again, the evenings were usually devoted to short botanical excursions, in company with such of the other young men as were of a similar turn of mind to himself, but whether he then had any intention of becoming a botanical collector, we have now no means of ascertaining. He had a small garden at home, where he deposited the living plants that he brought home. It may be stated that these excursions were never pursued on a Sabbath day, his father having strictly prohibited young Douglas so doing, and this rule he at no time broke. The hours which may be called his own, were spent in arranging his specimens, and in reading with avidity all the works on travels and natural history, to which he could obtain access. Having applied to an old friend for a loan of some books on these subjects, the gentleman (Mr. Scott), to David’s surprise, placed a Bible in his hands, accompanied with the truly kind admonition, ‘There, David, I cannot recommend a better or more important book for your perusal.’

It has frequently occurred to us, when admiring the many beautiful productions with which the subject of this memoir has enriched our gardens, that, but for his intercourse with two individuals, Messrs. R. and J. Brown, of the Perth Nursery, these acquisitions, in all probability, would have been

‘The flowers on desert isle that perish.’

[p.11] At this period of Douglas’s life, these gentlemen were very intimate with Mr. Beattie, and their visits to Scone afforded opportunities to him to gain their acquaintance. Both were good British botanists, and so fond of the study, as annually to devote a part of the summer to botanizing in the Highlands; hence their excursions were often the subject of conversation, and it is believed, that from hearing them recount their adventures, and describe the romantic scenery of the places they had visited in search of plants, Douglas secretly formed the resolution of imitating their example.

Having completed the customary term in the ornamental department, he was moved to the forcing and kitchen garden, in the affairs of which he appeared to take as lively an interest as he had previously done in those of the flower garden. Lee’s Introduction to Botany and Don’s Catalogue, his former text books, if they may be so termed, were now laid aside, and Nicol’s Gardener’s Calendar taken in their stead. The useful publications of Mr. Loudon, which ought to be in the hands of every young gardener, had not then made their appearance; so that his means of gaining a theoretical knowledge of his business were very limited, when compared with the facilities of the present day; but, what was of more consequence to one in his situation, he had ample scope for making himself master of the practical part, and it is but justice to state that, when he had finished his apprenticeship, he only wanted age and experience in the management of men, to qualify him for undertaking a situation of the first importance.

His active habits and obliging disposition gained the friendship of Mr. Beattie, by whom he was recommended to the late Mr. Alexander Stewart, gardener at Valleyfield, near Culross, the seat of the late Sir Robert Preston, a place then celebrated for a very select collection of plants. Thither David Douglas went in 1818, after having spent the preceding winter months in a private school in Perth, revising [p.12] especially such rules of arithmetic as he thought might be useful, and in which he either had found or considered himself deficient. He was not long in his new situation when a fresh impulse seized him. The kitchen garden lost its attraction, and his mind became wholly bent on botany, more especially as regarded exotic plants, of which we believe one of the very best private collections in Scotland was then cultivated at Valleyfield. Mr. Stewart finding him careful of the plants committed to his charge, and desirous of improvement, encouraged him by every means in his power. He treated him with kindness and allowed him to participate in the advantages which he himself derived from having access to Sir R. Preston’s botanical library, a privilege of the utmost value to one circumstanced like Douglas, and endowed with such faculties of mind and memory as he possessed. He remained about two years at Valleyfield, being foreman during the last twelvemonth to Mr. Stewart, when he made application and succeeded in gaining admission to the Botanic Garden at Glasgow.

In this improving situation it is almost needless to say, that he spent his time most advantageously and with so much industry and application to his professional duties as to have gained the esteem of all who knew him, and more especially of the able and intelligent Curator of that establishment, Mr. Stewart Murray, who always evinced the deepest interest in Douglas’s success in life. Whilst in this situation he was a diligent attendant at the botanical lectures given by the Professor of Botany in the hall of the garden, and was his (the Professor’s) favorite companion in some distant excursions to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, where his great activity, undaunted courage, singular abstemiousness, and energetic zeal, at once pointed him out as an individual eminently calculated to do himself credit as a scientific traveler.

It was our privilege and that of Mr. Murray, to recommend Mr. Douglas to Joseph Sabine, Esq., the Honorary [p.13] Secretary of the Horticultural Society, as a botanical collector; and to London he directed his course accordingly in the spring of 1823. His first destination was China, but intelligence having about that time been received of a rupture between the British and Chinese, he was despatched in the latter end of May, to the United States, where he procured many fine plants, including a large number of specimens of various oaks, and greatly increased the society’s collection of fruit trees. He returned late in the autumn of the same year, and in 1824, an opportunity having offered through the Hudson’s Bay Company of sending him to explore the botanical riches of the country in North-West America, adjoining the Columbia river, and southward towards California, he sailed in July for the purpose of prosecuting this mission.

