(source)

(source)

|

Robert Ernest House

(3 Aug 1875 - 15 Jul 1930)

American physician who championed the use of scopolamine hydrobromide in criminology, which became known as a “truth serum.”

|

The Use Of Scopolamine In Criminology

by Robert E. House, M. D. Ferris, Texas

Article read at the Section on State Medicine and Public Hygiene of the State Medical Association of Texas at El Paso (11 May 1922).

In presenting my technique for the use of scopolamine in criminology, I do not desire to pose as a criminologist.

There are lawyers who maintain that my idea is not constitutional, while others affirm that if it is permissible for a state to take life, liberty and property because of crime, it can be made legal to obtain information from a suspected criminal by the use of a drug. If the use of bloodhounds is legal, the use of scopolamine can be made legal. Although a dog’s trail may lead to the door of a suspect, corroborative evidence is required for conviction. Likewise, all data secured by the use of scopolamine would have to be corroborated. But the legal points involved do not concern me. They are matters for the Legislature and the courts to determine. We belong to a generation of universal education. Crime must be controlled by intelligence.

The suppression of crime is not entirely a legal question. It is a problem for the physician, the economist and the lawyer. We, as physicians, should encourage the criminologist by lending to him the surgeon, the internist and all of the rest of the resources of medicine, just as we have done in the case of the flea man, the fly man, the mosquito man, the bed-bug man and all the other ologists.

I ask the question, by what process of reasoning should the State of Texas be more concerned in the conviction of the guilty than in the acquittal of the innocent? The following letter from an inmate of a Texas penitentiary may be of interest in this connection:

“Upon notice of the test of twilight serum upon Scrivener, in your custody, wish to say I am very much interested. I am serving a long prison sentence for murder of a man in Travis County, Texas, in 1915. There was no evidence against me, only I was a poor Mexican. I would certainly be glad if I could be a subject of this serum, and if it be in your power, would you please forward this letter to the proper authorities? I ask for a test upon my innocence, sir, that I may be eliminated from charges as a result. Trust you will give this your due consideration. I will thank you in advance for the time used and the favor rendered.”

One-third of the arrests made are shown by statistics to be in error, and not all convictions are warranted by the facts in the case.

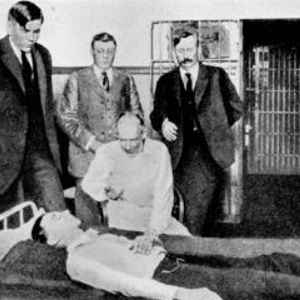

The first investigation, so far as I can learn, of the use of scopolamine in criminology, and its first test, was in the Dallas County jail, February 13, 1922. The test was conducted under the personal supervision of Dr. W. M. Hale, Dallas County Health Officer.1 The test was made possible by the agreement of District Attorney Maury Hughes. My experience with this drug was obtained while House Surgeon for the Parkland Hospital, in Dallas, during the years 1897 and 1898. There, all of the city's pauper cocaine and morphine addicts were treated by the Florence-Rosser hyoscine method.

I have demonstrated the function of scopolamine upon which its use in criminology depends, in over four hundred cases of obstetrics, but I have made only the two tests referred to, upon alleged criminals. Legal inhibitions have made it impossible to carry the record any further. In both tests my subjects were able to prove by corroboration that their convictions for certain crimes were in error. In one case, a very intelligent white man by the name of Scrivener was the subject of the experiment, and in the other a negro of average intelligence was used.

Scrivener was given first ¼ grain of morphine and 1/100 grain of scopolamine. In twenty minutes he was given 1/200 grain of scopolamine. In thirty minutes he was lightly anaesthetized with chloroform and allowed to rest thirty minutes, when 1/400 grain of scopolamine was administered. In twenty minutes he failed to respond to the memory test. To insure safety and save giving more scopolamine he was anaesthetized with chloroform to complete unconsciousness, and engaged in conversation at the earliest possible moment.

The set of questions to be asked were not known to Scrivener. Mr. Hughes, the District Attorney, stated that if I would obtain correct answers to them he would be satisfied. They were as follows:

(1) Q-—What is your age? A.—27. (Correct.)

(2) Q.—Where were you born? A.—Laredo. (Correct. )

(3) Q.—Did you rob Guy's Pharmacy? A.—No. I was picked up for it the night of the Sanger Bros, robbery, but I do not know where Guy's Pharmacy is.

