(source)

(source)

|

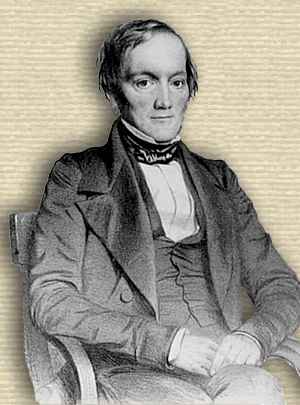

Sir Richard Owen

(20 Jul 1804 - 18 Dec 1892)

English zoologist, anatomist and palaeontologist who made reconstructions of many prehistoric animals and birds, coined the word dinosaur, and was responsible for establishing South Kensington building for the British Natural History Museum.

|

OWEN

1804–1892

from Biographies of Scientific Men (1912)

by Arthur Bowen Griffths1

[p.75] “DOCTI non solum vivi atque præsentes studiosus dicendi erudiunt, atque docent; sed hoc etiam post mortem monimentis literarum assequuntur,” wrote Cicero2 nearly two thousand years ago, and it is very true of Owen and others mentioned in the present volume.

At the time when Napoleon’s invasion of England was completely organized, and only to be overthrown by the power of Nelson, there was born at Lancaster, on 20th July 1804, Richard Owen, destined to be the greatest comparative anatomist and palæontologist of the nineteenth century. Although an Englishman on his father’s side, Owen’s mother was of French extraction, belonging to a Huguenot family named Parrin, and at the age of six he went to the Lancaster Grammar School, but showed no signs during his schooldays of the bent of his future career. At the age of sixteen he was apprenticed to a surgeon and apothecary, and in 1824 proceeded to the Edinburgh University to study medicine; but the following year he came to London, where he joined the medical [p.76] school of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. During these days he was prosector to Abernethy, and in 1826 he obtained the Diploma of the Royal College of Surgeons. Having completed his medical studies, he began to practise as a medical man at 11 Cook’s Court, Lincoln’s Inn Fields; but from the beginning of his career he was much more interested in scientific pursuits than in strictly professional duties. In 1828, at the age of twenty-four, and knowing his great skill as a dissector, Owen was, at the suggestion of Abernethy, invited to act as assistant curator of the Hunterian collection in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, of which Mr William Clift was curator; and in the same year he was appointed lecturer on comparative anatomy at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. His duties at the Royal College were to catalogue the great collection of Hunter, whose manuscript had been lost. The collection meant the examination and description of no less than 3970 specimens. He was equal in every respect to this great task, as his subsequent genius proved.

In 1830 Cuvier visited England, and Owen made his personal acquaintance, and the following year visited Paris. Cuvier at this time was busy on his great work on fishes, which made a great impression on Owen, so much so that he attributed his subsequent work on palæontology to “the debt which he owed to Cuvier.”

On 1st August 1831, during his visit to Paris, he went [p.77] to the Théâtre Français, but did not stay to the end of the performance, stating that “the statue of Voltaire in the salle was worth all the money.”

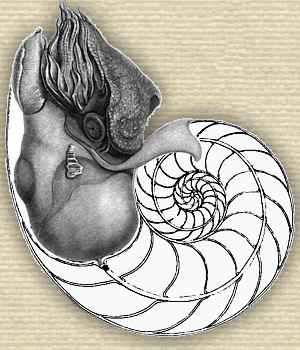

In 1832 Owen published his famous Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus, “which placed its author, at a bound, in the front rank of anatomical monographers,” says the late Professor Huxley. “There is nothing better in the Mémoires sur les Mollusques; I would even venture to say nothing so good; … certainly in the sixty years that have elapsed since the publication of this remarkable monograph, it has not been excelled.” The Pearly Nautilus (Nautilus pompilus) is interesting not only on its own account, but because of the large number of its fossil allies, and Owen won for himself an honourable place among naturalists by the masterly way in which he explained its structure and affinities. In his work he demonstrated for the first time the structure of the extinct group of cuttle-fishes to which the ammonites belonged, and to this his Memoir forms one of the classics of palæontology. It was translated into French by Milne Edwards, and into German by Oken.

