(source)

(source)

|

Srinivasa Ramanujan

(22 Dec 1887 - 26 Apr 1920)

Indian mathematician who displayed a natural ability in mathematics at an early age. His talent was recognized by G. H. Hardy, who arranged for him to be a student at Cambridge University. In the following few years, before an early death at age 32, Ramanujan produced an exceptional output in mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series and continued fractions.

|

THE LATE MR. S. RAMANUJAN, B.A., F.R.S.

By P. V. Seschu Aiyar.

From The Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society (Jun 1920)

[p.81] As very little is known to the public of the private life of the late Mr. Ramanujan, a few personal details, such as the present writer was privileged to know and learn, may not be out of place in this memorial number of the Journal.

Srinivasa Iyengar Ramanuja Iyengar was born on the 9th day of Margasirsha in the Samvat Sarwajit answering to the English date of 22nd of December 1887, in the house of his maternal grandfather at Erode, that picturesque spot in South India in whose neighbourhood the Bhavani with overflowing waters meets and combines with the Cauvery. His parentage was humble; his father and his paternal grand-father were both accountants (literally gumastas) to cloth merchants at Kumbakonam, while his mother’s father had entered Government service as amin in the Munsiff’s Court at Erode. His mother, who survives him in great sorrow, is a shrewd and cultured lady, and Ramanujan took his features after her. As is usual with Brahmin boys, he was put to school at the age of five, and before seven he was transferred to the Town High School, Kumbakonam. Even at that early age, he used to puzzle his parents and teachers with questions about zero and imaginary quantities, the distances between the stars and the earth, and the like.

From boyhood, Ramanujan was found to be of a contemplative mood and sedentary in habits; he seldom associated with his school-mates at play. A correspondent, who was Ramanujan’s class-mate at Kumbakonam, [p.82] kindly sends me a description of his early life at school as follows: “Throughout his school course be held a freescholarship, and his teachers had already noticed his extraordinary and precocious intellect. He used to borrow Carr’s Synopsis of Pure Mathematics from the College Library, and took delight in verifying some of the formulæ given there. He would clear in half the time examination papers in Algebra and Geometry and a few seconds’ thought always used to suggest to him, the solution to any question however difficult. He used often to entertain his friends with his “theorems and formulæ” even in those early days, which doubtless appeared to his hearers as mathematical tricks. He had a distinctly religious turn of mind, and was a staunch believer in Hinduism. He never missed, if he could help it, a single sravanam ceremony at the Uppiliappan Koil near Kumbakonam. No wonder then that while at Cambridge he could not be persuaded to take the food cooked by others, and always cooked his own food. He had an extraordinary memory and could easily repeat the complete lists of Sanskrit roots (atmanepada and parasmepada); he could give the values of √2, π, e, etc., to any number of decimal places. In manners, he was simplicity itself. On one occasion when I was seriously laid up with fever just before the Matriculation Examination, he used to read for me every night. After his return from England and during his brief stay at Kumbakonam, he insisted on seeing my aunt, who is an old widow on the wrong side of 70, whom he knew while at school some 20 years ago, Perhaps, Ramanujan’s peculiar frame of mind and philosophic temperament is forcibly illustrated by the following incident: when about to undergo a serious operation under chloroform at Kumbakonam, he was trying to discover within himself as to which of the five senses lost its power first and which afterwards. * * *”

One of his old school teachers also contributes a similar account, adding that, while yet in the Sixth Form, Ramanujan used to interest himself with problems of plane and spherical trigonometry.

From the Town High School, he passed his Matriculation Examination in 1903, and entered the Government College, Kumbakonam, in 1904 for the F. A. course. As a result of a competitive examination in Mathematics and English Composition, Ramanujan secured the Junior Subramaniam Scholarship. It was there that I, the present writer, came in contact with Mr. Ramanujan for the first time, when I was Lecturer in Mathematics at the Government College. He went to me with a number of results in Finite and Infinite series, which at once struck me as something very ingenious and original. I exhorted him to go on with his results without at the same time neglecting his other studies. Unfortunately [p.83] however, he was found too weak in English to deserve promotion to the Senior F. A. class in January 1905. He had therefore to forgo also his scholarship at the college, and being too sensitive to ask his parents for help, he next moved to Vizagapatam to see if he could shift for himself to go on with his studies. Not receiving much encouragement there, he came to Madras, joined the Pachaiyappa’s College and presented himself for the First Examination in Arts in December 1906 without, as is well-known now, any success. He never repeated his attempt. Till 1909 he was doing nothing very particular, but continued working at Mathematics in his own way and jotting down his results in two good-sized note-books. In the summer of 1909 he married, and his University career abruptly ending, he was in search of a suitable employment to settle down in life.

