(source)

(source)

|

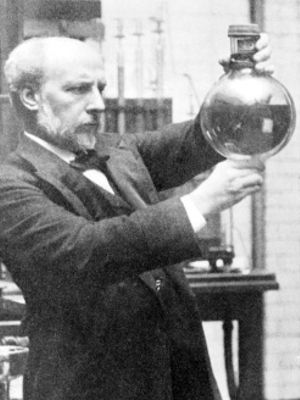

Sir James Dewar

(20 Sep 1842 - 27 Mar 1923)

Scottish chemist and physicist whose research with materials at low-temperature led him to devise the Dewar vacuum-insulated double-walled flask, now familiar as the thermos bottle. He also was a co-inventor of cordite smokeless explosive powder.

|

Sir James Dewar, F.R.S.

Famous for his Researches in Low Temperature Phenomena

By P. F. Mottelay

from Scientific American (1910)

SIR JAMES DEWAR was born at Kincardine-on-Forth, Scotland, on the 20th of September, 1842, received his education at Dollar Academy and Edinburgh University, and when twenty-nine years of age was married to Helen Rose, daughter of William Banks, Edinburgh.

He had in 1863 been appointed assistant to Sir Lyon Playfair, then professor of chemistry at Edinburgh University, from whom he received the principal part of his chemical training, and in 1868 spent the summer term at the University of Ghent under the celebrated professor Friedrich August Kekulé, continuing a research started at Edinburgh on the oxidation of the coal-tar bases, from which originated the Dewar-Körner theory of the pyridine ring. He is the author of numerous papers covering an unusually wide range of chemical and physical subjects, and is now entitled, among other claims, to the distinction of being the recognized world authority on the constitution of the atmosphere. In 1875 he was appointed Jacksonian Professor of Natural Experimental Philosophy in the University of Cambridge, and he has occupied since 1877 the highly coveted post of Fullerian Professor of Chemistry in the Royal Institution. He has besides been lecturer on chemistry at the Dick Veterinary College, chemist to the Highland and Agricultural Society, as well as examiner in the universities of Edinburgh and London, and is at present director of the Davy-Faraday Research Laboratory.

The field of work with which Dewar's name is perhaps more closely linked than any other is that of low temperature research. During the year 1891, on the occasion of the celebration of the centenary of Faraday's birth, he proved among other facts, in a singularly interesting lecture at the Royal Institution, that oxygen, which is known to be but feebly magnetic at ordinary temperatures, becomes highly susceptible to magnetism when subjected to minus 180 deg. C. He had previously lectured notably on the “Liquefaction of Oxygen,” on the “Chemical Actions of Liquid Oxygen,” and on the “Production of Oxygen in the Solid State,” and these papers were rapidly followed by others, among which should be singled out those on the “Spectrum of Liquid Oxygen,” on “Liquid Atmospheric Air,” on “Liquid Nitrogen,” on the “Electrical Resistance and Thermo-Electric Powers of Pure Metals, Alloys, and Non-Metals at the Boiling Point of Oxygen and of Liquid Air,” on “Electric and Magnetic Researches at Low Temperatures,” and on the “Properties of Liquid Fluorine.” In the production of the last-mentioned liquid he worked in conjunction with Prof. H. Moissan.

It was for his investigations of the properties of matter at lowest temperatures that the Rumford medal was presented to him in 1894 by the Royal society, whose president at the time remarked that Prof. Dewar had displayed throughout his researches not only marvelous skill and fertility of resource, but also great personal courage, and that he had not alone succeeded in preparing large quantities of liquid oxygen. but that he had, by his device of vacuum-jacketed vessels, been able to store the liquid under atmospheric pressure during long intervals, and thus to use it as a cooling agent. During his last Friday evening lecture of the 1906 season, Sir James Dewar explained how, with the aid of charcoal, he had been able to make these vacuum-jacketed vessels out of light metals, like copper, nickel, brass, etc., instead of the brittle glass hitherto employed. It is now known that without these peculiar vessels (called Dewar flasks by the scientific world) the crowning achievement of obtaining hydrogen in the liquid state would scarcely have been possible.

