Cover (click to enlarge) |

GENERAL GUIDETO THEBRITISH MUSEUMNATURAL HISTORY(Published 1898) |

Extract from A General Guide to the British Museum (1898)

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

THE British Museum dates its actual foundation from the year 1753, when an Act of Parliament was passed “for the purchase of the Museum or Collection of Sir Hans Sloane, and of the Harleian Collection of Manuscripts, and for providing One General Repository for the better Reception and more convenient Use of the said Collections and of the Cottonian Library and of the Additions thereto.”

Sir Hans Sloane, an eminent physician in London, was for sixteen years President of the Royal College of Physicians, and in 1727 succeeded Sir Isaac Newton in the Presidential Chair of the Royal Society. He was throughout his long life a diligent and miscellaneous collector, having, as stated in the Preamble of the Act of Incorporation of the Museum, “through the course of many years, with great labour and expense, gathered together whatever could be procured, either in our own or foreign countries, that was rare and curious.” His collection, which at the time of his death in 1753 was contained in his residence, the Manor House, Chelsea, consisted of “books, drawings, manuscripts, prints, medals and coins, ancient and modern antiquities, seals, cameos and intaglios, precious stones, agates, jaspers, vessels of agate and jasper, crystals, mathematical instruments, pictures, and other things,” which latter included numerous zoological and geological specimens, and an extensive herbarium of dried plants preserved in 310 large folio volumes.

According to the terms of Sir Hans Sloane's will, this collection was purchased for the sum or �20,000, far below its intrinsic value, in order “that it might be preserved and maintained, not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public to all posterity.”

The valuable collection of manuscripts formed by Sir Robert Cotton at the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth centuries, was already the property of the nation, having been presented by his grandson, Sir John Cotton, in the year 1700. The Harleian Collection was obtained by purchase at the same time as the Sloanian, and the three were brought together under the designation of “the British Museum,” placed under the care of a body of trustees*, and lodged in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, purchased for their reception in 1754. The Museum was opened to the public on the 15th of January, 1759. Admission to the galleries of antiquities and natural history was at first by ticket only on application in writing, and limited to ten persons, for each of three hours in the day. Visitors were not allowed to inspect the cases at their leisure, but were conducted through the galleries by officers of the house. The hours of admission were subsequently extended; but it was not until the year 1810 that the Museum was freely accessible to the general public for three days in the week, from ten to four o'clock. The present daily opening, with longer hours in summer, dates only from 1879.

At the time of the foundation of the Museum, the site allotted seemed amply sufficient for its purposes; but gradually, as the Collections of all kinds increased, they outgrew the limits, not only of the original Montagu House, but even of its successor, the present classical building, completed in 1845 from the designs of Sir Robert Smirke. The erection of the magnificent reading-room in 1857 disposed for a time of the difficulty of finding accommodation for the ever-growing library; but the keepers of other departments continued urgent in their demands for more space, and after much discussion of rival plans for keeping the collections together and obtaining the needful extension of room by acquiring the property immediately around the old Museum, or for severing the collections and removing a portion to another building, the latter course was finally decided upon. At a special general meeting of the trustees, held on the 21st of January, 1860, attended by many members of the Government in their official capacity, a resolution, moved by the First Lord of the Treasury, was carried “That it is expedient that the Natural History Collection he removed from the British Museum, inasmuch as such an arrangement would be attended with considerably less expense than would be incurred by providing a sufficient additional space in immediate contiguity to the present building of the British Museum.”

The House of Commons, in the Session of 1863, sanctioned the purchase of part of the site of the International Exhibition of 1862 at South Kensington, with a view to appropriating it to the purpose of a Museum of Natural History.

In January, 1864, the Commissioners of Her Majesty's Works issued an advertisement for designs for a Natural History Museum and a Patent Museum, to be erected on part of the land thus acquired, a plan which had been prepared by Mr. Hunt in September, 1862, from Professor Owen's suggestions, being proposed as a model in respect to dimensions and internal arrangement.

