(source)

(source)

|

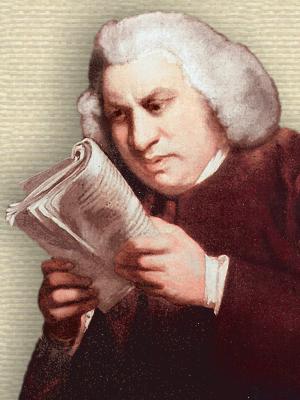

Samuel Johnson

(18 Sep 1709 - 13 Dec 1784)

English essayist whose enormous literary output included the first great critique of Shakespeare (1765), and his Dictionary of the English Language (1755). From the scope of his work, he has been various described as poet, dramatist, journalist, satirist, biographer, essayist, lexicographer, editor, translator, critic, parliamentary reporter, political writer, story writer, sermon writer, travel writer and social anthropologist, prose stylist and conversationalist. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, near the memorial to Shakespeare.

|

The Rambler

by Samuel Johnson

No. 83. Tuesday, Jan. 1, 1750.

All useless science is an empty boast.

[Samuel Johnson contrasts the seeking of mere curiosities of science (“toys and trinkets”), with collecting to be useful for learning. He admires the true intellectual invention of Isaac Newton.]

[p.149] THE publication of the letter in my last paper has naturally led me to the consideration of thirst after curiosities, which often draws contempt and ridicule upon itself, but which is perhaps no otherwise blameable, than as it wants those circumstantial recommendations which add lustre [p.150] even to moral excellencies, and are absolutely necessary to the grace and beauty of indifferent actions.

Learning confers so much superiority on those who possess it, that they might probably have escaped all censure had they been able to agree among themselves; but as envy and competition have divided the republick of letters into factions, they have neglected the common interest; each has called in foreign aid, and endeavoured to strengthen his own cause by the frown of power, the hiss of ignorance, and the clamour of popularity. They have all engaged in feuds, till by mutual hostilities they demolished those out-works which veneration had raised for their security, and exposed themselves to barbarians, by whom every region of science is equally laid waste.

Between men of different studies and professions, may be observed a constant reciprocation of reproaches. The collector of shells and stones derides the folly of him who pastes leaves and flowers upon paper, pleases himself with colours that are perceptibly fading, and amasses with care what cannot be preserved. The hunter of insects stands amazed that any man can waste his short time upon lifeless matter, while many tribes of animals yet want their history. Every one is inclined not only to promote his own study, but to exclude all others from regard, and having heated his imagination with some favourite pursuit, wonders that the rest of mankind are not seized with the same passion.

There are, indeed, many subjects of study which seem but remotely allied to useful knowledge, and of little importance to happiness or virtue; nor is it easy to forbear some sallies of merriment, or expressions of pity, when we see a man wrinkled with attention, and emaciated with solicitude, in the investigation of questions, of which, without visible [p.151] inconvenience, the world may expire in ignorance. Yet it is dangerous to discourage well-intended labours, or innocent curiosity; for he who is employed in searches, which by any deduction of consequences tend to the benefit of life, is surely laudable, in comparison of those who spend their time in counteracting happiness, and filling the world with wrong and danger, confusion and remorse. No man can perform so little as not to have reason to congratulate himself on his merits, when he beholds the multitudes that live in total idleness, and have never yet endeavoured to be useful.

It is impossible to determine the limits of inquiry, or to foresee what consequences a new discovery may produce. He who suffers not his faculties to lie torpid, has a chance, whatever be his employment, of doing good to his fellow creatures. The man that first ranged the woods in search of medicinal springs, or climbed the mountains for salutary plants, has undoubtedly merited the gratitude of posterity, how much soever his frequent miscarriages might excite the scorn of his contemporaries. If what appears little be universally despised, nothing greater can be attained, for all that is great was at first little, and rose to its present bulk by gradual accessions, and accumulated labours.

Those who lay out time or money in assembling matter for contemplation, are doubtless entitled to some degree of respect, though in a flight of gaiety it be easy to ridicule their treasure, or in a fit of sullenness to despise it. A man who thinks only on the particular object before him, goes not away much illuminated by having enjoyed the privilege of handling the tooth of a shark, or the paw of a white bear; yet there is nothing more worthy of admiration to a philosophical eye than the structure of animals, by which they are qualified to support life in the elements or climates to which they are [p.152] appropriated; and of all natural bodies it must be generally confessed, that they exhibit evidences of infinite wisdom, bear their testimony to the supreme reason, and excite in the mind new raptures of gratitude, and new incentives to piety.