In his presidential address to the British Association at Belfast in 1902, Prof. Dewar makes the following reference to the liquefaction of hydrogen, next to helium, the most elusive of all gases; “Compared with an equal volume of liquid air, it requires only one-fifth the quantity of heat for vaporization; on the other hand, its specific heat is ten times that of liquid air or five times that of water. ... It is by far the lightest liquid known, its density being only one-quarter that of water. ... It is by far the coldest liquid known. ... Reduction of the pressure by an air pump brings down the temperature to minus 258 deg., when the liquid becomes a solid resembling frozen foam, and this by further exhaustion is cooled to minus 260 deg., or 13 deg. absolute, which is the lowest steady temperature that has ever been reached. At this nadir of temperature, air becomes a, rigid inert solid. Such cold involves the solidification of every gaseous substance but one (helium) that is at present known to the chemist. As we approach the zero point of absolute temperature, we seem to be nearing what I can only call the death of matter. ... Its existence has long been indicated by the regularly diminishing volumes of gases and the gradual falling off in the resistance offered by pure metals to the passage through them of electricity under increasing degrees of cold. ... The liquefaction of oxygen and air was achieved through the use of liquid ethylene as a cooling agent, which enabled a temperature of minus 140 deg. to be maintained by its steady evaporation in vacuo. Liquid oxygen is markedly magnetic, comparing with iron in this respect in about the ratio of 1 to 1,000. It is a nonconductor of electricity, and an induction coil which would give a long spark in the air, failed to pierce a layer of liquid oxygen one-tenth of a millimeter thick.”

The remarks made at the Belfast meeting would now, of course, have to be modified by reason of the progress since made with helium, as shown in Sir James's papers (1907), “Studies in High Vacua and Helium at Low Temperatures” and (1909) “Problems of Helium and Radium.” In the first-named, he incidentally explained the very slow process of obtaining helium from gas given off by the King's Well at Bath, and alluded to the fact that, in consequence of losing the entire two years' accumulation through the collapse of the glass vacuum vessel containing the regenerator coil, he had to begin all his experiments anew. Notwithstanding this, his researches, though as yet necessarily incomplete, were such as to justify him in predicting the probable properties of liquid helium. Of these, the most important was that the liquid density would be found about 0.14, or at least twice that of liquid hydrogen. Since then this prediction has been closely verified by Prof. Kamerlingh Onnes of Leyden, who has found 0.15 as the experimental value. Sir William Ramsay and Mr. M. W. Travers had inferred with less truth that the liquid density of helium would be 0.43. The critical pressure and general order of constants were what Sir James Dewar suggested, the boiling point being 4 deg. absolute, and the critical point not more than 5 deg. on the absolute scale. The results of direct observations made by Prof. Onnes were: Boiling point, 4½ deg; critical temperature, 5½ deg. C. absolute; critical pressure, 2½ atmospheres.

One of Dewar’s most important discoveries in other fields was that of cordite, made in conjunction with Sir Frederick Abel, who also aided him in developing other explosives accepted by the English government for military purposes. Mention should be made of the fact that he was first to study the very important oxidation products of the quinoline bases, and that much of his attention has likewise been given to the interesting study of phosphorescence.

In the accompanying photograph Sir James Dewar is shown holding in his hands a bulb of the type associated with his name. He is of middle height and well built. His strong, clear-cut, refined features and deep-set eyes give him an impressive appearance. Whether seen at the experimental table, on the speaker's platform, or in his magnificent quarters at the Royal Institution, the impression he conveys is one of great earnestness, happily combining the thoughtfulness of the born scientist with the dignity and refinement attaching to his prominent associations and very attractive home surroundings. A strongly individual stamp is given to these latter by a wealth of the very rarest pictures, engravings, Benvenuto carvings, tapestries, scarce books bound in the most sumptuous fashion, etc., which he and Lady Dewar have collected in the course of their travels.

Sir James Dewar's delivery in public is most excellent, and a certain charm is added to his well-modulated voice by a touch of the Scotch accent which he still retains. The preparation of his lectures and reports shows great care and precise method. Indeed, were it not for this, and his propensity for a happy co-ordination of facts, figures, and deductions, the forceful, logical, convincing presentation with which he always appears to impress his hearers, would be impossible. As can be easily realized, it is not an easy task, when treating of the very abstruse subjects he has dealt with, to adapt to the comprehension of the masses the results of explorations made in hitherto unknown paths such as we have called to attention.

His success has been so marked, so extraordinary, of such benefit to mankind, that we must all wish many more days may be spared him to enhance, as he surely will, the admirable work he has already accomplished, leading him to disclose many more of the valuable secrets that Nature guards so jealously.

- Science Quotes by Sir James Dewar.

- 20 Sep - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of Dewar's birth.

- James Dewar - Solid Air Experiment from The Manufacturer and Builder (1893).

- Air: Scientific Discoveries and Inventions - from Haydn's Dictionary of Dates (1904).

- Air: Scientific Discoveries and Inventions - from Haydn's Dictionary of Dates (1904).

- The Dangers in Radium - from Hygienic Gazette (1910)