The Opening of Brooklyn Bridge

On Thursday 24 May 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge over the East River in New York was ceremoniously opened, attended by vast crowds there to see processions, decorations, a speech by President Arthur and addresses by civic leaders, all concluded with a fireworks celebration. The city of Brooklyn was formally united with New York City.

The weather was very pleasant, reported in The New York Times as, “A fairer day for the ceremony could not have been chosen. The sky was cloudless, and the heat from the brightly shining sun was tempered by a cool breeze.”

Thousands of visitors flocked from all around to witness the momentous event. Special trains were arranged from Philadelphia, Easton, and Long Island, and the regular trains were so packed that there was barely any standing room. An estimated over 50,000 people arrived by rail, and even more came by Long Island Sound boats and ferry boats, adding to the massive crowds of residents from both of the cities the bridge connected.

The bridge’s opening was primarily a celebration for Brooklyn, with New York’s involvement limited mainly to the large crowd that filled its streets. While some businesses closed or stopped operations around noon, most stores remained open, attracting numerous patrons as they would on any regular day. The combination of visitors from outside and curious New Yorkers created a festive atmosphere in Madison Square, Broadway, and City Hall Park, where thousands gathered. People crowded the windows, balconies, and rooftops of buildings along Broadway. American flags were proudly displayed, giving the city a holiday feel. Although only a few buildings were decorated, including the Sun and Staats-Zeitung offices near the New York approach with festoons of bunting, the overall ambiance was lively. Superintendent Walling and Inspector Murray efficiently coordinated the police arrangements to ensure smooth traffic flow. About 9 a.m., as workmen removed the fence in front of the New York approach, it was replaced by a line of about 50 policemen guarding the opening.

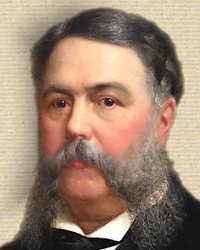

At 11:15 a.m., an assembly call was heard from the Seventh Regiment’s armory. Thirty minutes later, the regiment emerged, dressed in their summer uniforms of gray coats, white trousers, and white helmets, escorting the 24 carriages of the President, Governor, Mayor, and other V.I.Ps. The parade was led by Cappa’s band of 70 musicians augmented by another 22 in the drum corps. They trooped down Madison Avenue, displaying their perfect formations and long strides, which they were known for. The regiment halted at Twenty-third Street and Fifth Avenue, where two companies welcomed the guests of the day. The first carriage held President Chester Arthur and Mayor Franklin Edson, whom the crowd hailed with cheers when it appeared. The President greeted them in return by lifting his hat. The subsequent carriages accommodated various government officials, trustees, and notable figures. The procession, preceded by a squad of mounted policemen, then passed down Fifth Avenue and turned into Broadway.

President Arthur, the center of attention, received cheers and applause from the crowds lining the way and waving from windows. Near Eighteenth Street, a brief moment of excitement ensued when the horses pulling the President and Mayor’s carriage became frightened, but a quick-thinking police officer brought them under control. President Arthur remained calm throughout the incident, and once the horses settled, the procession continued amidst enthusiastic applause.

City Hall Park and Printing-house Square were tightly packed with spectators, in an almost impenetrable mass. Ticket holders faced difficulties reaching the bridge amidst the confusion. Every available rooftop and window offered views, with some adventurous individuals even climbing tall telephone poles for a better vantage point. The police worked hard to maintain necessary clearances.

At 1:30 p.m., the parade reached City Hall and came to a halt. The guests disembarked from their carriages, with President Arthur receiving further welcoming cheers from the crowd. The spectators eagerly looked for Governor Cleveland, ready to cheer him as well, but his portly form went unrecognized until, with Gen. Slocum, he joined the Presidential party. The Aldermen present, each walking carrying their staff of office, were led by Sergeant-at-Arms Chambers, whose long staff was surmounted by a gilt eagle. They were accompanied on foot by various department heads and minor officials. (Alderman Fitzpatrick, who had opposed the bridge, and attended a funeral that day, said he did not find it fitting to participate.)

With the music of a lively march from the band, the procession continued, described by The New York Times as “like a huge giant gray and black serpent”, wending its way to the bridge entrance.

