(source)

(source)

|

Henry B. Hersey

(28 Jul 1861 - 26 Sep 1948)

American meteorologist and balloonist who was co-pilot of the balloon United States when it won the first international balloon race.

|

EXPERIENCES IN THE SKY

BY HENRY B. HERSEY

Inspector, United States Weather Bureau

from Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (1908)

[p.643] The skilful aëronaut who describes his remarkable experiences in the following pages has also faced danger on land and sea. During the Spanish War he served as Major in Roosevelt’s Rough-Riders, and in 1906-07 he was executive officer of the Wellman Polar Expedition. His sky journeys as a member of the aëro clubs of both France and America have been greatly facilitated by his practical knowledge of atmospheric temperatures and currents largely gained through his connection with the United States Weather Bureau.—The Editor.

FLOATING softly up into the blue ocean of air, watching the earth sink slowly away beneath us and fade and change quietly to an immense map spread before our wondering eyes—such are the first impressions of balloon voyagers. The noisy shouts of those who come to wish us “Bon voyage!” become fainter and fainter until absolute quiet reigns about us. It is so still that the ticking of the clock in the barograph is heard noisily counting the seconds as it traces the line of our upward flight across the sheet.

Meanwhile the earth-map down below us stretches out larger and larger; but its details are fading and becoming blurred. High hills have changed to flat surfaces. A river winds and bends its way through the duller colors like a tangled ribbon of silver. A small lake sparkles in the sunshine, giving life and fire to the sober shades about it. A railway train creeps slowly along, its trail of smoke streaming back over it; but as we look, it suddenly disappears from sight, apparently swallowed up before our eyes. Then we realize that it has plunged into a tunnel, through a hill which to us seems only a flat surface; now it appears again, coming out on the other side.

So the wonderful scenes come and go, ever changing, but ever grand and inspiring—scenes that come back to us real and vivid, that we may live them over again in later days. The cloud effects are at times the most beautiful of all. After having sailed up through these into the dazzling sunlight, we see the snowy billows just below our car, the shadow of our balloon falling upon their white surface. This shadow is often surrounded by a halo of rainbow colors of rare [p.644] beauty. At such times one has the feeling of having left the earth completely, and to have reached some other planet. The white masses just below seem to be quite solid, and look as though one might step out of the balloon and take a stroll over them, if one only had snow-shoes. The air is wonderfully clear and pure, and gives one a feeling of exhilaration much greater than that enjoyed in mountain-climbing. Is it, then, surprising that ballooning is rapidly becoming a popular sport?

In America ballooning is in its infancy, but in France almost any pleasant day in the year there are several balloon ascensions. There is certainly no recreation more absorbing, or which will make a man forget his business cares and troubles to a greater degree than this. Nor can there be one more healthful, since the devotee is carried quickly to an atmosphere free from dust and germs, where he must drink in long, deep breaths of the purest air.

In Europe there are many clubs which have balloon houses arranged for the quick inflation of balloons and for proper storage of them between flights. A club member may telephone the manager to “have Balloon Number Six ready for ascension at three o’clock this afternoon.” At the appointed hour he and his companions go to the club-house, where all is ready for a sail through the sky. On landing, the balloon is shipped back to the club, and the aëro party returns by train. Although we have several good aëro clubs in America,—notably at New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Boston,— they have not, so far, succeeded in making suitable arrangements for the convenient inflation of balloons. This will probably be done in the near future.

Of course no fire of any kind can be used in a balloon, and for flights lasting overnight the lack of a hot lunch is a cause for complaint; but this lack is now remedied by the use of thermal bottles, which provide hot coffee or bouillon for from twenty-four to thirty-six hours. I first used this resource in the race from Paris in 1906, when I assisted Lieutenant Lahm. The coffee was put in bottles about eleven o’clock in the forenoon before starting, and the next morning, in passing over England, we had a cup of coffee that was as hot as we could drink it. I used these bottles to good advantage in the St. Louis race; and on this trip we also had canned soups put up in a special double-can, with a filling of lime between the two cans. By pouring a little water into this lime, sufficient heat was generated to warm the soup in the inner can. These arrangements covered the food question satisfactorily; but the sky-voyager who is dependent on tobacco does not fare so well, since cigars and matches are contraband articles.