To this end, he went to Tirukoilur, a small sub-division town in South Arcot District, to see Mr. V. Ramaswami Aiyar, the Founder of the Indian Mathematical Society, but Mr. Aiyar, seeing his wonderful gifts, persuaded him to go to Madras. It was then after some 4 years interval, that Mr. Ramanujan met at Madras, with his two well-sized note-books referred to above. I sent Ramanujan with a note of recommendation to that true lover of Mathematics, Dewan Bahadur R. Ramachandra Rao, who was then District Collector at Nellore, a small town some 80 miles north of Madras. Mr. Rao sent him back to me saying that it was cruel to make an intellectual giant like Ramanujan rot at a mofussil1 station like Nellore, and recommended his stay at Madras, generously undertaking to pay Mr. Ramanujan’s expenses for a time, This was in December 1910. After a while, other attempts to obtain for him a scholarship having failed, and Ramanujan himself being unwilling to be a burden on anybody for any length of time, he decided to take up a small appointment under the Madras Port Trust in 1911,

But he never slackened his work at Mathematics. His earliest contribution to the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society was in the form of questions communicated by me in Vol. III (1911). His first long article on “Some Properties of Bernoulli’s Numbers” was published in the December number of the same volume. Mr. Ramanujan’s methods were so terse and novel and his presentation was so lacking in clearness and precision, that the ordinary reader, unaccustomed to such intellectual gymnastics, could hardly follow him. This particular article was returned more than once by the Editor before it took a form suitable for publication. It was during this period that he came to me one day with some theorems on Prime Numbers, and when I referred him to Hardy’s Tract on “Orders of Infinity,” he observed that Hardy had said on p. 36 of his Tract “the exact order of ρ(x), [p.84] [defined by the equation ρ(x) = φ(x) − ![]() dt/log t, where φ(x) denotes the number of primes less than x], has not yet been determined” and that he himself had discovered a result which gave the order of ρ(x). On this I suggested that he might communicate his result to Mr. G. H. Hardy together with some more of his results. That communication excited Mr. Hardy’s interest in Ramanujan which never abated, and Mr. Hardy promptly replied in a very kind and appreciative letter, expressing admiration at some of the results and desiring to see more of Ramanujan’s work with proofs. This was answered by Ramanujan at some length, and these two letters were enough to rouse interest in Mr. Hardy; he proposed that Mr. Ramanujan should go to Cambridge and wrote to a friend at Madras to induce him to accept the proposal, Mr. Ramanujan however declined, on religious grounds, to go then but set to work more vigorously than ever.

dt/log t, where φ(x) denotes the number of primes less than x], has not yet been determined” and that he himself had discovered a result which gave the order of ρ(x). On this I suggested that he might communicate his result to Mr. G. H. Hardy together with some more of his results. That communication excited Mr. Hardy’s interest in Ramanujan which never abated, and Mr. Hardy promptly replied in a very kind and appreciative letter, expressing admiration at some of the results and desiring to see more of Ramanujan’s work with proofs. This was answered by Ramanujan at some length, and these two letters were enough to rouse interest in Mr. Hardy; he proposed that Mr. Ramanujan should go to Cambridge and wrote to a friend at Madras to induce him to accept the proposal, Mr. Ramanujan however declined, on religious grounds, to go then but set to work more vigorously than ever.

Meanwhile an event occurred which served to push Mr. Ramanujan into public notice and in fact accelerated his voyage to England. Dr. Gilbert T. Walker of the Meteorological Department, when on an official visit to Madras, noticed Mr. Ramanujan’s work through the kind offices of Sir Francis Spring, the President of the Port Trust. Dr. Walker immediately realised that a great mathematician was being made to rot in the Port Trust Office. He and Sir F. Spring forthwith induced both the Government and the University of Madras to award Mr. Ramanujan a University Research Scholarship, accordingly a studentship of Rs. 75 per mensem2; for a period of two years was awarded to him, thus setting him free for mathematical work entirely.

While he was thus engaged as a Research student, Mr. E. H. Neville, then of Trinity College, Cambridge, came to Madras (in January 1914) to deliver a course of University Lectures on Differential Geometry; and Mr. Hardy had requested Mr. Neville to bring Mr. Ramanujan with him to Cambridge. Accordingly, Mr. Neville, assisted by Sir Francis Spring and the Hon’ble Mr. R. Littlehailes3, succeeded in influencing the Government of Madras to grant Mr. Ramanujan a liberal scholarship and passage money to enable him to go to Cambridge. Mr. Ramanujan himself was quite willing now to proceed to England and, fortunately or otherwise, Ramanujan sailed for England about the end of March 1914. And just prior to that, the event was marked by a public demonstration held in [p.85] honour of him by his admirer and well-wisher Mr. S. Sreenivasa Iyengar, Ex-Advocate-General.

