ANTICIPATIONS

from The Spectator (1902)

[p.247] A VERY entertaining book might be written by collecting together all the cases in which poets and play-writers and novelists have anticipated the triumphs of later science.

A correspondent of the Pall Mall Gazette has just called attention to such a case, in which the Spanish dramatist Calderon uttered “a very clear prevision of Marconi's wireless telegraphy.” The passage in question occurs in Act II. of El Medico de su Honra, and may be freely translated as follows:

Of course Calderon referred in this passage to the well-known principle of resonance, and it is hardly accurate to twist his words into a prophecy of wireless telegraphy.

A much closer approximation to Mr. Marconi's discovery, however, is to be found in the writings of a contemporary of Calderon, Strada, the learned Jesuit historian whose “Prolusiones” were published at Rome in the year following Shakespeare's death. Strada tells us how two friends carried on their correspondence

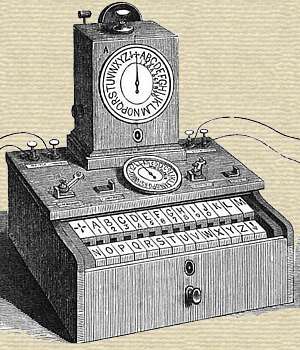

Of course the modern reader sees in this a premonition of our telegraph, in which the electric impulse, propagated in the older fashion along a wire or in the new way by a simple radiation in the ether, causes a magnetic needle to move according to the signals transmitted by the sender of the message. Strada went on to describe how these two friends made a kind of “alphabetic telegraph,” as one of the predecessors of the telephone was called,—a dial-face with the letters of the alphabet round its edge, and a needle in the midst which could be made to point to any of them at will. These correspondents saw no need for wires, or even for the simpler apparatus which Mr. Marconi requires.

Even Mr. Marconi has not yet attained such simplicity as this, though Professor Ayrton (as we lately pointed out) believes that we shall reach an even higher standard one day.

A classical instance of the novelist's “intelligent anticipation” of future scientific discoveries is afforded by Swift in the inimitable “Gulliver's Travels.” In the third part of that immortal work he describes the discovery of two satellites of Mars by the Laputan astronomers. When Swift wrote astronomy had not advanced greatly beyond Huygens's contentment with the twelve bodies—six planets and six satellites —which made up the “perfect number” of the solar system. Certainly no one suspected that Mars had moons of its own. Thus Swift made a very wild guess when he announced of the Laputan philosophers:

Not only were there no grounds for the prediction of two satellites, but such an estimate of their distance from the planet was unprecedented: it was as if our moon should lie within twenty thousand miles of the earth, and rise and set twice or thrice in the twenty-four hours. Nothing could be more improbable. Yet in 1877 Professor Asaph Hall, with the great Washington equatorial, actually discovered two tiny satellites of Mars, whose distances from the planet are 1½ and 3½ diameters, whilst their periods are 7½ and 30 hours respectively. The agreement with Swift's guess is in the main so remarkable that it is hardly possible to ascribe it to mere accident; and yet these satellites are the merest points of light, which no telescope in existence before Herschel's day could possibly have shown. Some people assert that Swift had some extra-scientific means of knowing the truth by crystal-gazing, or astral currents, or one of the various uncanny methods which come within the scope of the Society for Psychical Research. Like Herodotus, one prefers not to say what one thinks of this interesting theory.

Another curious anticipation of astronomical discovery is to be seen in Shelley's beautiful poem, “The Witch of Atlas,” where he transforms the mother of his heroine into—

It was long supposed that this was merely a blunder. Shelley had heard of the recent discovery of certain minor planets, or asteroids, in the great gap between Mars and Jupiter, and he had made a slight mistake in his reference to them. No doubt his apology would have been the same as Dr. Johnson's for his famous mistake about the horse's pastern—“Ignorance, Madam, pure ignorance!” But about three years ago it was discovered, for the first time, that at least one minor planet does revolve between the orbits of the earth and Mars. This is the famous Eros, which comes nearer to the earth than any celestial body but the moon, and which is expected to throw so much light on the actual dimensions of the solar system. Thus Shelley was not a mere blunderer, but a prophet,—as he always held that the true poet was bound to be,

We can only glance at many other cases of similar anticipations which are known to students of this branch of literature. A notable instance is Fénelon's suggestion of photography in his imaginary travels.

Here, as in many similar cases, it seems reasonable to suppose that “the wish was father to the thought”; in other words, we may say that the thoughtful writer described a desirable thing which seemed possible, and left the future man of science to devise the means for attaining it. It is hardly necessary to think with Sir Thomas Browne that “many mysteries ascribed to our own inventions have been the courteous revelation of spirits.”

At least, we need not ascribe such an origin to so natural an anticipation as that of the Paris “moving platform” by Rabelais in his “Isle of Odes.” It has been suggested, with somewhat less show of reason, that Rabelais gave the world its first hint of the possibility of the phonograph in his account of the frozen words that startled Pantagruel and his joyous crew on their voyage to the oracle of the Holy Bottle.

A recent [p.248] correspondence in Nature pointed out that Virgil had spoken of liquid air, whilst Lucian had described the inhabitants of the moon, seventeen centuries ago, as drinking “air squeezed or compressed into a goblet,” where it formed a kind of dew. The reader cannot but think of Professor Dewar's vacuum-jacketed vessels, though even the thirsty American visitor who complains so bitterly of the lack of ice and cool drinks in the English summer has not yet ventured on liquid air as a constituent of his cobblers and sangarees.

In the “New Atlantis” Bacon predicts submarine boats and “some degrees of flying is the air,” which last phrase is a clear anticipation of M. Santos-Dumont. Of course Bacon can hardly be taken as a fair instance of the mere novelist, any more than Mr. H. G. Wells; it was his business to anticipate.

Ben Jonson, however, has a curious account of the submarine boat or torpedo in one of his plays, which is open to no such objection. This was supposed to be constructed by the Dutch, then our chief maritime rival:—

With a snug nose, and has a nimble tail

Made like an auger, with which tail she wriggles

Between the costs of a ship, and sinks it straight.”

But the most extraordinary book of all is that which the Marquis of Worcester published in 1655, with its forecasts of telegraphs, steam-engines, flying and calculating machines, dynamite shells and torpedoes, ironclads, quick-firing guns, and revolvers. Unfortunately, the Marquis omitted to explain how any of these things could be made, and so we may fairly include his “Century of Inventions” among the forecasts of fiction.