(source)

(source)

|

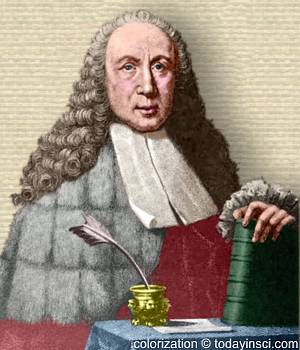

Giovanni Battista Morgagni

(25 Feb 1682 - 5 Dec 1771)

Italian anatomist and pathologist who laid the foundations of pathological anatomy as an exact science.

|

Giovanni Battista Morgani

Heroes of Medicine

From The Practitioner (1896)

[p. 161] Giovanni Battista Morgagni was born at Forli, in the Romagna, on February 25th, 1682, of a “noble,” or what in this country would be called an upper middle class, family. He lost his father when he was about seven years old, but his mother was a woman of great intelligence, and he was very carefully educated not only in the classical languages, but in science. He was soon recognised to be a boy of exceptional gifts, and already, at the age of fourteen, we find him admitted a member of an “academy” in his native town, where he read verses of his own composition and took his part in debating philosophical questions. At the ago of sixteen he began the study of medicine in the University of Bologna, where in 1701 he took his Doctor's degree in philosophy as well as in medicine, according to the custom of the time. Among his teachers at Bologna the one who chiefly influenced him was Valsalva, whose name he always cites in his writings with particular veneration. Morgagni assisted Valsalva in his great work, De Aure Humanâ, which was published in 1704, and took his place in the lecture-room for a whole year, during which the professor was absent from Bologna.

Morgagni did not confine his studies to medicine, but took all learning to be his province. Anatomy, however, was from the first his chosen field of work. In 1706 he published his first work, Adversaria Anatomica Prima, which contains several new discoveries in anatomy and corrections of many errors of previous writers. After a further period of study at Venice and afterwards at Padua, he practised his profession for a time at his native place. In 1711 the Professorship of Theoretical Medicine at Padua was offered to him, and three years later he was appointed to the Chair of Anatomy. He [p.162] had already won for himself a leading place among the anatomists of Europe, and he was recognised as a not unworthy successor of such former occupants of the Chair as Vesalius, Falloppius, Fabricius ab Acquapendente, and Casserius.

Morgagni's life was entirely given up to his work, and was so uneventful that the biographer finds little to record except the dates of publication of his various works, the academic dignities conferred on him, the distinctions showered upon him by learned bodies throughout Europe, including our own Royal Society, the visits which he received from emperors and kings, and the praises which he received from men of light and leading, from Popes downwards. His native town placed a marble bust of him in its Council Hall during his lifetime (in 1763), with an inscription describing him as “primus in humani corporis historid.” More practical evidence of appreciation was given by the University of Padua, which raised his stipend from 500 to 1,000, and afterwards to 2,000 florins a year, an altogether exceptional stretch of liberality.

Morgagni held his professorship for sixty years, and continued to work with almost unabated vigour till the end came suddenly on December 5th, 1771, when he was close on ninety. At the time of his death he was revising his works with a view to the publication of a complete edition.

It is impossible here to enumerate the writings that came from Morgagni's pen, which was never idle during the seventy years that elapsed between his taking his degree and the coming of the night wherein no man can work. He wrote on archaeology, history, geography, philology, and points of minute scholarship, as well as on medical subjects. He could discuss such matters as the death of Cleopatra with a learning worthy of a better cause, and could set grammatical and literary critics right in their interpretation of classical writers.

![Giovanni Battista Morgagni quote: Those who have dissected or inspected many [bodies]](https://todayinsci.com/M/Morgagni_Giovanni/MorgagniGiovanni-Dissection300px.jpg)

Pathologic Anatomy - History of Medicine series

Artist: Robert Alan Thom (1961) (source)

This learned trifling was, however, only an intellectual relaxation for Morgagni. His work lay in unfolding the mysteries of organic structure, and especially in interpreting the handwriting of disease in the different parts of the human body. He was the Columbus of an intellectual country previously unexplored, though it had been visited by a stray [p.163] traveller or two of the Marco Polo kind, with an eye rather for marvels than for sober fact. His great work, De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis, saw the light at Venice in 1761, when he was in his eightieth year. In this work Morgagni laid the foundations of pathological anatomy. He not only described the changes from the normal condition found in the body after death from diseases of various kinds, but traced the connection between the lesions and the symptoms observed during life. This had hardly been attempted before, and the work will stand through the ages as a conspicuous landmark in the history of medicine. Morgagni did not, like Moses, die in sight of the promised land to which he had guided his people, but took possession of it. He enlarged the realm of medicine by the wealth of new facts which he added to the sum of knowledge, almost as much as by his conquest of a new and immensely rich province of research.

In person Morgagni was tall, with ruddy complexion, fair hair, and blue eyes, which retained their keenness of vision to the very end of his long life. He himself attributed his independence of spectacles to his habit of bathing his eyes every morning in cold water. His constitution was of iron, and he could work with the regularity and persistence of a machine. As for his character, it is difficult to discern the real man through the cloud of encomiastic but somewhat vague superlatives in which his figure has been wrapped by those who have written about him. It was his good fortune that the work which lay nearest his hand throughout his life was just that for which he was best fitted by taste as well as by talent, and his robust health enabled him to do it with his might. His life seems to have flowed on in an unbroken stream of ever-broadening success and prosperity. His mode of life was simple, and his household continued to be managed on a frugal scale even when he had become comparatively wealthy. Morgagni, indeed, has been taxed with avarice, and the strange unanimity shown by his twelve daughters in becoming nuns rather suggests that their father may have found this a cheap way of disposing of them. On the other hand, he for many years contributed to the support of a poor man who had saved him from [p.164] drowning in childhood. All Morgagni's eulogists speak of his extraordinary memory, and this lifelong remembrance of an obligation may be cited as a more remarkable proof of it than his passing examinations and defending theses with profuse erudition when ophthalmia prevented his having recourse to books.

In all his portraits a certain priggishness of expression is noticeable. This may perhaps be due partly to the wig “volumed and vast and rolling far” down his shoulders. He was a man of even temper, but touchy on the point of dignity, and he was mightily offended because someone quoted his name without prefixing “Illustrissimus” thereto. He was occasionally bitter in controversy, but men of science are rather given to the free use of uncomplimentary terms about those who differ from them.

Morgagni was a sincerely religious man, but it is rather startling to find that he was a believer in judicial astrology. His wife, whom he married in 1712, died long before him. She brought him fifteen children, only three of whom were sons. Of these sons, two died before him. The elder was a youth of the greatest promise, and his death was a lasting sorrow to his father.

On the whole, however, Morgagni's life must have been a singularly happy one. He had no passion but the desire for knowledge, and that he was able to satisfy to the full in his own way. Few men can have gone down to the grave with a more assured sense that they had done the work that was given them to do, and few have a better title to a place among the immortals.

- Science Quotes by Giovanni Battista Morgagni.

- 25 Feb - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Morgagni's birth.

- Doctors: The Biography of Medicine, by Sherwin B. Nuland. - book suggestion.

![Giovanni Battista Morgagni quote: Those who have dissected or inspected many [bodies] have at least learnt to doubt; while other](https://todayinsci.com/M/Morgagni_Giovanni/MorgagniGiovanni-DoubtThm.jpg)