(source)

(source)

|

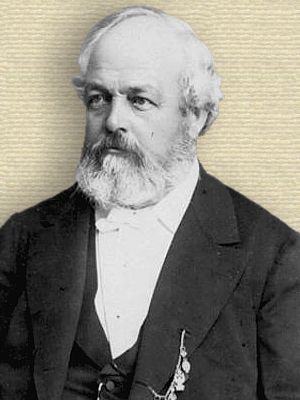

Robert Whitehead

(3 Jan 1823 - 14 Nov 1905)

English engineer who invented the modern sub-surface, self-propelled torpedo, which he sold to a number of countries.

|

Robert Whitehead

by S. E. Fryer

from Dictionary of National Biography (1912)

[p.650] WHITEHEAD, ROBERT (1823-1905), inventor, born at Mount Pleasant, Bolton-le-Moors, Lancashire, on 3 Jan. 1823, was one of a family of four sons and four daughters of James Whitehead (1788-1872), the owner of a cotton-bleaching business at Bolton-le-Moors, by his wife Ellen, daughter of William Swift of Bolton. Educated chiefly at the local grammar school, he was apprenticed, when fourteen, to Richard Ormond & Son, engineers, Aytoun Street, Manchester. His uncle, William Smith, was manager of the works, where Whitehead was thoroughly grounded in practical engineering. He also acquired unusual skill as a draughtsman by attendance at the evening classes of the Mechanics’ Institute, Cooper Street, Manchester. Meanwhile his uncle became manager of the works of Philip Taylor & Sons, Marseilles, and in 1844 Whitehead, on the conclusion of his apprenticeship, joined him in that employ. Three years later he commenced business on his own account at Milan, where he effected improvements in silk-weaving machinery, and also designed machinery for the drainage of some of the Lombardy marshes. His patents, however, as granted by the Austrian government, were annulled by the Italian revolutionary government of 1848. Whitehead then went to Trieste, where he served the Austrian Lloyd Company for two years; from 1850 to 1856 he was manager there of the works of Messrs. Strudhoff. In 1856 he started for local capitalists, at the neighbouring naval [p.651] port of Fiume, the Stabilimento Tecnico Fiumano.

At Fiume, Whitehead designed and built engines for several Austrian warships, and the high quality of his work led to an invitation in 1864 to co-operate in perfecting a ‘fireship’ or floating torpedo designed by Captain Lupuis of the Austrian navy. The officer’s proposals were dismissed by Whitehead as too crude for further development. At the same time he carried out with the utmost secrecy, in conjunction with his son John and one mechanic, a series of original experiments which culminated in 1866 in the invention of the Whitehead torpedo.

The superiority of the new torpedo over all predecessors was quickly established. But it lacked precision, its utmost speed and range were seven knots for seven hundred yards, and there was difficulty in maintaining it at a uniform depth when once in motion. The last defect Whitehead remedied in 1868 by an ingenious yet simple contrivance called the ‘balance chamber,’ the mechanism of which was long guarded as the ‘torpedo’s secret.’ In the same year, after trials from the gunboat Gemse, the right, though not exclusive right, of construction was bought by the Austrian government, and a similar right, as the result of trials off Sheerness in 1870, was bought by the British government in 1871. France followed suit in 1872, Germany and Italy in 1873, and by 1900 the right of construction had been acquired by almost every country in Europe, the United States, China, Japan, and some South American republics. Meanwhile Whitehead in 1872 had in conjunction with his son-in-law, Count Georg Hoyos, bought the Stabilimento Tecnico Fiumano, devoting the works solely to the construction of torpedoes and accessory appliances. His son John subsequently became a third partner. In 1890 a branch was established at Portland Harbour, under Captain Galway, an ex-naval officer, and in 1898 the original works at Fiume were rebuilt on a larger scale.

Repeated improvements were made upon the original invention, many of them being by Whitehead and his son John. In 1876 by his invention of the ‘servo-motor,’ which was attached to the steering gear, a truer path through the water was obtained. In the same year he designed torpedoes with a speed of eighteen knots for six hundred yards, while further changes gave a speed in 1884 of twenty-four knots, and in 1889 of twenty-nine knots for one thousand yards. Means were also devised by which the torpedo could be fired from either above or below the surface of the water and with accuracy from the fastest ships, no matter what the speed or bearing of the enemy. Each individual torpedo, however, continued to show idiosyncrasies which required constant watching and correction, and absolute confidence in the weapon was not established till the invention in 1896, by Mr. Obry, at one time of the Austrian navy, of a small weighted wheel, or gyroscope, which acted on the ‘servomotor’ by means of a pair of vertical rudders and steered a deflected torpedo back to its original course. The invention, which disarmed the torpedo’s severest critics, was acquired and considerably improved by Whitehead. In its present form the Whitehead torpedo is a weapon of precision, its capabilities entirely eclipsing those of the gun and ram. Any doubts as to its usefulness in war were definitely dispelled by the ease with which on 9 Feb. 1904 a few Japanese destroyers reduced the Russian fleet outside Port Arthur to impotence.

Whitehead received many marks of favour and decorations from various courts. He was presented by the Austrian Emperor with a diamond and enamel ring for having designed and built the engines of the ironclad Ferdinand Max, which rammed the Re d’Italia at the battle of Lissa. On 4 May 1868 he was decorated with the Austrian Order of Francis Joseph in recognition of the excellence of his engineering exhibits at the Paris Exhibition in 1867. He also received Orders from Prussia, Denmark, Portugal, Italy, Greece, France (Legion of Honour, 30 July 1884), and Turkey. Whitehead did not apply for Queen Victoria’s permission to wear his foreign decorations.

Whitehead for some years owned a large estate at Worth, Sussex, where he farmed on a large scale. He died at Beckett, Shrivenham, Berkshire, on 14 Nov. 1905, and was buried at Worth, Sussex.

Whitehead married in 1845 Frances Maria (d. 1883), daughter of James Johnson of Darlington, by whom he had three sons and two daughters. His eldest son, John (d. 1902), assisted him at Fiume and made valuable improvements in the torpedo. The second daughter, Alice (6. 1851), married in 1869 Count Georg Hoyos. A portrait of Robert Whitehead by the Venetian artist, Cherubino Kirchmayr, belongs to his grandson, John Whitehead (son of John Whitehead). The original sketch in oils of a second portrait by the same artist is owned by Sir James [p.652] Beethom Whitehead, K.C.M.G. (the second son), British minister at Belgrade since 1906; the finished portrait belongs to Robert Bovill Whitehead (the third son).

- 3 Jan - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Whitehead's birth.

- The Devil’s Device: The Story of Robert Whitehead, by Edwyn Gray. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Robert Whitehead.