(source)

(source)

|

John Wilson

(1696 - 15 Jul 1751)

English botanist who was the first to attempt a systematic arrangement of the indigenous plants of Great Britain in the English language

|

John Wilson

Biography from The Gentleman's Magazine (1791)

A SHORT life of the subject of the present essay may be found in Pulteney's History of Botany in England, vol II. p. 264; where we are informed, that the principal circumstances are borrowed from the British Topography. As this account is far from being correct, it is presumed that the following may be offered to the Gentleman's Magazine without farther apology.

Some Account of John Wilson, Author of the Synopsis of British Plants in Mr. Ray's Method.

JOHN WILSON, the first who attempted a systematic arrangement of the indigenous plants of Great Britain in the English language, was born in Longsleddal, near Kendal, in Westmoreland, some time in the year 1696. He was by trade a shoe-maker, and may be ranked amongst the few who, in every age, distinguish themselves from the mass of mankind by their scientific and literary accomplishments, without the advantages of a liberal education. The success of his first calling does not appear to have been great, as perhaps he never followed it in a higher capacity than that of a journeyman. However this may be, he exchanged it, for the more lucrative employment of a baker, soon enough to afford his family the common conveniences of life; the profits of his new business supporting him in circumstances which, though not affluent, were far superior to the abject poverty he is said to have experienced, by the author of the British Topography. This writer, amongst other mistakes undoubtedly occasioned by false information, has recorded an anecdote of him, which is the fabrication of one of those inventive geniuses who are more partial to a good tale than attentive to the truth. He acquaints us, that Wilson was so intent on the pursuit of his favourite study, as once to be tempted to sell a cow, the support of his house, in order to procure the means of purchasing Morrison's voluminous work; and that this absurd design would have certainly been put in execution, had not a neighbouring lady presented him with the book, and by her generosity rescued the infatuated botanist from voluntary ruin. The story is [p.233] striking, but wants authenticity; and is absolutely contradicted by authority that cannot be disputed. At the time when Wilson studied botany, the knowledge of system was not to be obtained from English books; and Ray's botanical writings, of whose method he was a perfect master, were all in Latin. This circumstance makes it evident, that he acquired an acquaintance with the language of his author, capable of giving him a complete idea of the subject. The means by which he arrived at this proficiency are not known at present; and though such an attempt, made by an illiterate man, may appear to be attended with insuperable difficulties to those who have enjoyed a regular education, yet the experiment has been frequently made, and has been almost as frequently successful. No one ought to be surprised with the apparent impossibilities that perseverance constantly vanquishes, when properly stimulated by the love of knowledge. The powers of industry are not to be determined by speculation; they are seen and understood by their effects: it is this talent alone that forms the basis of genius, and distinguishes a man of abilities from the rest of his kind.

It was no easy undertaking to acquire the reputation of an expert and accurate botanist before Linnaeus's admirable method of discriminating species gave the science so essential an improvement.

The subject of the present essay overcame the difficulties inseparable from the enterprize, and merited the character from his intimate acquaintance with the vegetable productions of the North of England. But there is good reason to believe that he was not entirely self-taught; for, under the article Gentiana, he accidentally mentions his intercourse on the subject with Mr. Fitz-Roberts, who formerly resided in the neighbourhood of Kendal, and was known to Pettiver and Ray: his name occurs in the Synopsis of the latter gentleman. The numerous places of growth of the rarer plants added by Wilson to those found in former catalogues, shew how diligently he cultivated the practical part of botany.

It will appear a matter of surprise, to such as are ignorant of his manner of life, how a mechanic could spare a very large portion of time from engagements which ought to engross the attention of men in low circumstances, for the sole purpose of devoting it to the curious but unproductive researches of a naturalist. On this account it is proper to remark, that the business of a baker was principally managed by his wife, and that a long indisposition rendered. [p.234] him unfit for a sedentary employment. He was afflicted with a severe asthma for many years, which, while it prevented him from pursuing his trade as a shoe-maker, encouraged the cultivation of his favourite science, and he attended to it with all the ardour a sick man can experience. Fresh air, and moderate exercise, were the best palliatives of his cruel disease: thus he was tempted to amuse the lingering hours of sickness with frequent excursions in the more favourable parts of the year, as often as his health would permit; and, under the pressure of an unpropitious disorder, explored the marshes, and even the hills, of his native county, being often accompanied by such of his intimates as were partial to botany, or desirous of beholding those uncommon scenes of nature that can only be enjoyed in mountainous countries.

