|

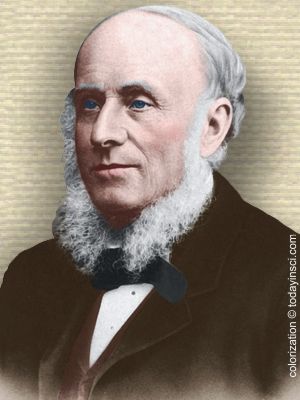

Alexander Bain

(11 Jun 1818 - 18 Sep 1903)

Scottish philosopher and psychologist who wrote a book on Logic and founded the first journal of psychology, Mind. Bain helped establish the application of the scientific method in the field of psychology. He has been credited with writing the first “comprehensive treatise having psychology as its sole purpose.”

|

Science Quotes by Alexander Bain (11 quotes)

Disinterestedness is as great a puzzle and paradox as ever. Indeed, strictly speaking, it is a species of irrationality, or insanity, as regards the individual’s self; a contradiction of the most essential nature of a sentient being, which is to move to pleasure and from pain.

— Alexander Bain

In On the Study of Character: Including an Estimate of Phrenology (1861), 202.

He that could teach mathematics well, would not be a bad teacher in any of [physics, chemistry, biology or psychology] unless by the accident of total inaptitude for experimental illustration; while the mere experimentalist is likely to fall into the error of missing the essential condition of science as reasoned truth; not to speak of the danger of making the instruction an affair of sensation, glitter, or pyrotechnic show.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 298.

Instinct is defined as the untaught ability to perform actions of all kinds, and more especially such as are necessary or useful to the animal.

— Alexander Bain

The Senses and the Intellect (1855, 1974), p. 246.

It is our previous knowledge that must forge the links of connexion between what is given and what is required.

— Alexander Bain

In Induction (1870), 422. Paraphrased by John Tindell when quoting Bain as: “Your present knowledge must forge the links of connection between what has been already achieved and what is now required.” in Fragments of Science for Unscientific People: A Series of Detached Essays (1874), 129.

Mathematics, including not merely Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, and the higher Calculus, but also the applied Mathematics of Natural Philosophy, has a marked and peculiar method or character; it is by preeminence deductive or demonstrative, and exhibits in a

nearly perfect form all the machinery belonging to this mode of obtaining truth. Laying down a very small number of first principles, either self-evident or requiring very little effort to prove them, it evolves a vast number of deductive truths and applications, by a procedure in the highest degree mathematical and systematic.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 148.

Of Science generally we can remark, first, that it is the most perfect embodiment of Truth, and of the ways of getting at Truth. More than anything else does it impress the mind with the nature of Evidence, with the labour and precautions necessary to prove a thing. It is the grand corrective of the laxness of the natural man in receiving unaccredited facts and conclusions. It exemplifies the devices for establishing a fact, or a law, under every variety of circumstances; it saps the credit of everything that is affirmed without being properly attested.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 147-148.

The arguments for the two substances [mind and body] have, we believe, entirely lost their validity; they are no longer compatible with ascertained science and clear thinking. The one substance with two sets of properties, two sides, the physical and the mental—a double-faced unity—would appear to comply with all the exigencies of the case. … The mind is destined to be a double study—to conjoin the mental philosopher with the physical philosopher.

— Alexander Bain

From concluding paragraph in Mind and Body: The Theories of their Relation (1872), 195.

The method of arithmetical teaching is perhaps the best understood of any of the methods concerned with elementary studies.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 288.

The uncertainty where to look for the next opening of discovery brings the pain of conflict and the debility of indecision.

— Alexander Bain

In Appendix, 'Art of Discovery', Logic: Deduction (1870), Vol. 2, 422.

Those that can readily master the difficulties of Mathematics find a considerable charm in the study, sometimes amounting to fascination. This is far from universal; but the subject contains elements of strong interest of a kind that constitutes the pleasures of knowledge. The marvellous devices for solving problems elate the mind with the feeling of intellectual power; and the innumerable constructions of the science leave us lost in wonder.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 153.

What renders a problem definite, and what leaves it indefinite, may best be understood from mathematics. The very important idea of solving a problem within limits of error is an element of rational culture, coming from the same source. The art of totalizing fluctuations by curves is capable of being carried, in conception, far beyond the mathematical domain, where it is first learnt. The distinction between laws and co-efficients applies in every department of causation. The theory of Probable Evidence is the mathematical contribution to Logic, and is of paramount importance.

— Alexander Bain

In Education as a Science (1879), 151-152.

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --

In science it often happens that scientists say, 'You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,' and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

(1987) --