|

Alfred Maul

(1864 - 1941)

German engineer and inventor who spent a number of years working on launching rockets capable of taking aerial photograph and return safely to the ground.

|

Taking Photographs From a Skyrocket

from The Book of Modern Marvels (1917)

AMONG the aids to the conduct of the war that have been proposed in Germany is the photography of the enemy's positions by the flight of rockets carrying cameras. The invention is less expensive and can be sent up closer to the enemy without provoking attack than a captive balloon, dirigible or aeroplane. Besides, it is not so dependent upon the wind as a kite. When the inventor, Alfred Maul, began his experiments fifteen years ago, he found, as he tells us in an article appearing in Umschan, that the ordinary rocket can hardly carry a considerable weight, and so he was obliged to devise one of greater strength. His first invention was a shell closed above and open below containing a firmly compressed powder composition in which was a deep opening. Ignition developed a considerable volume of gas, which gas pressed down upon the atmospheric air* [No! see footnote], thus causing the rocket to rise. In a shot the initial velocity is the highest, whereas in the rocket the initial velocity is low but increases until the charge is burnt out. This occurs in about one and one-half to two and one-half seconds, but the rocket continues to rise, through the force generated, from six to nine seconds.

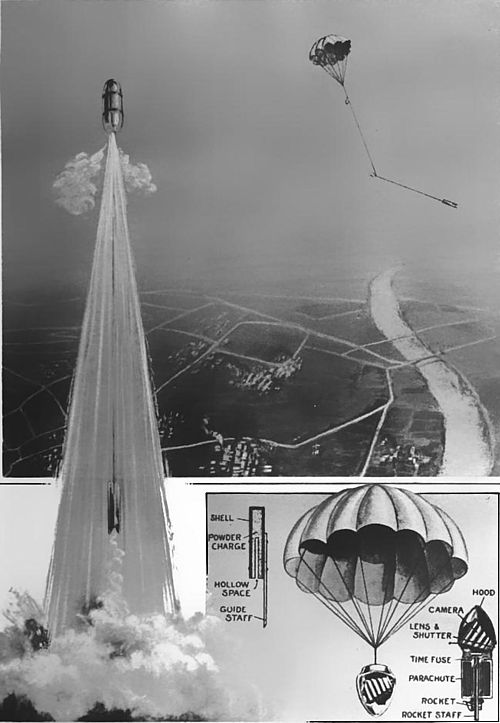

In his first camera experiments Mr. Maul used two small rockets combined. Here the rotary camera, which could take a picture about one and one-half inches square and had an oblique downward inclination, was in a hood above the rockets. At the sides of the rockets were two chambers containing parachutes of unequal size. The guide-staff had two vanes at its lower end, like an arrow, to prevent rotation and change of direction of the lens. At the highest point of the flight a time-fuse raised the shutter and threw out the smaller parachute. Just before landing, the larger parachute was opened. The double rocket could carry a load of over half a pound and rose about one thousand feet.

Failures accompanied successes in the tests. Rockets exploded, parachutes dropped at the wrong moment and much costly apparatus was destroyed, before the inventor saw the cause of his misfortunes, which was that the time taken for ascent depended on the density and moisture of the air. The exposure and release of the parachutes were, therefore, arranged independently of the period of ascent, by making the upper part of the hood resilient and equipping it with an electric contact device. When the rocket paused for a moment at its highest point of ascent, the contact opened the shutter and directly afterward threw out the first parachute. This proving successful, the photographic apparatus was enlarged to a diameter of eight and one-half inches; the plates were made four and three-quarters by four and three-quarters inches, the focal distance was also four and three-quarters inches. The length of the equipment was now over thirteen feet and the weight thirteen pounds. As the apparatus was still inclined to rotate on its axis corrective experiments were made, but the rocket proved unable to carry the weight of a special governing apparatus. Finally, a gyroscopic device was arranged which works automatically when the rocket rises and does not permit rotation.

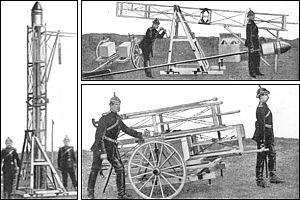

The present apparatus can rise to a height of sixteen hundred feet. Its length is twenty feet, its weight about fifty-five pounds, and the pictures are seven and one-quarter inches square. Its parts are shown on the preceding page. The guide-staff about fifteen feet long is made in two united but easily separable parts, the upper being bolted to the rocket, the lower carrying the vanes, as shown.

When ready for use the rocket is mounted on a collapsible, heavy frame carrying the sighting device and weighing about eight hundred and eighty pounds. The rocket is ignited by a distant electric device. The weight immediately runs down and the charge is fired, driving the rocket up one thousand, six hundred feet in eight seconds. When near the highest point of ascent the contact in the top of the hood opens the instantaneous shutter and releases the parachute. As the parachute opens, the rocket divides into two parts, connected by a thirty-two-foot belt. The hood and camera hang just under the parachute, while the container and staff swing about thirty-two feet below. The parachute, relieved of extra weight, lands the camera without jar in sixty seconds.

[* Webmaster note: As any physics student now should know, a rocket works by the forward momentum that results from expelling the mass of exhaust gas at high speed in the opposite direction, according to the law of conservation of momentum. We all now know that rockets firing in the vacuum of space have nothing to “press down upon.”]

- Camera Rocket U.S. Patent 757,825 - issued to Alfred Maul on 19 Apr 1904.

- Camera Rocket U.S. Patent 847,198 - issued to Alfred Maul on 14 Mar1907.