(source)

(source)

|

John Gorrie

(3 Oct 1803 - 16 Jun 1855)

American physician who invented air-conditioning to cool the rooms of his malarial patients in Florida.

|

Apalachicola Birthplace of Mechanical Refrigeration

from Popular Mechanics (1958)

[p.122] This is the story of a man and ideas that were to change the way of life for large proportion of the world's population. Not one person in thousands has ever heard the man's name. He was Dr. John Gorrie, and his idea was artificial refrigeration.

Turn back the calendar more than 100 years. The place is Apalachicola, a quiet fishing town on Florida western Gulf Coast – a new, picturesque subtropical land beset by yellow fever and malaria. Here John Gorrie arrived in 1833. He had graduated from the College of physicians and surgeons in New York and had practiced medicine for six years at Abbeville, S.C. There he became interested in malaria and, in 1833 accepted a commission as medical officer in charge of the US Marine hospital at Apalachicola.

Within a year or two he was the postmaster, member of the city Council, treasurer of the city and territorial administrator, later director in two banks and part-owner of the Mason House, then the largest hostelry in the Territory of Florida. Just when he found time to practice medicine and to experiment with mechanical refrigeration is a mystery. The refrigeration experiments actually were a by-product of another scheme. In the treatment of fever Dr. Gorrie belief that if the patient's temperature could be artificially lowered, the disease would be cured.

With this in mind he attempted to air-condition one room in his home by passing a current of air over blocks of ice. This helped, but Dr. Gorrie was not satisfied. Besides, the only ice available was shipped from New England by water and cost over a dollar a pound.

His mind turned to other possibilities. Could he obtain cold by chemical or mechanical means? About 1755 William Cullen delivered a lecture in England on “cold produced by evaporating fluids, and of some other means of producing cold.” John Vallance received the first English patent for the production of cold in 1824. These proposed methods depended on it evaporation of fluids, but none of them was practical.

Dr. John Gorrie conducted most of his experiment secretly because it was a [p.123] common belief that mere man should not tamper too much with what God had created. Only God had ever created ice; it was thought improper for man to attempt it.

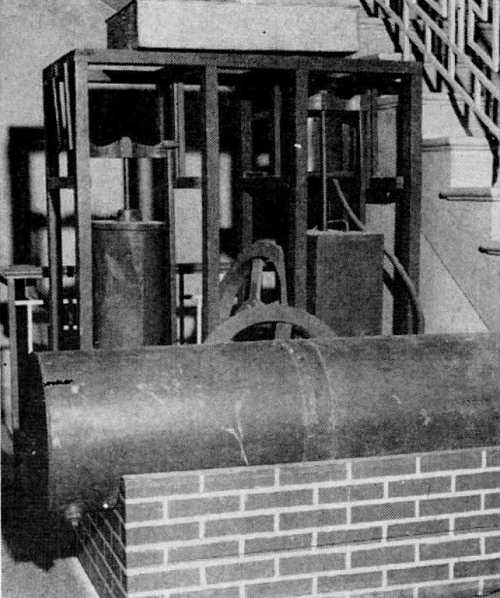

The machine Gorrie eventually came up with depended on compression, which required energy, and then the expansion of this air, which absorbed energy or heat. The driving power for his cumbersome machine was a wood-burning steam engine; the original is now in the Smithsonian Institution at Washington, D. C., and there is a replica in the Apalachicola Courthouse.

With this extremely unwieldy machine Dr. Gorrie satisfactorily cooled two rooms for his feverish patients. This was the birth of mechanical air-conditioning.

The machine had been in successful operation several years when about 1844, Dr. Gorrie had four patients critically ill. To alleviate their fevers the air-cooling machine operated at full speed over a long period when, one morning, it choked up and stopped. Investigation disclosed that the machine had iced up. Dr. Gorrie was quick to realize the import of the accident, and within a year or two he perfected a small machine that would produce ice in 8 by 10-inch blocks.

About this time the ladies of the local Trinity Episcopal Church decided to stage an ice-cream festival as the fund-raising project. Making the ice cream depended, of course, on the adequate supply of ice, scheduled to arrive by ship. Dawn of the festival day arrived, and no sail appeared on the horizon. The festival appeared to be off and the ladies were broken-hearted. Then Dr. Gorrie showed up with a load of sardine cans containing ice. The chief difficulty confronting the astounded and delighted ladies was how to get the precious ice out of the cans!

From here on the story of Dr. John Gorrie follows the typical theme of the early inventor. There were attempts to raise financial backing for his icemaking machine, but they always petered out despite the fact that patents were issued. Most discouraging was the attitude of the public: one Northern editor wrote: “A crank... In Apalachicola, Fla., claims he can make ice as good as Almighty God!”

Due largely to his difficulty marketing the icemaking machine Dr. Gorrie's finances went from bad to worse. On June 16, 1885, he died at Apalachicola, literally a victim of his cold-machine that was to affect the lives of so many people.

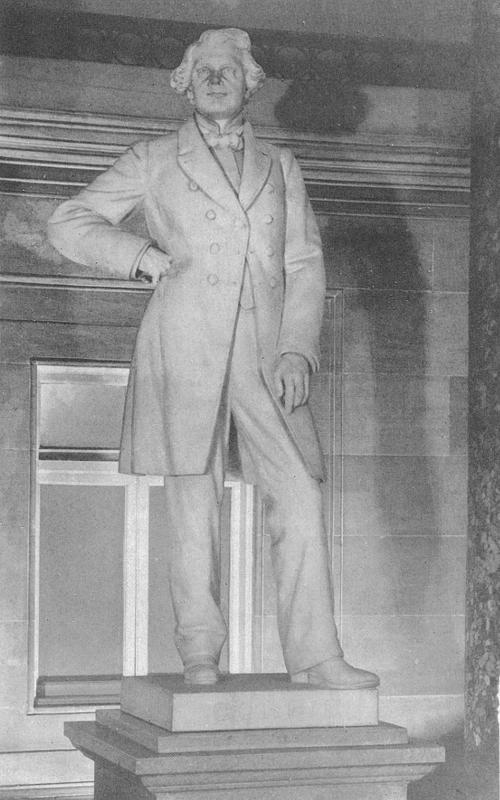

Recognition came late. In 1914 his statue was placed in statuary Hall at Washington, D.C., and in 1957 the state of Florida erected a memorial building to house the mementos of his life.

- Science Quotes by John Gorrie.

- 3 Oct - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Gorrie's birth.

- Fever Man: A Biography of Dr. John Gorrie, by V.M. Sherlock. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for John Gorrie.