Between 1831-34 Owen published thirty-seven papers, besides the catalogues of the Hunterian collection; these include papers on the anatomy and osteology of the orang-outang, beaver, suricate acouchy, Tibet bear, garmet, armadillo, seal, kangaroo, tapir, crocodile, stomapodous crustacea, ceropithecus, ariel toucan, flamingo, [p.78] hyrax, brachiopoda, cheetah, hornbill, lion, tiger, touraco, amphibia, etc.

In 1834 Owen was appointed Professor of Comparative Anatomy at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and elected F.R.S. On 20th July 1835, on the thirty-first anniversary of his birth, he married Caroline Clift, the daughter of the curator of the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons.

In 1836 he was appointed Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons, a position which he held for nineteen years. He also succeeded his father-in-law at the Royal College.

So much scientific work was entrusted to him that he had no time for practice as a medical man. Accordingly, he gradually withdrew from it, and devoted himself wholly to the labours in which he had already given evidence of an original and powerful genius. His industry was untiring, and in every publication he gave fresh proofs for penetrating insight and a capacity for far-reaching generalization.

Between 1833-40 he completed, in five volumes, the catalogue of the specimens in the Hunterian collection; and in 1853 appeared in two volumes the catalogue of the osteological specimens; in 1855, in three volumes, that of the fossil vertebrates and cephalopods. In 1840-45 he issued Odontography, a work in which he brought together a vast amount of observations on the structure of the teeth. Owen’s lectures at the Royal College were [p.79] published in book form in 1843 and in 1860-68—the former a volume on the invertebrata, and the latter, in three volumes, on the vertebrata; and in 1855 another series of lectures on the comparative anatomy and physiology of the invertebrate animals was published in book form, the volume occupying 689 pages of print, with 235 illustrations. In the concluding lecture Owen says:—

The invertebrated classes include the most numerous and diversified forms of the Animal Kingdom. At the very beginning of our inquiries into their vital powers and acts we are impressed with their important relations to the maintenance of life and organization on this planet, and their influence in purifying the sea and augmenting and enriching the land—relations of which the physiologist conversant only with the vertebrated animals must have remained ignorant.

These lectures were welcomed both in England and on the Continent; and in his work on the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton he made at the time a contribution of a high order to what may be termed the philosophy of natural history, showing how closely the bones, especially in the head, of vertebrate animals conform to a general type; but the ideas expressed in this work limited his vision. This was a misfortune, as his theory has been altered by the subsequent work of embryologists.

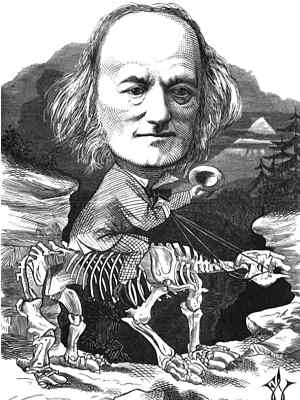

In his work on the Archetype he dissented from the philosophy of Cuvier, and was inclined to that of Oken and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. In matters of morphological speculation Owen passed from the school of Cuvier into [p.80] that of Cuvier’s adversaries; but in matters of comparative anatomy and of palæontology his place is next to his master Cuvier, the founder of these sciences. In fact, Owen has been called “the British Cuvier,” and lovingly by his friends “Old Bones,” on account of his vast knowledge of osteology; and concerning his book on The Anatomy and Physiology of the Vertebrates, the late Sir William Flower called it “the most encyclopædic work on the subject accomplished by any one individual since Cuvier’s Leçons d’Anatomie Compareé.”

Minute studies of the bones of living animals enabled Owen to reconstruct many extinct and fossil forms—in this respect following in the footsteps of Cuvier. He reconstructed the Dinornis from a fragment of its femur; asserting that it belonged to a gigantic wingless bird, and, moreover, that it was a marrow bone like that of a mammal, and not a pneumatic one like those of birds; and, later, the whole skeleton of this bird was brought from New Zealand, and was exactly like the outline drawn (from a single bone) by Owen.

