(source)

(source)

|

Charles Martin Hall

(6 Dec 1863 - 27 Dec 1914)

American chemist who invented (1886) an inexpensive electro-chemical method to extract aluminium from its ore. The process quickly enabled commercial production of this metal, at prices competitive with steel and copper. Aluminium, once a precious metal used for fine jewelry, by 1914 was down to 18 cents a pound.

|

Invention of the Aluminum Process

by Charles Hall

Acceptance Speech for the Perkin Medal Award

from The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry (Mar 1911)

It has been suggested to me to give an account of some of the more personal and unpublished facts in connection with my invention of the aluminum process, and of the work of putting it on a commercial basis.

My first knowledge of chemistry was gained as a schoolboy at Oberlin, Ohio, from reading a book on chemistry which my father studied in college in the forties. I still have the book, published in 1841. It is minus the cover and the title-page, so I do not know the author. It may be interesting now to see what this book, published seventy years ago, says about aluminum: “The metal may be obtained by heating chloride of aluminum with potassium in a covered, platinum or porcelain crucible and dissolving out the salt with water. As thus prepared it is a gray powder similar to platinum, but when rubbed in a mortar exhibits distinctly metallic lustre. It fuses at a higher temperature than cast-iron and in this state is a conductor of electricity but a non-conductor when cold.”

Later I read about Deville’s work in France, and found the statement that every clay bank was a mine of aluminum, and that the metal was as costly as silver. I soon after began to think of processes for making aluminum cheaply. I remember my first experiment was to try to reduce aluminum from clay by means of carbon at a high temperature. I made a mixture of clay with carbon and ignited it in a mixture of charcoal with chlorate of potassium. It. is needless to say that no aluminum was produced. I thought of cheapening the chloride of aluminum, [p.147] then used as the basis for aluminum manufacture, and tried to make it by heating chloride of calcium and chloride of magnesium with clay, following the analogy by which iron chloride is produced when common salt is thrown into a porcelain kiln. A little later I worked with pure alumina and tried to find some catalytic agent which would make it possible to reduce alumina with carbon at a high temperature. I tried mixtures of alumina and carbon with barium salts, with cryolite, and with carbonate of soda, hoping to get a double reaction by which the final result would be aluminum. I remember buying some metallic sodium and trying to reduce cryolite but obtained very poor results. I made some aluminum sulphide but found it very unpromising as a source of aluminum then, as it has been ever since.

On a later occasion I tried to electrolyze a solution of aluminum salt in water, but found nothing but a deposit of hydroxide on the negative electrode. I did not give a great deal of time to these experiments, as I was then a student in college and was working on three or four other attempted inventions.

I had studied something of thermochemistry, and gradually the idea formed itself in my mind that if I could get a solution of alumina in something which contained no water, and in a solvent which was chemically more stable than the alumina, this would probably give a bath from which aluminum could be obtained by electrolysis.

In February, 1886, I began to experiment on this plan. The first thing in which I tried to dissolve alumina for electrolysis was fluorspar, but I found that its fusing point was too high. I next made some magnesium fluoride, but found this also to have a rather high fusing point. I then took some cryolite, and found that it melted easily and in the molten condition dissolved alumina in large proportions. I rigged up a little electric battery—mostly borrowed from my professor of chemistry, Professor Jewett, of Oberlin College, where I had graduated the previous summer. I melted some cryolite in a clay crucible and dissolved alumina in it and passed an electric current through the molten mass for about two hours. When I poured out the melted mass I found no aluminum. It then occurred to me that the operation might be interfered with by impurities, principally silica, dissolved from the clay crucible. I next made a carbon crucible, enclosed it in a clay crucible, and repeated the experiment with better success. After passing the current for about two hours I poured out the material and found a number of small globules of aluminum. I was then quite sure that I had discovered the process that I was after.

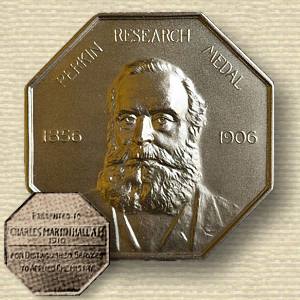

Reverse reads: “Presented to Charles Martin Hall AM 1910 For Distinguished Services to Applied Chemistry.” (source)

I undertook to broaden and improve the method, and found that I could use, instead of cryolite, other double fluorides, particularly a double fluoride of potassium and aluminum. The most important change, however, which I made at this time, was in the material used as an anode. I wanted to get rid of the burning up of the carbon anodes. I tried a platinum anode and found that it seemed to work all right, but it was too expensive. I discovered that if I used a fusible bath of a potassium double fluoride with a sodium double fluoride, I could use a copper anode, which immediately became coated with a thin film of copper oxide and acted like a permanent platinum anode. This was not a step in advance as I had hoped, because more or less copper got into the reduced aluminum, and the use of a copper anode led me to use very fusible baths, which on the whole did not work as well as the less fusible baths. It is probable that this change delayed a successful result for a year or two.