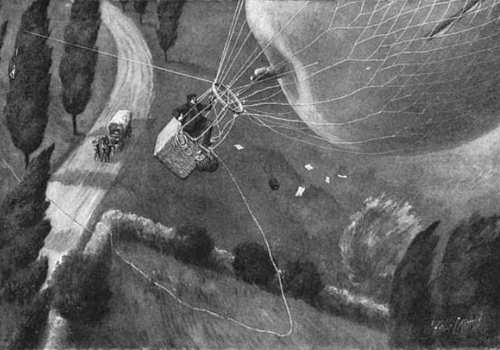

Drawn by Arthur T. Merrick

The pilot of a balloon does not have as good an opportunity as the passengers to enjoy the beautiful sights. He must watch carefully the barograph, which records automatically the height of the balloon above the earth, and the statoscope, which shows whether the balloon is ascending or descending; for, strange to say, one cannot tell by looking over whether the balloon is rising or falling. There is absolutely no sense of motion in either a horizontal or a vertical direction. To cause the balloon to rise it is necessary to throw out ballast, and to make it descend the gas is let out through a valve in the top. The pilot must know just how much ballast to throw out, and must decide when it is necessary to let out gas. These matters require constant attention, and the pilot is usually a busy man.

In a partly cloudy day it is very difficult to maintain the equilibrium of the balloon. The rays of the sun pass through its semi-transparent skin, sometimes raising the temperature of the gas to a point thirty or forty degrees higher than that of the surrounding air, in exactly the same way that the air in a hothouse is heated by the rays of the sun passing through its glass roof. Now, the heated gas has much greater lifting power, and the balloon climbs higher. If a cloud comes over the sun, the gas in the balloon cools rapidly, losing some of its ascensional force, and the balloon begins to descend. This must be checked by throwing out ballast; but good judgment must be exercised to prevent throwing out too much. Here is where the skill of the pilot is thoroughly tested. It is much easier to manage a balloon at night, as the effect of the sun on the gas does not have to be overcome, and frequently a balloon will sail through a whole night [p.645] at a steady height with almost no loss of ballast.

In the St. Louis race, after getting our equilibrium for the night about 8 p.m., we used less than one sack of ballast up to sunrise the next morning, and our height above the ground was virtually steady at a little more than 300 feet. The guide-rope which swung down about 300 feet below the basket occasionally touched the tree-tops. The guide-rope, as it is called, is simply a piece of rope suspended from the balloon, and is of great assistance in keeping the balloon steady when near the ground. If it descends until the end of the rope drags on the ground, the weight of the rope that is on the ground is taken off the balloon, and this will check its descent. It is also valuable in a dense fog, giving warning that one is nearing the earth.

Drawn by Harry Grant Dart. Engraved by C.W. Chadwick.

One of the chief difficulties met with by amateur balloonists is in making a good landing, especially in a strong wind. When the wind is light, it is comparatively simple; but if the balloon is flying along at the rate of forty miles an hour, which is not unusual, to bring it to a sudden stop in a country where there are trees, rocks, or buildings, requires good judgment and a cool head to avoid at least a lively shaking-up. Even after the basket strikes the ground, the huge gas-bag is still in the air, presenting a large surface to the wind. Unless it can be deflated almost instantly, the basket will probably be dragged swiftly along, even with the anchor out. If the anchor can be thrown into trees, it will usually hold, but on the ground it is apt to drag without catching. For quick deflation, an excellent device called the “ripping-cord,” or panel, has been introduced. From near the top of the balloon down to the equator a gash is cut. The sides of this cut are hemmed, and made strong with two thicknesses of cloth. A long patch or panel is then cemented over this cut, closing it and making it gas-tight. This panel terminates in a loop at the upper end, and to this loop is attached a cord, running down inside the balloon to the car. A sharp pull on this cord will tear the patch off, opening the side of the balloon for nearly a quarter of its circumference. Through this opening the gas rushes out in a few seconds, and the balloon collapses on the ground.