(This answer lost me support. He was sent to the penitentiary for fifteen years for this crime, hence it was believed that he lied and that the test was not reliable. I will try to show that he told the truth.)

(4) Q.—Who robbed the Hondo Bank? In reply he named five men, two of whom are now in the penitentiary for that offense, two are in Mexico and one is at large. This question was valuable because of the fact that he would never before answer it, maintaining that he was only invited to participate.

(5) Q.—What are you reading in jail? A.—Mechanical books, about automobiles. (Correct.)

(6) Q.—Who gave you the books? A.—Mrs. Holt. (Correct.)

(7) Q.—Where did she live? A.—Austin. (Correct.)

(8) Q.—Is she dead or alive? A.—Dead. She died last November. (Correct.)

It is a matter of court record that two officers testified that Scrivener was in their custody in Fort Worth the night of the robbery and dismissed him a few minutes after eleven o'clock. The drug store was held up at eleven thirty. I suspect the jury might have felt, as did the prosecuting attorney, that it was possible for the officers to be mistaken in their dates. The following letter is of interest in this connection:

“I have noticed with some interest your experiments with the so-called Truth Serum on prisoners in the Dallas County jail, and I was especially impressed with the results in the case of W. S. Scrivener, in which he denied that he was guilty of the robbery in connection with the Guy's Pharmacy, for which offense he was sentenced to a term in the penitentiary. I was District Attorney of Dallas County at the time this offense was committed, and I prosecuted Scrivener for what was known as the Sanger Bros, robbery, as well as for the robbery of Guy's Pharmacy. His conviction in the case was predicated exclusively upon his identification by one of the clerks. He contended at the time, and there were some witnesses there who testified to his contention, that he was at the time that offense was committed, in Fort Worth and not in Dallas. I had no doubt then of his guilt, but after his conviction he told me that his conviction in the Sanger Bros, matter was a just one, but he was not guilty of the robbery of Guy's Pharmacy. He went to the penitentiary and was afterwards paroled. He violated his parole and escaped, and was again arrested in connection with what was known as the Jackson Street Post Office Robbery, and was convicted in the Federal Court for that offense. I was defending one of his co-defendants in the Post Office robbery matter, and afterwards talked with Scrivener again, and he assured me he was innocent of the Guy's Pharmacy robbery. Having in mind that it would serve no purpose for him to deny the robbery at this time, in view of the fact that Governor had pardoned him for both of these offenses, in order to permit him to testify against both of his co-defendants in the Post Office robbery case, for my own satisfaction I began an investigation of the Guy’s Pharmacy matter, and became convinced and am now of the opinion, that Scrivener was in Fort Worth at the time that offense was committed, and was not here and did not participate in that offense. I am sure he was identified as a result of having been arrested for an offense similar to the Guy’s Pharmacy robbery, which occurred about the same time, that is, within a few days of the Sanger Bros, robbery. I am writing you this to aid you, if it will, in reaching your conclusion in your experiments.”

The morning following the experiment, I went to see Scrivener and a negro who had been subjected to the same test at the same time, to see how many memory islands each had retained. I asked Scrivener to write me a description of his experience. I desired to compare his letter with the conversations I had held with my obstetrical patients. Scrivener’s letter follows:

“In compliance with your request, to describe my experience, I wish to express my opinion, also. I am unable to remember all that occurred during the experiment, but speaking from the facts that I have knowledge of, it is my firm belief that scopolamine can be used in an effectual way. It was through curiosity to determine the possible strength of resistance that caused me to try and remember what did occur, but after the second administration of chloroform my imagination seemed to be paralyzed, and only at short intervals was I conscious of my surroundings, and during these times I remember being asked two questions. The first was, ‘Who robbed the Hondo Bank?’ At the same time this question was asked, it seemed some one asked me, ‘Did I meet anyone in San Antonio,’ and the names must have been intended for that question, although I do not remember giving any names until they were repeated to me by a newspaper reporter. The other question was, ‘Who robbed Guy’s Pharmacy?’

I remember the question, but at the same time I was unconscious of how I answered or all that I said. After I had regained consciousness I began to realize that at times during the experiment I had a desire to answer any question that I could hear, and it seemed that when a question was asked my mind would center upon the true facts of the answer and I would speak voluntarily, without any strength of will to manufacture an answer. Well, doctor, I have not suffered any ill effects from the experiment, and I feel grateful that I had the opportunity to be of some useful service. Knowing you will be successful in using scopolamine to great advantage, I am.”