In 1849-84 he published his great work, The History of British Fossil Reptiles, and in 1846 a similar one on British Fossil Mammalia and Birds. His memoirs on the gigantic sloth (Mylodon robustus) discovered near Buenos Ayres, on the giant birds of New Zealand, on the Archæopteryx macrura, the oldest known reptilian bird found in the Solenhofen stone of Bavaria, on the [p.81] extinct reptiles of Great Britain, on the fossil belemnites from the Oxford clay, on the wading land bird Gastornis Parisiensis, etc., remain well-known classics. In 1877 he published two volumes, Researches on the Fossil Remains of the Extinct Mammals of Australia, with a Notice of the Extinct Marsupials of England, and in 1879 two volumes on the Extinct Wingless Birds of New Zealand; and even as late as 1889 he published monographs on fossil Reptilia and Cetacea. At the age of eighty-five we find Owen at work on his favourite subjects. This certainly upsets Oslerism, or “too old at forty”! And it should be borne in mind that the greatest philosopher of the nineteenth century, Herbert Spencer, did not commence writing his volumes on the Synthetic Philosophy until the age of forty.

In addition to the previously-mentioned researches, by his numerous memoirs on Mesozoic land reptiles, to which he gave the name of Dinosaurs, and a hundred or more other pieces of work, Owen did inestimable service to palæontology.

Owen excelled Cuvier in the accuracy of his work and in the generalizing spirit which he brought to bear upon his problems. Erroneous in some of his theories; but where is the worker who has not made faults? As Liebig said, “The man who never made a fault never worked.”

The working out of the structural contrasts between [p.82] the Artiodactyl and Perissodactyl Ungulata is representative of the best morphological work; and Owen rendered the greatest service to morphology in 1843 by his clear definition of analogy and homology—the former being illustrated by “a part or organ in one animal which has the same function as another part or organ in a different animal”; the latter being illustrated by “the same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function,” i.e. organs of similar development and structure are homologous; organs of similar function are analogous. The further elaborations of homology, due to the doctrine of evolution, etc., have been worked out by Agassiz, Bronn, Haeckel, Mivart, Lankester, and others. Owen is the connecting-link between Cuvier and the present school of biologists. On the one hand, he was unappreciative of Darwinism, and on the other, “really believed in the derivation of species from one another.” He will always be remembered, as long as natural history exists, for his practical work in comparative anatomy and palæontology; but many of his philosophical ideas have been superseded by the work of modern biologists. It was unfortunate that Owen did not appreciate the work of Darwin and others. He was unable to accept the theory of the origin of species by natural selection, but his investigations did much to prepare the way for the general and rapid acceptance of Darwin’s theory, since it was felt that there must be some strictly scientific explanation of the affinities by which [p.83] he had shown vast groups of animals to be allied to one another.

Owen’s palæontological work is of the highest order; and in work like his fossil mammals, birds, and reptiles, he excelled. The most characteristic of his faculties was a powerful scientific imagination. As the author wrote in one of his books, “the imagination is, after all, the most precious faculty with which a scientist can be equipped. It is a risky possession, it is true, for it leads him astray a hundred times for once that it conducts him to truth; but without it he has no chance at all of getting at the meaning of the facts he has learned or discovered.”3 Professor H. E. Armstrong says: “It is justifiable to say that imagination plays an important part in chemistry; and that if too rigidly and narrowly interpreted, facts may become very misleading factors.”4

Fragments of bone which might be meaningless to less alert observers enabled Owen to divine the structure and present the images of whole groups of extinct animals—in this respect he was a disciple of Cuvier; and Cuvier was Owen’s model. Cuvier could not accept the doctrine of homology, or the likeness of corresponding organs in animals as regards structure and type, as, e.g., between the foreleg of a quadruped, the wing of a bird, and the arm of a man, which are of kindred origin, but modified through [p.84] long and lateral descent for the work which they do. The influence of Cuvier’s ideas on Owen was manifest through the career of the latter, arresting his development in certain directions. This is unfortunately shown in Owen’s attitude towards Darwinism; he did not accept the doctrine of the mutability of species, the common descent of every animal and plant from formless or seemingly structureless masses of matter which, through an infinite series of changes, have become modified into the teeming forms that have flourished or that now flourish on this planet, which was satirically termed by Voltaire “le meilleur des mondes possible.” But if Owen failed to appreciate the modern doctrine of evolution (he was fifty-five years old when Darwin’s Origin of Species was issued), he had published nearly four hundred monographs, books, etc., and, like Priestley in another science, could not conscientiously alter his views. His attitude caused bitter resentment in certain quarters. He made, however, solid and permanently valuable contributions to natural history, and his “monographic work occupies a unique position.”