The singularity of his conversation contributed not a little to the gratification of his curiosity; for he was a diligent observer of manners and opinions, and delivered his sentiments with unreserved freedom. His discourse abounded with remarks, which were generally pertinent, and frequently original: many of his sententious expressions are still remembered by his neighbours and contemporaries. One of these deserves recording, as it shews that his knowledge of botany was not confined to the native production of England. Being once in the county of Durham, he was introduced to a person who took much pleasure in the cultivation of rare plants. This man, judging of his abilities by his appearance, and perhaps expecting to increase his own reputation by an easy victory over one he had heard commended so much, challenged him to a trial of skill; and, in the course of it, treated his stranger with a degree of disrespect that provoked his resentment, and prompted him to give an instance of his superiority. Accordingly, after naming most of the rarities contained in the garden, and referring to authors where they are described, he in his turn plucked a wild herb, growing in a neglected spot, and presented it to his opponent, who endeavoured to get clear of the difficulty by pronouncing it a weed; but Wilson immediately replied, a weed is a term of art, not a production of nature: adding, that the explanation proved his antagonist to be a gardener, not a botanist Thus the contest ended. These qualities, so uncommon in an unlettered man, procured him the notice of several persons of taste and fortune, whose hospitality enabled him to prosecute his researches on an (economical plan that suited his humble condition.

[p.235] Mr. Isaac Thompson, an eminent land-surveyor, resident at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, may be reckoned his steadiest patron, and warmest encourager; for he frequently accompanied this gentleman, when travelling in the line of his profession, under the character of an assistant,—an employment that left him at full liberty to examine the vegetable productions of the different places visited by them. But it is difficult to determine, at present, what experience he gained from his connection with Mr. Thompson; and the author of the present essay has scarcely any other means of discovering what were his opportunities of attending to the places of growth of the rarer plants, besides his own work the Synopsis, where the observations are in a great measure confined to Westmoreland and Northumberland. Perhaps this was done to accommodate his friends, who were numerous in those counties, and for whose use the book was chiefly intended: however, it appears from the volume itself, that he was not entirely unacquainted with the South of England. This work was published in the year 1744; it comprehends that part of Ray's method that treats of the more perfect herbs, beginning at the fourth genus, or class, and ending with the twenty-sixth. He promises, in the preface, to complete the performance at a future period, provided his first attempt should meet with a favourable reception from the public ; but did not live to fulfil his promise, being prevented by indisposition from finishing a second volume, which was intended to contain the Fungi, Mosses, Grasses, and Trees.

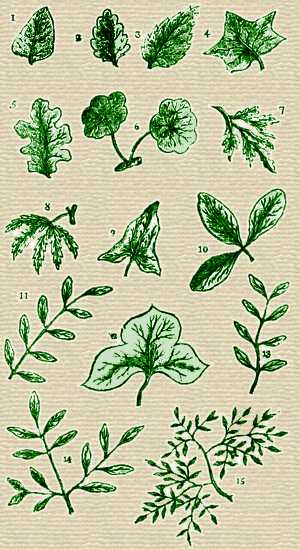

He died July 15, 1751, after lingering through the last three or four years of his life in a state of debility that rendered him unfit for any undertaking of the kind. Some papers left by him on the subject passed into the hands of Mr. Slack, printer, at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, but were never published. Among these were some drawings, but it is not certain whether they were representations of rare plants, or figures intended to illustrate the technical part of the science. The writings of Linnaeus became popular in England a short time after his death, and very soon supplanted all preceding systems; otherwise the character of Wilson had been better known to his countrymen at present. His Synopsis is certainly an improvement on that of Ray; for, besides some correction in the arrangement, many trivial observations are left out of it, to make room for generic and specific descriptions, the most essential parts of a botanical manual.

He did not increase the catalogue of British plants much, [p.236] only adding two to Ray's number, as distinct species, the AIlium schœnopprasum, and the Valeriana rubra; but he was the first who introduced the Circea alpina to the notice of the English botanist, as a variety of Chutitiana alpina growing near Sedberg, in Yorkshire.

- Science Quotes by John Wilson.

- 15 Jul - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Wilson's death.

- John Wilson - short biography from The Year Book of Daily Recreation and Information (1832).

- John Wilson - short biography from an article 'From A Country Parsonage', in The Gentleman's Magazine (1891).