In my sixth ascension, which I made entirely alone, going up from Rueil, near [p.646] Paris, I had to make a landing in a wind blowing about forty miles an hour. I threw out the anchor as I was coming to a country road, with trees on each side of it. The anchor caught and held well in one of the trees, but the wind was so violent that the balloon stood out almost horizontally, and thrashed up and down frightfully, throwing things out of the basket. I succeeded in getting hold of the ripping-cord, and peeled off the panel in a hurry. Almost instantly the balloon settled down to the ground, giving no more trouble. This was my first experience in the use of the ripping-cord. Since then I have used it frequently, and have come to look on it as one of the greatest safeguards in ballooning. Of course one must be sure not to pull this cord by mistake up at a great height. For this reason the ripping-cord is colored red, to distinguish it easily from the valve-cord which hangs near it. The part of the cord coming down into the basket is now usually made flat, like a tape, so that it can be distinguished by feeling at night, when it is too dark to see the color. At one time, when practising alone in a small balloon, I tried the experiment of pulling the ripping-cord when I was about 150 feet in the air. I certainly got the hardest jolt I ever had in landing. The basket struck the ground with a terrific shock, and I was considerably dazed, though uninjured.

I have usually been lucky in making landings, but I had a rather exciting experience on one trip last May in France. I had gone up from Paris, taking with me Dr. W. N. Fowler, surgeon of the Wellman Polar Expedition, who wished to learn how to manage a balloon. We had gone about forty miles from Paris, and our experience had been very pleasant. As our ballast was nearly all used up. we were letting the balloon come down from an altitude of about four thousand feet. It was rather open country, with occasional small tracts of woodland. We floated down over one of these little patches of timber not much more than a hundred yards across. There were three or four poplar-trees that stood high above all the others, and I did not notice that the top of one of these had been broken off, leaving a sharp point. Our balloon came down a little faster than we expected, and as our basket swung along a few feet from this tree, the gas-bag, extending out above us, struck on this sharp stub, driving right through the balloon and tearing an opening ten feet in length. Our netting became entangled in the tree, while the gas poured out quickly. This left us hanging sixty feet above the ground, with almost no gas in the balloon, which threatened to tear loose. There was only one thing to do, and that was to get out as quickly as possible. The Doctor climbed out on the tree and descended to the ground. I then threw from the basket all the ballast and other loose material, and getting on the tree, climbed up to where the netting was caught, and succeeded in disentangling it, letting the balloon and the basket drop to the ground. The peasants had gathered round by this time, and cheerfully took hold and assisted us to get the balloon out and pack it up for shipment.

Free balloons, while in the air, have been considered to be safe from lightning; but last summer in Italy an aeronaut made an ascension at a big celebration, and was killed by lightning. The weather looked very threatening at the time, but as there was an enormous crowd, including the King and Queen of Italy, waiting to see the event, the aeronaut decided to start. He had gone only a short distance, and was being watched by the vast throng, when a flash of lightning struck the balloon, exploding the gas and killing the occupant instantly. This is said to be the only case on record of a free balloon being struck by lightning.

The pilot was Mr. F.H. Lahm (father of Lieutenant Lahm who won the Paris race in 1906). It is the moment of letting go and Mr. Lahm stands ready to empty a bag of ballast in case the balloon should not rise rapidly enough to clear the trees.

