(source)

(source)

|

Édouard Michelin

(23 Jun 1859 - 25 Aug 1940)

French industrialist who, with his older brother André, founded Michelin Tyre Co. in 1888. They made the first pneumatic tyres that could easily be removed and replaced. Also, they introduced tread patterns, low-pressure balloon tyres and steel-cord tyres.

|

EDOUARD MICHELIN

Who tries to give his customers what they want before they know they want it.

by H.M. Davidson

from System: The Magazine of Business (1922)

“To tell a man how best to use tires, and to make him want them, is far better than trying to tell him that your tire is best. If you believe that yours is, let your customer find out,” says Edouard Michelin.

[p.412] ECONOMIC laws are sluggish but inexorable. Keeping always a step ahead of economic laws, out of harm’s way; never admitting that you are defeated; never fearing what is new and untried—these are the secrets of successful large-scale factory management, according to Edouard Michelin, said to be the most American of French manufacturers, who with his brother André has guided the fortunes of Michelin and Company, makers of pneumatic tires, from somewhere just below the danger line to its present position of solidity and world renown.

“In every phase of business life, keep at least one year ahead of the other fellow.” Edouard Michelin phrased it thus himself, succinctly, in perfect English, yes, in perfect American, for his accent is devoid of the usual British cast one finds in English-speaking Frenchmen. His speech is one tart, crisp sentence after another, full of Americanisms.

In his little office at Clermont-Ferrand, Michelin has fought battles and made history in the tire industry. He is neither a large man, nor imposing, in the [p.413] sense in which one finds men of 63 years who have been executives nearly all their lives. Rather, he has the half-timid look of the scientist, disturbed at research, or of the artist whose pre-vision has been interrupted.

The heartiness of his handshake and the decisiveness with which he plunges toward a subject, once introduced, tends to belie this first impression. But when one learns that 10 years of his young manhood had been spent studying art under Bouguereau, one begins to understand him better.

There was a crisis, when Michelin was 28, in the affairs of his grandfather’s rubber factory. He was compelled to abandon painting and join his brother André in the seemingly hopeless task of building up a mismanaged business.

“No man can serve two masters,” said Edouard, and threw away his brushes. He has never touched them since.

There is more than one road to self-expression, however. Instead of painting canvases, the artist went in wholeheartedly for rubber tire making. Even today Michelin is known in his factory as a whirring wheel of energy, but in those earlier years he concentrated furiously on the one burning desire—to make the best rubber tire possible. He is still concentrating, and moving always in only one direction.

“In fulfilling the wants of the public,” Michelin declares, “a manufacturer should keep as far ahead as his imagination and his knowledge of his buying public will let him. One should never wait to see what it is a customer is going to want. Give him, rather, what he needs, before he has sensed that need himself.”

And he tells, in point, the story of the development of the pneumatic tire in his own factory.

“We were making bicycle tires when I started in business and things were in bad shape. There were 52 men in our organization and all of us were discouraged. Perhaps I was discouraged the most—but I didn’t dare show it.”

One day, a bicycle with a punctured tire was brought to Michelin for repairs.

“The first pneumatics we had ever seen were on that bicycle,” narrates Michelin. “They were glued to the wheels! And it took four hours to mend the puncture—two to plug up the hole, two to glue back the tire!

“I went for a ride on the wheel, and in 15 minutes I had another puncture. But I was convinced that the future of tires lay in the pneumatic and from that day to this I have never stopped experimenting with them.”

At this juncture Michelin displayed some of that uncanny pre-vision which is one of his biggest business assets. He sized up his buyer. “We must make a tire that is easily changeable,” he foresaw, “not by a mechanician, but by anybody— even by an imbecile.” And he goes on to tell: “Some time after, we put on the market a demountable pneumatic tire. How it was laughed at! But it won the Paris to Brest bicycle race, and then there was less laughter. We were just two years ahead of our customers that time.

“I say two years because it was after that period of time that I went before the directors of the company and announced, to their astonishment, a 5% dividend.

“‘Gentlemen,’ I said to them, ‘That dividend could be larger. The balance we are going to use in the manufacture of a pneumatic tire for motor cars!’“

And the Michelins did just that, although competing contemporaries thought them crazy. Some of these competitors are out of business, while the Michelin factory employs 20,000 persons and covers an area as large as the remainder of Clermont-Ferrand—which itself is no inconsiderable city.