To collect the productions of art, and examples of mechanical science or manual ability, is unquestionably useful, even when the things themselves are of small importance, because it is always advantageous to know how far the human powers have proceeded, and how much experience has found to be within the reach of diligence. Idleness and timidity often despair without being overcome, and forbear attempts for fear of being defeated; and we may promote the invigoration of faint endeavours, by shewing what has been already performed. It may sometimes happen that the greatest efforts of ingenuity have been exerted in trifles; yet the same principles and expedients may be applied to more valuable purposes, and the movements, which put into action machines of no use but to raise the wonder of ignorance, may be employed to drain fens, or manufacture metals, to assist the architect, or preserve the sailor.

For the utensils, arms, or dresses of foreign nations, which make the greatest part of many collections, I have little regard when they are valued only because they are foreign, and can suggest no improvement of our own practice. Yet they are not all equally useless, nor can it be always safely determined which should be rejected or retained; for they may sometimes unexpectedly contribute to the illustration of history, and to the knowledge of the natural commodities of the country, or of the genius and customs of its inhabitants.

Oil on shaped canvas, 99 × 137 cm (source)

Rarities there are of yet a lower rank, which owe their worth merely to accident, and which can [p.153] convey no information, nor satisfy any rational desire. Such are many fragments of antiquity, as urns and pieces of pavement; and things held in veneration only for having been once the property of some eminent person, as the armour of King Henry, or for having been used on some remarkable occasion, as the lantern of Guy Faux2. The loss or preservation of these seems to be a thing indifferent, nor can I perceive why the possession of them should be coveted. Yet, perhaps, even this curiosity is implanted by nature; and when I find Tully confessing of himself, that he could not forbear at Athens to visit the walks and houses which the old philosophers had frequented or inhabited, and recollect the reverence which every nation, civil and barbarous, has paid to the ground where merit has been buried, I am afraid to declare against the general voice of mankind, and am inclined to believe, that this regard, which we involuntarily pay to the meanest relique of a man great and illustrious, is intended as an incitement to labour, and an encouragement to expect the same renown, if it be sought by the same virtues.

The virtuoso therefore cannot be said to be wholly useless; but perhaps he may be sometimes culpable for confining himself to business below his genius, and losing, in petty speculations, those hours by which, if he had spent them in nobler studies, he might have given new light to the intellectual world. It is never without grief, that I find a man capable of ratiocination or invention enlisting himself in this secondary class of learning; for when he has once discovered a method of gratifying his desire of eminence by expense rather than by labour, and known the sweets of a life blest at once with the ease of idleness, and the reputation of knowledge, he will not easily be brought to undergo again the toil of thinking, or leave his toys and trinkets for arguments and principles, arguments which require [p.154] circumspection and vigilance, and principles which cannot be obtained but by the drudgery of meditation. He will gladly shut himself up for ever with his shells and medals, like the companions of Ulysses, who, having tasted the fruit of Lotos, would not, even by the hope of seeing their own country, be tempted again to the dangers of the sea.

Insatiate riots in the sweet repasts;

Nor other home nor other care intends,

But quits his house, his country, and his friends. Pope3.

Collections of this kind are of use to the learned, as heaps of stones and piles of timber are necessary to the architect. But to dig the quarry or to search the field, requires not much of any quality beyond stubborn perseverance; and though genius must often lie unactive without this humble assistance, yet this can claim little praise, because every man can afford it.

To mean understandings, it is sufficient honour to be numbered amongst the lowest labourers of learning; but different abilities must find different tasks. To hew stone, would have been unworthy of Palladio; and to have rambled in search of shells and flowers, had but ill suited with the capacity of Newton.

2 The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, has the lantern said to have been carried by Guy Fawkes when arrested in the cellars of the Houses of Parliament upon discovery of the Gunpowder Plot (5 Nov 1605).

3 Verse from Pope’s translation of the Odyssey by Homer.

4 Andrea Palladio was an Italian architect regarded by man to be the most influential in the history of Western architecture.

- Science Quotes by Samuel Johnson.