(source)

(source)

|

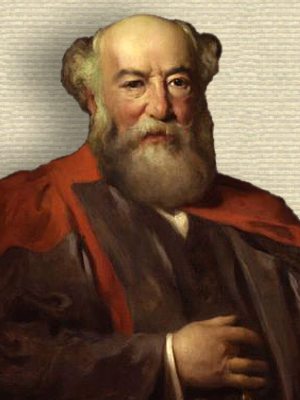

Ludwig Mond

(7 Mar 1839 - 11 Dec 1909)

German-British chemist and industrialist whose varied contributions to the chemical industry include perfecting a method of soda manufacture, a process for the extraction of nickel, and coining (with Charles Langer) the term “fuel cell” while attempting to generate electricity by reacting hydrogen with oxygen.

|

The Late Dr. Ludwig Mond.

from Obituary in Metallurgical and Chemical Engineering (1910)

Dr. Ludwig Mond, who died in London before the sun rose on Saturday, December 11, was one of the most successful industrial chemists of his time—a man who owed his success to a rare combination of business ability, capacity for research and energy. The public knew him as one of the founders of the alkali firm of Messrs. Brunner, Mond & Company, as the inventor of the Mond gas and of a nickel process, and as a generous donor to many scientific institutions. We take this account of his life from the London Engineering.

Ludwig Mond was born nearly 71 years ago at Cassel, then the capital of the Electorate of Hessen, which since 1866 has formed part of the Prussian kingdom. His father, a merchant, had him trained at the Polytechnic Institute of Cassel, and later at the universities of Marburg and Heidelberg. Recommendations from so distinguished professors as Hermann Kolbe and Robert Bunsen stood young Mond in good stead when, after having held appointments in two German chemical works, he came to England in 1862. He found employment at Widnes in the chemical works of Messrs. Hutchinson and Earle, and there he was able to show that a method patented by him for recovering the sulphur, which had so far been wasted, in the black ash of the Leblanc process was technically applicable; this method was adopted in Newcastle and Glasgow.

Returning to the Continent, he joined Ernest Solvay, of Charleroi, near Brussels, the inventor of the ammonia-soda process. Having founded Solvay works at Utrecht, he returned to England in 1867, acquired the Solvay patents for England and started, in 1872, works of his own at Winnington, near Northwich, over the Cheshire salt deposits, with Mr. (now Sir) John Brunner, whose acquaintance he had made in the Hutchinson family, as partner.

It was a risky undertaking to compete in England against the Leblanc process, where it had been elaborated into one of the most perfect cyclic processes known. The raw materials of the Leblanc process are salt, sulphuric acid, coal and lime—all relatively cheap. In the ammonia-soda process the brine is saturated with ammonia—an expensive material—and then with carbonic acid, the crystallizing bicarbonate of soda being afterwards converted, by boiling or by calcination, into ordinary carbonate of soda. The Leblanc process yields hydrochloric acid as a by-product; in the Solvay process the chlorine combines with calcium to form chloride of calcium, and the enormous quantities of this compound remain practically waste heaps up to the present time. A good deal of the success of the new firm was due to the improvements which they effected in the recovery of the ammonia (by means of quicklime). When they started they knew that Dyar and Hemming had tried an ammonia-soda process, likewise in Cheshire in 1838, and had failed, and that the struggle against the giant Leblanc was considered hopeless. After 1875, however, their success was assured. In recent years new and formidable rivals have arisen in the electrolytic alkali processes. To meet that rivalry new efforts were made to utilize the calcium chloride; some of it is now treated with zinc oxide and transformed into zinc chloride, which on electrolysis yields a very pure zinc, and the calcium chloride in itself makes a fair road dressing.

The sight of the enormous waste of gases in his Winnington boilers, it is said, suggested to Dr. Mond the study of the producer-gas problem. He succeeded in burning cheap bituminous slack by the aid of an air-blast and steam and in absorbing the ammonia evolved by dilute sulphuric acid, thus obtaining a fair producer gas and, in addition, ammonium sulphate as a by-product, whose value, unfortunately, decreased, owing to this and other new sources of production. Mond gas is now chiefly made at Dudley Port, in Staffordshire.

