Conservation Works and Pays

from The Rotarian (1938)

By William Vogt

Editor, Bird-Lore

[p.24] A GRAVE MARKER deep in the tangled jungles of Florida ... one boot on a lonely Virginia beach ... a bloody ax and a few human hairs. ... These are some of the dramatic chapter headings in one of the most remarkable stories of idealism in the history of the United States. Nothing but a love of birds inspired those who successfully fought powerful commercial forces and set up a system of protection that snatched winged America back from the brink of extermination.

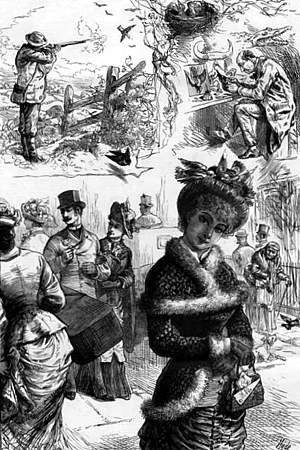

The story has its beginning in the days when women required feathers for their hats. In two afternoons, on 14th Street in New York City, one observer counted 40 kinds of feathered remains on women's hats!

The millinery industry claimed that it was founded on the feather trade, and nothing could exceed in acrimony what was said about Theodore Roosevelt when he made a few early efforts to reduce the kill of birds. Alfred E. Smith, later justly proud of his conservation record as Governor of New York State, fought bird-protection laws and contended that they would destroy a great industry! Thousands of men—it was said—depended on bird killing for their livelihood; to stop the killing would be to take food from their mouths.

We Americans are good natured and it takes a good while for us to get mad. But we have a way of being hardheaded about facts when we are finally aware of them. The facts about our birds were the sort that could not be ignored. The birds were being wiped out and, as a result, the country was losing irreplaceable assets.

First, the egrets had been almost entirely exterminated. These are immaculately white, long-legged, wading birds, with bright yellow bills and a grace no dancer has ever equalled. Their plumes, which were literally worth their weight in gold and twice that in London, were worn by the birds only at the nesting season. Few creations of Nature are more delicate than these feathers, and by the time the baby birds are able to shift for themselves the adult plumes are usually so worn and battered they would ornament neither bird nor woman. Plumes could be secured only by killing the birds. So killed they were.

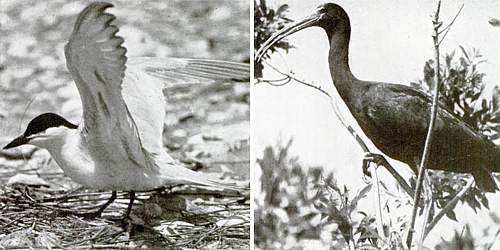

Twenty years ago the least tern, an exquisite cousin of the gulls, was a rarity in New York. Now it is commonplace and hundreds of thousands of people who have no idea of its name have taken pleasure in the swift delicacy of its glistening wings; its long, streaming, forked tail; its sharply cried kee-dick.

The terns, or sea swallows, nest in large colonies. Their eggs are deposited on the open beaches, often without any nest save a scraped-out hollow, and the human trespasser is likely to be assailed by a cascade of diving birds. With forked tail spread, they scream their protests and plunge at the interloper in breath-taking swoops. As they dive, they shriek, and many a time I [p.25] have seen a man or woman or dog frightened away by them.

But not a feather hunter! As the birds hang overhead, frantic for the safety of their eggs or young, it is an easy task to pick them off with a light shotgun. It is so easy that for hundreds of miles along the coasts of the United States the lovely sea swallows were virtually exterminated. A few years more and they might have been gone forever. But the people to whom America would not be America without its birds, said to the commercial exploiters, “You have no more right to these birds than we. We’re going to save the birds for our own enjoyment and our children’s.” And they did.

The sanctuary movement began in 1900. The first efforts were private. Government sanctuaries were established a bit later, but usually there was no money available for their operation. In 1902, the National Association of Aububon Societies,* primarily an educational institution, took up its sanctuary work. It realized that something more drastic than merely setting aside areas for the birds would be necessary. It began its work in earnest with a group of wardens who would enforce the law.