Throughout the following years the Michelins kept ahead. Working together, the two brothers entered upon more than one interesting side-track from their product. They encouraged motoring of all sorts, were the first to give prizes for the development of aviation, but never once did they deviate from their single idea—to make the best tire in the world.

“You can’t serve two masters,” Edouard insisted and stuck to it.

But it is not only in regard to the product he manufactures that the manager of a large factory must keep ahead. The same principle applies, Michelin will assure you, in the handling of labor as well. “We have never failed,” he explains, “to announce a raise in wages months ahead of other companies. In like manner, we announce a cut. Wages follow prices; that is economic law. But the wise employer beats economic law to it. As a result of our policy we have never had a serious strike.”

MICHELIN’S RELATIONS WITH HIS EMPLOYEES

Michelin likes to tell how he “beat to it” the need for social legislation by the establishment of workmen’s bonuses, of inexpensive dwellings for workmen and of his individual pet hobby, a free medicohygienic department to care for and advise not only the men employed in the factory, but also their wives and children.

“When there were only 500 employees in the Michelin works, I knew everyone personally,” as he tells it. “They used to come to see me in my office, and tell me their troubles. A couple of years later when there were nearly 2,000, I found they did not all look me in the eyes in the same spirit of comradeship. Some of them—well I found I actually did not know their names!

“So I had to give them help as a group, instead of as individuals. They have appreciated my efforts, and I am proud of the spirit that has resulted.”

In advertising, too, the Michelins turned over virgin soil, [p.446] and proved the truth of Edouard's maxims. Back in 1900, few firms in France had any conception of large-scale advertising. Even today, many detest and fear it.

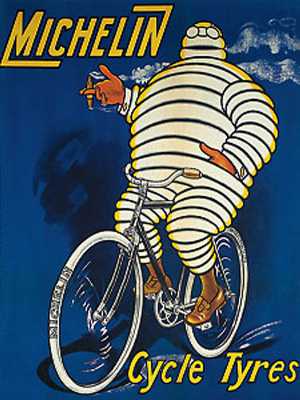

That year, the Michelins exhibited at the Lyons exhibition a pile of tires of all sizes, arranged in order of size, so that the pile tapered towards a point at the top. To Edouard Michelin, artist, the likeness to a man was as immediately apparent as it was comic.

“All it needed was arms,” said Michelin, “for, being a Frenchman, it wanted to speak!”

Arms were soon supplied, and a head as well, and there was Bibendum, the tire man! Since 1900, more than 20,000 Bibendums, doing every conceivable thing to help the motorist, in every imaginable attitude and position, have greeted the world from signpost and magazine page. Everyone in France knows Bibendum. It was one of the most successful advertising devices in history.

“If I advertised, it would ruin me,” a well-known French silk merchant near Lyons had told me only a few days before I saw Michelin. I repeated the remark. Michelin, exponent of the principle of “getting the jump” on the other fellow, smiled knowingly under his beard.

“If you advertise to tell lies, it will ruin you,” he retorted, “but if you advertise to tell the public the truth, and particularly to give information, it will bring you success.

“I learned early that to tell a man how best to use tires, and to make him want them, was far better than trying to tell him that your tire is the best in the world. If you believe that yours is, let your customer find it out.

“Our best advertising stroke, I believe, has been the publication of maps and guides. On these we make no profit whatever, although a slight margin is made by the retailer. We started out by giving away these articles, and it was the wrong principle. The day I found a Michelin guide book used to prop up a wobbly table, we put a price on them. Now there is tremendous demand.

It was about a dozen years ago that Michelin foresaw that the coming market for an article produced in quantity for popular consumption was a world market rather than a national one. Then it was that the Michelins established their branch in America. Not only has it been a financial success, but through it the Michelins are kept in intimate touch with the newest American ideas in tire manufacture.

“We need these ideas in France,” confesses Michelin. “If I had my way every French boy would be required to take a trip to America as part of his education.” But how Michelin got his American ideas without making any such trip is really the amazing thing!

- Science Quotes by Édouard Michelin.

- 23 Jun - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Michelin's birth.

- The Michelin Men: Driving an Empire, by Herbert Lottman. - book suggestion.