In my first ascension we had a rather exciting experience with lightning. We had gone up from the Aëro Club Park at St.-Cloud, near Paris, about eleven o’clock in the forenoon. The weather looked a little bad when we started, and there was scarcely any wind. The balloon was not a large one, and there were three of us in the basket, so we were able to take but little ballast. We went up about three thousand feet, and drifted lazily away from the park, changing direction from time to time, but not making any headway. Finally, when over the Seine, in the suburbs of Paris, a huge black cloud came rolling toward us from the west. Our pilot did not like the looks of it, [p.648] and it certainly did have a terrifying aspect. We did not have ballast enough to throw out and so go above it, so we decided to go down. The pilot pulled the valve-cord, letting out a lot of gas, and we went sliding down the sky at the rate of a thousand feet a minute. Just as we got well started, a vivid flash of lightning cut through the inky blackness of the cloud near us, followed almost instantly by a deafening roar of thunder, and the rain and hail came down in torrents. We were dropping straight toward a good-sized island in the middle of the Seine. We hoped to make a landing on this; but when we got within a few hundred feet of the earth, a little breeze sprang up, carrying us away from the island into the middle of the river. Our guide-rope was in the water and it looked like a swim for us; but throwing out what little ballast we had left, we stopped descending about thirty feet from the water. Then rising a little, we swept up the bank, across a street, over some low housetops, and down into a back yard, where we succeeded in making a fairly good landing. We were soon surrounded by an excited but good-natured Parisian crowd, anxious to help us. It was really a very busy few minutes; and as it was my first ascension, it was quite impressive to me. If we had been carrying plenty of ballast, we could have gone above the cloud, and then have come down later, after the storm had passed.

[p. 649] I am often asked about the dangers of ballooning. With a balloon of standard quality, properly constructed and handled by a skilful, conservative pilot, the danger is very slight if the ascension is not made near any large body of water. There is a very decided element of danger in going up too close to the sea-coast. Even if the surface wind is away from the water, a higher current may be in the opposite direction, and one may get into a fog or cloud and not be aware of a change of direction until the balloon is out over the sea, with no means of getting back. If it is daylight, there is of course a chance of rescue by some passing ship; but if it is night, there is but little hope. Two young English officers were drowned last summer in this way. They were seen drifting toward the sea just before dark. A day or two later one of the bodies and the wreckage from the balloon were washed up on the beach.

The Great Lakes of this country have claimed their share of tribute. Professor John Wise, an experienced aeronaut, made an ascension from St. Louis in 1879, and came down in the southern end of Lake Michigan, where he and his companion, George Burr, were both drowned. In 1875, the veteran aeronaut Professor Donaldson made an ascension from Chicago with a young newspaper reporter for a companion. They were never again seen alive, both being drowned in Lake Michigan. Water is the only serious danger the balloonist has to encounter, and this can be avoided. If an ascension is made near a large body of water,—that is, one too large to attempt to cross,—the balloon should be kept at a low altitude, so that a quick descent can be made if the pilot finds that he is drifting dangerously close. If this is done, no great risk will be incurred.

All balloons taking up passengers should be managed by experienced pilots. This is a matter which has generally been insisted on by the various aëro clubs, and licenses are issued by them to competent persons who have fulfilled certain requirements. They must have made not less than ten ascensions. Of these, two must have been under the supervision of [p.650] a licensed pilot, at least one must have been made entirely alone, and one must have been a night ascension. The applicant must also be recommended by two licensed pilots who are familiar with his work. There are very few licensed pilots in this country at present, but a number are going through the preparatory work. In all races held under the auspices of the International Aeronautic Federation, one of the requirements is that the balloons must be handled by licensed pilots.

It has been my good fortune to take part in two international races. In 1906 I accompanied Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm in the “United States” in the race for the Gordon Bennett cup. This opportunity came to me quite unexpectedly. I had just returned to Paris from the Arctic region, where I had been on duty with Mr. Walter Wellman’s expedition in preparing for an attempt to reach the North Pole by means of a dirigible balloon or air-ship. Lieutenant Lahm had engaged a French aeronaut to assist him, but this had aroused a storm of protest from the French contestants. Learning of this, I immediately offered my services to Lieutenant Lahm, and they were accepted, although it was only about an hour before starting that the matter was definitely settled.