This letter shows a mass of irrelevant ideas. There is no relationship between his letter and the actual routine of the case. It deals with his mind going under the influence of the drug and to his coming out. The San Antonio question was asked by someone while I was questioning the negro, before I placed Scrivener under chloroform the second time. The part of the letter about his mind centering on questions referred also to incidents happening before I placed him under chloroform the second time. Scrivener would answer the negro’s questions as if I were presenting them to him. I asked the negro how long he stayed in New York. Scrivener spoke out and said, “I never was in New York.” While Scrivener was across the room, he could hear because he was in a condition of semi-narcosis.

The negro had no memory islands. He went to sleep after the second administration of scopolamine and slept from 3:00 p.m. until 8:00 p.m. The negro answered every question. Mr. Hughes was never able to obtain a contradiction to the first story given, and he stated that the negro made a better witness under the drug than he did when sober. This negro had been sentenced to a term of fifteen years in the penitentiary. The evidence thus obtained enabled his lawyer to prove a case of mistaken identity.

Scopolamine will depress the cerebrum to such a degree as to destroy the power of reasoning. Events stored in the cerebrum as memory can be obtained by direct stimulation of the centers of hearing.

My attention was first attracted to this peculiar phenomenon September 7, 1916, while conducting a case of labor under the influence of scopolamine. We desired to weigh the baby, and inquired for the scales. The husband stated that he could not find them. The wife, apparently sound asleep, spoke up and said, ‘They are in the kitchen on a nail behind the picture.” The fact that this woman suffered no pain and did not remember when her child was delivered, yet could answer correctly a question she had overheard, appealed to me so strongly that I decided to ascertain if that in reality were another function of scopolamine. In a confinement case you find your dosage by engaging the patient in conversation, to note the memory test. Hence my investigation was a simple matter. I observed that, without exception, the patient always replied with the truth. The uniqueness of the results obtained from a large number of cases examined was sufficient to prove to me that I could make anyone tell the truth on any question.

There is positively no harm in the drug if the laws governing its action are understood. Scopolamine depresses the cerebrum and interrupts the connection between the cerebral cortex and the spinal cord. In old age, the cortical cells of the cerebrum are inhibited in their functions because the dendrites, with their synapses, shrink. The cortical cells do not then readily transmit thought to their neighboring thought cells, to complete what is called memory. That is why old people apparently live in the past and do not remember recent events with ease. A similar condition will be found in the brain of a person under the influence of scopolamine, except that instead of shrinkage of the synapses there is a temporary contraction.

Scarcely any two patients are alike, or require the same amount of medicine. I am not always sure that I can differentiate correctly the conversation due to scopolamine from the conversation of normalcy. In my first twilight case, my patient sat up in bed with tears streaming down her face, screaming, “I am dying, I tell you, I am dying. You said you were going to ease me and that stuff has not eased me at all.” Her husband believed her and began to cry. Had I not had previous experience with the drug, there would have been three people in a mighty bad fix. The next day the patient laughed and said she did not remember talking in that manner. Four years later, a patient said, “Dr. House (excessively polite), if you will give me a little more medicine I believe I will get easy. So far I cannot feel any influence at all. I am sure it will ease me because all the women say it eases them. I am so anxious for you to be successful in my case.” I believed her and gave her another 1/400 grain of scopolamine. The next day she said she remembered nothing of the conversation at all, nor of my giving her another dose. These two cases should demonstrate that success in handling scopolamine in obstetrics or criminology, will depend upon experience and individuality.

A characteristic of scopolamine is that patients under its influence will awaken of themselves for brief intervals, and retain what they observe. What they do remember is called by Dr. Gauss, memory islands (meaning, I presume, in the sea of unconsciousness). For that reason I advise that in a criminal study the eyes be covered. Under the influence of the drug there is no imagination. They cannot create a lie, because they have no power to think or reason, any more than if under the influence of gas, chloroform or ether.

The criminal test requires, in my opinion, a condition of analgesia. This is not the state in which to conduct an investigation, but it guarantees a depressed cerebrum to start with. The patient gradually comes from under the influence of the drug and reaches the stage of hypalgesia. As the patient progresses further towards consciousness the cerebrum begins to function, and this state of mind is called amnesia, the last stage before consciousness is restored. The patient should be engaged in conversation just the moment there is intelligence enough to understand the question.