The plans of the various competitors were submitted to Her Majesty's Commissioners of Works, who awarded prizes to three of the number, giving precedence to that of Captain Francis Fowke, R.E., and then referred the three premiated plans to the Trustees of the British Museum. As the internal arrangements in Captain Fowke's plan did not meet with the approval of the Museum officers, he was desired to modify them in conformity with the requirements of the Trustees. He was engaged in this labour when his death occurred, in September, 1865.

Early in the year 1866, Mr. Alfred Waterhouse was invited by the Chief Commissioner of Works to take up the unfinished work of Captain Fowkes but he found himself unable to complete the plan to his own satisfaction, and in February, 1868, he was commissioned to form a fresh design, embodying the requirements of the officers of the Natural History Departments of the Museum.

Mr. Waterhouse was not long in submitting to the Trustees his plan and model of the building, with a disposition of galleries as required, and these were formally accepted by the Trustees in April, 1868. It was not, however, until February, 1871, that the working plans had been thoroughly considered, and received the final approval of the Trustees.

The actual work of erection was commenced in the year 1873, and

the building was handed over to the Trustees of the British Museum by

Her Majesty's Commissioner of Works in the month of June, 1880.

Immediately that the exhibition cases were completed, and the galleries

were sufficiently dry to receive the collections, the great labour of

removing the Natural History Collection from Bloomsbury was commenced.

The departments of Geology, Mineralogy and Botany, were arranged in

their respective sections of the Museum in the course of the year 1880,

and the portion of the Museum which contained these departments was

first opened to the public on April 18th, 1881. It was not until the

following year that the cases destined to receive the larger

collections of the Zoological Department were sufficiently complete to

allow of these collections following, and three more years were

required before all the rooms could be brought into a state fitted for

public inspection. The last that was opened was the gallery devoted to

British Zoology, in May, 1886.

* The Trustees under the Act of Incorporation were the

Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, the Speaker of the House

of Commons, the Bishop of London, and the principal Officers of State

for the time being; six representatives of Founders' families; the

Presidents of the Royal Society and College of Physicians; and fifteen

other Trustees to be elected by them. Subsequently, the Presidents of

the Society of Antiquaries and of the Royal Academy of Arts, a Trustee

by special nomination of the Sovereign,. and three more family Trustees

were added to the Board.

(click to enlarge)

DESCRIPTION OF THE BUILDING

The following description of the structure has been contributed by Mr. Waterhouse:-

“The New Natural History Museum will, from its position, always be more or less identified with the International Exhibition of 1862, which occupied the whole of the site between the Horticultural Gardens and Cromwell Road. It was at one time thought that a portion, at any rate, of the Exhibition buildings could with advantage have been converted into a Museum of Natural History. Parliament, however decided against the preservation of any part of these buildings, and they were accordingly entirely removed.

“In designing the present building, Captain Fowke’s original idea of employing terra-cotta was always kept in view, though the blocks were reduced in size, so as to obviate, as far as possible, the objection to the employment of this material, arising from its liability to twist in burning. For this and other reasons the architect abandoned the idea of a Renaissance building, and fell back on the earlier Romanesque style which prevailed largely in Lombardy and the Rhineland from the tenth to the end of the twelfth century.

“In 1873, a contract was entered into by the Government with Messrs. George Baker and Sons, of Lambeth, for the erection of the building at a cost of �352,000. Other subsequent contracts have been entered into by the Treasury, especially one for the erection of the towers, which in the first instance it was decided to omit.

“On looking at the exterior of the building, one of the first points which strikes a spectator is that the site is lower than the street. This arises from the fact that the whole surface of the ground between the three roads was excavated for the Exhibition building of 1862, and it was not thought desirable, for economical considerations, to refill the space. The building is set back 100 feet from the Cromwell Road, and is approached by two inclined planes, curved on plan and supported by arches, forming carriage-ways. Between the two are broad flights of Craigleith stone steps, for the use of those approaching the building on foot. The extreme length of the front is 675 feet, and the height of the towers is 192 feet. The return fronts, east and west, beyond the end pavilions, have not yet been erected.

