(source)

(source)

|

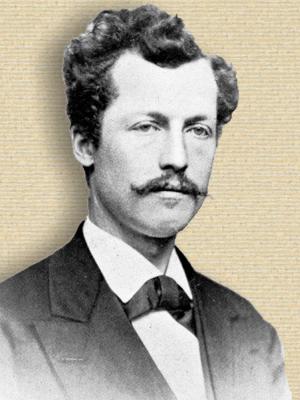

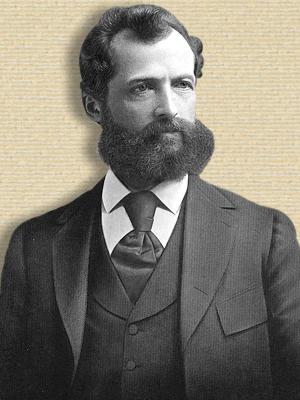

Ottmar Mergenthaler

(11 May 1854 - 28 Oct 1899)

German-American inventor who invented the Linotype machine which revolutionized typesetting, enabling one operator at a keyboard to do the work of three men setting moveable type. The machine cast each line as a bar.

|

THE MAN WHO REVOLUTIONIZED TYPESETTING

OTTMAR MERGENTHALER

from Our Foreign-Born Citizens: What They Have Done for America (1922)

By Annie E. S. Beard

[p.167] IN these days of the multiplicity of the printed page we may well remember the man who invented the linotype which enables an operator to turn out printed matter four or five times faster than it can be done by hand. From Germany came in 1872 the young man who was the inventor of this machine. He was born in May, 1854, at Bietigheim, located some twenty miles from Stuttgart. His father teacher, his mother also belonged to a family which for long years had practiced that profession. The boy was educated in his father’s school, while he had at home work that did not permit much time for play. He helped cook the meals, wash dishes, build fires during the winter and take care of the garden in the summer. The year round he was expected to feed the pigs and cattle.

At the age of fourteen Ottmar was to begin his training as a teacher but that occupation did not offer any attractions for him. He had a special liking [p.168] for mechanics, having kept clocks in repair and made models of animals out of wood. Finally he decided to become an apprentice to a Mr. Hahl, a brother of his stepmother, and a maker of watches and clocks. The terms were four years’ service without wages; the payment of a small premium; provide his own tools, but be furnished board and lodging by his employer. Ottmar had a pleasant home with him, enjoyed his work and the company of the other young men workers. He developed unusual skill and mechanical talent, and succeeded so well that Mr. Hahl paid him wages for a year before the expiration of his apprenticeship. The rarity of the young man’s ability is evident from the fact that this was the first time in a business life of over thirty years that Mr. Hahl had found occasion so to recognize talent in any youth.

Ottmar sought to improve all opportunities open to him in the night school, getting in this way, his first lessons in mechanical drawing which later proved to be of much advantage to him in the drafting of his inventions. In 1872, at the close of his four years’ apprenticeship, he had to decide where to locate for starting in business on his own account. The close of the Franco-Prussian War had left conditions in Germany very unsatisfactory. There was a large amount of unemployment, and increased [p.169] military duties were causing many young men to leave the country. Ottmar therefore decided to do likewise, and applied to August Hahl, a son of his late employer, and a maker of electrical instruments in Washington, D. C., for a loan of passage money to be repaid by working in his factory. The money was promptly sent and Mergenthaler landed in Baltimore in October, 1872, going at once to his destination at Washington.

Electrical instruments were unfamiliar to him, but he soon mastered their workings, and within two years was made foreman of the shop, even acting as business manager when Mr. Hahl was absent. The United States Signal Service had only been established a short time and Mergenthaler’s work was largely the making of standard instruments for it, for which he appeared to have special fitness. Washington was a place where inventor’s models, which were required whenever any one filed an application for a patent, were particularly built, and this brought Mergenthaler into contact with many inventors and naturally stimulated his own talent in that direction. In August, 1876, his attention was attracted to an invention of a writing machine. He examined it and saw how to remedy its defects. He was commissioned to build a machine of full size, which he did in 1877. But though much improved, it never could be a real success. [p.170] Then an attempt was made to have stereotypy take the place of lithography in the making of an impression machine, but after several efforts Mergenthaler told his employers that it could never be brought to perfection.