The same researches led him to another discovery. The producer gas contains hydrogen, and when, 20 and more years ago, the problem of galvanic gas cells for the direct generation of electricity from coal—not by way of boilers, steam engines and dynamos—excited general attention, Dr. Mond attempted to isolate the hydrogen from the other constituents of the producer gas. For this purpose he conducted the gas over various compounds and metals, and observed that nickel was taken up by the gas; it was the carbon monoxide which formed nickel carbonyl under certain conditions of temperature and pressure, and this carbonyl is again decomposed at 200° C. and deposits a mirror of pure metal. The new compound was first described by Dr. Mond in 1890, and the Mond Nickel Works at Clydach, near Swansea, are now converting part of the nickel ores from the famous Canadian mine at Sudbury, or the matter smelted there, into a very pure nickel.

Years were, of course, required to work out this process, and Dr. Mond had the assistance of many able chemists and engineers in his researches and undertakings. It would be wrong, however, to regard Dr. Mond mainly as the managing director and commercial chief. Dr. Mond was himself a remarkably capable and painstaking research chemist. During the last five years his health caused his friends much anxiety. About a year ago he recovered wonderfully, and he ought to have spared himself. Always busy and hard at work with the general management, however, he took the study of the carbonyls up again, and succeeded in preparing carbonyls of iron, cobalt, molybdenum and ruthenium, which are stable only at very high pressures—450 atmospheres in the last-mentioned case. He announced these discoveries at the International Chemical Congress, which met in London in May and June last. When he fell ill again this autumn grave fears were entertained.

Since 1857 Dr. Mond has been domiciled in England. The year previous he married his cousin, Miss Frieda Loewenthal. His winters he liked to spend in Italy, and his house, the Poplars, in Avenue Road, near Regent's Park, in which he died, is well stocked with masterpieces of the early Italian school. His friendship with the great Italian chemist, Stanislao Cannizzaro, induced him to found a Cannizzaro prize.

Having long supported low-temperature research in the Royal Institution of London, at whose lectures he was a familiar figure, he established the Davy-Faraday Research Laboratory in the house adjoining the Royal Institution in Albemarle Street, and endowed it liberally. The laboratory was opened by the King in 1896. His donations to the Universities of London, Cambridge, Manchester and Liverpool, the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, and the association which aims at creating a Chemische Reichsanstalt, a sister institute to the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt in [p.88] Charlottenburg, were on a grand scale; and it was due to his munificence that the Royal Society, which elected him a Fellow in 1901, was enabled to start its international catalogue of scientific papers. Dr. Mond held honorary degrees from the Universities of Padua, Heidelberg, Manchester and Oxford. One of the honors he valued most highly was his election, in 1898, to the Athenaeum Club under the rule which empowers the Council to admit distinguished men of science.

Dr. Mond leaves two sons—Dr. Robert Mond, a Cambridge scientist, and Arthur M. Mond, M. P. for Chester...

By Dr. Mond's will he leaves $300,000, payable free of legacy duty, on the death of his wife, to the Royal Society of London. The income from this bequest is to be devoted to the assistance of research in the natural sciences along various lines. A like sum for like purposes is also bequeathed to the University of Heidelberg.

In addition to other bequests, Dr. Mond left a fund in the care of six trustees to be chosen by the directors of Brunner, Mond and Company, three trustees to be taken from among the workmen of that firm. The income of the fund is to be used to assist or pension aged or disabled employees of the company. In the event of the dissolution of the company the money will go to the poor of Northwich, where the chief works are located. Another $100,000 is also bequeathed to the city of Cassel, Germany, for charitable purposes. The will then disposes of the collection which Dr. Mond had got together with the advice of Dr. Richter. The collection, which is not large in point of number, was formed slowly, Dr. Mond hardly ever buying more than two or three pictures a year since he made his first acquisition, in 1892.

A schedule annexed to the will gives the names of fifty-six pictures, the list being headed “Pictures for the National Gallery.” On the death of Mrs. Mond the trustees of the National Gallery may select at least three-fourths of the works named in this list, or may make up the number, forty-two, from his remaining works of art. These pictures are to be kept together in a room or rooms in the National Gallery under the name of the Mond Collection. He leaves his wife power to bequeath not more than twelve of his pictures to any person she may think fit, but they may not be taken from those selected by the National Gallery.

All the remainder of the pictures are to be given, either singly or in lots, to museums or institutions in Europe or Canada, each one to be marked as the gift of Dr. Mond, but without any restriction as to their being kept together unless at least forty go to one institution. Dr. Mond hoped that the proper authorities will consider the pictures given to the National Gallery as of national interest, and remit all duties that might be levied on the bequest.

- Science Quotes by Ludwig Mond.

- 7 Mar - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Mond's birth.

- Ludwig Mond Biography (2) - from Obituary in Engineering And Mining Journal (1910).

- The Life of Ludwig Mond, by J. M Cohen. - book suggestion.