We are now come to the most interesting period of Mr. Douglas’s life, when he was about to undertake a long voyage, and to explore remote regions, hitherto untrodden by the foot of any naturalist. In these situations, far indeed from the abodes of civilized society, frequently with no other companion than a faithful dog, or a wild Indian as a guide, we should have known little or nothing of his adventures, were it not for a Journal which he kept with great care (considering the difficulties, not to say dangers, which so frequently beset him in his long and painful journeyings), and which has been deposited in the library of the Horticultural Society of London.”

From this point onwards, Sir (then Dr.) W. J. Hooker in his memoir gives lengthy extracts from the Journal kept by Douglas during his wanderings in the North-West parts of America in the years 1824, 1825, 1826, and 1827. As the chief object in issuing this pamphlet is to give some particulars regarding Douglas’s travels in Hawaii, it is not thought desirable to reproduce his Journal of travels and adventures covering the above-mentioned period. Those who are interested in botany and the early explorations of the [p.14] North-West Coast will find the Journal given at length, as also a condensed account of same, in the volume entitled “Douglas’ Journal,’ edited by W. Wilks, Secretary of the Royal Horticultural Society, and published in London, 1914, by William Wesley & Son. Most of it will also be found in Vol. II. of the Hawaiian Spectator, published in 1839.

Suffice it to say here that Douglas sailed from the Thames by the Hudson’s Bay Co. brig “William and Ann” on July 25th, 1824, touching at Madeira, Rio, Juan Fernandez, and the Galapagos Islands en route and reaching the Columbia River on April 7th, 1825. On his arrival he devoted his full time and energies down to March 20th, 1827, to the exploration of the Columbia River region. During his stay, he traveled over 7000 miles by canoe, on foot of on horseback, undergoing many hardships and dangers. He was often reduced to living on roots such as were used by the Indians, and as might be expected, his clothes were often worn to rags through traveling in the rough country found in that region. He discovered many new trees, plants, birds and mammals. Among the trees were the fir which will always bear his name, and several species of pine, e.g., Pinus amabilis (Abies amabilis), Pinus grandis, P. insignis, P. Lambertiana, P. Menziesii, P. nobilis (Abies nobilis), P. ponderosa, P. Sabiana, etc., many species of ‘ribes,’ or currants, now common in gardens, the California vulture, and the California sheep.

In March, 1827, in company with Dr. McLoughlin, of the Hudson’s Bay Co., he left Fort Vancouver and traveled overland to York Factory, Hudson’s Bay. On the way, he met Sir John Franklin at Norway House. It may be mentioned that owing to his own stock of clothes being worn out, before starting on his overland journey, the Hudson’s Bay people at Fort Vancouver furnished him with a suit of bright red Royal Stewart tartan (coat, vest and pants) and it was in this gaudy outfit that Douglas made his way across the continent, much to the surprise, no doubt, of the Indians [p.15] whom he met on his way. Sailing from Hudson’s Bay on Sept. 15th, Douglas reached Portsmouth on Oct. 11th, 1827.

From the great number of plants and seeds which Douglas had sent or brought home with him from the North-West Coast, the Royal Horticultural Society, according to Hon. Secretary W. Wilks, raised 210 distinct species in the Society’s gardens, 80 of which being considered to be only “Botanical curiosities” were “abandoned” and 120 species were grown on and distributed to all parts of the world.

Douglas on his arrival in London was made much of in scientific circles, and was for some time a lion in fashionable society. He was elected a Fellow of the Linnean, Geological and Zoological Societies without payment of fees, and in 1828, Dr. Lindley dedicated to him the genus of Douglasia among the primrose tribe.

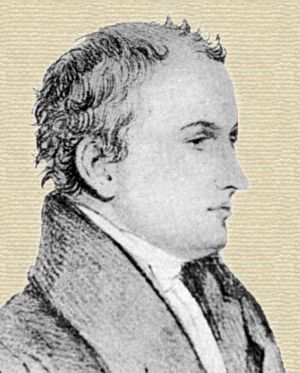

From a life sketch, formerly belonging to his brother James Douglas. Now in Vancouver, B.C., Museum. Permission of Miss Edge, Vancouver, B.C.

Notwithstanding the flattering attention with which he was received in England, Douglas was glad to accept the offer of the Horticultural Society to return once more on an exploration trip in the same general district of the North-West Coast of America as before. He left England for the last time in the autumn of 1829. On his arrival at the Columbia River he found that owing to the Indians being on the war path, he would not be able to extend his travels very far into the interior. He therefore left the Columbia River and went to California in the Dryad, and landed at Monterey in 1831. His intention was to return to the Columbia River in the autumn; being unable to find any ship or other means of transport, he was compelled to spend another season in California, making various excursions to the interior and to the south as far as Santa Barbara, and perhaps further down the coast to San Diego, the furthest south Mission station in California. Finally he sailed to the Sandwich Islands (now known as the Hawaiian Islands). In those days there were many vessels trading between the islands and the coast of California.