His work in England is narrated in appropriate and enthusiastic terms by Mr. Hardy in his official report printed in the issue of this Journal for February 1917. And as one reads again the obituary notice of Ramanujan [p.85] published by the same genial friend in “Nature” of June 1920,4 the heart heaves up with melancholy pride.

Reflecting upon this obituary notice and as well as generally upon Mr. Ramanujan’s University career, one is forced to admit that Mr. Ramanujan’s achievement was a glaring condemnation of the wooden system of our present University education which caters only for the average student and which tries, if possible, to stifle originality and reduce all to a dead level.

It is evident, however, that cruel fate was busy all through his stay at Cambridge, stealthily weakening his health and diminishing his strength, An insidious disease hard to diagnose, and difficult to cure was slowly undermining poor Ramanujan, who however fought against it nobly and courageously. Amidst foreign environments his food was by no means native, and the ailment which caused him pain was strange; and adding to this his peculiar temperament, incessant sedentariness and intense study, one can easily imagine his frail body weakening under the tightening grip of the tuber bacilli. Thanks mainly to the almost parental solicitude of that genial professor, Mr. G. H. Hardy, the best medical aid and nursing attendance was procured for him. And he struggled on with admirable fortitude. There are no papers and researches of his more valued nor more intuitive than those which he thought out during these fateful days. His physical body was failing no doubt, but his intellectual vision grew proportionately keener and brighter—illustrating here again his truly Indian philosophic spirit of self-sacrifice amidst worldliness and materialism. He fully vindicated in the very temple of European learning, where England’s sons themselves invoke the muse of number-mystery, the Indian’s grit for originality, and for startling discovery. Mr. Ramanujan’s disease had assumed serious proportions by the Christmas of 1918 and caused such grave anxiety to his doctors in England, that, hoping to do him good, they advised him to return to his native home in India,

When he arrived in Madras in April 1919, he was very weak and had been reduced to a skeleton. He was lodged in a bungalow in Mylapore and was treated for tuberculosis. At first he seemed to improve slowly and in June 1919 he went for a change to Kodumudi, a cool and bracing place on the banks of the Cauvery. While there, he got slightly better and it was thought he had no specific complaint except weakness, and that with his accustomed food and usual company at Kumbakonam, he would rally, He actually went to Kumbakonam in September and lived peacefully until January 1920, when there was the final and fatal relapse. He was immediately removed to Madras and placed under the treatment of expert doctors. His philanthropic well-wisher, Mr. S. Sreenivasa Iyengar, C. I. E., [p.86] came generously forward to defray all the expenses for his nursing and medical treatment; and accordingly he was housed in a neat cottage at Chetput, and was placed under the observation of Dr. P. S. Chandrasekharan, who did his best for him in consultation with Surgeon-General Giffard and other able doctors. But all was in vain. Ramanujan himself knew that his end was nearing. He answered the voices and visions which the living do not hear or see. and with courage, peace and good cheer, he passed away at sunrise on the 26th of April 1920, surrounded by a small circle of his friends and relatives, but mourned by an infinite circle of ever-increasing admirers.

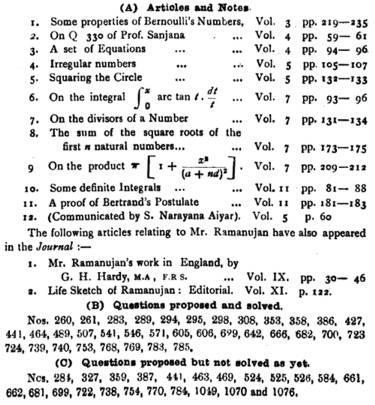

Mr. S. Ramanujan’s contributions to the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society were the following :—

2 per mensem — (L.) per month.

3 Richard Littlehailes C.I.E. (1878–1950) was a British educationist and administrator who spent most of his career in India, including as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Madras (1934-37). C.I.E. is an order of chivalry, Companion of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire.

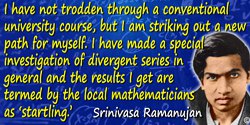

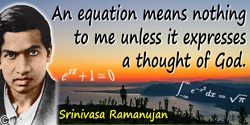

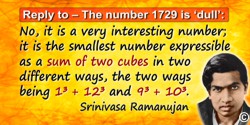

- Science Quotes by Srinivasa Ramanujan.

- 22 Dec - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Ramanujan's birth.

- Large color picture of Srinivasa Ramanujan (800 x 850 px)

- The Mystery of Srinivasa Ramanujan's Illness - was it tuberculosis or something else?

- The Man Who Knew Infinity, by Robert Kanigel. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Srinivasa Ramanujan.