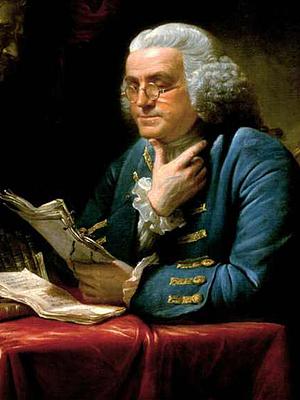

Benjamin Franklin, Postmaster-General

Appointed 26 Jul 1775

On 26 Jul 1775, a critical decision was made by the Second Continental Congress to appoint Benjamin Franklin as the first Postmaster General of the United Colonies, a position that would later evolve into what we now know as the Postmaster General of the United States. This action reflected the burgeoning autonomy and unity of the American colonies during a tumultuous period of revolutionary fervor.

By this time, Benjamin Franklin was already a prominent figure in the American colonies, esteemed as a polymath for his diverse pursuits. His credentials encompassed a vast range of fields—science, invention, writing, publishing, philosophy, and public service—making him an embodiment of the Enlightenment spirit. Importantly, Franklin’s extensive experience in postal affairs rendered him an obvious choice for the pivotal role of Postmaster General.

Before his appointment, Franklin had already accumulated valuable experience in managing postal services. He was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, and his impressive service led to his appointment by the British Crown as joint postmaster general for the colonies in 1753. However, his revolutionary activities led to his dismissal from this role in 1774, a little over a year before his appointment by the Continental Congress.

Franklin’s appointment as Postmaster General was strategically significant in several ways. Firstly, it was a clear manifestation of the Continental Congress’s aspiration to establish a solid, intercolonial communication network. In the tumult of impending war with Britain, a reliable postal system would serve not just as a practical necessity, but as a symbol of unity and resistance against British control.

Secondly, Franklin’s appointment led to the development of a postal route independent of the British postal system. Given the increasing tensions between Britain and the colonies, such a step was critical to ensuring secure and confidential communication between different parts of the American colonies.

Benjamin Franklin’s tenure as Postmaster General was marked by his characteristic inventiveness and efficiency, qualities which he brought to bear in reshaping and expanding the colonial postal system. . Previously, mail delivery was inconsistent, often left to casual couriers without a structured system. The task before him was to create an independent and efficient postal service capable of securely connecting the thirteen colonies, which stretched over 1,500 miles from north to south. Communication was vital for the Revolutionary cause. It was imperative for coordinating military strategies, disseminating political news, and facilitating commerce among the colonies.

In his new role, Franklin implemented several crucial reforms and improvements in the postal service. Franklin first focused on establishing a robust postal route system. In his previous role as the joint postmaster general for the colonies under the British Crown, he had already significantly improved mail delivery. Drawing on this experience, he expanded the mail routes beyond the major cities, extending into rural and frontier areas. He implemented regular, scheduled delivery and pickup times, making the service more predictable and reliable. He expanded the postal network, establishing numerous new post offices and significantly improving mail delivery times.

Under Franklin’s leadership, the postal service began to operate routes by night, significantly cutting down on delivery times. These were covered by riders or stage wagons, depending on the volume of mail. By introducing this change, Franklin increased the speed of communication between the colonies, a crucial factor during the Revolutionary War.

In terms of management, Franklin introduced the first rate chart, which standardized the rates for letters and packages, considering factors such as the distance covered, weight of the package and types of mail. This move brought about consistency and predictability in postal charges, an important step towards creating a professional and trustworthy postal service.

Franklin also emphasized the security of the postal service, knowing it was of paramount importance due to the sensitive nature of many communications sent during the Revolutionary War. Having standardized the process, setting up regular routes, schedules, and procedures he had already reduced the opportunity for mishandling and loss of mail. He added more mechanisms to prevent the loss and mishandling of letters, ensuring their secure transit from one location to another.

To further secure the mail, Franklin introduced the position of “surveyor” for the postal routes. This was an inspector-like role, in which an appointed person would oversee the operations of different routes and post offices, ensuring they adhered to the set standards. The surveyors were responsible for checking that mail was handled properly, reducing opportunities for theft and loss.

He also implemented a more systematic and secure way of recording the transit of mail. Postmasters were required to keep detailed records of mails received and dispatched, making it easier to track the progress of a letter or package and identify any problems or delays.