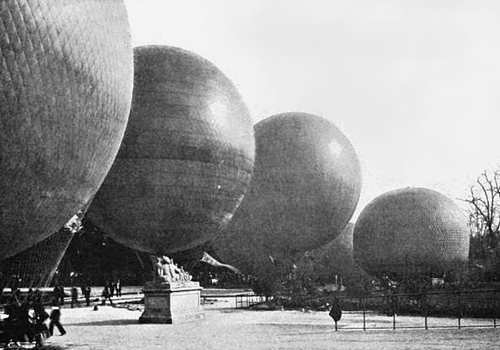

The experience in this race was very pleasant. The weather was perfect, and there was an enormous crowd out to see the start from the Jardin des Tuileries. There were sixteen balloons in the contest, representing France, England, Germany, Italy, Spain, and America, and the list of pilots included the names of the most famous aëronauts of the world. It had been expected that a westerly wind would prevail, carrying the air fleet over Germany, Austria, or Russia; but the wind was from the opposite direction, and we all sailed west, straight for the Atlantic. I had studied the French weather-chart pretty carefully, and believed that our course would change to northwest when we got out over western France, and give us a chance to cross the English Channel and reach the British Isles. We kept low out over France, and for the first fifty miles continued to travel straight west. A little later we began to veer slightly to the northwest. This was very encouraging, and we decided to go out over the Channel. As we neared the coast, we could see the flash of a lighthouse, and a little after 11 p.m. we floated out over the water. We still kept low, as we were getting a strong breeze and a good direction. At 2:30 a.m. we sighted the intermittent red-and-white flash of a light-ship stationed east of the Isle of Wight. Our course was now nearly northwest, and at 3:30 a.m. we sailed in over the English coast near Chichester, having covered a distance of 125 miles in a little less than four and a half hours. We continued a northerly course over England, and as the sun came up, heating the gas in our balloon, we began to rise slowly, finally reaching an altitude of about 10,000 feet. Our course now changed to east of north, and at 3 p.m. we found we were getting close to the North Sea. We decided to make a landing as near the coast as possible. The wind was blowing about twenty-five miles an hour, and we were kept pretty busy for a few minutes, but we succeeded in landing in a smooth field about half a mile from the shore.

We had been in the air more than twenty-two hours, and were 402 miles in a direct line from Paris. We landed on the estate of a gentleman of the name of Barry, who was extremely kind to us. His men helped us pack the balloon, and we left at 5 p.m. for London. We went only as far as York that night, for on arriving there, and finding we must wait some time for a train, we decided to go to the hotel and get some much needed sleep. In the morning we learned that we had won the cup. It turned out that nine of the sixteen balloons had dropped down in France, not thinking it wise to attempt to cross the Channel.

It was due to Lieutenant Lahm’s energy in preparing for and entering this race, and to his skilful handling of this balloon, that the race was held in this country, at St. Louis, in 1907. As he had won the cup, the American club which he represented had the right to say where the next contest would be held, and the management decided on St. Louis. This proved to be a wise decision. The St. Louis people took hold of the work of preparation in an energetic manner. An unusually good quality of coal-gas was secured, and the whole work of [p.651] inflating and starting the balloons in the race was most efficiently done. It must be remembered that this was the first balloon-race ever held in America, yet everything was managed smoothly and efficiently. The Aëro Club of America and the St. Louis people certainly deserve great credit for their excellent showing.