His work on the anthropoid apes, on the Monotremes and Marsupials, on the Apteryx, the Great Auk and the Dodo, on Lepidosiren, on the Cephalopoda, on Limulus, on the Brachiopoda, and on Trichina spiralis, are all of the highest importance. Likewise his work on Darwin’s extinct mammal of South America, Toxodon Platensis, “referable by its dentition to the Rodentia, but with affinities to the Pachydermata and the herbivorous Cetacea”; and his other memoirs on the extinct fauna [p.85] of South America. As Huxley wrote: “I do not know where one is to look for contributions to palæontology more varied, more numerous, and, on the whole, more accurate, than those which Owen poured forth in rapid succession between 1837 and 1888.”

Owen remarks in his Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Invertebrate Animals, 1855, p. 639, that physiology is dependent on comparative anatomy, but the idea is not applicable at the present day, as physiology is dependent on chemistry and physics. In later life he knew this, and greatly appreciated the work of others, as the following letters to the author bear evidence:—

4th February 1885.—I feel much indebted to you for the communication of the acceptable and interesting discovery of the renal organs of Astacus; and for the opportunity of connecting my name therewith as humble introducer of your refined analytic research to the Royal Society.

31st March 1885.— … I shall receive with pleasure every research of yours.

18th May 1887.—I have read and studied your memoir “On the Nephridia and Liver of Patella vulgata” with instruction and gratification; the latter excited by the evidence of advance in the study of the functions of the organs of Molluscs as exemplified in the species selected. It cannot fail to excite similar applications of chemistry to the determination of function in other species as easily acquired for the purpose as the common limpet.

23rd May 1888.—Your valuable paper, “Further Researches on the Physiology of the Invertebrata,” herewith returned, I have read carefully and profitably, but with effort, due to failing vitality. I fear you must enter me a worn-out scientist. What an expanse of workable ground your indefatigability opens to view! Long may you retain the powers exemplified in the manuscript I now return. With kindest regards and every good wish.

[p.86] In a letter of 14th March 1888, to the author’s wife, Owen wrote:—

Accept my grateful and respectful thanks for the copy of your interesting “Note on Degenerated Specimens of Tulipa sylvestris.” If ladies with similar gifts of observation, and equal power of clear exposition, would as kindly bestow them, science would benefit more largely and rapidly than at present. I avail myself of this opportunity of also thanking your gifted husband for the valuable paper “On the Problematical Organs of the Invertebrata,” which accompanied your gift.

In 1856 Owen was appointed Superintendent of the Department of Natural History in the British Museum, and his acceptance of this office necessitated the severance of his connection with the Royal College of Surgeons. The natural history collections at the British Museum were so extensive, and increasing so rapidly, that urgent demands for more space had frequently been made, and Owen took up the question with his usual enthusiasm. Ultimately the handsome building at South Kensington was erected, and from 1880 to 1884 Owen was engaged in superintending the removal of the collection. Owen could not but look with pride on the splendid result of his labours. It was the embodiment of what may be called one of the dreams of his life. Absorbing as his official duties often were, he did not permit them to stand in the way of his researches; and during the twenty-seven years of his connection with the British Museum he made numerous and valuable contributions to science.

Altogether he published nearly seven hundred memoirs, [p.87] books, etc. He served on several public commissions, received a civil list pension, and all the honours and distinctions usually awarded to men of science. Among these may be mentioned that he was elected, on 25th April 1859, one of the eight foreign associates of the Académie des Sciences; and in 1884 Queen Victoria conferred a K.C.B. He was also a chevalier of the orders: Pour le Mérite, Légion d’Honneur, Sts Maurice and Lazarus of Italy, the Rose of Brazil and Leopold of Belgium. Owen was also LL.D. of Edinburgh and Cambridge, and D.C.L. of Oxford Universities; and he received medals from the Royal, Linnean, and Geological Societies, and the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons. He was an honorary member of most of the learned academies and societies of the world. In fact, few men of science have ever received more numerous marks of distinction than Owen.

In 1852 Queen Victoria had shown her respect by granting him Sheen Lodge, Richmond Park; and there he lived for the remainder of his long life. Owen resigned his official post at the Natural History Museum in 1883, at the age of seventy-nine. Although full of years, he had lost little of his mental vigour, and he continued to work in his retirement.