By 1:50 p.m., the majority of the regiment had marched onto the bridge. Walking arm-in-arm ahead of the procession were President Arthur and Mayor Edson. Ahead of them a water-carrier, with a yellow pail and a rack of glasses, seemed so unaware of his proximity to greatness, that he mistook the cheers for the President as if for him, and smiled in return to the crowd. The newspaper report noted that the “President had to step carefully to avoid the water-carrier’s heels”!

The procession disappeared into the bridge entrance, followed by the rest of the public that held tickets purchased in advance. Those without tickets but eager to witness the event paid $2 to ticket speculators for entry. For a brief period, some wily individuals used white business cards of the correct shape as makeshift tickets—but only until the trick was discovered and thwarted.

As the President and Governor reached the halfway point to the New York pier, a commotion arose, and Orator Abram S. Hewitt struggled to move closer to the head of the procession. The rooftops and upper windows of buildings were filled with eager sightseers, many using opera glasses and telescopes to get a better view of the parade. The procession’s view from the bridge was spectacular. The harbor was adorned with decorated vessels, flags, and bunting. Ferry-boats, tugs, and small boats on the rivers proudly displayed flags. The pier-heads offered prime spots for spectators, and the docked vessels were filled with people who had claimed their spots hours before the festivities began. The warships, including the Tennessee, Kearsarge, Yantic, Vandalia, Minnesota, and Saratoga, were anchored in a line below the bridge, each adorned with flags and bunting that extended from stem to stern and above the mast tops.

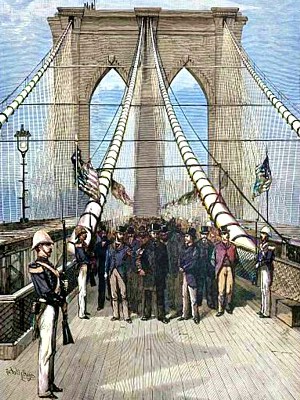

To the west of the New York pier, the Seventh Regiment halted and formed two ranks, presenting arms as the civilians passed by. The band played “Hail to the Chief” under the pier arches. At 2 p.m., the head of the column reached the pier, where several bridge trustees, led by Acting President William C. Kingsley, warmly welcomed the President and Governor. As the procession continued after a brief pause, a Signal Corps officer dipped a signal flag, and within seconds, a puff of smoke and a loud report erupted from a port-hole of the Tennessee, marking the start of a 21-gun salute. The other warships, as well as the Navy Yard and Castle William on Governor’s Island, joined in the salute. On the river side of the pier, the members of the Fifth United States Artillery presented arms. The procession then reached the center of the magnificent bridge. Upon reaching the Brooklyn pier, Mayor Low and the Brooklyn authorities stepped forward, linking arms with the Mayors of both cities. A detachment of marines guarded the Brooklyn pier, while the Twenty-third Regiment stood in formation. The men presented arms, the band played “Hail to the Chief,” and the immense crowd on the Brooklyn approach erupted in cheers. The President and other dignitaries took their seats in the building at the Brooklyn approach, but the majority of those who had crossed over were unable to get close enough to witness the interior due to the overwhelming crowd. The congestion extended back nearly halfway to the pier.

The next day, The New York Times reported on these activities and the excitement of the big event, as can be expected, as the front page news, in the Friday, 25 May 1883 edition.

The second image above comes from the collection of Currier & Ives chromolithographs held by the Library of Congress. The print carries the title, “The Great East River Suspension Bridge” and subtitled, “Connecting the Cities of New York and Brooklyn - View from New York, Looking South.” The splendid panorama includes the Bay and part of New York. Also visible and labeled on an original full-size print, are the New York Bridge Tower in the foreground, the Statue of Liberty on Bedloes Island in the Bay, steam-powered ferries, Coney Island, Governor’s Island, Staten Island, the Produce Exchange, Trinity Church, and the New York Entrance to the bridge. (Although the copyright year on the print was 1885, the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty was not ready until the following year. So Webmaster wonders if perhaps the edifice was included on the print, in anticipation of its completion.)

- Today in Science History, event description for opening of Brooklyn Bridge on 24 May 1883.

- Today in Science History, short biography for John Roebling born on 12 Jun 1806 (Chief engineer and designer of the Brooklyn Bridge).

- Today in Science History, short biography for Washington Roebling born on 26 May 1837 (John Roebling's son, who finished the Brooklyn Bridge).