When worked on a small scale, this process with [p.148] any of the baths I have mentioned, and with either copper or carbon anodes, is not apparently promising. The ampere efficiency is low, sometimes zero, and the bath, whether composed of sodium or potassium salt, becomes filled with a black substance which accumulates and renders the process very difficult. I presume that my friend, Dr. Héroult, whom I have the pleasure of seeing here to-night, who invented the process independently in France about the same time, encountered the same difficulties. In spite of the difficulties mentioned, however, I had great faith in the theoretical possibilities of the process, and believed that the practical obstacles could be overcome, so I stuck to it from the start.

On the financial side I had, in the course of three years, three different sets of partners or backers, of whom two sets became discouraged and gave up. In the summer and fall of 1886, I worked with some people in Boston with whom my brother had made some financial arrangement. The results there obtained were not satisfactory to them and in October, 1886, my Boston friends declined to go further.

In December, 1886, I returned to my home in Oberlin, continued my study, and found that a bath composed of a very fusible double fluoride of aluminum and potassium, with copper anodes, worked much better than anything I had before tried. I have here a number of buttons of aluminum made by this method at that time. The larger one was made with current from a galvanic battery on December 7, 1886, and weighs about 8 grams.

After this I negotiated with the head of one of the large chemical manufacturing companies of the United States with headquarters at Cleveland, but we could not finally agree. I thought then, and have thought since, that this gentleman was the kind of man whom the proverbial inventor meets when he is deprived of the fruits of his labor. He was described to me as extremely careful and conservative, and was always wanting to take a few days more to think the matter over. He kept me on the string six months, and the kind of contract which he finally offered seemed to me entirely one-sided. The gentleman told a friend of mine afterwards that I was no business man (which was no doubt true), but I received what seemed to me much fairer treatment from all with whom I afterwards had business dealings, and found much more liberal associates and friends.

The Cowles Electric Smelting & Aluminum Company, who were then making aluminum alloys at Lockport, N. Y., were the second set of people who became interested in my invention. They took an option on it, and I spent a year with them, from July, 1887, to July, 1888. They finally gave up their option. The baths which I used at Lockport worked well for a few days, but after a time became less efficient. I finally worked out a system by which the difficulties were overcome. This was by making a bath consisting partly of calcium fluoride, or fluorspar, and adding 3 or 4 per cent, of calcium chloride, and using carbon anodes. I reasoned that chlorine was evolved and burned up the objectionable compound which spoiled the bath. After finally overcoming the difficulties which I have mentioned, I made several pounds of aluminum in small crucibles, which I showed to Mr. Alfred Cowles and gave him all the facts in relation to the same, but he was not interested.

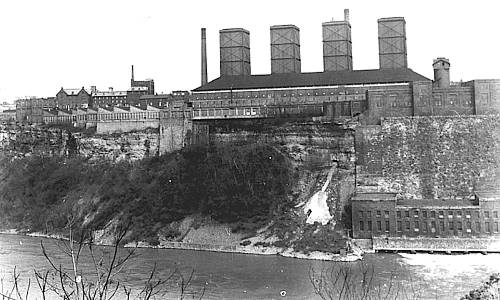

Aluminum rolling mill and pot room buildings. Viewed from Canadian side of the gorge, down river from Niagara Falls. (source)

I then sent a representative—Mr. Romaine Cole, now dead—to Pittsburgh, to get together the gentlemen who formed the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, now the Aluminium Company of America. We started in the summer of 1888 to build and operate a commercial plant on Smallman Street in Pittsburgh. We had at our disposal about fifty horse-power in electrical current of 2,000 amperes. It took a, few weeks after starting to get the dimensions of our baths just right, and then the difficulties which I have referred to disappeared as if by magic. The clogging and spoiling of the bath, which had caused trouble for the last three years, did not occur on a large scale. No calcium chloride was required. It seems that this is a process (unlike a good many others) which works badly on a small scale and well on a large scale. I accounted for this by the fact that on a large scale the electrodes are further separated and there is less circulation between the positive and negative electrodes, which lowers the efficiency and favors the formation of the clogging black compound. We also found, as I had predicted nearly three years before and had stated in a patent application filed two years before, that on a commercial scale no external heat was required to keep our baths in fusion. This was a great advantage, but I believe that it resulted from a law of nature and not from any invention, as we did not use any excess of current for maintaining fusion, but only the normal current and voltage for electrolytic purposes. The use of the electric current for fusing and heating in connection with electrolysis was a thing which had been disclosed and published almost a century before.

The manufacturing of aluminum has now grown to a great commercial business. Many workers have contributed to it, and the credit is to be divided among many. Our financial people, particularly the gentlemen of the Mellon Bank, of Pittsburgh, have given indispensable aid. Our patent attorneys and experts, our engineering and chemical staff, sales-agents, superintendents, foremen and others have all done their share. In the commercial development of the business I think the greatest credit is due to our first President, Captain Alfred E. Hunt, who died in 1899, and to our present President, Mr. Arthur V. Davis, who has been identified with the business for twenty-two years, and who has been manager and general of our forces for the last eleven years.

- Science Quotes by Charles Martin Hall.

- 6 Dec - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Hall's birth.

- Charles Martin Hall, Creator of the Aluminum Age - from The World’s Work (1914).

- Properties of Aluminum - by Charles Hall, from Western Electrician (1891).

- Aluminium History - from Scientific American Supplement (6 Mar 1886)

- Made of Aluminum: A Life of Charles Martin Hall, by Rosamond McPherson Young. - book suggestion.