Additionally, Franklin put more emphasis on the training of postal employees. He understood that a secure and reliable postal system required knowledgeable and responsible workers. Therefore, he invested in the education and training of postal workers, teaching them the importance of their roles and the need to handle mail correctly and professionally.

In terms of physical security, Franklin recognized the importance of secure post offices and strong mailbags. He ensured post offices were built and equipped in a way that protected the mail from damage, theft, or loss. Mailbags used for transport were robust and designed to withstand the rigors of travel.

Lastly, Franklin prioritized the confidentiality of mail. At a time when sensitive information was often transmitted through letters, it was crucial that this information did not fall into the wrong hands, particularly during the Revolutionary War. Franklin made it clear that tampering with or prying into someone else’s mail was a serious offence, and he put measures in place to ensure the privacy of correspondence. He thus established a level of trust and reliability in the postal service, which was crucial in an era when letters were the primary means of long-distance communication.

Moreover, Franklin recognized the importance of international connections. He made arrangements to maintain communication with overseas destinations, particularly France, a critical ally during the War of Independence.

His tenure ended on 7 Nov 1776, when he was dispatched by the Continental Congress to France as one of America’s first diplomats. His main mission in France was to seek military and financial assistance for the fledgling American nation in its Revolutionary War against Britain.

Franklin’s diplomatic skills, charm, scientific reputation, and passion for the American cause made him an effective ambassador. His popularity and diplomacy greatly contributed to the securing of the Treaty of Alliance with France in 1778, a pivotal agreement which provided important military support and recognized the independence of the United States.

In Franklin’s absence, the Continental Congress appointed his son-in-law, Richard Bache, to succeed him as Postmaster General. Bache served until 1782 when he was succeeded by Ebenezer Hazard.

While Franklin’s term as Postmaster General was relatively brief, his innovative work and effective leadership laid a strong foundation for the future development of the postal system. His efforts had a long-lasting impact, emphasized the importance of reliable communication in nation-building, and set the stage for the establishment of the United States Postal Service as we know it today.

After his diplomatic service in France, Franklin continued his scientific inquiries and public service, further cementing his legacy as one of the United States’ founding fathers.

Franklin’s scientific interests continued throughout his life. One notable contribution to the understanding of the natural world was his work on mapping the Gulf Stream, a major warm-water Atlantic Ocean current. This in fact began while serving as the joint Postmaster General for the British Crown prior to the American Revolution, and later as the Postmaster General for the United Colonies.

The background to this discovery ties Franklin’s ongoing interest in science with his practical responsibilities as Postmaster General. He was responsible for the timely and efficient delivery of mail, and this included mail between the colonies and Europe. Franklin noticed that American ships seemed to take longer to deliver mail to England than British ships took to deliver mail to America. Being the problem solver that he was, he started investigating why this was happening.

His cousin, Timothy Folger, was a Nantucket sea captain, and he provided a key piece of the puzzle. Folger explained that experienced American sea captains were aware of a strong, warm current off the East Coast of America that flowed northeastwards. Instead of fighting this current on their way to England, they would avoid it to save time. On the other hand, British mail ships, whose captains were less familiar with the local waters, would sail in the current, significantly lengthening their journey.

Franklin understood the significance of these observations. Collaborating with Folger, he created a chart of the Gulf Stream in 1770, providing visual evidence of its path. The map was distributed to ship captains with the instructions to use it to avoid the current when sailing eastwards to Europe.

However, it’s worth noting that while Franklin’s work on the Gulf Stream had significant scientific implications, it wasn’t until his later tenure as Postmaster General of the United Colonies that his findings were truly put to the test. The exigencies of war and the importance of transatlantic communication during the Revolutionary War meant that understanding and navigating the Gulf Stream became strategically crucial.

Franklin’s Gulf Stream chart was initially largely ignored or dismissed by British sea captains. Still, it gradually gained recognition and acceptance, and his work remains a testament to the application of scientific knowledge for practical problem-solving. His discoveries in mapping the Gulf Stream marked a significant contribution to oceanography and yet another instance of Franklin’s polymathic genius. Benjamin Franklin applied his understanding of science, even as Postmaster-General to the task of delivering the transatlantic mail!