The first Audubon warden to be sent into Florida swamps, Guy Bradley, was murdered. With plumes sought in markets all over the world, with little chance of detection, arrest, and conviction, why stop at murder? A few years later Columbus McLeod, another Audubon warden, disappeared. His sunken boat was recovered—weighted down with sandbags to hide it permanently—and an ax, stained with blood and hair.

Dr. T. Gilbert Pearson, now president emeritus of the Audubon Association, was in Florida shortly after Bradley’s death, and hired a schooner to take him from Marco to Key West. The one-man crew of the little vessel, knowing nothing of the Northerner’s business, asked him, “Ever hear of this Audóobon Society?”

Dr. Pearson “allowed” as how he had, but, fortunately, was vague.

“Well,” opined the man, “they’re a bunch of damn’ Yankees, come down here tryin' to take the bread out of our mouths. They’re tryin’ to stop us from killin’ these birds. See this?”

This was a six-shooter—“with a barrel that looked as long as my arm,” Dr. Pearson says. “Well,” continued the boatman, “I’m goin’ to let daylight straight through the first Audóobon man I see. One of their men, Bradley, got killed last week, and he’s only the first of ’em.”

What manner of man is it who gives up his life for birds if necessary when hush money is an easy alternative? Florida’s Kissimmee prairie warden in many ways typifies the lot. Night and day, in all weathers, he goads his old car across savannas, through swales, constantly seeking the information on which an efficient protection program must be based. One of his many problems is the illegal egg collector, whose activities take the heaviest toll from birds that are nearest extermination. When he started work, every palmetto in which the rare Audubon’s caracara nested bore the marks of eggers’ climbing irons. Now they show where the warden has climbed—to stamp each egg with indelible ink: Protected by the National Association of Audubon Societies. These eggs are worthless to the collectors.

Many a so-called sanctuary is a sanctuary only by the grace of the warden. The birds—great ibises, relatives of the sacred bird of Egypt, rare cranes, brilliant pink spoonbills, egrets—may be nesting on private land or [p.26] State land. They may—and often do—shift about from place to place. It has not been feasible to attempt to buy all the land the birds need. While State and Federal laws give them current protection, in some parts of the United States, Government officers are rare, and the sole protection comes from Audubon wardens.

In other areas food, water, and cover conditions are exactly what the birds need, and the cheapest and most effective way of giving protection is to set aside tracts of land for them. The Paul J. Rainey Wild-Life Sanctuary in Louisiana, owned and maintained by the Audubon Association, is such an area. Twenty-six thousand acres in extent, it was made possible through the generosity of Mrs. Grace Rainey Rogers.

AT THE Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Sanctuary on Long Island, the concern has been to demonstrate ideal sanctuary conditions. By intensive propagation of food and cover plants, the bird population has been built up to one of the highest densities known—152 nests in 12 acres. This sanctuary is adjacent to Theodore Roosevelt's grave, and thousands of visitors to the area have here gained their first idea of what a bird sanctuary is.

Still a fourth type of sanctuary is one at Cape May Point, New Jersey. The long thrust of southern New Jersey acts as a funnel; migrating birds are concentrated here in such numbers in the Fall as, probably, can be seen no other place in North America. For many years the bird concentrations were followed by concentrations of gunners. An extensive and beautiful area at the point is now under lease to the Audubon Association, and a warden is stationed here from August to November every year.

Junior Audubon Clubs were first formed 28 years ago, through the generous donations of Mrs. Russell Sage and others, and more than 5,600,000 boys and girls have been enrolled. Two of the men on the present Audubon staff became interested in the work through Junior Clubs. Their single aim: conservation. Over 100 million pieces of educational material have been distributed.

The educational work has reached its highest development in the Audubon Nature Camp for adult leaders, on an island off Maine. Here, at less than cost, school superintendents, principals and teachers, Scoutmasters, camp counsellors, librarians, and other youth leaders come from all parts of the country—to learn of proved successful ways of stimulating lasting genuine interest of children in the outdoors.