The cerebrum is that part of the brain which receives sensation and sends out motor impulses. The nerve cells behind the fissure of Rolando form the area of intelligence. There is no center of speech and no center of memory, but the cells of all the five senses are connected by short cut passages, making a symbolic mechanism for the integration of the sensori-memorial images.

The seat of reciprocal innervation is at the synapses, hence impulses can only travel by contact. A nerve will carry only one impulse at a time, and it transmits the strongest first. Were it not for this function and that mechanism, scopolamine criminology would be valueless. My investigation revealed that scopolamine will violate the Bell-Magundi law of conduction. The “receptive stage” is the moment the reflex arc is established.

The precentral region contains the cells of highest thought, yet the cells of hearing make the cells of the other four senses subservient.

The successful use of scopolamine in criminology is based on the fact that a feeble stimulus is capable of setting in operation nerve impulses that are as potent as those produced by strong stimulants, just as a small percussion cap can set in motion the potential energy of a ton of dynamite. The stimulus of a question can only go to the hearing cells. In pursuance of their functions, the answer is automatically sent back, because the power of reason is inhibited more than the power of hearing. This stage of the mind I was unable to find a name for or a description of, so I have named it “House's Receptive Stage.” It is that condition of the mind found midway between hypalgesia and amnesia.

In the stage of amnesia some patients talk at random. This condition is not for use in criminology. They will talk in hypalgesia following questions propounded in a loud voice, but the association centers do not function sufficiently to return sensible answers. Every “Keeley” man understands the receptive stage. Several of them have told me that they had observed but never appreciated its value in this connection.

In conclusion, the following advice is offered to any who may conclude to test this matter:

Fresh tablets of the levo-rotatory variety should be procured direct from the manufacturer. Old tablets or poor tablets produce the therapeutic effects of atropin.

If the patient is asleep it is necessary to talk in a loud voice, but if the patient is awake, a low tone should be employed to avoid inducing a state of excitement.

Questions to which the answers are known should first be used; if the patient cannot understand, the question should be repeated every ten minutes, but a different one used each time. Impressions made under scopolamine are likely to be remembered while the effects of the drug persist, to be forgotten when the effects of the medicine pass away.

Chloroform, by investigations in Europe and America, has been shown to act in a physiological manner similar to scopolamine. This fact has been utilized in all of my work. The small amount required for this purpose is harmless. In this work, scopolamine and chloroform should be made equal partners. Each drug performs work the other cannot do, the same as morphine and atropine. Ether will not do the work of chloroform.

I have not made the exaggerated claims which have been credited to me by the lay press. I cannot progress further in this work, nor do I care to, unless the medical profession deems the effort worth while.

Dr. Jno. S. Turner, of Dallas: I have had no experience with this drug in this connection. I was not in Dallas at the time the experiments related by the author were made, but I have heard some discussion of them.

There is little known of the action of scopolamine, insofar as it affects the brain centers, and anything said about it at this time would be largely speculative. There may be great possibilities along the line of its use in criminology—its further administration and physiological observation will be necessary to determine that fact. If it meets the expectation of Dr. House, it will be a great adjunct to medico-legal practice, and will be the means of determining justice in many now obscure cases.

I understand from the author of the paper, that his experience has demonstrated that a great deal depends upon the method of administration. Each case must be treated in its individual capacity, in order to get proper results, as individuals respond differently to the action of the drug.

This question is of such importance as to justify further investigation. It is not only important to the medical and legal professions, but to the people at large and to the courts of this country.

Dr. D. Y. Willbern, Runge: I do not know enough of scopolamine from a criminal standpoint, or of its effect upon the centers of the brain, hearing, memory, etc., to discuss the paper intelligently, but would like to relate the following:

On one occasion in my life I lost consciousness. It was while I was in school. I had been vaccinated for smallpox, and had fever. I was sitting up, while my room-mate straightened the bed clothing. Upon arising to return to bed, I fell face forward upon it. I do not know whether I was unconscious for a second, two seconds, or five minutes, but very distinctly I could hear him talking to me. It was four or five minutes, I know, before I was able to move or speak. The important thing in this connection is that I heard him talk before I could answer.

- Science Quotes by Robert Ernest House.

- 3 Aug - short biography, births, deaths and events on date of House's birth.

- 'Truth Serum' Involves Five in Axe Murders, Birmingham, Ala. - reported in New York Times (8 Jan 1924).

- 'Truth Serum' Test Proves Its Power - reported in New York Times (22 Oct 1924).