(source)

(source)

|

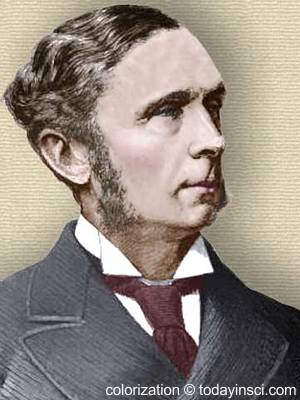

Sir Morell Mackenzie

(7 Jul 1837 - 3 Feb 1892)

English laryngologist whose career as Britain’s leading specialist was overshadowed by controversy over his treatment of the laryngeal cancer of his patient, German Emperor Frederick III.

|

Whistler’s Poodle

A humorous tale, by a person unknown, remains in circulation today, although the story had its origin in the early 1900s. It has been widely repeated through the decades since. The name of Sir Morell Mackenzie was involved in the fiction because at that time he was a prominent physician. But the target of the joke was another London resident, the well-known controversial artist, James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). One telling goes like this:

❝James Whistler, the Victorian artist, showed scant respect for the hierarchy of any profession. When his poodle fell ill with a throat infection, he sent immediately for the country’s leading ear, nose, and throat specialist, Sir Morell Mackenzie. The great man was not amused when he was shown his patient, but he conducted a thorough examination, wrote out a prescription, and left with his fee.

The next day Whistler received a message asking him to call on Mackenzie without delay. Fearing some development in the poodle’s condition, Whistler hurried to the doctor’s house.

‘So good of you to come, Mr. Whistler,’ said Mackenzie as his visitor was shown in. ‘I wanted to see you about having my front door painted.’❞

The context is even more interesting. In 1890, James Whistler published his book, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, because he never took criticism of his paintings lying down. As a character trait, he always wanted his to be the vituperative last word. The book has been called “a classic in the literature of insult and denigration.” Whistler was already renowned for letters to newspapers chronicling his many petty grievances against various people in his orbit. Whisler’s deadly sarcasm and stinging remarks may be regarded by some as witty, or by others as whining and obnoxious. Regardless, he reveled in his notoriety. That the now legendary story emerged as a put-down aimed at Whistler was well understand by the Victorian public of his time.

The article below, reproduced from The Medical Record (4 Jan 1913), fills out the background of the narrative.

The Growth of a Legend

“X” relates that he “has recently been watching, with much interest, the circulation through the weekly papers, of a story anent the artist Whistler and Sir Morell Mackenzie, which, curiously enough, starting in Paris, has now reached the American medical Journals and seems embarked on a long and active career.

Briefly, it is this:— Whistler’s pet poodle being very ill, Sir Morell Mackenzie was sent for in hot haste. Indignant at having been summoned to see a dog, he, nevertheless, pocketed his dignity, and prescribed, secundum artem. Whistler, having thanked the ‘eminent surgeon’ profusely, begged to know the fee. Sir Morell, turning away, said pleasantly, ‘Oh! My house wants painting. Will you see to it?’

Now Sir Morell Mackenzie was, without doubt, an accomplished laryngologist; but why Whistler—whose brother,* by-the-bye, was almost equally celebrated in the same department of medicine—should have desired the services of a laryngoloist for his poodle, heaven only knows. Mr. Ben Trovato†, the eminent raconteur, seems for the moment at fault.

Still, the natural history of such legends as this leads us to suppose that the story of the laryngologist and the poodle will continue to circulate, till after having served its day it ‘falls on sleep,’ later to be revived by the journalists of the next generation about some heroes of to-day.

“Many years ago there was related in that excellent, even if mid-Victorian periodical, The Leisure Hour, a similar story; but this time concerning Nélaton and Meisonnier. Some time during the early days of the Second Empire, Nélaton was ur gently summoned to the painter’s villa in the banlieue de Paris. After some time had been spent in the way of sumptuous entertainment. Nélaton, a little impatiently, begged to be introduced to the sufferer. Whereupon two gorgeous flunkeys entered the room bearing on a cushion a little dog with a broken limb, and the master fell on his knees entreating the surgeon’s forgiveness and aid. Nélaton addressed himself to the case, and set the limb; he was departing, when Meisonnier desired to know, as Portia would have said, how he might gratify the gentleman, for, in his mind, he was much bound to him. The story goes that Nélaton then declared the door of his ‘cabinet de cotisultation’ to need painting, and hoped that the artist would restore it. Meisonnier seized the occasion, we are told, of the surgeon’s temporary absence from Paris, to produce, on each panel, a veritable tour de force.

“Now this is a more exquisite tale than the other. But the germ of both may be traced in the episode of Radcliffe and Kneller, as related by the veracious Pittis. Radcliffe and Kneller lived near each other in Bow street; their gardens were separated by a wall. Radcliffe, for the better entertainment of his friends, begged the privilege of entrance to Kneller’s plaisaunce, through a door which he desired to make in the wall. The painter, with accustomed grace, gave his assent, but, the privilege being abused by the doctor’s servants, had thereafter courteously to hint that if the grievance recurred, the door must be bricked up. Whereupon the choleric doctor sent a message to say that Sir Godfrey might do what he liked to the door, so long as he did not paint it. ‘Did my very good friend, Dr. Radcliffe, say so?’ cried Sir Godfrey. ‘Go back to him and after presenting my service to him, tell him that I can take anything from him but his physic!”—The Universal Medical Record.

† Ben Trovato is not to be read as an actual person. It is a humorous construct from the Italian phrase, “se non è vero, è ben trovato”. Of an anecdote, the phrase means “even if it is not true, it is plausible,” or “…a happy invention,” or “…well conceived.” The literal translation of the Italian words “ben trovato” is “well found”. —Webmaster.

- Science Quotes by Sir Morell Mackenzie.

- 7 Jul - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Mackenzie's birth.

- Dr. Morell Mackenzie, laryngologist - Biography from Scientific American (1887).