To talk to Sir Richard Owen was to be struck by the vastness of his knowledge, and “the noble dignity of his personal character was in every way worthy of his fame.” To be in his company was to feel that one was in the [p.88] presence of a genius. Nearly every one of his memoirs represents a large amount of laborious research, and in the aggregate they bear ample testimony to the soundness of that consensus of opinion which stamps Sir Richard Owen as the greatest palæontologist since Cuvier, and a comparative anatomist only second in the immensity and importance of his labours to Hunter himself.

Owen was a most interesting and charming character; was a prodigious and untiring worker; lived a long, active, public life; knew nearly everybody who was worth knowing; a friend of royalty, and to the earnest worker “a guide, philosopher, and friend.”

Devoid of the least superstition, Owen told excellent ghost stories. These were famous and blood-curdling, and on many occasions he was particularly requested to narrate one or more of them. The stories were based on facts, which made them all the more interesting.

No man, not even Cuvier, has done so much as Owen to recreate the past, in visiting the “valley of dry bones” and informing these remains with the strange and weird life that endowed them; and in restoring in vivid outline that ancient world when huge “dragons of the prime” wallowed in the basins of the Thames and Seine, and when in a later age tigers, lions, hyænas and their kin contested with primitive man the supremacy of the sites where now London and Paris stand. It is pleasing to contemplate such pictures of the world’s past. Who, outside scientific [p.88] circles, would imagine that the elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, bear, and other animals lived in England, France, Germany, and other parts of Europe?

Owen in his Palæontology states that “more true turtles have left their remains in the London clay at the mouth of the Thames than are known to exist in the world.” What a difference from to-day!

Concerning Owen’s attitude towards Darwinism, it may be stated that Herbert Spencer was no strict Darwinian, for he remained, like Haeckel and others, a firm believer in Lamarckism.

Early in 1890 Sir Richard Owen was seized with a paralytic stroke, from which he never entirely recovered, but lingered on until 18th December 1892, when he passed peacefully away.

Speaking of his own work, he wrote to the author on 26th December 1887, as follows:—

Your kindly greetings are always welcome; they brighten declining years with failing strength. But bright gleams, as such are, enliven an old worker who can look back with some satisfaction. The sun is now shining in upon my writing-table on a pile of friendly letters that must be acknowledged by yours very truly, Richard Owen.

Owen would have been buried in Westminster Abbey if it had not been his wish to be laid in the same grave as his wife (who died on 7th May 1872). Both lie buried in Ham churchyard.

[p.90] At a public meeting on 21st January 1893, King Edward (then Prince of Wales) spoke of Owen as follows:—

The name of Sir Richard Owen must always go down to posterity as that of a great man—one who was eminent in the sciences of anatomy, zoology, and palæontology. … His geniality, his charm of manner to all those who knew him, will, I am sure, have left a deep and lasting impression. … His method of teaching was earnest and clear in every respect, and it even gained a certain force from the hesitation in his manner. A marble statue has been erected to the memory of Owen, and it adorns the hall of the Natural History Museum.

Sir Richard Owen rests from his labours, “and with his own right hand he carved his path from obscurity to a scientific throne. He stands among the sceptred immortals.”

1 An interesting aside about the author: While finding that books by A.B. Griffiths typically received good reviews, Webmaster found elsewhere several critical comments that Griffiths accepted payment for providing testimonial certificates that were included in advertisements by purveyors of quack or suspect products.

2 The English translation of Cicero’s De Officiis by Walter Miller, gives the quotation spelled as: Neque solum vivi atque præsentes studiosos discendi erudiunt, atque docent; sed hoc etiam post mortem monumentis litterarum assequuntur, (“And not only while present in the flesh do they teach and train those who are desirous of learning, but by the written memorials of their learning they continue the same service after they are dead”). From T.E. Page and W.H.D. Rouse (eds.), The Loeb Classical Library, Cicero: De Officiis (1913), Book I, xliv, 158-159. (source)

3 The quote by the author, A.B. Griffiths is from his Respiratory Proteids: Researches in Biological Chemistry (1897), Preface, iv.

4 From a longer quote in article, 'Chemistry', written by Henry E. Armstrong, for Encyclopedia Britannica (10th ed., 1902), 714.]

- Science Quotes by Sir Richard Owen.

- 20 Jul - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Owen's birth.

- Biography of Richard Owen - from The Speaker (1892).

- Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin, by Nicolaas A. Rupke. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Richard Owen.