(source)

(source)

|

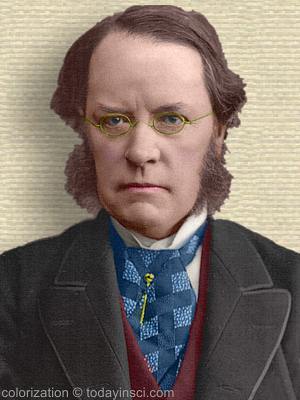

Lyon Playfair

(21 May 1818 - 29 May 1898)

Scottish chemist who studied medicine then turned to chemistry under Justus von Liebig. He became a professor of chemistry, but expanded his career to being a government scientist, promoting science education and urging industry to take up scientific advances.

|

Address on the recollections of the state of chemistry at the time of the foundation of the Chemical Society.

CHEMICAL SOCIETY’S JUBILEE

by Sir Lyon Playfair

from Nature (1891)

[p.491] It is a sad feeling that there are now living among us only five of the original founders of the Chemical Society. I am one of those five, and have therefore been selected to address a few words to you to-day.

You have learned from the excellent discourse of our President that before 1841 chemistry was being both rapidly developed and rapidly evolved. New methods of research were being created; organic chemistry had almost been created. There were many luminaries in the chemical firmament all over the world at that time, and if I mention a few names they will appear to many of you as milestones representing mere discoveries and progress, though they are names well known to the older members of the Society and the few founders who are left as strong personalities with whom we connect much kindness, hospitality, and encouragement.

Liebig was then facile princeps chemist of the world. He formed a school, and showed how to advance chemistry by original research. At that time, in 1841, the year of our foundation, his brilliant pupil Hofmann had scarcely risen above the horizon. Kopp and Bunsen had made researches, but were still young. There were in Germany names of the highest importance in our science: at Gottingen there was Wöhler, the dear friend of Liebig, and associated with him in his work; in Berlin there was Mitscherlich, the aristocrat of chemistry; there was Rose, the most lovable of our fraternity, who had raised analysis to a high platform by improving methods of research; there was Dove, the jolliest of companions, who had joined physics to chemistry; and lastly, there was Rammelsberg, who took mineralogy out of the domain of physics, and made it part of the domain of chemistry.

In France, at that time—I speak only of those whom I personally knew, and whose friendship has ever been valuable to me—there was a man who died only the other day, but who was a veteran then, and famous for his researches on the fatty bodies, Chevreul; there was Balard, the discoverer of bromine; there was [p.492] Baron Thenard, the king among lecturers; there was Dumas the eloquent, who established the doctrine of substitutions; and there were other good workers who had not yet acquired the reputations which they afterwards gained —men like Pelouze, Fremy, and Regnault.

These were the great luminaries on the Continent; but whom had we at home?

There was my old teacher, and to all old chemists devoted friend, Graham, who founded one of the first laboratories of research which existed in this country; who by his profound philosophical views did so much to promote the advancement of chemistry. There was, at Manchester, Dalton, who did as much for chemistry as Kepler did for astronomy. There was Faraday, that prince of electricians; and my dear friend Grove, who now sits beside me, who formulated the correlation of forces; and Joule, who discovered the mechanical equivalent of heat.

These names show that the great science of chemistry was active in our country. But it required association to bring the chemists together; it required association to encourage young men in research, and to give them that support which united science always adds to the promotion of investigation.

Fifty years, gentlemen, is a long time in the history of an individual, but it is a mere mathematical point in the history of a science. We are sometimes told that chemistry is a modern science: that is not true. The moment that men’s minds began to experiment on the constitution of matter, there was a science of chemistry.

Tubal Cain was a chemist because he was skilled in brass and iron. Thales was a chemist when he declared that everything was made of water. Anaximines was equally a chemist when he said that everything was made of air. Aristotle was a very advanced chemist when he got out four elements—fire, air, earth, and water. So chemistry has progressed from those days to the present time by the investigation of the laws which govern the combination of the elements, and by examining into the constitution of matter.

Now, chemists and microscopists have often been taunted with the fact that they are content to rely on those small particles of matter which we call atoms, and that they are narrow as men of science compared with astronomers, who sweep the skies and examine the motions of large masses of matter. But the astronomers have been obliged to take us into partnership. We have helped them to know the constitution of the stars, and we are now helping them to discover how new worlds are formed.

It is unnecessary for me to detain you longer upon the subject of the progress of chemistry; for that has been ably done by the President. But I would like to hold out some encouragement with regard to the future of chemistry. There are periods of great activity in the progress of every science, and that has been manifested during the period terminating in our jubilee.

When this Society meets to celebrate its centenary, what a different chemistry it is likely to be from the chemistry of to-day! Already analysis has led to synthesis, yet we know very little with regard to the processes that go on in organic bodies.

With regard to the elements, we are beginning to doubt what they are, and even to hope for their resolution. When we find such an important law as the one that the properties of the elements are periodic functions of their atomic weights, what a field is thrown open for investigation! It is a field of discovery the borders of which we have scarcely yet crossed. The motions of the elements may ultimately be known to us, and even the ultimate elements themselves. We call them elements still, because they have a certain fixity, and we are at present unable to decompose them.

But recollect that sometimes there comes a man who changes the whole features of a science. What did Newton do for astronomy? With one fell swoop he cleared away the vortices of Descartes, and the tremendous system of “monads,” “sufficient reason,” and “pre-established harmony” of Leibnitz, by his philosophy; and we may hope that during the next fifty years there will arise a chemical Newton, who will enable us to know far more than we now know, who may bring under one general law the motions of atoms, and even the rupture of those which we now call elements simply because they have acquired a fixity in the order of things and are able to resist changes in the struggle for existence.

Let us have hope in the future. Veterans like myself and my friend Grove will not live to see these great discoveries, but some of our younger men will participate in the chemistry of the future, and will look back with interest to the chemistry of the fifty years we are now celebrating. There is no heart here so cold as to doubt the rapid and continuous progress of our science. I express my own thought, and I believe that I express the conviction of each person present, when I conclude in the words of Tennyson :—

Still moving after truth long sought,

Will learn new things when I am not.

Thou hast not gained a real height,

Nor art thou nearer to the light,

Because the scale is infinite.”

- Science Quotes by Lyon Playfair.

- 21 May - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Playfair's birth.