(source)

(source)

|

Rudolf Virchow

(13 Oct 1821 - 5 Sep 1902)

German pathologist and statesman who originated the concept that disease arises in the individual cells of a tissue and, with publication of his Cellular Pathology (1858), founded the science of cellular pathology.

|

Rudolf Virchow

Obituary, in Harper’s Weekly (1902)

In the death of Professor Rudolf Virchow, which took place in Berlin on September 5, Germany loses one of her most picturesque figures, and the world one of its greatest scientists.

Professor Virchow had been famous for more than forty years as the founder of the theory of cellular pathology. He applied the theory of the cell as the basis of organic life to diseased tissues in the human body, proving that what we term disease is the expression of the abnormal action or development of those cells of which the tissues are ultimately composed. This theory gave the first rational basis to modern pathology, and forms the ground-work upon which all later developments of the subject are based.

This was Virchow’s greatest contribution to human knowledge; it is the secure basis of his lasting fame. But this is by no means the only field he entered as an originator. For example, he was one of the first to make a scientific study of the races of mankind, and he became one of the founders, as he remained a chief exponent, of the modern science of anthropology. The great pathologist and technologist was also a practical politician. Just forty years ago he entered the Lower House of the Prussian Legislature, and from 1880 till 1893 he was a member of the Reichstag. Here he showed the same originality that made him a discoverer in science. He was one of the founders of the famous Fortschrittspartie, and was the author of the word “Kulturkampf,” which came to be so prominent a political war-cry. In earlier life his radicalism sometimes got him into difficulties, as in 1849, when for political reasons he lost his position in the Charité hospital.

In later years his progressive ideas brought him repeatedly into conflict with Bismarck, but now his fame as a scientist stood him in good stead, even against the assaults of the Iron Chancellor. Nowhere else is versatility so frowned upon as in Germany. In general, it is counted almost a crime against scholarship there for one man to pretend to know more than one subject. But Virchow was excepted from this criticism, and listened to with respect on any topic. “Ah, Virchow knows everything,” said a Berlinite to whom I mentioned his name; and this seemed to voice the general sentiment. The physician, pathologist, anthropologist, and parliamentarian had proved his capacity in too many fields to have it questioned in any. It seemed as fitting that he should assist Schliemann in his excavations at Hissarlik, and write a scholarly essay about Troy, as that he should lead a debate in the Legislature, conduct a reform in the sewage system of Berlin, organize an anthropological society, preside at a meeting of the Academy of Medicine, discuss Roman archæology with Mommsen at the Academy of Science, or deliver a lecture on the blood at the Pathological Institute: everywhere he seemed equally at home.

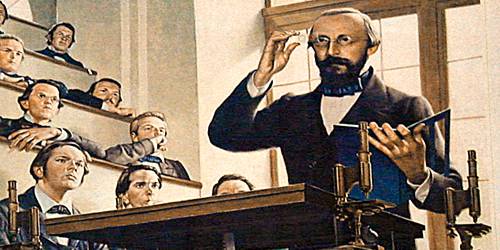

If one were to choose, perhaps he might say that no rôle suited the versatile scholar better than that of lecturer. He was preeminently a teacher, and while not at all oratorical, his impromptu discussions before his medical class, aided by offhand chalk pictures, had a fervor that held the attention of his audience and carried conviction.

The home life of Professor Virchow was refreshingly simple by contrast. One found the famous scientist living in a small apartment, up several rather forbidding flights of stairs; comfortably housed, to be sure, but on a scale which any but a mere beginner in the medical profession in an American city would consider rather beneath his dignity. Professor Virchow was most hospitable to strangers, in spite of the demands upon his time.

He was particularly cordial to Americans, and he conversed fluently in English. In talking with the present writer recently he expressed the keenest interest in American affairs. Commenting on the dilapidated condition of his own Charité hospital, he remarked, with a tone of regret, “You see, we have no millionaires here to give us such beautiful hospitals as you have in America.” He added: “Some day I mean to come over there to see all the wonderful things we read about. Hitherto the difficulties of ocean travel have kept me from coming; but one of these days, when steamboats are swifter, I shall certainly come.” That was a cheery view for an octogenarian. But the expectation was not to be realized; the great pathologist died just before completing his eighty-first year.

- Science Quotes by Rudolf Virchow.

- 13 Oct - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Virchow's birth.

- Professor Rudolf Virchow Biography - Popular Science Monthly (Oct 1882)

- Collected Essays on Public Health & Epidemiology, by Rudolf Virchow. - book suggestion.