What has been the net gain in the 38 years of conservation activity? A drive to the coast almost anywhere in the East will show the Summer visitors an abundance of birds that, three decades ago, were rarely to be seen except on a woman's hat.

Now in Florida the egret is abundant. The most spectacular and beautiful aspect of a drive across the Tamiami Trail is the birds. I have seen them there, literally by the thousand—egrets, ibises, snakebirds, wood ibises, and many others. Anyone who has watched a towering flock of white ibises, swinging in great circles with black-tipped white wings flashing in the sun, will remember this beauty of Florida.

In the late Summer thousands of egrets wander northward. One day last September I counted more than 100 of them feeding alongside the railroad track that skirts the Hudson. People crowded to the river windows to exclaim at the beauty of the “white cranes.”

BUT the increase in the number of birds is not the sole result. An almost universal charity for feathered wild life is another. Hundreds of thousands of people every Winter regularly feed birds. Killing is now almost entirely restricted to legitimate sport species. Even hawks and owls, once killed indiscriminately, are now protected in most States both by law and by sentiment.

This has resulted in a better America. Songbirds that were formerly killed now rear their families to help man control the insects. In the Theodore Roosevelt Sanctuary it has never been necessary to use an ounce of insecticide. On the farms the hawks and owls ceaselessly help man by keeping the rodents in check. On the Texas coast, where “crawfish” destroy levees about the rice fields, the herons and ibises, locally known as “levee-walkers,” are rightfully considered one of man’s [p.27] best friends. Anyone who shoots these birds ranks nearly as low as a horse thief. By restoring the birds we help to restore a natural balance favorable to man.

The struggle is not yet over. Until education has made the general public realize that a bird in the bush is worth two in the hand, it will be necessary to continue patrols. The destruction of forests, swamps, and prairies obliterates habitats without which wild life cannot survive. Many years more of work lie ahead of conservationists. State and Federal Governments are doing much for game birds, but actual protection of gulls, terns, cormorants, ibises, egrets, pelicans, snakebirds, and roseate spoonbills, to name but a few, still depends almost entirely on public-spirited citizens.

EVEN the hardest-headed and most skeptical businessmen are beginning to realize that bird protection pays—not only in terms of education and recreation, but also in the coin of the realm.

Evidence of this is to be found in many parts of the United States. The Canadians have wisely and widely publicized their sanctuary on Bonaventure Island, which attracts people every year from hundreds of miles away. A recent magazine article about birds of the Carolina coast brought so many visitors and cars that it was necessary to close off the road to a sanctuary near Charleston, South Carolina.

Thousands of visitors every Fall seek an isolated mountaintop in Pennsylvania where the majesty of the hawk migration sweeps by and where the field glass has replaced the repeating shotgun; farmers in the region have for the first time been able to put plumbing and electricity into their houses because of the profits from this new tourist trade. Cars from many States labor up the ancient rocky way from Drehersville, and this remote country has its first parking problem. On the mountaintop itself the problem is nearly as bad. The bare rocks are often so crowded that there is scarcely room for another bird student to stand and watch the procession of the hawks go by.

Every year Florida is a Mecca for thousands whose hobby is the enjoyment of birds. In my work I come in contact with these outdoor people in every State of the North and East; I have never talked Florida birds with any of them who did not plan to visit the State. The same is true of Louisiana and Texas.

Of course, one does not have to go to Florida or Texas or Louisiana to see birds. There are few counties in the United States that do not have, within their borders, more than 100 kinds every year. And anyone who will use a little ingenuity can create his own sanctuary in suburb, garden, or farm. The same formula may be used that has been so successful in Audubon sanctuaries: protection + cover + food + water = birds. Its success has been proved, time and again, for 38 years.

- 14 Mar - in 1903, Pelican Island was established as the first national bird sanctuary in the U.S.

- Pelican Island of Indian River - article from 1909 on the pelicans of Pelican Island, the first U.S. bird sanctuary.

- 9 Jan - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of birth of Paul Kroegel, first U.S. Game Warden at Pelican Island.

- America's National Wildlife Refuges: A Complete Guide, by Russell D. Butcher. - book suggestion.