Tunnels and Tunnelling.

A French engineer, M. Favre1, has recently proposed the construction of a tunnel under the waters of the Straits of Dover, to unite France and England, by a subterranean railway. Surveys of the route have been made; every foot of the English channel has been sounded, and recent English papers assert the practicability of the project. Its length, under water will be nineteen miles; and the entrances on land, to obtain the proper grade, will be about two miles long, making a total length of about twenty-one miles. Its walls are intended to be very thick, composed of huge granite blocks cemented together, and lined with a circular shield of perforated iron plates.

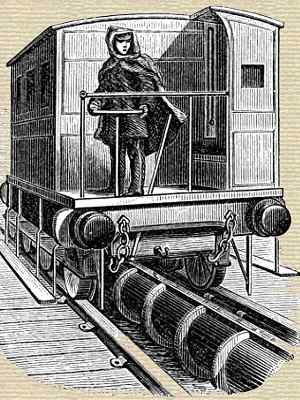

The railroad through it is intended to be operated by stationary engines, which are to drive the trains by compressed air, and thus avoid the heat and smoke, which would be entailed by the use of locomotives. In excavating this tunnel, M. Favre proposes to get rid of the excavations in a most ingenious and economical manner. The plan consists in building strong tall air shafts or chimneys for ventilation along its course, through which the excavated materials shall be lifted and thrown into the sea, forming little islands around the shafts, thus protecting them from the action of the waves. The whole cost of this great work, it is stated, will amount to but $10,000,000. In an article on this subject, in the New York Times of the 13th inst., we find the following remarks :—

“When Mr. Isambert Brunel2 projected the Thames Tunnel, people first scoffed at the feasibility of the undertaking, and then, when the great engineer demonstrated its practicability, by achieving his plan, they took to wondering of what earthly use this great expensive underground gallery could possibly be.

For a long time, we confess, we were rather skeptical of the practical benefit to he derived from Mr. Brunel’s splendid whim. We knew that certain people sold cakes and candy by gas-light in the Thames Tunnel to wondering country people, who paid their sixpences to walk through that great damp, moldy gallery; but there it seemed as if the commercial uses of the Tunnel ended. Now we know better. The successful accomplishment of the Thames Tunnel has directed the scientific mind in that line, and the result has been that we are, in five years from this time, to have a tunnel beneath the English Channel, running from Boulogne to Dover.”

The idea of tunnelling the river Thames is probably due to Ralph Dodd, a painter by trade, but an able amateur engineer, who proposed to construct a tunnel under the Thames at Gravesend, in 1798; and in 1807 Trevithick, the engineer, was employed to sink a shaft and commence a tunnel at Rotherhithe, in London, but the water and quicksand broke in upon his excavation and defeated his operations. The project was then abandoned until 1823, when a company was formed to carry out Brunel’s plan, which, after some reverses, was accomplished, and the Tunnel opened in 1843—twenty years after the company was formed. This tunnel is but 400 yards in length, yet it cost, from first to last, $2,273,000, while its annual receipts only amount to about $25,000.

Another engineer, Henry Mulliner, also proposes to construct a tunnel of huge iron tubes, made in sections, bolted and cemented together, and laid down in the Channel between France and England. He asserts that the bottom of the Dover Straits is suitable (it must be level for this purpose,) and that such a tunnel will be much cheaper than one which has to be excavated under the bed of the sea.

This plan looks far more feasible than the one suggested by Favre; but we have no idea that the Tunnel between France and England (eighty-three times the length of the Thames Tunnel) can be constructed for ten or twice ten million of dollars, taking the expense of the Thames Tunnel as a basis. Tunnels are the most expensive works of railroad engineering; and, like bridges, their expense increases in a quadruple ratio, according as their length is increased. This fact should not escape the attention of engineers when they enter into calculations upon enterprises of such magnitude.

2 a typo in the original newspaper, which should read “Isambard.”]

- Channel Tunnel Proposed in 1855 - New York Daily Times article.