The work of the weather bureau in connection with this event is worthy of mention. Copies of the daily weather-map were placed at the disposal of the contestants every morning by the St. Louis office, and on the day of the race, under instructions from Professor Willis L. Moore, chief of the bureau, special observations were made at noon in all parts of the country. These reports were telegraphed to the St. Louis office, and a special map was issued, showing the weather conditions existing at the time over the whole country. No other weather service in the world could have done this, and it was looked upon by the foreign contestants as a wonderful achievement.

These are a few of the balloons which started in the Paris race of 1906, but the picture does not include the winner, the “United States,” which was piloted by Lieutenant Lahm with Major Hersey as assistant.

I entered the St. Louis race very unexpectedly. During the preceding summer I had again been in the Arctic with Mr. Wellman, and on getting back to Norway, in September, I found a letter from Lieutenant Lahm, in which he stated that [p.652] he had entered the race, and had designated me as his alternate and asked me to assist him again. I immediately wired him that I should be glad to accept; but when I arrived in London, I found a letter from him saying that his recovery from a severe attack of typhoid fever had been so slow that he would not be able to take part in the race, and urging me to be sure to take his place.

I hurried across the Atlantic to make the necessary preparations, as the time was getting short. It was difficult to get an aide who had done any ballooning. There were plenty of applications from good men, but most of them had never been in a balloon. There was one application from a St. Louis girl, a very clever young newspaper writer. She could hardly be induced to take “No” for an answer, and I believe she would have been a really good assistant. I decided on Mr. Arthur T. Atherholt of Philadelphia. He had made only three ascensions, but had shown decided ability in the work he had done in these. I had no reason to regret my decision, as he proved to be not only a good assistant, but a very pleasant companion.

We went up in the “United States” from St. Louis at 4:05 p.m. Starting in a northwesterly direction, we soon crossed the Missouri River and a little later the Mississippi, near the mouth of the Illinois River. A small motorboat was puffing saucily down the river in the faint light of the rising moon. We were less than 400 feet above the river, and we shouted down to them and learned just where we were. Our course now changed to about north, and we continued sailing along a little more than 300 feet above the earth. I had kept low in order to get as long a run to the north as possible, hoping to be able to reach the Atlantic coast as far north as New England the next night. The higher currents would have carried us east sooner, but they would have brought us to the Atlantic coast farther south.

All night long we floated silently through the moonlight at an even altitude. Mr. Atherholt, who had a rich tenor voice, sang several charming songs, and occasionally we had a shouted conversation with people as we passed over towns. We had recognized, in passing, several of the larger towns, including [p.653] Macomb and Galesburg, Illinois, and our course had gradually turned to the northeast. Just before sunrise we came sweeping down to Lake Michigan, and passed directly over Zion City of Dowie fame, about forty miles north of Chicago, and out over Lake Michigan. One solitary steamer was running down the west shore, and this was the only craft of any kind that we saw on the lake.

As the sun struck the balloon we began to climb steadily, and had attained an altitude of about 4500 feet when we reached the Michigan shore. We were now traveling about forty miles an hour in an easterly direction across the State of Michigan. At 1:20 p.m. we reached Lake St. Clair, with Detroit in full view to the south of us. Intermittent cloud and sunshine had made it necessary to throw over considerable ballast. We passed straight across Lake St. Clair, reaching Lake Erie near Rondeau, Canada. We sailed out over Lake Erie, expecting to reach the New York shore south of Buffalo, but when we were out in the middle of the lake the wind changed, carrying us northeast into Canada again. This brought us up to the west end of Lake Ontario, with a direction which would take us the whole length of the lake, a distance of nearly 200 miles. As we had less than eight sacks of ballast left, we felt that it would not be wise to attempt this at a time of day when the balloon, due to the increasing coldness of the night, was losing its buoyancy.