From Honolulu he despatched to England his California [p.16] collection of seeds and plants. On this his first visit to the Sandwich Islands, he wished to explore the high mountains of the group, but owing to being laid up with an attack of rheumatism, the result of hardships which he had undergone in the North-West Coast, he was unable to undertake any hill climbing. After a short stay at the Islands, he returned to the Columbia River, and explored the Fraser River district. His first experience of the Sandwich Islands made him desirous of more thoroughly investigating the botanical treasures that are to be found there. Accordingly he sailed from the Columbia River on October 18th, 1833, arriving at Honolulu, or Fair Haven, as it was then sometimes called, on the 23rd December, 1833, immediately leaving for the big island of Hawaii, which he reached on January 2nd, 1834.

Outside of the account of his ascent of Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa and visit to Kilauea volcano, given in the Journal which he forwarded to his brother John Douglas, little is known of David Douglas’s wanderings in the Hawaiian group. If he visited the Island of Maui and ascended the extinct crater of Haleakala, it would have been very interesting for this generation to be able to read his experiences on such a trip. He at all events must have done considerable botanizing on the island of Oahu, where Honolulu, the capital, is situated, but of this no record has come down to our time.

On 12th July, 1834, while travelling along the upper edge of the forest in the Hamakua-Hilo district of the island of Hawaii, Douglas fell into a pit used for trapping wild cattle, and was gored to death by a bull. His mangled remains were brought to Honolulu and buried in the Kawaiahao Church Cemetery. The exact spot where he was interred is not now known. The Rev. Henry H. Parker, who was pastor of Kawaiahao Church, from June 28th, 1863, down to January, 1918, states that he does not know the site of Douglas’s burial, as in former years no record was kept of the burials in Kawaiahao churchyard: In 1856, Mr. Julius L. [p.17] Brenchley, M.A., F.R.G.S., author of “the cruise of H.M.S. Curacoa among the South Sea Islands,” who had previously visited the islands in company with Jules Remy, editor of “Ka Mooolelo o Hawaii,” forwarded from England a tombstone of white marble to Honolulu for the purpose of being erected over Douglas’s burial place. The exact spot of burial being unknown, or for some other reason, the tombstone has been placed on the face of the south-west wall of Kawaiahao Native Church, on the right of the entrance door. Tropical sunshine and showers of many years have had their effect on the lettering of the tablet, and in a few more years from this date, the inscription will become illegible.

A monument to Douglas’s memory was erected in the churchyard at New Scone, near his birthplace. It was erected, as the inscription on it states, ‘by subscriptions among the botanists of Europe.’ The compiler of this pamphlet on a visit to Scotland in 1903, paid a visit to New Scone and had a photograph taken of this monument, a copy thereof being printed herein. The monument stands in the burying ground attached to the old parish church, wherein took place the coronation of Charles II., the last monarch to be crowned in Scotland.

In the “Douglas Journal,” published by the Royal Horticultural Society in 1914, there is given a list, drawn up by Mr. W. Wilks, Hon. Secretary, of some two hundred varieties of plants introduced by Douglas, and as Professor G. S. Boulger has remarked, this large number of trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants will help more than any stone monument to perpetuate his memory. His dried plants are divided between the Hookerian and Bentham herbaria at Kew, the Lindley herbarium at Cambridge, and that of the British Museum. Original portraits of Douglas are to be found at Kew, at the Linnean Society, London, and at the Vancouver, B.C., Museum. In the Royal Society’s catalogue, Douglas is credited with fourteen papers, which are in the transactions and journals of the Royal, Linnean, Geographical, [p.18] Zoological and Horticultural Societies. The only one of these which specially interests residents of the Hawaiian Islands is that on the Volcanoes in the Sandwich Islands, which appeared in the Geographical Society’s Journal IV., 1834, pp. 333-343. This paper has been republished in booklet form.

In the Flora of Hawaii, Douglas has been remembered by his fellow botanists through names given to the following plants, viz.:

native name Maieli or Puakeawe.

2. Pandanus Douglasii—Gaudichaud.

native name Hala or Lauhala.

3. Argyrophyton Douglasii—Hooker.

native name Ahinahina, the Silver Sword plant of the foreigner, and now usually styled Argyroxiphium Sandwicense DC.

4. Gymnotheca Douglasii—T. Moore.

Marattia Douglasii—Baker.

Stibasia Douglasii—Bresl.

different synonyms given to the fern known as the “Pala.”

- Science Quotes by David Douglas.

- 25 Jun - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Douglas's birth.

- Biography of David Douglas - The Botanical Collector, from True Tales of Travel and Adventure, Valour and Virtue (1884).

- The Collector: David Douglas and the Natural History of the Northwest, by Ann Lindsay Mitchell and Syd House. - book suggestion.

- David Douglas: Explorer and Botanist, by William Moorwood. - book suggestion.

- Olla-Piska: Tales of David Douglas, by Margaret J. Anderson (for ages 9-12). - book suggestion.

- Traveler in a Vanished Landscape, The Life & Times of David Douglas, by William Moorwood. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for David Douglas.