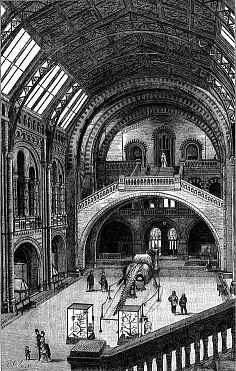

“On entering the main portal, the visitor has before him the great central apartment of the Museum (170 feet long, by 97 feet wide, and 72 feet high), which it is intended to use as an Index or Typical Museum. The double arch in the immediate foreground which spans the nave (57 feet wide), carries the staircase from the first to the second floor. Opposite the spectator, at the end of the hall, is the first flight of the staircase. 20 feet wide, which rises from the ground to the first floor. The galleries over the side recesses form the connection between the two staircases, and are also intended for exhibition space, as are also the floor of the main hall and the side recesses under the galleries. The arches under the side flights of the main staircase at the end of the hall lead into another large apartment, cruciform on plan, intended for the exhibition of specimens of British Natural History, with an extreme length of 97 by 77 feet measured into the arms of the cross.

“Branching out of the Central Hall, near its southern extremity, are two long galleries, each 278 feet 6 in. long by 50 feet wide. These galleries are repeated on the first floor, and in a modified form on the second floor. They are divided into bays by coupled piers arranged in two rows down the length of the galleries, and planned in such a manner as to allow of upright cases being placed back to back between the piers and the outer walls, so as to get the best possible light upon the objects displayed in the cases with the least amount of reflection from the glass, and leaving the central space free as a passage. Owing to the nature of the specimens exhibited in one or two of these galleries, requiring for their exhibition rather table-cases than wall-cases, advantage has only been taken to a limited extent of this disposition of the plan. These terra-cotta piers, however, are constructively necessary, not only to conceal the iron supports for the floor above, but to prevent these supports being affected in case of fire. Behind these galleries on the ground floor are a series of toplighted galleries, devoted, on the east side to Geology and Palaeontology, and on the west to Zoology.

“The towers on the north of the building have each a central smoke-shaft from the heating apparatus, the boilers of which are placed in the basement, immediately between the towers, while the space surrounding the smoke-shafts is used for drawing off the vitiated air from the various galleries contiguous thereto. The front galleries are ventilated into the front towers, which form the crowning feature of the main front. These towers also contain, above the second floor, various rooms for the work of the different departments, and on the topmost storey large cisterns for the purpose of always having at hand a considerable storage of water in case of fire. On the western side of the building, where it is intended that the Zoological collection shall be placed, the ornamentation of the terra-cotta (which will be found very varied both within and without the building) has been based exclusively on living organisms. On the east side, where Geology and Palaeontology find a home, the terra-cotta ornamentation has been derived from extinct specimens.

“The Museum is the largest, if not, indeed; the only, modem building in which terra-cotta has been exclusively used for external fa�ades and interior wall-surfaces, including all the varied decoration which this involves.&dquo;

The space covered by the building itself, including the detached portion behind, which contains the collections of animals preserved in spirit, is nearly four acres.

The whole ground on which the Museum stands, including the gardens which surround it on the south, east and west sides, is 12 acres and 635 yards. The gardens are open to the public whenever the Museum itself is open, under certain regulations which are posted at the entrance gates.

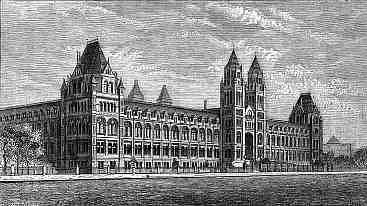

* In judging the appearance of the exterior of the building, it should be remembered that these fronts are required to complete the design, as the externally unsightly brick galleries which run back from the main front, and are now conspicuous when the Museum is seen from either west or east, are intended to be concealed by them. (Above: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, from the south-west, showing part of the west front, not yet completed.) 7 June - short

biography, births, deaths

and events on date founding of the British Museum

7 June - short

biography, births, deaths

and events on date founding of the British Museum