We decided to make a landing, but as it was now getting dark and the country was very rough, it was not easy to do this in the heavy wind that was blowing. We finally succeeded in dropping down into a plowed field, and made a very gentle landing by use of the ripping-cord. Mr. Thomas Berry, a farmer living near by, kindly invited us to supper, which was all ready, and we enjoyed a delicious meal, after which, Mr. Berry hitched up his horse and drove us into Caledonia, the nearest town, a distance of seven miles. We had been in the air twenty-five hours and ten minutes, and had made a distance of 625 miles in a direct line from St. Louis, but had actually covered 750 miles or more, about 175 miles of which distance was over water.

Our balloon should have been [p.654] revarnished, but I did not have time before the race. If this had been done it would have held gas much better, and we would probably have been able to cross Lake Ontario and make a much better showing.

I had chosen the low current the first night because it carried us to the north. I wished to get well in the north so that when we went east we would have a chance for a long flight out over New England or possibly New Brunswick, but the condition of my balloon defeated this plan.

The winner of the race, Mr. Erbsloh in the German balloon “Pommern,” and the close second Mr. Le Blanc in the French balloon “Islede France,” had balloons that were in perfect condition, and they are both excellent aëronauts.

I believe that if Mr. Erbsloh had gotten as far north as we did that he would have been able to go east to the New Brunswick coast, not only winning the cup but breaking the world’s record for long distance.

Much discussion is heard in regard to the future of ballooning and aerial navigation of all kinds. The spherical balloon, which is the simplest form of aircraft, can never be used to any great extent except for pleasure. It affords a delightful, quiet ride through the air, but no absolute point of landing can be determined on in advance, and this precludes its use in a business way to any great extent. The aëroplane or flying-machine, using no gas, but lifting itself into the air by its own power, is now being worked out all over the world by many ingenious minds. While a few short flights have been made, it is still far from being an established success. It is probable that an immense amount of experimental work, occupying a number of years, will be necessary before this means of air travel will become practicable. Indeed, I do not believe that any form of aërial locomotion will ever be able to compete in a commercial way with the present means of transportation.

The dirigible balloon, or air-ship, as it is usually called, is now an established success, and is sure to play an important part in future wars. The French government is taking the lead in the matter, and will soon have a whole fleet of aërial cruisers, capable of sailing over the enemy’s defenses and dropping hundreds of pounds of dynamite into their fortifications; or of gliding quietly out at night over a battle-ship, and dropping down on [p.655] her enough dynamite to send her, a shattered wreck, with all on board, to the bottom of the sea.

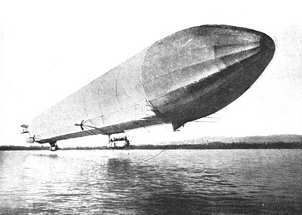

From a photograph by E. Frankl, Berlin

Germany is also making rapid strides in this work. Count Zeppelin, working under the patronage of the government, has built the largest and probably the most scientifically planned air-ship ever constructed. This ship, named the ———, is more than 400 feet in length, and has made a speed of thirty-five miles an hour in calm weather. Instead of one large gas-bag, it has an aluminum frame holding a dozen smaller gas envelops. In this way greater rigidity is secured, and one gas compartment may be pierced by cannon-shots without injury to the others. England is now working hard to keep pace with the advances in this feature of warfare, and has an air cruiser which has done good work. Italy, Spain, and all the European nations, in fact, are working at the problem.

Italy is paying great attention to the employment of the balloon for photographing and it is said that a branch of the military service has thus photographed the whole of the northern frontier, as well as a large part of the interior. Some of the pictures of Rome herewith presented are particularly interesting.

Our own government has done but little in ballooning except in the way of preparatory work. An aëronautic division has been organized in the signal corps, and a small body of picked men is being trained in aëronautics by use of the ordinary spherical balloon.

While we feel secure from war in our isolated position, and with our enormous resources, yet we should at all times be prepared, and no important advance in the art of war like the use of air cruisers should be neglected. We are a peaceful nation, but the very fact of our being fully prepared is the greatest safeguard against aggression which might involve us in war.

- 28 Jul - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Hersey's birth.