(source)

(source)

|

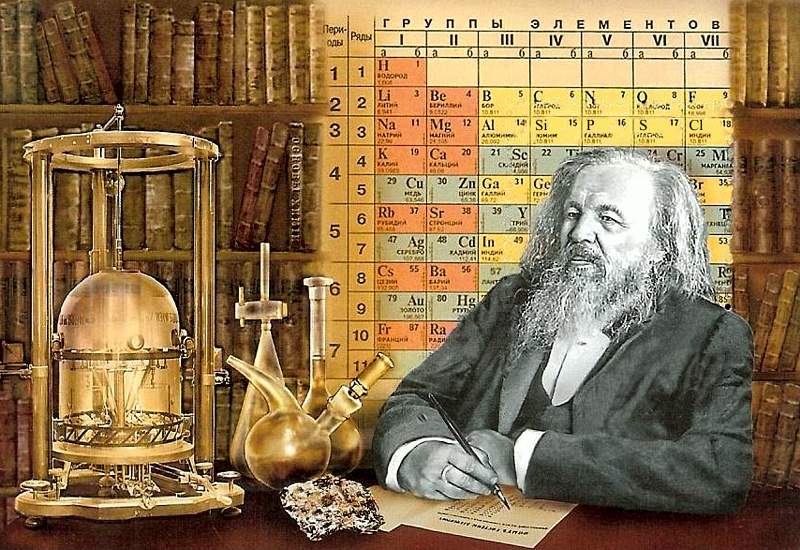

Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev

(8 Feb 1834 - 2 Feb 1907)

Russian chemist who developed the periodic classification of the elements.

|

A Footnote on Science

by Dmitry Mendeleev

from Principles Of Science (1891)

[p.viii] Chemistry, like every other science, is at once a means and an end. It is a means of attaining certain practicable aspirations. Thus, by its assistance, the obtaining of matter in its various forms is facilitated; it shows new possibilities of availing ourselves of the forces of nature, indicates the methods of preparing many substances, points out their properties, etc. In this sense chemistry is closely connected with the work of the manufacturer and the artisan, its sphere is active, and is a means of promoting general welfare.

Besides this honourable vocation, chemistry has another. With it, as with every other elaborated science, there are many lofty aspirations, the contemplation of which serves to inspire its workers and partisans. This contemplation comprises not only the principal data [p.ix] of the science, but also the generally-accepted deductions, and also hypotheses, which refer to phenomena as yet but imperfectly known. In this latter sense scientific contemplation varies much with times and persons, it bears the stamp of creative power, and comprehends the highest branch of scientific progress.

In that pure enjoyment experienced on approaching to the ideal, in that eagerness to draw aside the veil from the hidden truth, and even in that discord which exists between the various workers, we ought to see the surest pledges of further scientific success. Science thus advances, discovering new truths, and at the same time obtaining practical results.

The edifice of science not only requires material but also a plan, and necessitates the work of preparing the materials, putting them together, working out the plans and the symmetrical proportions of the various parts. To conceive, understand, and grasp the whole symmetry of the scientific edifice, including its unfinished portions, is equivalent to tasting that enjoyment only conveyed by the highest forms of beauty and truth. Without the material, the plan alone is but a castle in the air, a mere possibility, whilst the material without a plan is but useless matter; all depends on the concordance of the materials with the plan and execution, and the general harmony thereby attained.

In the work of science, the artisan, architect, and creator are very often one and the same individual, but sometimes, as in other walks of life, there is a difference between them; sometimes the plan is preconceived, sometimes it follows the preparation and accumulation of the raw material. Free access to the edifice of science is not only allowed to those who devised the plan, worked out the detailed drawings, prepared the materials, or piled up the brickwork, but also to all those who are desirous of making a close acquaintance with the plan, and wish to avoid dwelling in the vaults or in the garrets where the useless lumber is stored.

Knowing how contented, free, and joyful is life in the realms of science, one fervently wishes that many would enter their portals. On this account many pages of this treatise are unwittingly stamped with the earnest desire that the habits of chemical contemplation which I have endeavoured to instil into the minds of my readers will incite them to the further study of science. Science will then flourish in them and by them, on a fuller acquaintance not only with that little which is enclosed within the narrow limits of my work, but with the further learning which they must imbibe in order to make themselves masters of our science and partakers in its further advancement.

Those who enlist in the cause of science have no reason to fear when they remember the urgent need for practical workers in the spheres of agriculture, arta, and manufacture. By summoning adherents to the work of theoretical chemistry, I am confident that I call them to a most useful labour, to the habit of dealing correctly with nature and its laws, and to the possibility of becoming truly practical men.

In order to become actual chemists, it is necessary for beginners to be well and closely acquainted with three important branches of chemistry—analytical, organic, and theoretical. That part of chemistry which is dealt with in this treatise is only the groundwork of the edifice. For the learning and development of chemistry in its truest and fullest sense, beginners ought, in the first place, to turn their attention to the practical work of analytical chemistry; in the second place, to practical and theoretical [p.x] acquaintance with some special chemical question, studying the original treatises of the investigators of the subject (at first, under the direction of experienced teachers), because in working out particular facts the faculty of judgment and of correct criticism becomes sharpened; in the third place, to a knowledge of current scientific questions through the special chemical journals and papers, and by intercourse with other chemists.

The time has come to turn aside from visionary contemplation, from platonic aspirations, and from classical verbosity, and to enter the regions of actual labour for the common weal, and to prove that the study of science is not only an excellent education for youth, but that it instils the virtues of labour and truth, and creates solid national wealth, material and mental, which without it would be unattainable. Science, which deals with the infinite, is itself without bounds.

- Science Quotes by Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev.

- 8 Feb - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Mendeleev's birth.

- Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleyev: His Life and His Work, by O. N. Pisarzhevsky. - book suggestion.

- Booklist for Dmitry Mendeleyev.