Finally in January, 1883, J. O. Clephane and others who were interested in backing these various attempts, told Mergenthaler to devise a machine to take the place of typesetting done by hand, which was a slow and laborious process. On New Year’s Day he had dissolved the partnership with Mr. Hahl, which had existed for two years, and started in business for himself. He had been for some time in Baltimore and there he proceeded to work out the desires of his Washington friends. His own plan was to imprint a matrix—a slight bar of metal in which is sunk a character to serve as a mold-line by line, each line being justified as a unit. Experiments were tried, but without success, until one day the thought came into his mind; why not stamp the matrices or molds into type bars and pour fluid metal into them, as is done by typefounders? In this case he desired to do the whole process in one machine.

His backers needed persuasion before they were willing to endorse the new idea, but finally they gave the order to Mergenthaler to build two machines according to his plan. In 1884, when [p.171] the first of these machines was ready to be tested, a dozen spectators came to see the operation. Everything went off well. The line of type was composed by touching a keyboard. Then the fluid metal was poured over it and a finished linotype, shining like silver, dropped from the machine, while each matrix was sent back to its own receptacle. All was done within fifty seconds. It was a notable event in the history of printing

During the next two years the inventor improved and simplified his linotype. In February, 1885, he exhibited a much improved machine at the Chamberlain Hotel in Washington, printers from all over the world being interested. A banquet followed in honor of the inventor’s great achievement. But still later Mergenthaler saw that to make it more perfect he must give visibility to its motions so that the operator should be able to see what he is doing. He also aimed to produce a single-matrix machine. Other inventors were at work on similar ideas, but the invention of Mergenthaler had points of excellence which gave it first place, chief of all being that the three processes of typesetting, typefounding, and stereotyping are combined in one machine. Whitelaw Reid, editor of the New York Tribune, gave the linotype its name. He was the first to use the new machine [p.172] in printing his newspaper. At the close of 1886 a dozen of them were at work in the Tribune offices. The Chicago Inter-Ocean and the Louisville Courier-Journal also adopted it. In 1880 big profits were gained from the linotype. The New York Tribune saved within twelve months $80,000. And yet the inventor’s royalty was only fifty dollars per machine.

Still Mergenthaler continued to make improvements until he had at last a wonderfully perfect machine. As it now stands, its method of working, briefly told, is as follows: The operator has before him the control of about 1500 matrices. Each matrix or mold is a small flat plate of brass which has on its outer edge an incised letter, and on its upper end a series of teeth for distributing purposes. As the operator touches a key the letter desired is set free and glides in full view to its assembling place, which supplants the old-fashioned stick. In like manner each letter reaches its destination until the word is completed. Then the operator touches a key that inserts a space shaped like a double wedge. When the line of type is full, it is justified by moving a lever, and it is carried automatically to a mold where liquid metal is forced against the matrices and spaces. Then the line of type is ready to be printed. This slug, as it is called, in a moment [p.173] is hard and cool enough to pass to a tray where other slugs are swiftly added to form a page or column ready for the printing press. A set of matrices often replaces a font of type weighing two hundred times as much. A section of the machine returns the matrices to their boxes as quickly as 270 a minute, and unerringly, unless a matrix is bent by accident or otherwise injured. In a linotype three distinct operations go on together: composing one line, casting a second and distributing a third, so that the machine has a pace exceeding that at which an expert operator can finger his keys.

Since Mergenthaler’s work was finished, his linotype has been adapted to composing books of the most exacting kind, mathematical treatises, and the like. It has also been arranged for printing in many languages, and for casting letters twice the ordinary length for use in newspaper headings.

Mergenthaler was beloved by all the men who worked for him. He was good to all of them and no matter how humble their station, he always had a kind word for them and a friendly word to say of them.

When worn out at last with hard work, tuberculosis developed in 1894 and five years later he passed away, but not before he had been gladdened [p.174] by recognition of his great ability by the award of a medal from the Cooper Institute of New York; the John Scott medal by the City of Philadelphia; and the Elliott Cresson gold medal by the Franklin Institute of Philadephia.

- Science Quotes by Ottmar Mergenthaler.

- 11 May - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Mergenthaler's birth.

- The Linotype - Manufacturer and Builder Magazine Article (Jun 1889) - Frontispiece

- Full article on 'The Linotype' - Manufacturer and Builder Magazine (Jun 1889)

- Mergenthaler’s Speech - after exhibiting his Linotype invention in Washington D.C. (1885).

- Today in Science History short event description for first Linotype machine put in service on 1 Jul 1886.

- The Biography of Ottmar Mergenthaler, Inventor of the Linotype, by Carl Schlesinger (ed.). - book suggestion.